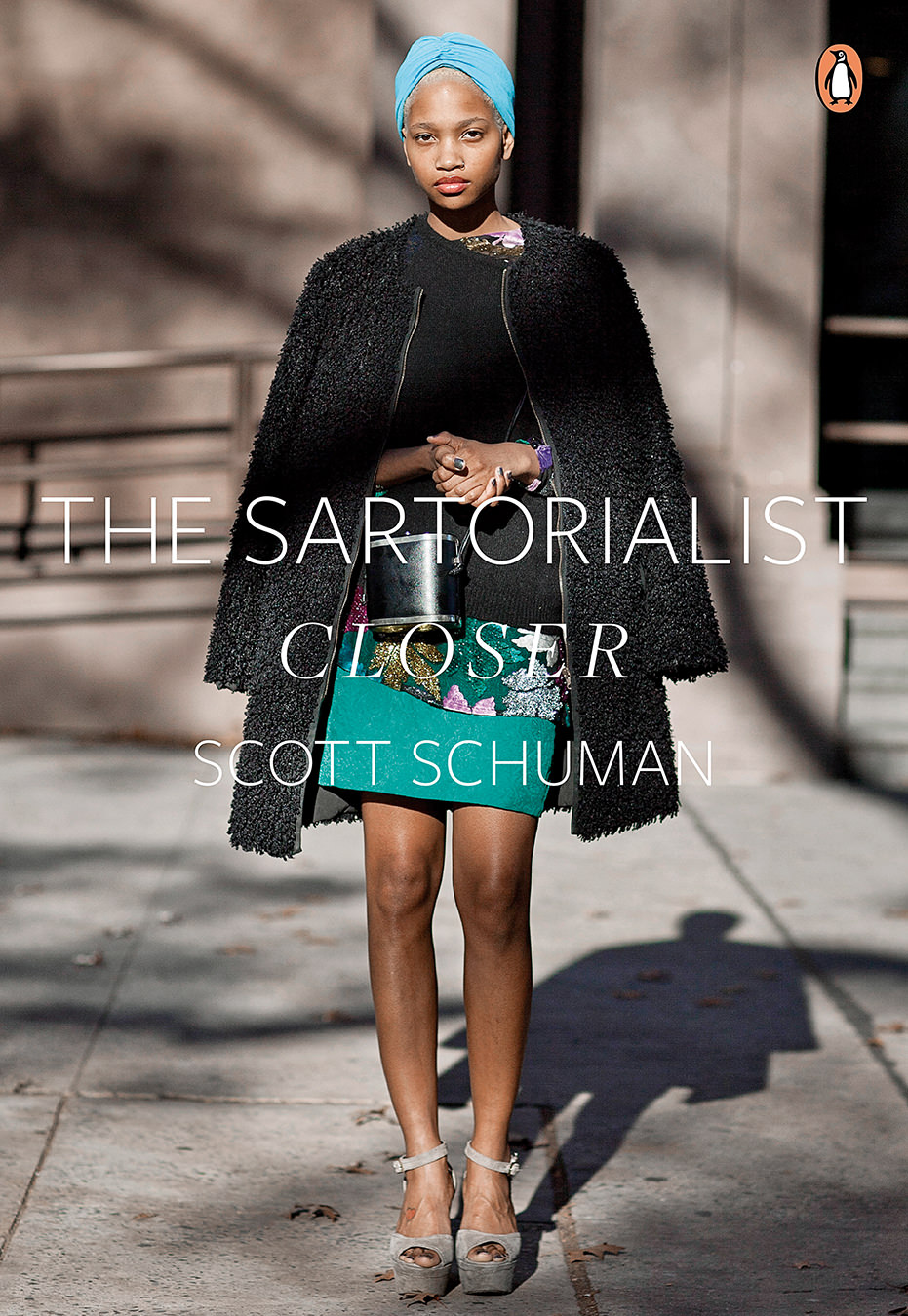

-

-

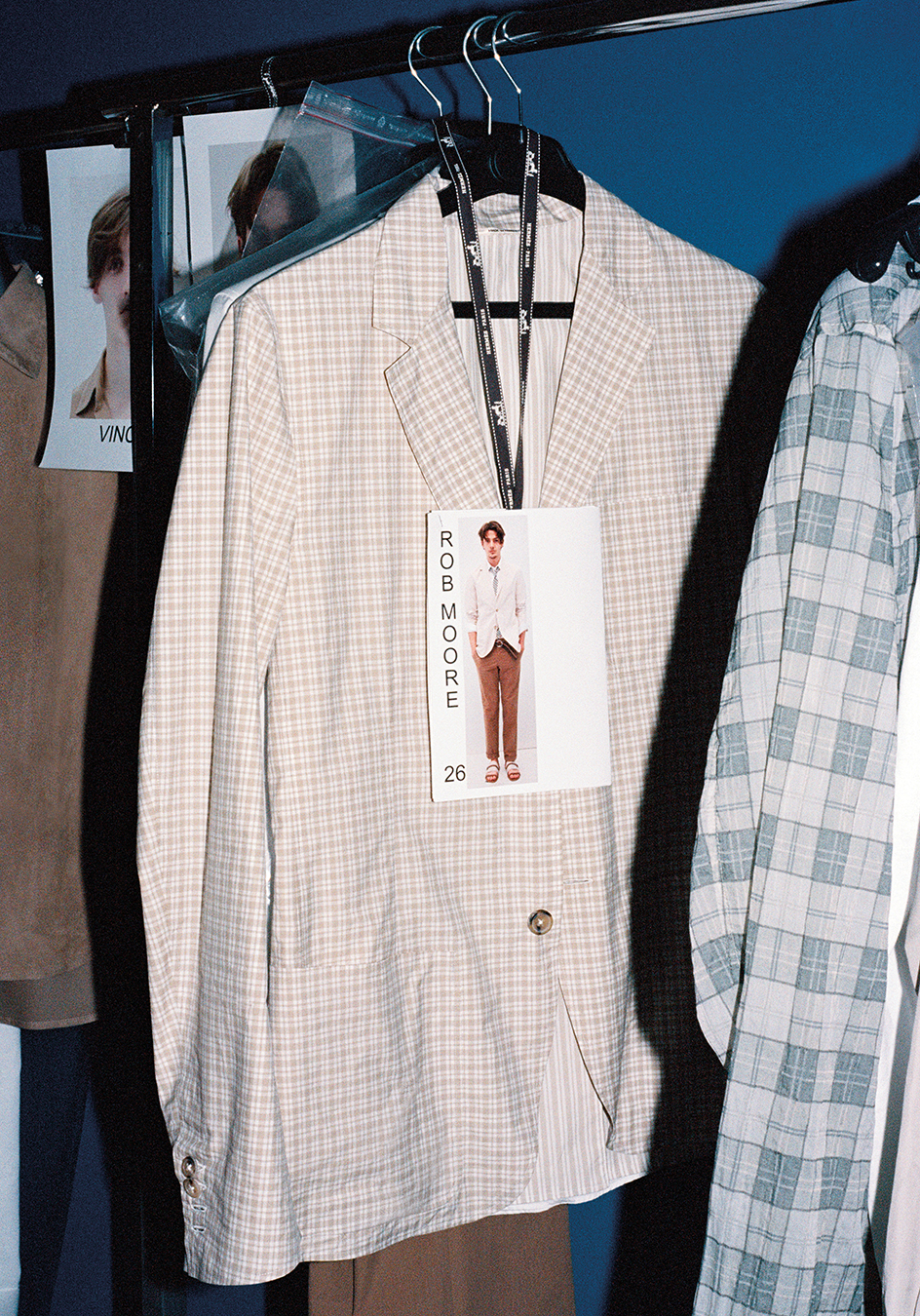

