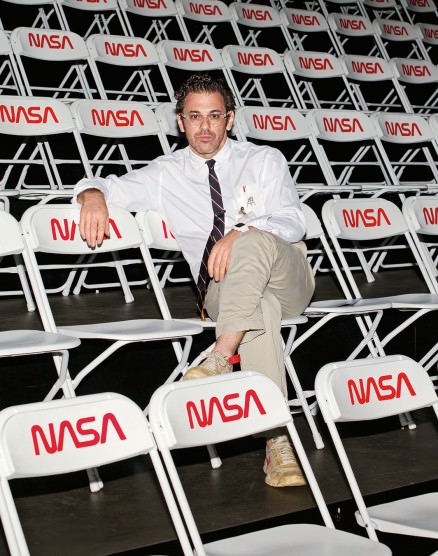

Artist Tom Sachs

Ground control to Major Tom.

When Tom Sachs was eight years old, his father wanted a camera. Since the camera was too expensive to buy, the young Sachs made him one of clay instead. Since the boy went on to become a famous sculptor, one might dare to guess that the clay version was way cooler than the original.

Years later, Sachs is still making re-creations. The 46-year-old is regarded as champion of the sculpting form known as bricolage. At his New York studio, he and his team of loyal assistants use assorted nuts, bolts, tape, plywood, foam core, glue, and other easily procured materials to make replicas of objects—often, icons of daily life or capitalist culture—that look exactly like the real thing.

