Squamish and Lil’wat Nation Artists Celebrate Tradition and Lift Modern Art

The carriages on the Peak 2 Peak gondola act as outdoor art installation, presenting First Nations art in a unique way.

What does it mean to represent your culture? There is no easy answer. Artists, poets, singers and ordinary people have grappled with the question forever. If what we do is the product of where we come from, with all the diversity and nuance that involves, it becomes obvious that expressing oneself, in whatever form that takes, is the truest representation of a culture because it comes from the most important part of it: the people. For cultures as old and as rich in history as the Squamish and Lil’wat Nations, there is the added pressure of maintaining, respecting, and honouring centuries-old practices while keeping pace with the modern world.

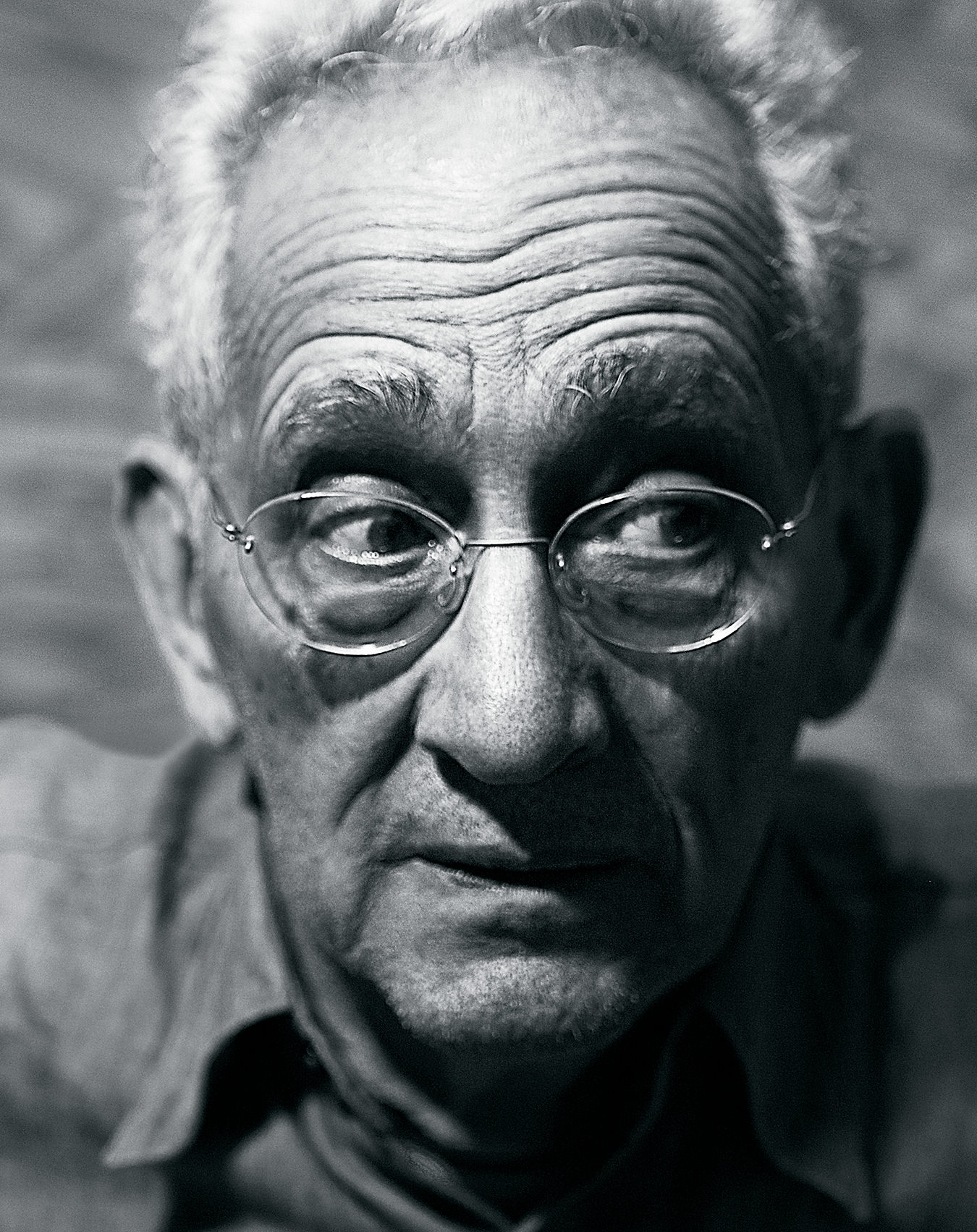

“I think I’m still connected to the ancient traditional values of it. But they’re filtered through my new brain,” says artist Levi Nelson. He is discussing his painting Red and in particular its use in the Gondola Gallery by Epic at Whistler Blackcomb. Organized by Vail Resorts, the Gondola Gallery is “an outdoor art installation and film series that celebrates the unique backgrounds of skiers and snowboarders.” The first two installations—Uplifted by Lamont Joseph White in Park City and Creating Your Line by Jim Harris—debuted late last year, and now Nelson’s contribution has been revealed.