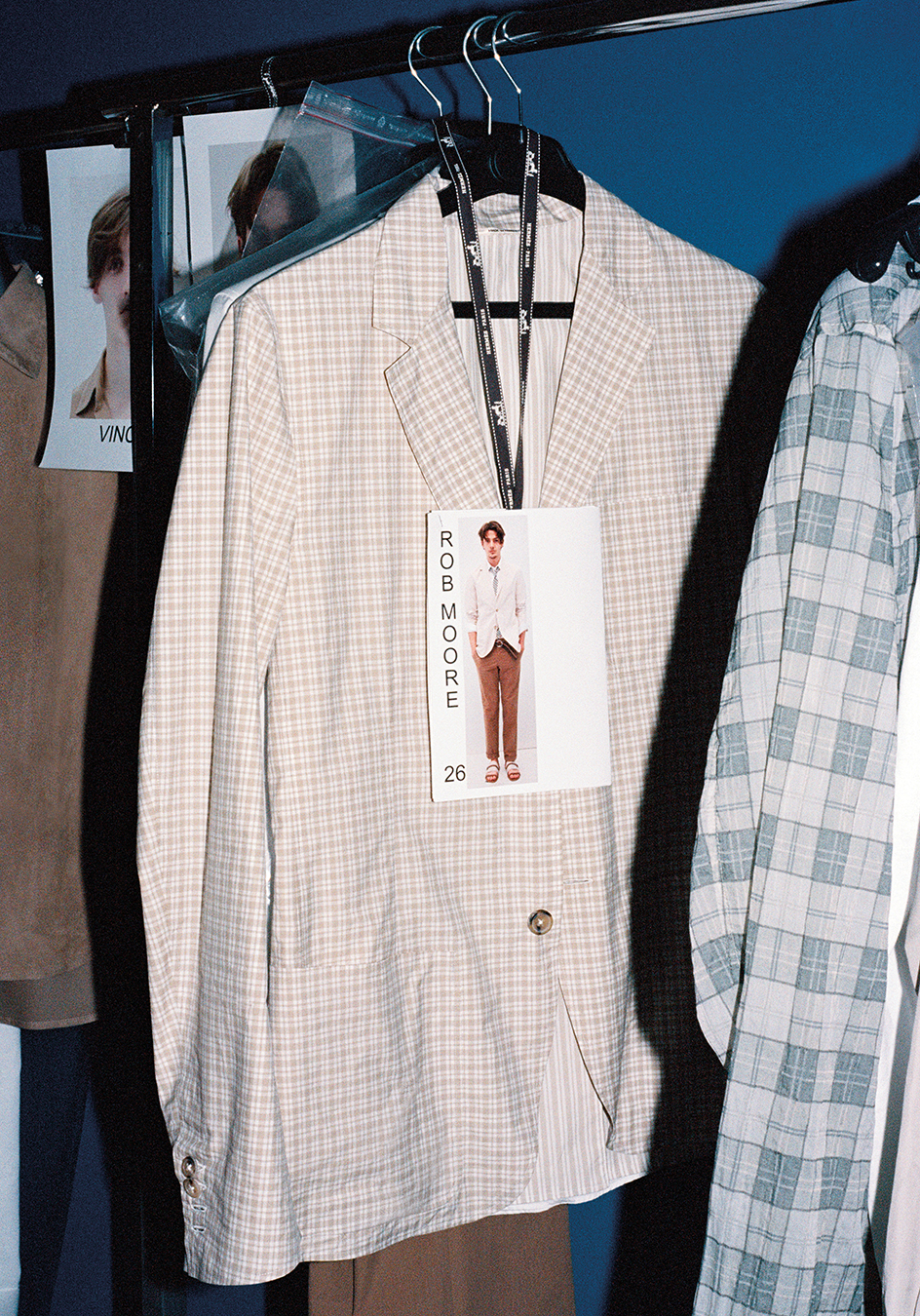

Behind the scenes at the Hermès spring/summer 2011 collection fashion show at Les Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais in Paris.