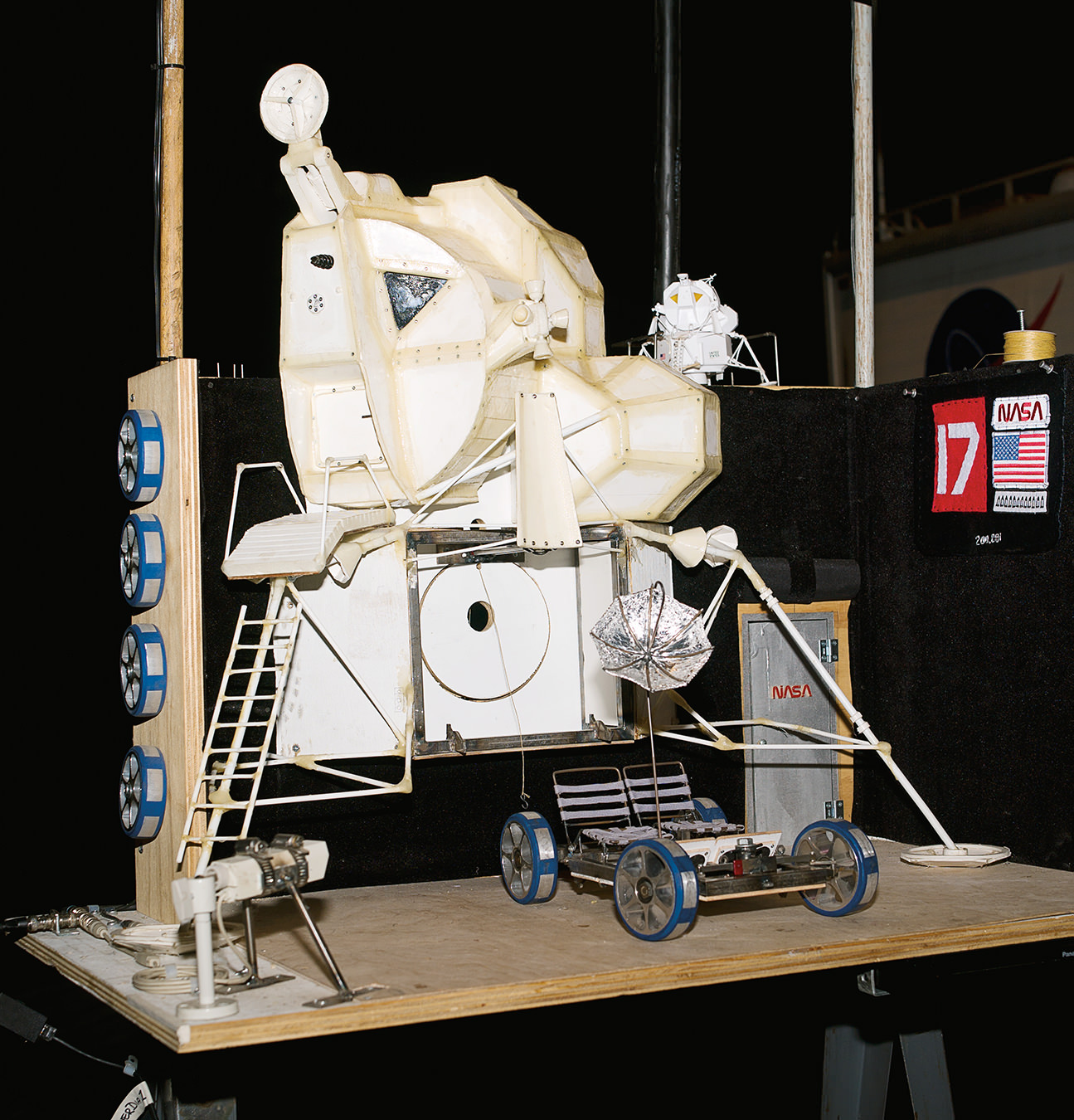

Details from Space Program: Mars at New York’s Park Avenue Armory. Sample Return, 2012.

And judging by his career so far, the man is pretty good at it. Sachs’s work can be found in prestigious institutions worldwide, including the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York; the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris; the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; and the Astrup Fearnley Museum of Modern Art in Oslo. What he makes, and the system by which he makes it, reflects not only Sachs himself, but a specific way of understanding the world through art. The work is often clever, meticulous, and subtly infused with humour of a deadpan sort.

Take, for instance, Sachs’s most recent coup, the interactive installation Space Program: Mars, in which the artist and his crew transformed New York’s Park Avenue Armory into a massive space station this past spring. The expansive exhibition was Sachs’s interpretation of the NASA Mars missions, re-conceptualizing and actualizing many of the objects used in these expeditions, including the Mars landscape, launch pads, mission control, and exploratory space vehicles. More significantly, as Sachs explained after the exhibit had closed, it remains a great example, or “source model”, of the very specific way he and his team build things in the studio and understand the world—and this applies not only to that particular exhibit but everything that came before and, likely, what will come after. He said, “We continue to make objects that celebrate the handmade, the personal, the identity of being human.”

As Sachs explained after the exhibit had closed, Space Program: Mars remains a great example, or “source model”, of the very specific way he and his team build things in the studio and understand the world.

At the Mars show’s star-studded opening party, shades of the red planet blended with retro Americana as waiters circulated with snacks and ladled specialty cocktails from steaming tureens. Some 2,000 guests wandered through the 55,000-square-foot Wade Thompson Drill Hall, oohing and aahing at meticulously reconstructed space program artifacts, more than 20 of them. There was the Mobile Quarantine Unit (MQU) (a refurbished 1972 Winnebago Brave); Mars Roving Vehicle (MRV) (a stripped-down go-kart-like apparatus made from a golf cart); a Japanese tea house, inspired by Robert H. Goddard’s launch control shack; and dozens of other pieces. Some offered a kooky wink, like the Vader Fridge, a Sub-Zero fridge cloaked in Darth Vader garb filled with mini cans of Budweiser—an essential requirement for colonization and survival up in the cosmic unknown.

