The Obscure Champion of Francophone Writing Who Called for Canada to Join the U.S.

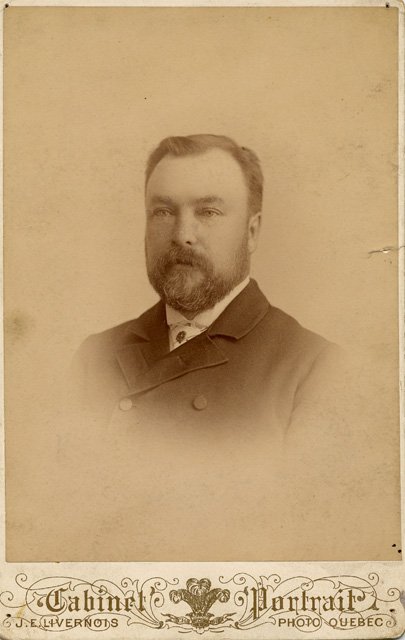

Prosper Bender.

Louis-Prosper Bender [ca. 1880], Fonds J. E. Livernois Ltée, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, P560,S2,D1,P16.

In 1908, a Boston homeopathic journal noted the death of one Prosper Bender. It read: “Enquiries made at the hotel where he had an office for many years give the reply that Dr. Prosper Bender is dead. No particulars.” How odd a feeling this must have been for Bender, who was, in fact, alive. How peculiar to experience first the uncanny exposure to a world in which one is dead, and second, the realization that no one thought to look more closely. For Bender had simply gone back to Canada, to Quebec City, the place of his birth and upbringing.

Bender’s premature death announcement in some ways prefigures his eventual eclipse in the history of Canadian imagination. In his time—at least toward the beginning—Bender was a shining star of the Eastern Canadian literary scene. He was a refined man who claimed Joseph-François Perrault as a great grandfather and promoted French-language literature in an attempt to bridge the cultural divide festering between French and English Canada.

Bender’s premature death announcement in some ways prefigures his eventual eclipse in the history of Canadian imagination.

Patrick Lacroix, a historian of Canada, who has brought Bender out of obscurity, writes that Bender was an “intercultural broker” who “challenged the appeals of nativists and ‘fanatics'” at a time when the history of Canada was uncertain. But like history itself, Bender’s opinions on his home nation would change.

By Lacroix’s account, Bender was a worldly man, which certainly made him more complicated. The son of a Québécois attorney and an Irish immigrant, Bender pursued medicine and liberal arts, before eventually having his medical licence revoked for practising homeopathy. He joined the Union Army in the American Civil War as a surgeon. After returning home, he became a nexus of the thriving literary scene in Quebec City during the 1870s, publishing a compendium of francophone writing in English in an attempt to promote the literature of his friends and beloved local writers across the language gap. Bender was in a position to become a model for those who wanted to celebrate both the unique culture of Quebec and the potential for a flourishing future under Confederation.

But then things shifted. Many of Bender’s literary friends gained positions in the new government, and Bender moved to Boston. Lacroix notes that the exact reasons for his move are unclear—but it followed a trend of many Quebecers moving to the American New England for work in the booming industrial sector. Bender set up a medical practice in Boston, and seeing the growth in the American economic atmosphere, became disillusioned with the Canadian project. Bender embraced annexationism (a fringe belief that held Canada should be annexed by the United States), penning articles like “The Disintegration of Canada.” These articles eroded his position of renown in the Canadian literary circles.

If anything, these changes reflect a life of deep thought and an open mind, something that many with fixed opinions could take note of.

Bender lived in Boston for 25 years, but despite his essays, it became clear he was not finished with Canada and soon softened in his views. He eventually moved back to Quebec, where he died in 1917. His faith revived as Canada’s narratives kept it going into the long 20th century. Perhaps it was his changing opinions that led to Bender’s obscurity and minimized role in the intellectual canon of the early nation. If anything, these changes reflect a life of deep thought and an open mind, something that many with fixed opinions could take note of. Lacroix insists that we can learn something from Bender, writing, “Within 20 years of the British North America Act, Bender had given some of the clearest expressions of confidence and doubt in Canada’s nation-building process. Even in doubt, he continued to represent French Canadians and their culture among their neighbours.”

________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter here.