-

-

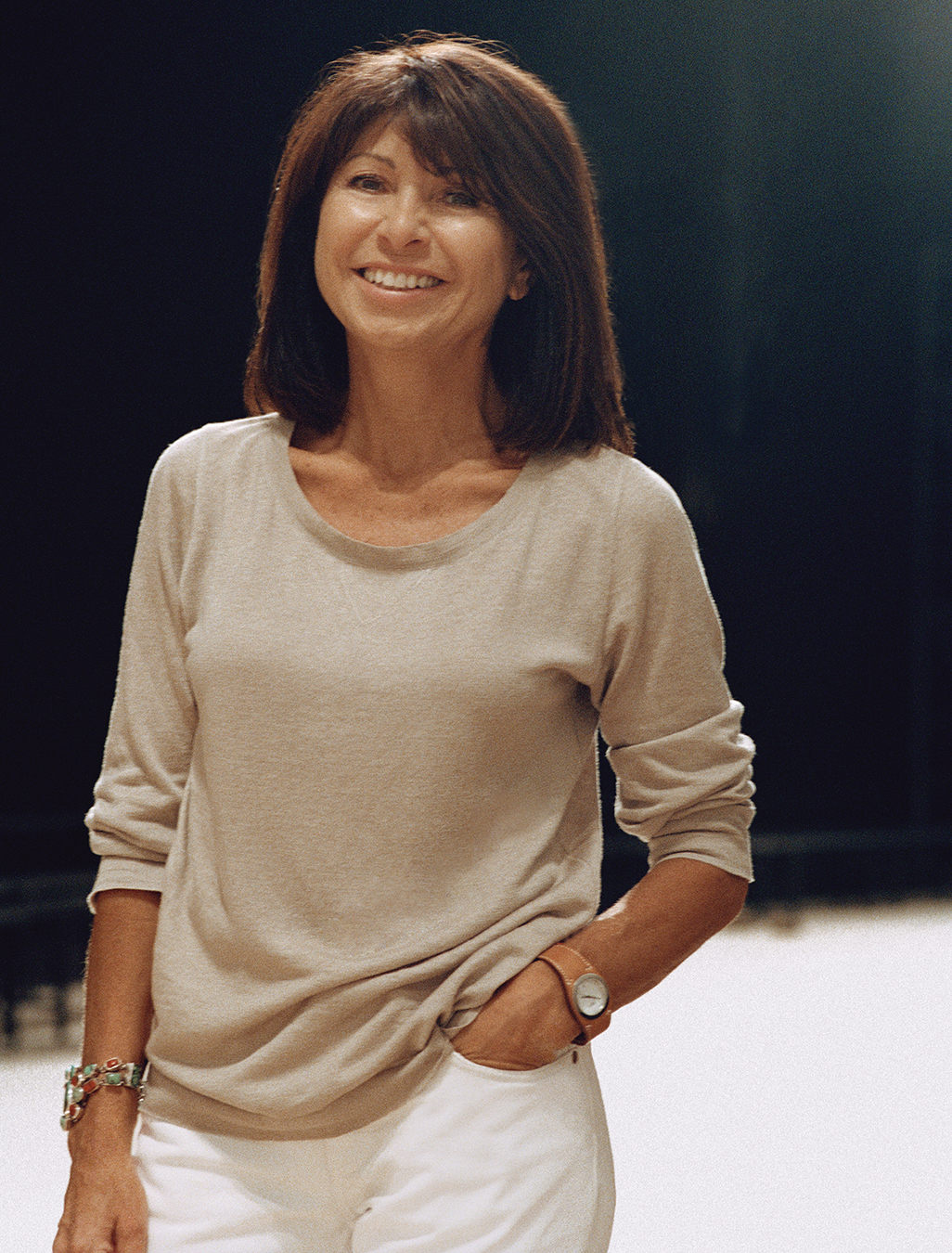

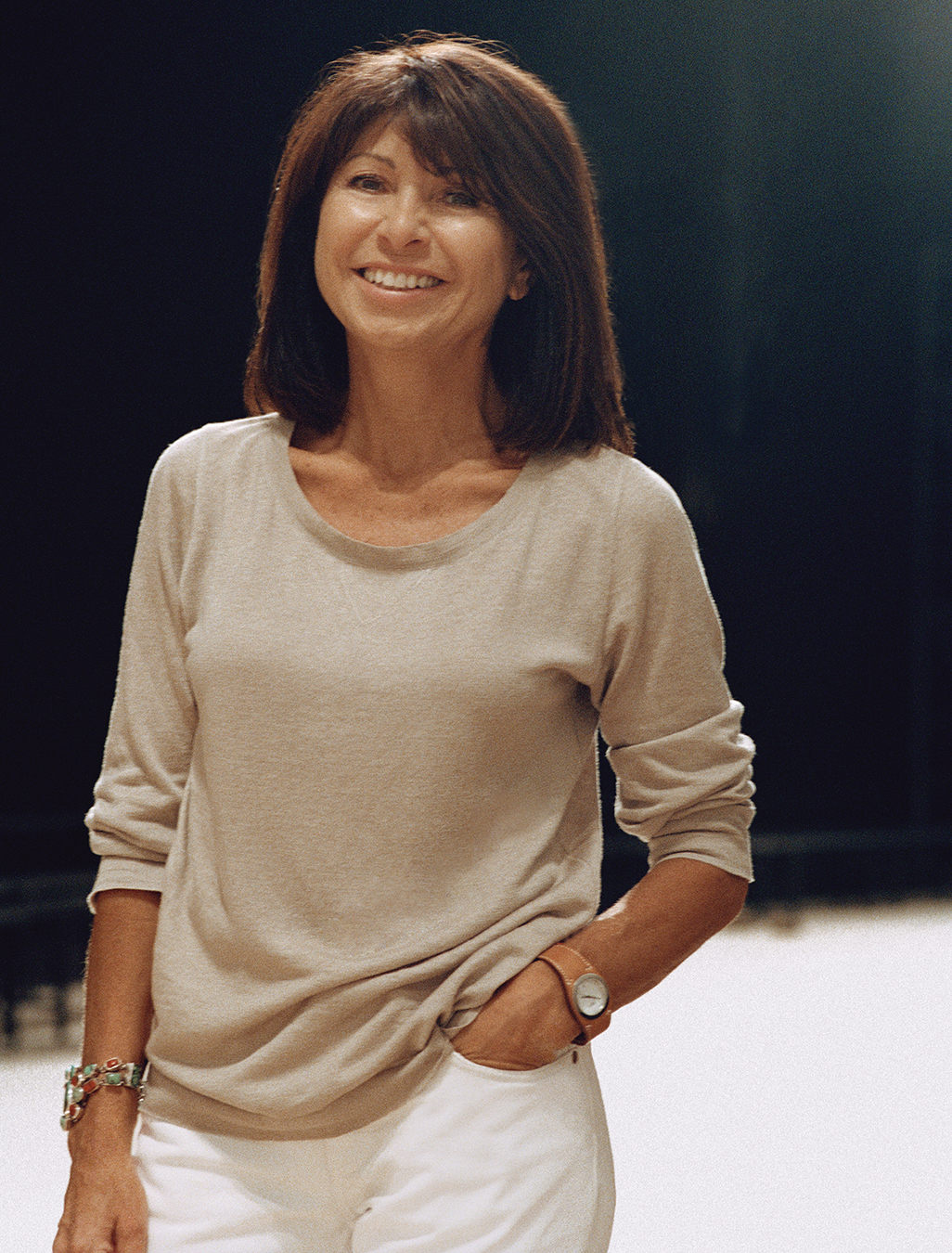

Véronique Nichanian

Hermès for him.

Even among rival brands, Hermès is a standard bearer of savoir faire, craftsmanship, and a symbol of understated French elegance. Yet there is also a philosophical element present here, one that is rooted deeply in the culture of refinement. You could, in fact, even say that the improbable is the essence of the Hermès product.

The company seems to thrive on the tension borne of the mélange of contemporary and heritage tastes. Among other innovations, Hermès was the first to introduce the zipper in France, in 1923, after Émile Hermès spotted it on a trip to Canada. More recently, the maison raised eyebrows with its 2003 hiring of Jean Paul Gaultier—the bad-boy designer, known for conical bras and promoting the use of skirts by men—to design its ready-to-wear for women. The result was debatable—but in many ways, Gaultier’s parisiennisme, master tailoring skills, and overall quirkiness were a fit for the house. (Gaultier recently left the company after seven years to focus on his own label, in which Hermès has a 45 per cent stake. He was replaced by Christophe Lemaire, late of Lacoste.)

Behind the scenes at the Hermès spring/summer 2011 collection fashion show at Les Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais in Paris.

Hermès is one of the oldest family-owned companies in France; it was founded in 1837 by Thierry Hermès as a saddle and harness-making business on rue Basse-du-Rempart in Paris. The company has become renowned for its handcrafted leather goods (including fashion’s most exalted handbags, the Kelly and the Birkin). What distinguished Thierry’s work was a signature definition of quality. Since then, the company has become the definitive authority on excellence.

And yet, despite the distinct renown for the company’s products and quality, there is even much more to be said for the people who craft the Hermès creations. And in her 22-year tenure at Hermès, menswear designer Véronique Nichanian has solidified the company’s reputation, guiding the creation of menswear pieces so luxurious that they have attained revered status among a certain set. For years, Nichanian’s sense of mystery and qualified discretion have piqued curiosity; hers is a habit, as observed at the biannual fashions shows in Paris, of coming out only to take a quick bow, avoiding the typical post-show interview and instead disappearing backstage. She prefers, it would seem, to let her clothes do the talking.