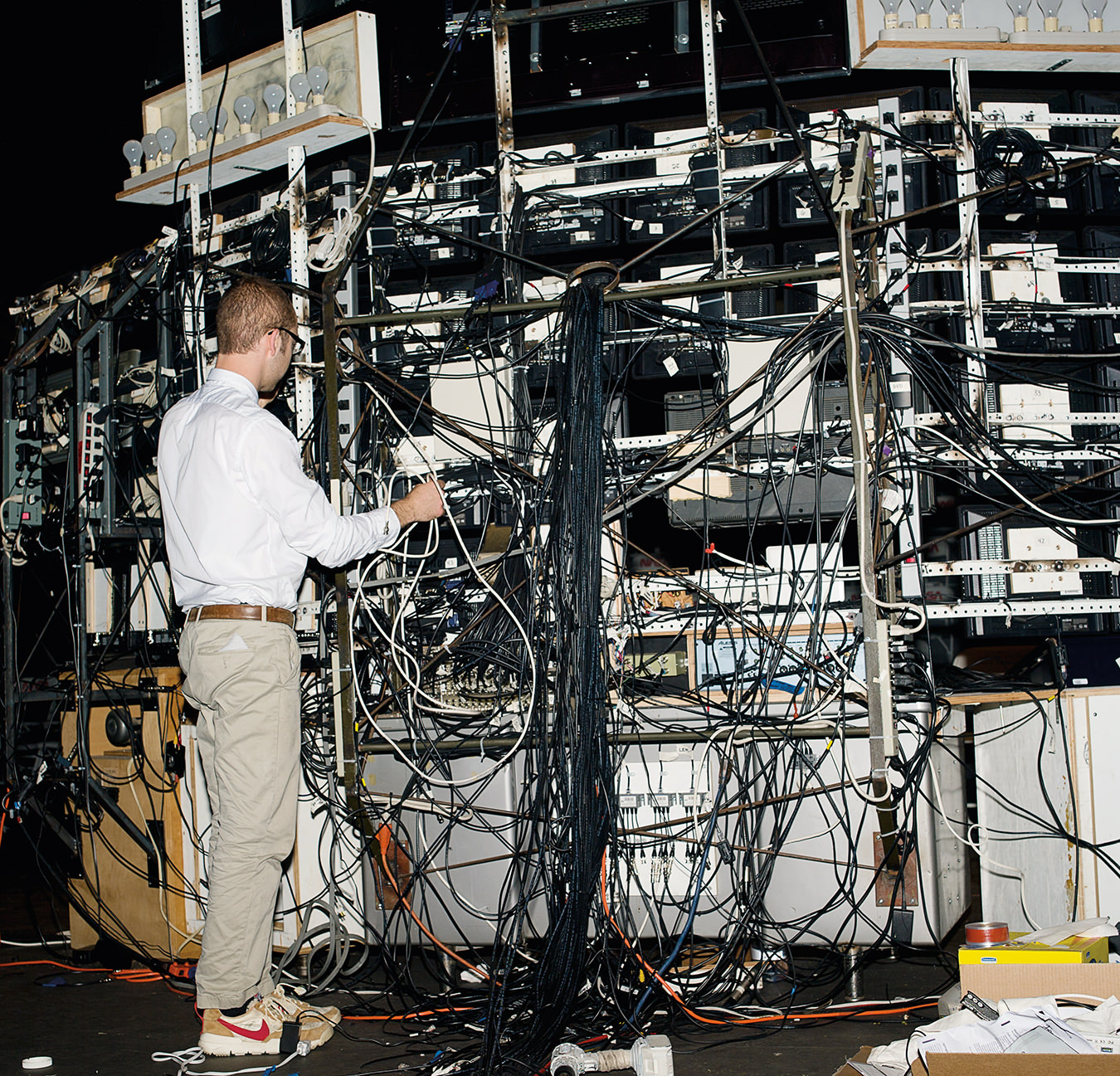

Armory for the War on Plywood (AFWOP), 2012.

“Tom Sachs’s work taps into the role of space flight in America and in the American psyche, particularly relevant given the recent grounding of the NASA Space Shuttle Program,” said Anne Pasternak, president and artistic director of Creative Time, who co-curated the exhibition alongside Park Avenue Armory’s consulting artistic director Kristy Edmunds. “Space Program: Mars explores the idea of space travel as a lens through which we can examine ourselves and our past, present, and future.”

“The work is both humorous and serious, giving viewers insight into the challenges of space travel, but also leaving us to ponder our place in the universe,” added Rebecca Robertson, president and executive producer of Park Avenue Armory.

The exhibition was sometimes serious, other times ironic, yet always ambitious, and the much-talked-about star had to be the 23-foot-high Landing Excursion Module (LEM). This life-sized re-creation of the Apollo Lunar Module space capsule was a bricolage replica of the actual module that NASA astronauts used to access the surface of the moon for mankind’s debut moonwalk.

