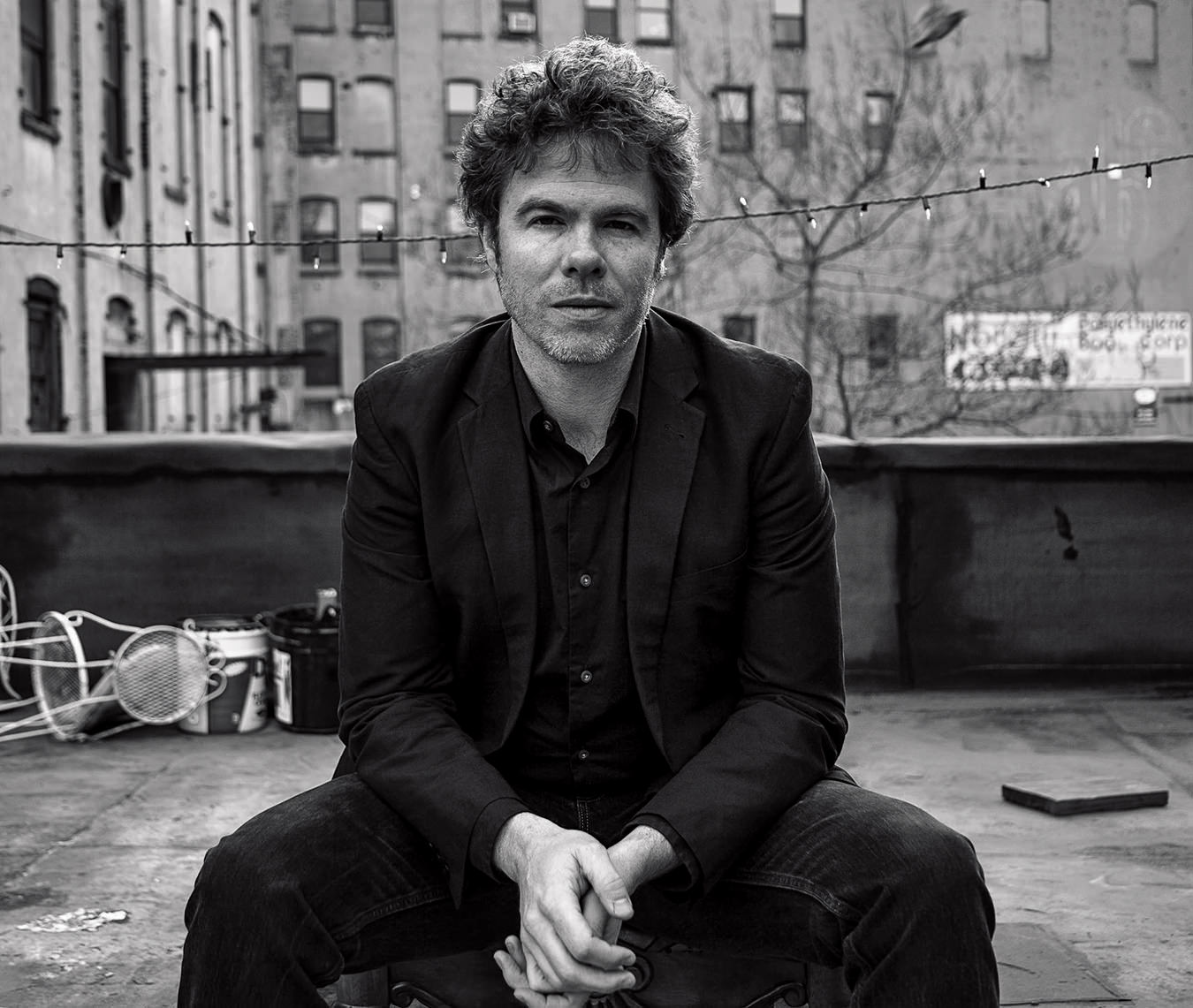

Serena Ryder

Balancing act.

The idea of utopia has become synonymous with paradise: an imagined glowing, smooth-running, conflict-free way of life. For Serena Ryder, the concept is about to become concrete, and perhaps a little more complex. The 33-year-old Millbrook, Ontario, native has named her fifth studio album after this state of existence. Utopia, due for release this fall, follows up on Ryder’s immensely popular Harmony, released in 2012. Three years in the making, Utopia is not as blissful as the title might imply—or even as Ryder first imagined.

“I started making the album in a really bright, bright place in my life,” the singer explains. “And then it got really fucking dark…I was writing from this place where I wasn’t even feeling anything. I was on medication and I couldn’t feel any feelings, or, like 50 per cent of my feelings,” she says. Ryder has spoken candidly about her struggle with depression in the past. With Utopia, she draws from both extremes.

Ryder created a symbol for the album: a triangle, with a black, a white, and a grey side. “[The symbol] is based on the [aboriginal] story of the two wolves,” she says, diving into the parable: an elder tells a grandchild that within everyone there transpires a battle between a light wolf and a dark wolf, good vs. evil. When the grandchild asks which wolf wins, the elder responds, “The one you feed.”

Ryder does not shy away from pain nor does she strive for euphoria.

Ryder’s interpretation of the Cherokee fable—first told to her years ago by long-time friend Simon Wilcox—informed Utopia: “The record is based on feeding both wolves and making them grey.” Wilcox was a key writing partner for Ryder—one of many (others include Meghan Kabir, producer Thomas “Tawgs” Salter, and Jerrod Bettis). “I’ve written with a bunch of different friends on this album—it’s exciting,” she says. “I’ve written with people I feel really comfortable with.”

Writing alongside trusted partners has yielded a diverse repertoire on Utopia; the album shines with Ryder’s willingness to explore every avenue of her journey. “There are three very defined varieties of songs on this record,” she explains. “Four of them are very dark and stripped back; four of them are exciting and full and bright; four of them are very balanced.”

These distinct categories create an engaging experience for the audience, who are guided through Ryder’s highs and lows by clever wordplay. Lines lead seamlessly one into the next, propelled by the versatility of her vocals—a standout in tender numbers like “Killing Time” where the lyrics set an intimate scene against a crisp drum beat, allowing her raspy timbre to soar through vocalizations displaying the underlying vulnerability. Embodying Utopia’s balanced category is the album’s first single, “Got Your Number”, an empowering breakup anthem with non-stop numerical puns. The song is an approachable access point to Ryder’s quick wit, finding fun for the listener even in a heart-wrenching event—existing in that ever-important middle state.

“That’s the balance we’re all looking for, I believe,” Ryder says. “Everybody thinks that if you’re a spiritual person that you have to be all on the right side, and all bright and perfect, and never drink, and never eat badly, and never say fuck—but it can’t be the opposite either. It’s actually a marriage of the two that makes up that balance. So that’s what utopia means to me—that grey area.”

Three years in the making, Utopia is not as blissful as the title might imply—or even as Ryder first imagined.

Every aspect of Utopia is grounded in Ryder’s triangular symbol and the tale of the two wolves—a connection made stronger through her research into her Ojibwe heritage. “It’s funny, because even before I really knew a lot of that, I was really drawn to the story of the wolves.”

Using the wolves’ battle to form a connection between opposing sides, Ryder does not shy away from pain nor does she strive for euphoria. And even though the album has been finalized, allowing her to breathe a sigh of relief, the journey never ends. “You just don’t know. Questions are always there,” she says. “And when the record’s out, there’s a whole bunch of answers you can learn from.”

Making music has become a continuous system of one emotion feeding into another, crafted from Ryder’s joy, despair, and everything in between to form her own little utopia.

Photo by Richard Sibbald.