Even as Gaultier’s tenure at Hermès was causing headlines—and actually long before this—Nichanian was posting defying results. Gaultier’s departure, coincidentally or not, comes at a time when we are seeing a broader trend that reflects the growing importance of menswear to a fashion house’s bottom line. (According to market research company Euromonitor International, sales of men’s designer clothing have risen at twice the rate of women’s over the past five years.) According to Guillaume de Seynes, executive vice-president of Hermès International and a member of the sixth generation of the Hermès family, fully half of the company’s estimated $4-billion in annual sales are attributed to men’s items.

By design or not, it seems like Nichanian’s time. It certainly has been her year, starting with the opening in February of Hermès’s first store dedicated solely to men (the four-storey ode to masculine luxury is on Madison Avenue in New York), and ending with her being given a Légion d’honneur. In between, she presented two collections that are among her best to date.

In the company’s headquarters, six floors above the legendary Hermès flagship at 24 rue du Faubourg St-Honoré, Nichanian wears a dark V-neck cashmere sweater and slim black trousers along with an Hermès double tour watch, her dark hair in its customary, youthful shoulder-length bob. She is a monochromatic counterpoint to her all-white, sanctuary-like office. She has been referred to as “the quietly subversive designer behind Hermès menswear.”

“Yes, I suppose I have tried to achieve a kind of radical continuity,” she says. “I try to aim for harmony, but at the same time, I like to shake things up. You have to have a sense of humour as well as a feel for striking details.”

As a girl growing up in a Paris neighbourhood dominated by fabric shops, says Nichanian, she spent “hours in those stores, feeling the fabric, buying armfuls of material,” all for the sheer pleasure of the fine materials. As she talks about fabric—cashmere, wool, linen, leather, suede (“j’adore un très beau whipcord”) she becomes animated and her eyes brighten.

A similar joy emanates from her as she describes designing for the Hermès man. “There is no one Hermès man—there are many,” she explains. “It’s a question of style, not fashion. I want to define contemporary elegance—a wardrobe of things that are sober and chic, yet comfortable.”

After studying women’s fashion design at the noted École de la Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne, Nichanian was hired by menswear designer Nino Cerrutti. “I was surprised by how much I enjoyed the challenge of menswear,” she says. During her time with the Italian company, she travelled throughout Europe, sourcing hand-loomed wools in Ireland, or cashmere in Italy, and making contacts with the crème of European textile manufacturing. Nichanian stayed at Cerrutti for 11 years, until the Hermès boss at the time, Jean-Louis Dumas, saw in her a stickler for perfection that was reassuringly Hermès, and lured her to the French house. (Dumas was in declining health when he retired in 2006, leaving the company to the sixth generation. He passed away earlier this year.)

“There is no one Hermès man—there are many,” explains Nichanian. “It’s a question of style, not fashion. I want to define contemporary elegance.”

Hermès started designing men’s clothing in the 1920s. It wasn’t until 1949, when the company started making its colourful printed silk ties, that it gained a larger male audience. Still, when Nichanian was brought on board, the goal was mainly to broaden what the company thought was lingering perception among some men that “Hermès is just a tie company.”

Though Nichanian has done much to change that perception, she says, “I am not doing fashion but objects of clothing. Fashion is marketing—it’s consumption. I treat clothes like individual pieces, like objects, because Hermès is for me a maison d’objets.” It seems improbable that such lofty ideas and philosophical goals (for example, Jean-Louis Dumas eschewed the word luxury, believing it to connote desperation; avoiding the word is a convention that’s been adopted by the current generation) would make for such a profitable corporation. Nonetheless, such appears to be the situation in le monde Hermès: the improbable becomes tenable when you create your own world on your own terms.

Case in point: Nichanian was among the first designers to experiment with matte finishing on nubuck crocodile. “When I first thought of doing a matte crocodile waistcoat, the leather craftsmen told me it couldn’t be done,” she recalls. “But they did it for me.” This fabric research is what keeps Nichanian inspired.