“NASA is a very open institution with information sharing—a lot of stuff is public knowledge available to anyone,” said the bespectacled artist, looking very official in his white dress shirt and tie, breast pocket holding a bona fide pocket protector and a sole pen.

“There’s an ongoing dialogue with a number of scientists. They’re really jealous of us because we have all this freedom and permission. We just do what we want,” Sachs said. “They’re the ones who need professional approval for every little thing—which we ignore. What we can’t do with rocket fuel and titanium, we do with cardboard and hot glue.”

In a heavenly fusion of art and science, NASA logos popped up all over the place, and some of its experts even made appearances at Sachs’s space odyssey. Scientists from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory gave public talks at the show. And Buzz Aldrin, the astronaut who used the real Apollo Lunar Module in 1969 to become the second man to walk on the moon, visited the exhibit. Why not? After all, this was hardly Sachs’s first foray into the cosmos. His critically acclaimed 2007 Space Program mission to the moon showed at the Gagosian Gallery in Beverly Hills and was a similar re-creation of man’s first landing on the moon. And his mission this time around, for which he enlisted a team of 13 studio assistants, was as seriously real as real can be: to find life on Mars.

“It is a real mission,” he explained during the run of the show. “We really are going to Mars. The more seriously we take it, the more real it becomes for us. If we have condensation building up in our helmets as a result of it being airtight, it’s another layer of real, sort of like a martial artist who practises his whole life to become at one with his mind and his body.”

And in terms of Sachs’s overall approach, work ethic, and studio system, this is where things get even more interesting. From a certain perspective, it seems that in Tom Sachs’s cloned universe, the line between “real” and “not real” disappears into the horizon. Which, for the rest of us humans, posits larger questions: What is real, anyway? And who decides?

Mission Control Center (MCC), 2007.

“Let me tell you the story more,” he said. “The martial artist is confronted by muggers in a dark alley and is about to use his martial arts on them, but because he has such mastery of his body, he disabled them with words and he walked away and they walked away. Later, on his deathbed, he realized he never threw a punch in combat. All he did was train for combat, and he dies knowing he spent his life as a student.”

Sachs was born in Manhattan and grew up in Connecticut. He studied at the Architectural Association School of Architecture in London and earned his BA from Vermont’s Bennington College in 1989. The following year, he moved to New York, where, at one point, he worked as a welder. In 1994 his Hello Kitty Nativity caused quite a stir, as did Hermès Hand Grenade the following year, and both earned the young artist an international reputation for their implied statements on fashion, violence, and the commodification thereof; these were followed by the Chanel Guillotine (Breakfast Nook) in 1998. In addition to the museum collections, Sachs has had major solo exhibitions everywhere from Fondazione Prada Milan to the Deutsche Guggenheim. Galleries he works with include Sperone Westwater, Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, and Baldwin Gallery.

Which brings us back to Sachs’s process, his way of seeing the world and making stuff in the studio. The term “transparency” often pops up when describing the artist’s body of work. Translation: the process is evident in (and part of) the result. The steps and seams, screws and stitches, bricks and mortar, glue and guts, can be seen within each piece, exposed for the viewer to experience and be part of.

Reflecting this concept, Space Program: Mars was very inclusive, offering sincere opportunities for audience participation. “We have a whole indoctrination program here for those people from the public who want to be part of us,” Sachs said excitedly during the exhibition. “We have a way! You can come help us sort screws, and work your way up the corporate ladder to Mars.”

On Mars, getting involved meant dropping by the aptly named Indoctrination Station for a quiz. The questions were based on five short films that visitors were invited to watch as part of the indoctrination process, either in the onsite theatre (popcorn cost $1) or online at TenBullets.com. If you scored high enough, you earned the right to enter and explore the Landing Excursion Module (LEM). (And, if you were lucky, find the cigarettes hidden inside. Yes, astronauts like to smoke. They also enjoy cocktails, as indicated by the many booze bottles nestled in various vehicles.) A successful indoctrination also allowed a visitor to sort screws and sweep.

