-

Piero Bambi, the son of company co-founder Giuseppe Bambi, pulls an espresso shot at La Marzocco headquarters in Scarperia, Italy.

-

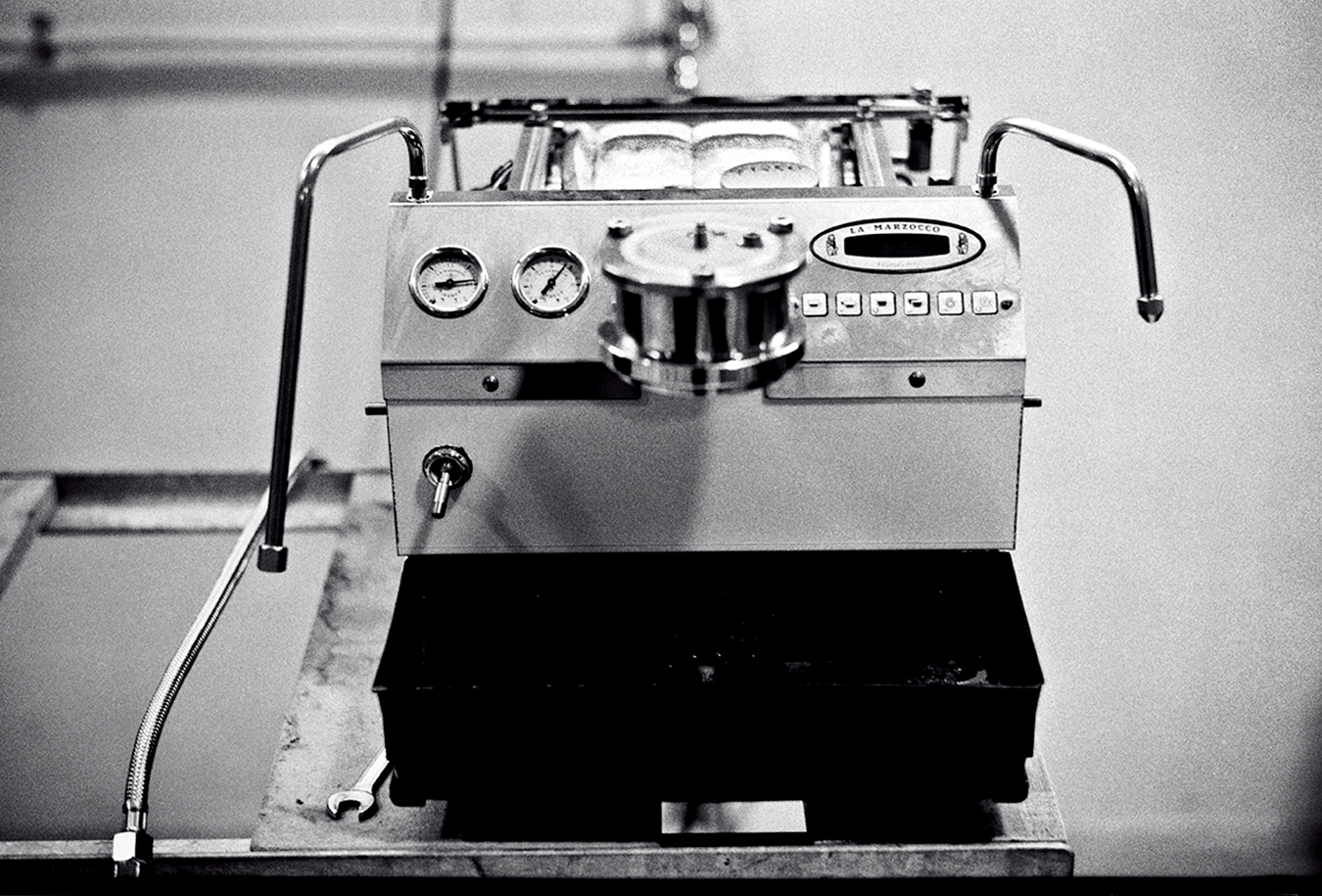

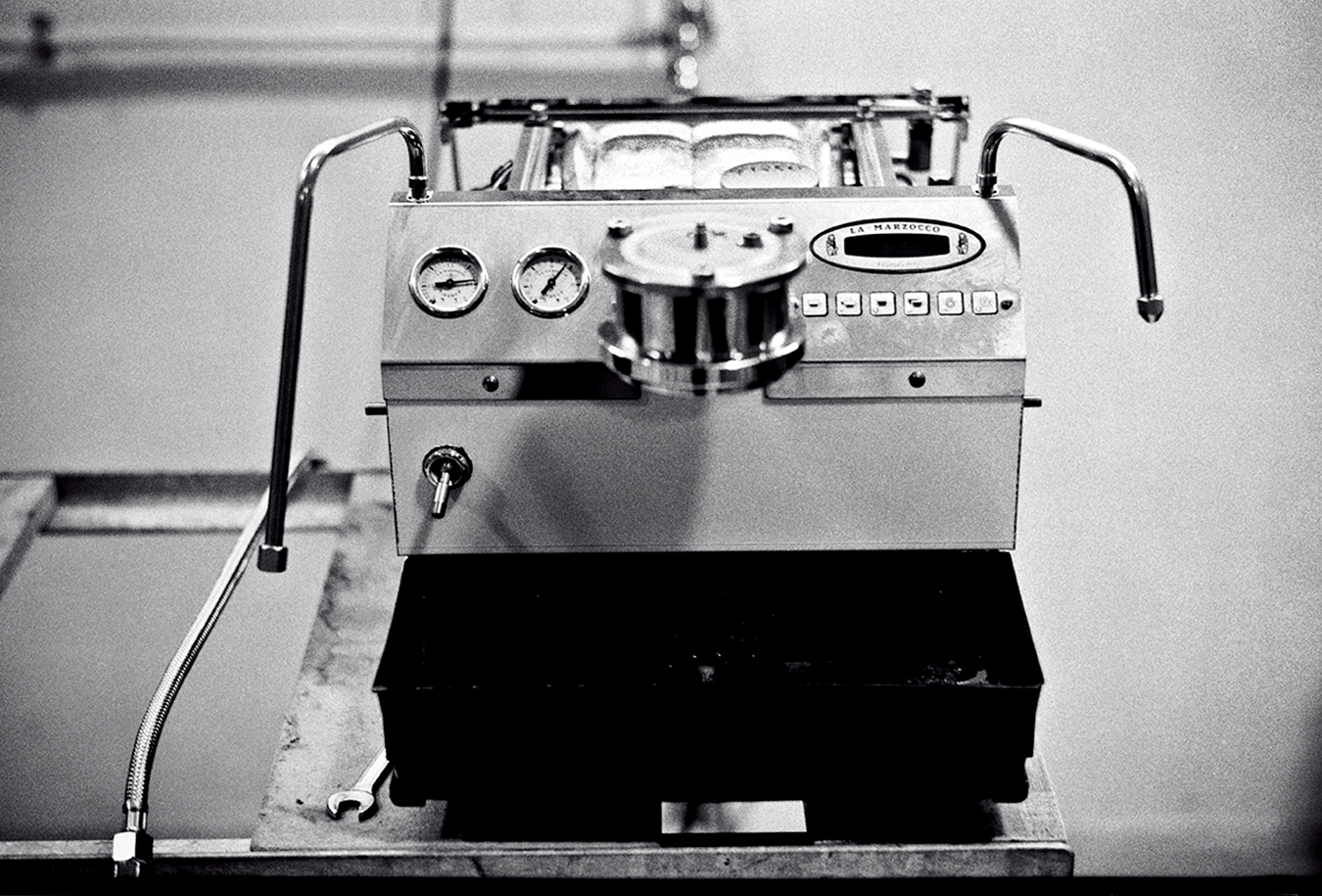

La Marzocco’s FB/80 model was released in 2007 to commemorate the company’s 80th anniversary.

-

La Marzocco’s company emblem, a lion, is fashioned after Donatello’s statue, Il Marzocco.

-

La Marzocco’s GS/3 home espresso machine.

La Marzocco’s Historic Espresso Machines

Made in Italy.