The Hermès family has empowered its artisans with their own creativity. And there certainly appears to be an absence of conventional profit-cost analysis in the making of anything Hermès. An artisan can take from 10 to 20 hours to complete a Kelly bag and from 12 to 24 to complete a Birkin. It takes 300 silkworm cocoons to complete one 90 x 90 carré scarf. And, a bespoke men’s suit, cut and sewn entirely by hand, takes up to 100 hours to craft.

Part of Nichanian’s talent is her ability to see a world of change in the way, for example, that a shoulder sits from one season to the next. “Designing menswear is a purer exercise in style,” she says. “The rigour of it is inspiring.” Nichanian sparkles again when she speaks of the tomber d’une manche—the way a sleeve falls. “There is such refinement when you are working on proportion, the proportion of a cuff, the length of jacket. You are working to the exact millimetre. It’s very subtle, and very challenging.” With perhaps a soupçon of bias she adds, “Womenswear is more about the podium extravaganzas—and then what? You have a white shirt in the store.”

Bold touches of colour have always characterized Nichanian’s collections. “Colour is an affirmation of personality,” she says, “and one of the best way to enhance wardrobe classics.” In her fall/winter 2010 collection, a cornflower-blue cardigan peeps out of a muted grey suit, and a neoprene orange pinstripe accents another pale grey wool jacket. For spring/summer 2011, the collection re-creates things like the khaki suit, the linen suit, casual-chic printed silk blouses, and trimmed pants with plenty of warm colours, including plenty of white and beige with accents of teal, blue, and green. Each collection is designed to evolve from the last; as such, a man can always find a boldly coloured sweater to wear under a jacket from the previous season. Her menswear flatters the body in a way one might expect of women’s couture, and yet—and this is crucial to the North American man who still thinks of high male fashion as the realm of the Left Bank Dandy—the clothes retain a very distinctive masculinity.

The defining piece in Nichanian’s first collection in the early years at Hermès was the jacket. “I explained to Jean-Louis Dumas, we have to create an Hermès jacket that will exist 20 years from now, something iconic for men like the Kelly bag for women. It will have a particular shoulder, an Hermès cut,” she says. And, more than twenty years later, “a three-button jacket with a softer shoulder still is timeless, and I am very proud of it.” The proportions of the lapel and shoulder have been adapted over time, but, at the same time, “it’s the same as it was since the beginning.”

In conversation, Nichanian manages to be both forceful and girlish. She seems to possess, not exactly joie de vivre, but something better: appétit, an especially alluring quality when combined with French chic. Her style philosophy is être sans avoir l’air, being without seeming to. In other words, don’t try too hard. Over the years she has seen men embrace this idea, a frankly Parisian notion. “I think Parisian men feel freer to express themselves in their way of dressing, and mix things in a personal way,” she says (like many in the style world, she differentiates between Parisian men and French men). “I like this freedom, and because of it, I am very tolerant about fautes de gout [errors of taste].” North American men, she says, “are really sensitive to social codes. Even something like casual Friday is so codified … [such as] chinos and a polo shirt. But that is definitely evolving.”

Last year, Pierre-Alexis Dumas named Nichanian artistic director of the “Masculine Universe”, expanding her role beyond the prêt-à-porter to the entire realm of the male lifestyle. And once again, Nichanian proves she’s a sure bet. The new New York store—known as Man on Madison—is “doing amazing,” she says. “Better than our expectations, in fact.” The space exudes a look of masculine elegance. The first three levels proffer lavish leather goods, silk ties, sportswear, knitwear, and other luxuries while the fourth floor is devoted to bespoke and made-to-measure; not just suits but everything from ties and sweaters to jacket linings can be made to specification. (Nichanian describes it as “a perfect walk-in closet.”)

Hermès represents more than the bright bling of a shiny “H” on the waist or wrist or silk tie or scarf. In fact, it is one of the few—and perhaps the only—maisons de luxe for which the object itself, not the logo, imparts its status to those who recognize it. Hermès occupies a different realm than brands that have bowed to the gods of marketing. It is a status granted by those who can understand and recognize the work behind the object, the ideals, the tradition, and the beliefs that have made its creation possible.

The Hermès tradition and vision is a celebration of hard work and a quest for perfection, which Nichanian confirms. “If something isn’t perfect, Hermès has given me the time and money to rework it again and again until it is,” she says. In fact, what Hermès attempts to offer cannot, in truth, be bought. Hermès turns something, no matter how improbable, into the exquisite.