Nelson, a member of the Lil’wat Nation, grew up near Pemberton and, after attending art school at Emily Carr in Vancouver, went on to study at Columbia University in New York. When he was approached about participating in the Gondola Gallery, Nelson says he almost said no because he was so busy. He did, in the end, agree, and the result is Red, which adorns the outside of one of the carriages on the Peak 2 Peak gondola connecting Whistler and Blackcomb Mountains. Nelson is a contemporary visual artist, and his work for the gondola is a confluence of his “ancient traditional values” and “new brain,” a piece that situates Lil’wat symbols and style within a contemporary visual aesthetic.

“When you think about the shapes here like the trigon on the crescent, the use of the ovoid, these are specific to my Indigenous culture. And then on the flip side of that, we have Western geometry—the triangle, the circle, the square—so you see that they both, at the end of the day, make up the world around us but in different ways,” he says. Nelson’s striking painting Red hangs on the wall of the Skw̲xw̲ú7mesh Líl̓wat7úl Cultural Centre.

In 2001, the Lil’wat and Squamish Nations signed a historic Protocol Agreement, to this day the only one of its kind in Canada. The result was the “continued cooperation in matters of cultural and economic development and co-management of shared territory.” As part of this agreement the Squamish Lil’wat Cultural Centre was born, and when it came time for Whistler’s gondolas to join the gallery, it was important to include work from both of these Nations, on whose unceded territory the resort lies.

While Nelson’s contemporary art updates old symbols for a modern eye, Chepximiya Siyam’ Janice George and Skwetsimeltxw Willard (Buddy) Joseph are helping maintain and revive an ancient practice once at risk of disappearing: Coast Salish wool weaving.

George, a hereditary Squamish chief, is a museum curator by training, and Joseph was director of Hiy̓ám̓ Housing and Planning & Capital Projects. Both have found a second passion since being taught the patterns and techniques of Salish weaving. They took up the practice in the early 2000s, learning from a mentor after a chance meeting. Learning to weave was about more than just the skill however, it was about reviving a lost art, one that is deeply connected to their ancestors. George says, “When we went to learn, we knew that Vancouver was bidding for the Olympics. And I was worried about how are we going to represent ourselves? We had no weavers, you know? What were we going to do to help people understand that the Coast Salish, we have traditions, and that our ancestors were brilliant, and they made beautiful things?”

Some 14 years have passed since those Olympics, and in the time since, the pair estimate they have passed on the skills they were taught to 3,000 pupils. “To be able to learn it, and then feel the urgency to teach it was just, it was like being shot out of a cannon,” George says. After all they have done to resurrect and pass on the skill, it was only natural that the duo should produce one of the artworks when the Gondola Gallery by Epic came to Whistler.

Their design, Wings of Thunder, is the embodiment not only of what they have learned but also of what they know about the history of the land Whistler Blackcomb now occupies. The geometric design centres on the thunderbird. “The colours represent the power of the thunderbird, a grandfather figure who cares for the Squamish people, and spirituality of the ancestors,” George says. “Our hope is that guests feel inspired by the Squamish history, art, and design that is alive and well today.”

Working on the design was a collaboration between. “My background is construction,” Joseph says. “So it’s all mathematical and calculations. Janice’s background is in art history, museum studies, fashion design. When we collaborate on a piece, I’d say it’s very spiritual as well. Coming together pretty quick, figuring out the colours. Everything about it [the piece] tells the story. Great colours on the gondola talk to me, tell the story about the piece.”

As magnificent as it is, Wings of Thunder is not the culmination for George and Joseph. Even after all they have done, Joseph says, “I can only talk about urgency. I still feel that way too, that we need to reach as many people as we can. We’re still teaching.” More than anything, the gondola is another chance for visibility, a highly visited, extremely visible beacon on the biggest ski resort in North America. George and Joseph have done more than most of us can achieve in one lifetime, and still they see how important it is to preserve and grow their traditions, and remind visitors that before there was a mountain resort, there was a mountain.

At the peak of Whistler, looking across at The Black Tusk, the home of the thunderbird and a landmark older than memory, whilst surrounded by the modernity of a ski resort, it is hard not to see the threads of it all. Trends, designs, and fashion come and go, but the mountain will always be there inspiring whoever looks up at its peak. All we can do is hope to pass on some understanding of what came before.

“That thunderbird roost is part of the land,” George says. “How are we going to take care of that? How are we going to regard that? Everything we do, I think about those ancestors up there, those chiefs that took care of this place. I will say every time I look out my window and look at my door, ‘I see the work that they’ve done for me. Everything we have is because of them. How do we honour them?’ And that’s part of what I wanted to do.”