To find the maestros of the perfect coffee brew, look to Italy. For decades, a group of businesses, many still family owned and operated, have tinkered away to make the caffeinated beverage better. Famous for their espresso, small shots of brewed coffee that first came into vogue at the start of the 20th century, Italians have worked tirelessly on improving the drink’s preparation.

Espresso’s popularity beyond Italy has grown substantially since the 1980s, and we are now awash in a wave of espresso-based beverages marketed by Starbucks and innumerable other coffee chains and shops. But the world of java as we know it today was shaped by Italian innovation in the 1930s.

In 1939, brothers Giuseppe and Bruno Bambi of Florence helped revolutionize the design of the coffeehouse espresso machine. The pair had opened a workshop in 1927 in the birthplace of the Renaissance to build coffee machines, drawing on metalworking skills that they previously used to make components for horse-drawn carriages. Proud of their roots, they named the company La Marzocco, drawing inspiration for the logo from the heraldic lion (“Marzocco”) that is a symbol of the Florentine republic and also its most famous likeness in the form of a statue, carved by Donatello, in the Tuscan capital’s Piazza della Signoria.

La Marzocco’s FB/80 model was released in 2007 to commemorate the company’s 80th anniversary.

When the two siblings entered the market, the typical device used in cafés was an espresso machine resembling a tall, bulky cylindrical column of metal with a vertical boiler inside that would heat water which was pushed through the ground coffee with the help of steam pressure. These machines forced water through lightly compressed grounds at a low pressure, making java that looked closer to something one might expect from today’s filtered coffee than a proper espresso served by a skilled barista.

Mindful of the tight space behind a typical coffee shop counter, the Bambis engineered a horizontal boiler and encased it in an elongated metal chassis. Named the Marus, the device featured a detachable cup to hold the coffee grounds, which baristas constantly refilled throughout the day when making shots. The machine’s horizontal arrangement permitted several baristas to prepare espresso at the same time—rather than having to work around it, as with the vertical machines—reducing wait times for customers in need of caffeine.

Seventy-five years on, all that remains of the groundbreaking machine is a signed copy of the patent and the original blueprints. Metal was a precious resource at the start of the Second World War, and many of the devices created by the Bambis in the earlier years of their career were melted down for scrap and reused to make newer models.

But the legacy of the Marus still lives on in the thousands of café espresso machines that replicate its functional shape. The horizontal design, which also allowed for space on top of the machine to store and heat demitasse cups before serving, quickly became an industry standard after the Marus’s patent was left to expire during the Italian bureaucratic upheaval following the war. Rival designs debuted from competitors like Cimbali, Faema, and Gaggia—all firms that would soon become big players. As a result, fame proved elusive for the Bambi brothers.

Not to be discouraged, the duo continued to improve upon their brewing technology while styling the exterior of their machines with subtle aerodynamic curves, which recall the automotive design popular during Italy’s postwar economic boom years. In the 1950s, the industry shifted to hand-powered machines with spring-piston levers (thus the expression “pulling a shot of espresso”) which pushed water through coffee at between eight and 10 bars of pressure. This technique was a new method of coffee extraction and led to a better-tasting espresso that was close to how the drink is served today. (According to consensus in the coffee world, espresso should be brewed at nine bars of pressure at approximately 93°C for 30 seconds, resulting in about 30 millilitres of thin, dark syrup that is extracted from seven to eight grams of coffee.)

While the competition looked to seize on Italy’s economic boom and expand nationwide, La Marzocco remained a family-run outfit that catered mostly to a local clientele in Tuscany. In many cases, the company designed entire coffee bar interiors for clients, but typically it produced small series of a few units and custom-built machines.

“My family has been influenced by Florence and the arts, where timeless works of beauty were built by hand by teams of artisans,” says Piero Bambi, the son of La Marzocco co-founder Giuseppe Bambi.

These days, the Bambi family is represented by Giuseppe’s son, Piero, who is still active in the firm as a designer-engineer despite having just celebrated his 80th birthday this past January. At the company’s headquarters in Scarperia, 30 kilometres northeast of Florence, the bespectacled Piero Bambi points out that the facility’s set-up is less assembly line and more a mechanic’s workshop. “It’s very much an artisanal process, with steps still done by hand, and where customers are able to choose specific colours and detailing for the outside of their machine,” he explains, showing off several newly welded chassis of the Linea PB model (named after Piero’s initials).

