The Yanomami Struggle, a New Exhibition With Photographer Claudia Andujar, Opens in New York

From her seat in the centre of a small cluster of people, 91-year-old Claudia Andujar takes the hand of Thyago Nogueira, curator of The Yanomami Struggle and head of contemporary photography at Instituto Moreira Salles in Brazil. She pats his hand and whispers in his ear in Portuguese. It’s a small gesture, but one that is strikingly tender and genuine before a full audience of journalists in bleachers. Andujar has close relationships with many of the people who share the stage with her—it’s what her career is built on.

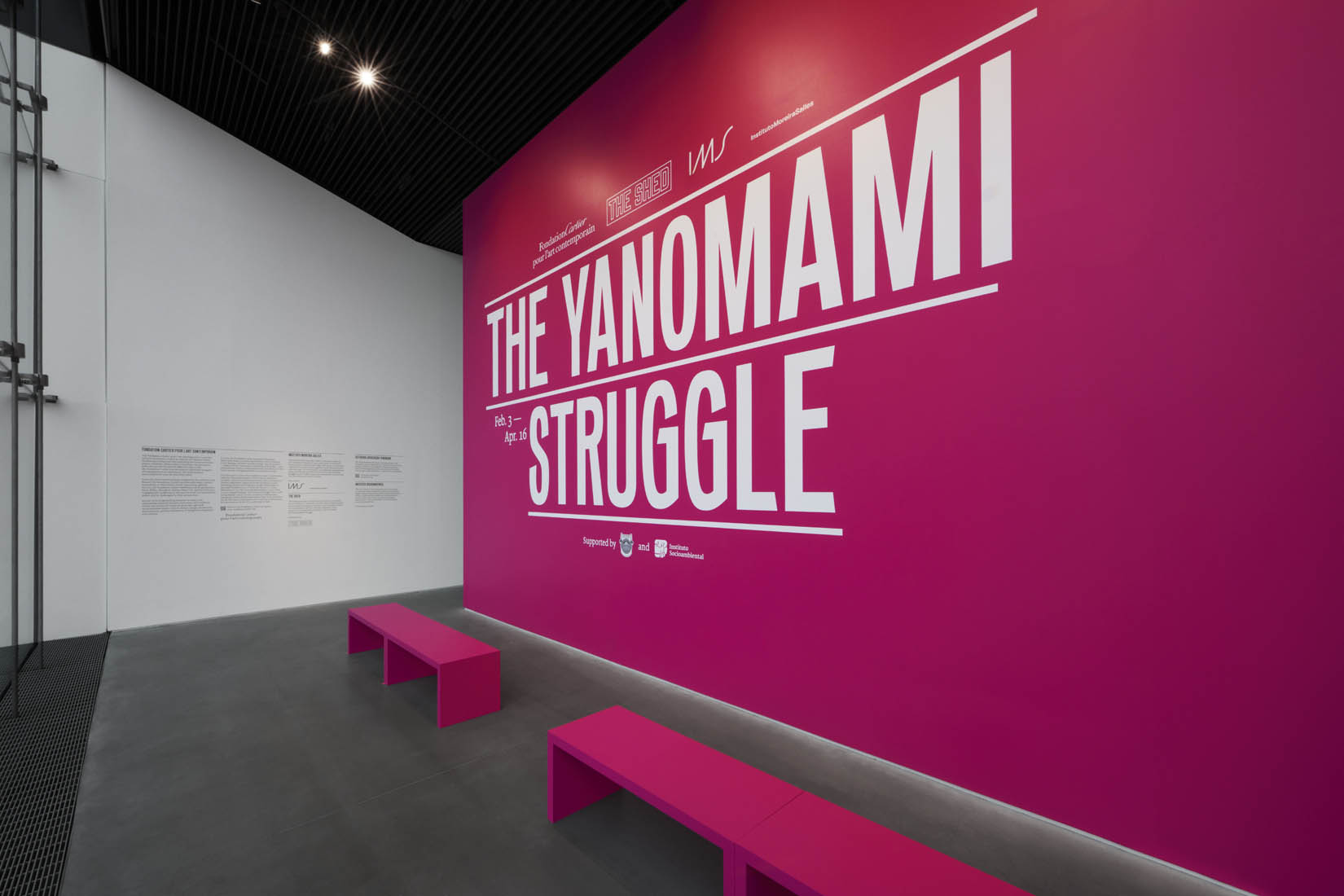

Andujar has spent the past five decades photographing and advocating for the Yanomami people, one of the largest Indigenous groups in Amazonia. Today, at Manhattan’s iconic culture centre the Shed, she is joined by Alex Poots, artistic director of the Shed, Hervé Chandès, artistic managing director of Fondation Cartier, and Yanomami shaman Davi Kopenawa, among others, to mark the North American debut of The Yanomami Struggle, a landmark collection of Andujar’s work presented alongside paintings, drawings, and videos by Yanomami artists, several of whom sit with the acclaimed photographer.

