What’s at Stake in the Race for Digital Education?

When thinking about the future of digital education and digital learning, two dominant tropes come to mind. First, a student or group of students completely wired into the system, downloading information rapidly, eyes flickering. Second, the student at home, barely paying attention, as the countless buzzes, whirs, and blips of the screen distract or draw them into the echo chambers that proliferate there. But, like many things in the contemporary world, the reality is far more boring (whew) than many dystopian sci-fi writers of the 20th century anticipated.

During the ongoing COVID pandemic, we as a society have had to come to terms with the problems and opportunities of digital learning, which designates both the use of new technologies to modulate the learning experience as well as distance learning.

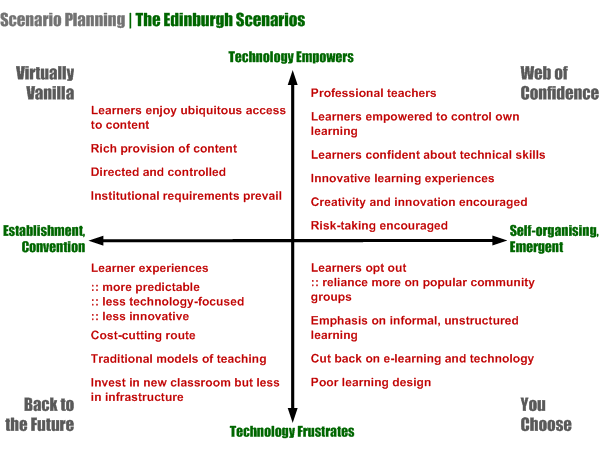

Digital education did not start with quarantine measures. As early as 2013, 32 per cent of U.S. students at all levels were taking at least one fully online course, and the number during quarantine has likely risen significantly. Anticipating these shifts from the traditional classroom to the digital in 2004, researchers laid down a road map that has been used to predict the various ways digital education can go. It is called the Edinburgh Scenarios, a name that could title a sci-fi movie but in actuality charts four distinct possibilities along the lines of empowerment versus frustration, and self-control versus standardization (fig. 1).

Figure 1. Courtesy of Jisc.

These themes seem to be at the heart of the conversation about the protocols of digital education, and the specifics can get sticky for those unfamiliar with academic lingo. One thing is clear: the pandemic has swung the bar up, toward a need to empower education through technology, no matter what, because reverting to old systems is no longer an option. But what does this empowerment look like? In the introduction to The Future of E-learning, Jon Dron and Terry Anderson—associated with Athabasca University, the first Canadian university to focus strongly on distance learning—acknowledge a tension between the creative individuality of distance education and “hardening, efficiency-building approaches to learning.”

These efficiency-building approaches touch on goosebumps-inducing methods of control like learner-producing machines—but also point to methods like timetables and curricula that work to standardize education as we have known it. While creativity and gig tutoring present a nice version of the educational experience, I think most would agree that certain aspects of liberal education require a sense of shared history and knowledge of the civic system. We need creative solutions to this digital either/or scenario.

While creativity and gig tutoring present a nice version of the educational experience, I think most would agree that certain aspects of liberal education require a sense of shared history and knowledge of the civic system.

Lauralee Sheehan is a former indie rocker and founder of Digital 55—a collective that tries to find empowering and inclusive intersections between storytelling, design, and digital education. Sheehan recently designed a course in partnership with Athabasca to teach people in leadership positions how to deal with the pandemic, which makes clear that the ins and outs of digital learning go far beyond the instruction of school-age children. She hopes to disrupt traditional teaching methods that can leave learners who don’t fit the mould by the wayside.

Sheehan believes in a blended approach that combines face-to-face human interaction (distanced or in person), traditional teaching methods and evaluations, and technological mediums that best suit the learner. “By the nature of the crisis—digital has to be a thing that is part of the whole experience,” she says. “That has to happen really quickly, but not taking away from the other aspects of learning and development. For the future, a more blended, fluid approach has to happen.”

While some vestiges of the traditional model of teaching will necessarily fall away, Sheehan thinks that there are still ways to disseminate the same information without sacrificing learner-based approaches that allow for “fluid and curated” tools. At the heart of this is a focus on “project-based learning and real world connections.” How many times have children and even adult learners complained about the inapplicability of text-book-based learning for regurgitation and grades? I know I did.

At the heart of this is a focus on “project-based learning and real world connections.”

Real-world connections allow for the learning of aesthetics and politics for generalized expansion of the mind in a way that situates these learnings in context and thus in memory and life. In an almost shocking passage of their introduction, Dron and Anderson write the following about project-based technologies: “Such tools enable learning to be embedded in practice, as part of the process of living, rather than demanding a separation of life and education. In this way, the pedagogies suggested by these affordances bear more resemblance to those employed by hunter-gatherer tribes and informal apprenticeships than those used in formal teaching.”

An interesting idea—technological applications of curated learning experiences that have a bearing on life bringing us closer to human modes of education that endured for thousands of years. Instead of reading this like a cringe-worthy moment of nostalgia for lost time, one could read it alongside Sheehan’s insistence that “all people learn differently” and to learn is to learn from one’s unique position in the world, dealing with the various things life, like the outdoors or a trade, throws at you. We may all need the same sustenance, but we have and will continue to come about it in different ways.

Of course, these strategies don’t answer some pressing questions like: where are the children suppose to go while parents are working? The questions of where and when according to the erratic schedules of the contemporary economy will have to be questions we figure out together as we figure out what the pandemic means.

________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter here.