The heart of any espresso machine is the brew boiler, which starts out life as a tube of corrosion-resistant stainless steel. In 1970, when Piero became involved in the design of the machines, La Marzocco became the first producer to put two separate boilers in an espresso machine with its GS series; one supplied steam and hot water, with the other dedicated to water used for coffee extraction. The saturated brew groups were attached directly to the coffee boiler which allowed water to continuously circulate in order to maintain a constant temperature, a key factor in the making of quality coffee; indeed, getting to a stable water temperature of around 93°F has been one of the main focuses of innovation in the creation of good espresso over the past decades. (In the electrician’s workshop, Piero shows off an almost-finished espresso machine frame incorporating electronics that manage temperature, time, and pressure to ensure that water saturates the grounds within the parameters set by the barista.)

In any department at La Marzocco’s factory, the first thing one notices are the trolleys. After each phase is completed (welding the boiler, electrical wiring, and so on), a worker pushes the partially built machine on its cart to the next station. There’s no manic rush or constant humming of robotic arms to be found in the factory. “My family has been influenced by Florence and the arts, where timeless works of beauty were built by hand by teams of artisans,” says Piero, who notes the brand builds fewer than 7,000 machines a year, with the bulk commercial machines for cafés costing upward of $20,000 (U.S.). “It’s the same thing here. We have no desire to do large-scale production but instead focus on craftsmanship. It’s in our DNA.”

In the staff canteen, which naturally includes a coffee bar, Piero bumps into Kent Bakke, the American-born CEO of La Marzocco. In the 1970s, Bakke was already ahead of the curve in the United States by serving Italian-style espresso at his Seattle eatery, and he has long been a fan of the brand. In 1978, after closing his restaurant, Bakke was eager to import espresso machines to North America and decided to visit Italy to see the manufacturers first-hand. He met with Giuseppe and Piero Bambi, and La Marzocco’s open outlook to working with different cultures appealed to him. He also loved the company’s dedication to handmade detail. Bakke would soon be responsible for giving the small Tuscan company its big break: in 1987, a then-fledgling Starbucks became a client of Bakke’s import business after one of its Faema machines broke down and its baristas found the La Marzocco replacement far superior.

La Marzocco’s GS/3 home espresso machine.

The precision engineering of La Marzocco’s Linea model soon resulted in Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz asking for hundreds of machines, and a factory was temporarily set up in Seattle to meet demand. In 1994, Bakke assumed part ownership of the business from Piero Bambi to help steer the company toward expansion.

Since then, the firm has done well, although there have been challenges. In 2000, Starbucks—which was working on a worldwide store rollout and eyeing bigger earnings—decided to switch over to fully automated, Swiss-made espresso machines that, many said, lowered the quality of the brew. (Notably, there are select flagship locations around the world that continue to use La Marzocco machines, including the very first Starbucks location in Seattle’s Pike Place Market.)

“There’s a lot of passion and excellence in what we do here, and I want to keep that same family-run philosophy. We strive to work closely with our customers,” says Bakke. The bulk of sales are still geared toward cafés, although La Marzocco also unveiled its sleek GS/3 in 2007, a machine aimed for the home market.

Luckily for La Marzocco, the appearance on the market of the second-hand Linea machines that had been used at Starbucks coincided with a significant rise of independent café owners and roasters. This so-called “third wave of coffee” resulted in demand for top-of-the-line equipment to prepare extensively researched single-origin coffees. Indeed, attendees at trade fairs where La Marzocco exhibits rhapsodize about the espresso aromas in much the same way wine lovers wax lyrical about Premier Crus.

The craving for espresso, double lattes, and the like has exploded worldwide. Indie coffee shops are now all the rage. Coffee has, arguably, never been more popular. And a family-run Italian brand that has roots stretching back over 70 years is still experiencing remarkable success; indeed, La Marzocco has quietly positioned itself at the high end of the market. “We make them like Ferraris,” says Piero, “and you can taste the difference in the coffee.”