The aforementioned crew of 13 studio assistants were somewhat exposed, too. For the duration of the exhibit, they and Sachs took up residence at the Armory in order to better execute their mission. Clad in Prada lab coats over hipster attire, and Grumman uniforms by J.Crew, these artists-turned-space-cowboys could be seen skateboarding around the space, answering questions, preparing and eating meals, and performing scheduled Public Demonstrations at Mission Control—a wall of 54 Sony screens that told the story of the exhibition, showing live feeds of all the special effects throughout the show, punctuated by an applause sign.

At one point, for example, an assistant hopped on his skateboard and zoomed over to a compact cooking unit, Red Beans and Rice (RBR), nostalgically reminiscent of The Jetsons, or perhaps those first Easy-Bake ovens. He withdrew from the oven a steaming plate, popped a wheelie, and zoomed over to the stadium-seating bleachers that flanked the great Drill Hall. Work is another key element of Sachs’s pragmatic ideology and meticulous system of getting things done. So much so, in fact, that “Work” was the title of his 2011 exhibit at Sperone Westwater in New York, his third solo show for that gallery.

Work the noun, as opposed to the show, includes deceptively minute tasks like sorting screws, sweeping, and other show-specific rituals. In all cases, these tasks may seem simple, yet they are protocol and key to the team’s success as a unit. Whether they’re blasting off to Mars or building other stuff in the studio, each task must be completed just so. Which is just the way Sachs likes it.

The term “transparency” often pops up when describing the artist’s body of work. Translation: the process is evident in (and part of) the result.

This entire philosophy (or perhaps ideology is a more appropriate word) is captured in a series of films that are also stand-alone works (for view on YouTube) titled Ten Bullets, Color, How to Sweep, Love Letter to Plywood, and Space Camp. And the films are very important. So much so, in fact, that Sachs wouldn’t do interviews with reporters who hadn’t seen them—and rightfully so. After viewing the films, one appreciates Sachs’s efficient perspective. These deadpan corporate instruction videos define the techniques, rules, systems, and overall vibe of Sachs studio culture. Directed by the charming artist Van Neistat (who also shot a new film at Space Program: Mars), it’s hard to tell whether the flicks are serious or satirical. Probably both: brilliant and hilarious—kind of like The Office meets The Jetsons and joins the military.

Their absurdist, propaganda-like encouragement of conformity, systems, and efficiency becomes a portal into Sachs’s systematic studio approach. One realizes that the artist behind this whole operation is also a strict ringmaster and systems builder. To get into it is to surrender to a parallel universe of intricate systems required to actually build any exhibit of such massive scope, and to keep it running smoothly. One may consider conformity to be the antithesis of creativity, but in Sachs’s ordered chaos, it gets things done. And there is always a lot to do. That’s why productivity and efficiency lie in discipline and ritual.

“You can kind of understand how Ten Bullets and Color and How to Sweep are the foundation for how we build things in the studio,” he explained. “It’s just the way we try to keep things together when we have such an elaborate system that we try to keep pushing forward … It’s not the only choice, it’s really not the right way, the wrong way, or your way—but it is my way.”

Fair enough.

So what’s next? Sachs’s studio has been in talks with the Baldwin Gallery in Aspen about a winter exhibit, scheduled to open in December. Van Neistat’s new film is also coming out soon. And with Mars checked off the list, Sachs has set his sights on possibly landing on other celestial bodies. “We’re looking at Europa, which is the icy moon of Jupiter filled with liquid water, so that’s pretty exciting,” he said.

Ultimately, whatever the piece, exhibit, or system, the work is united by an exploration of what it means to be human. This means a viewer experience that consistently probes the imagination with playful nostalgia and futuristic aspirations, tapping into humanity’s curiosity to ponder the mysteries of the universe and eternity so we are once again teenagers, lying on our backs and staring at the stars.

“I think science and religion are on a parallel course to answer the same unanswerable questions,” Sachs said. “Where do we come from and are we alone? [So far] it’s inconclusive, because although you might be able to find some evidence of life [on other planets], or evidence of the kind of environment that can support life—small microbial things—the interesting thing is how it could evolve into intelligent life. So we don’t really know. Maybe it’s the past or potential future of intelligent life. But there are some signs.”

_______

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter here.