Image by Adam Reich, courtesy of the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain.

Image by Adam Reich, courtesy of the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain.

Image by Lewis Mirrett, courtesy of the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain.

Put on by the Shed, with Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, the exhibition marks an unprecedented look into Yanomami life, with over 200 of Andujar’s photographs that span the time she has spent with the community, along with more than 80 drawings and paintings by Yanomami artists André Taniki, Ehuana Yaira, Joseca Mokahesi, Orlando Nakɨ uxima, Poraco Hɨko, Sheroanawe Hakihiiwe, Vital Warasi, and shaman Kopenawa, and video pieces from Yanomami filmmakers Aida Harika, Edmar Tokorino, Morzaniel Ɨramari, and Roseane Yariana.

Born in Switzerland and raised in Transylvania, Andujar moved to New York City in 1946 to escape the Holocaust before settling in Brazil in her 20s, where she began pursuing photography. In 1971, while working for the Brazilian magazine Realidade, she received an assignment to capture images of the Yanomami people, which would lay the groundwork for a relationship she cultivated and has maintained to the present. Through the years, her role evolved beyond observer and into devoted friendship and activism.

Image by Adam Reich, courtesy of the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain.

Image by Adam Reich, courtesy of the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain.

Image by Lewis Mirrett, courtesy of the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain.

Contemporary Yanomami history is one marked by hardship, from environmental exploitation of their territory through logging, mining, and ranching to exposure to disease from outsiders and violent attacks. After an influx of 40,000 gold miners into the territory in the ’80s, 15 per cent of the Yanomami population died from malaria and infectious disease. In recent years, former far-right president Jair Bolsonaro has been criticized for allowing illegal Amazonia business to run rampant, causing widespread deforestation, whose consequences the Yanomami are still feeling through violent attacks. After Andujar co-founded the Commisão Pró-Yanomami (CCPY) in 1978, she and Kopenawa spent 14 years working to obtain demarcation of a contiguous Yanomami territory, a status that was obtained in 1992 but has been threatened as of late.

“I have been working with the Yanomami for 50 years, and I will continue to do this, to defend them, to defend their land, which has been invaded by illegal miners,” Andujar tells the audience. “We want you to understand that the Yanomami are threatened to disappear if they don’t get any support, and this is why we are presently here, for you to understand who the Yanomami people are. If we want them to survive, we have to understand the situation.” It’s a call to action echoed by the Yanomami and other speakers.

Image by Adam Reich, courtesy of the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain.

Image by Adam Reich, courtesy of the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain.

“We are a people, we have an identity, and we want to show you our characteristics. We want to represent the politics. We want to show you our harmony, our identity, our beliefs, our cosmology, and this exhibit shows that,” Kopenawa says through a translator. “We are from the north of Brazil—we live far. And we are here so that you recognize our struggle and the results of the scars of all the problems that have been happening to our people in the past and right now.”

Fondation Cartier, which supports contemporary artists across genres began working with Andujar 20 years ago for an exhibition in Paris, Spirit of the Forest. Since then, they’ve collaborated on a number of shows that bring awareness to the Yanomami people and cause. The Yanomami Struggle expands upon earlier versions of the exhibition to promote Yanomami voices. “It was really an opportunity to expand and say this is not only a historical fight, but this is a fight for knowledge for learning, and for protection and defence that needs to be expanded and transmitted to other generations,” Nogueira says in an interview later. “So it’s an opportunity not only to see Claudia’s work but to see the new generation that will inherited her and Davi’s fight.”

Image by Adam Reich, courtesy of the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain.

Image by Lewis Mirrett, courtesy of the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain.

The exhibition has two parts. The first is an artistic exploration and celebration of Yanomami culture and society—Andujar’s work is intermingled with that of the Yanomami artists for an extensive and personal look at Yanomami life. In the middle of the room, pieces are suspended by wire in glass frames that seem to float, casting shadows on the floor and inviting viewers to wander through them. The second half, set in an adjacent room, is “more dramatic because it shows images that shouldn’t exist,” Nogueira says: it acknowledges the brutality and hardship the Yanomami have faced. “Early on, I said these images should not live together, we need to show people how art and how photography, drawings, and films can open us to understand the new universe and can teach us from that universe. But we also need to make sure that historical violence against that society is acknowledged and represented so that it’s not forgotten.” A dark room in the back casts Andujar’s audiovisual project, Genocide of the Yanomami: Death of Brazil, which documents the devastation Western aggression has brought to the Yanomami.

“Coming from also a place of displacement, escaping the Holocaust, she has found a new place and has been embraced by that new society,” Nogueira says when asked what her legacy will be to the Yanomami people, many of whom refer to her as a mother. “She has worked to open space for them in the international arena. And so she’ll probably be remembered as the person that gave them the opportunity to be here, to speak for themselves, to be heard by different audiences, and to be understood, maybe, hopefully, by the non-Indigenous world.”

Open to the public on February 3, The Yanomami Struggle runs at the Shed until April 16.