Experiment & Elegance: Paolo Ferrari Designs the Stuff of Dreams

From deep time to outer space.

In the opening scene of Stanley Kubrick’s film 2001: A Space Odyssey, early hominids thrash about on a plain coloured by the orange sun of an eternal primeval sunset. After a sequence of the figures hooting and dancing around a dark, probably extraterrestrial monolith of mysterious origin, the scene cuts to an individual picking up a bone and discovering the femur can be used to extend its power and bash things. The final frame shows the victorious tool-wielder throwing the bone in the air, where it spirals and falls to the earth. The screen then cuts to the revolving form of the Discovery One spacecraft spiralling in orbit, signalling the evolution of tools from the simple reuse of the organic objects to the ultrasynthetic space-faring vessel.

From the distant past to the distant future, the object in frame creates a metaphoric lineage but also a collage: the past and the future existing simultaneously in the clean lines of the bones, in the spacecraft, in the present. It is on this fracture, this imaginative space where the past and the future intersect in the familiar material of flesh and bone that the work of architect and interior designer Paolo Ferrari operates.

Known for furniture and interior architecture, Ferrari has quickly become one of the preeminent young designers in Canada, attracting clients from all over the world with an aesthetic that, like the shape of the bone, transcends time and space, adjusting to a variety of functions and locations. The bone has roots in biologic and organic form, but after its primary use can become ornamental, can outlive its original purpose to take on new forms. This imaginative coming-to-life of material has defined Ferrari’s trajectory as a designer.

Quick to talk openly about process and concepts, Ferrari receives my call from his Toronto studio as we reenter pandemic restrictions in late 2021. Having spent nearly two years living in the pandemic makes speech more candid, and as we discuss film and his inspiration, Ferrari is forthcoming. You can tell from how he talks about his projects that conversations are essential to the way his designs come to life.

Ferrari’s story starts out like so many designers in Canada: a youthful exposure to the crafts of countries of origin mixed with North American dynamism and need for experimentation. Yet Ferrari stands out in his ability to shift colour schemes and material allegiances from project to project without relying too much on unifying visual cues. Canadian design, so often literal and graphic, is twisted and exposed to an almost surrealist glamour under Ferrari’s uncanny sensibility. The styles of the past and the dreams of the future animate Ferrari’s story and his practice.

The staircase in a recently designed hotel spirals upward in an organic fashion. Photo courtesy of Paolo Ferrari Studio.

Ferrari’s father grew up in Italy before first coming to Toronto in the 1960s, disliking it and leaving, then eventually returning to the Canadian metropolis in the late ’70s with Paolo’s mother and his older brother. Paolo was born shortly afterward. His father was a furniture maker, exposing Ferrari to craft and design early on. A close family friend worked as a seamstress in a shop that made leather garments, introducing him to the relationship between bodies and materials, scale, and function—but also to the creative play that comes with having a mass of materials at your fingertips. “I had the freedom of creation and had access to leather or wood and these things that as a child maybe you shouldn’t be playing with,” he laughs.

This sense of play, mixed with a youthful drive to break rules, has followed Ferrari through his career, from his time at OCAD studying environmental design to his years working under renowned Canadian design firm Yabu Pushelberg. Ferrari broke off into his own studio in 2016, where he began developing furniture and designs using highly conceptual objectives. Here, Ferrari has broken the mould again and again, relying on his imaginative tendencies to create one-of-a-kind works for clients.

“This idea of trying to start from a very abstract point is something I find quite exciting and quite rewarding,” he says, mentioning film as a place he goes again and again to find the seed ideas that blossom into projects of epic proportions. In our conversation and in prior interviews, he has mentioned the aesthetic influence of film on his work repeatedly, not shy about his debt to Kubrick and David Lynch. The input of the futuristic and the uncanny is unmistakable in projects such as the Toronto cannabis dispensary Alchemy, as well as his work on lounges in the emergent techno-cities of the Persian Gulf. But the gesture toward the conceptual is always tempered by a commitment to the earthy, to the anthropomorphic. This ambiguity between past and future, dream and reality places Ferarri’s work within the broad but exciting future primitive category, a trajectory of design that mixes the fantasies of the future with the traces of the past, allowing the work to be guided by elemental concepts and fictional directions.

“It’s all guided by a tight conceptual idea that we had,” he says of his design process. “And having those [conceptual] guardrails allows us to really take some risks because we can justify what we were doing against an abstract starting point. So it’s not just pastiche or a bunch of stuff melding together, it’s all anchored by an overarching idea [that gives us] freedom to take risks, experiment, and move beyond.”

It’s not often that someone so early in their practice is able to commit to such a robust experimental approach. Studio Paolo Ferrari turned heads early on with collections of furniture pieces that utilize thick shapes and plush fabrics that display both a tubular, space-age aesthetic as well as smooth materials of wood and white stone that signal a biomorphic aspect of the work. But the designs are not limited to following the colours of natural material, both in furniture design and in the interior projects.

If design history didn’t exist, “we’d be designing with this kind of anthropomorphic sentiment, which I think is natural because we’re referencing the world around us,” he says. “We’re referencing ourselves. We’re referencing the animal world.” Continuing, he explains that the underlying themes of the work are a desire to inspire awe and to get at a sense of the sublime that rests partly outside of what has been typical in the European canon of the last 200 years or so. It’s important to think beyond the strictures of tradition that we all have to operate in and use the multiple exposures and influences that come with the digital age in our work. “Because of all the access to everything, we’re exposed to so much, and to express something that is actually awe inspiring or that evokes the sublime is harder today than it ever has been,” Ferrari reflects.

_________

Canadian design, so often literal and graphic, is twisted and exposed to an almost surrealist glamour under Paolo Ferrari’s uncanny sensibility.

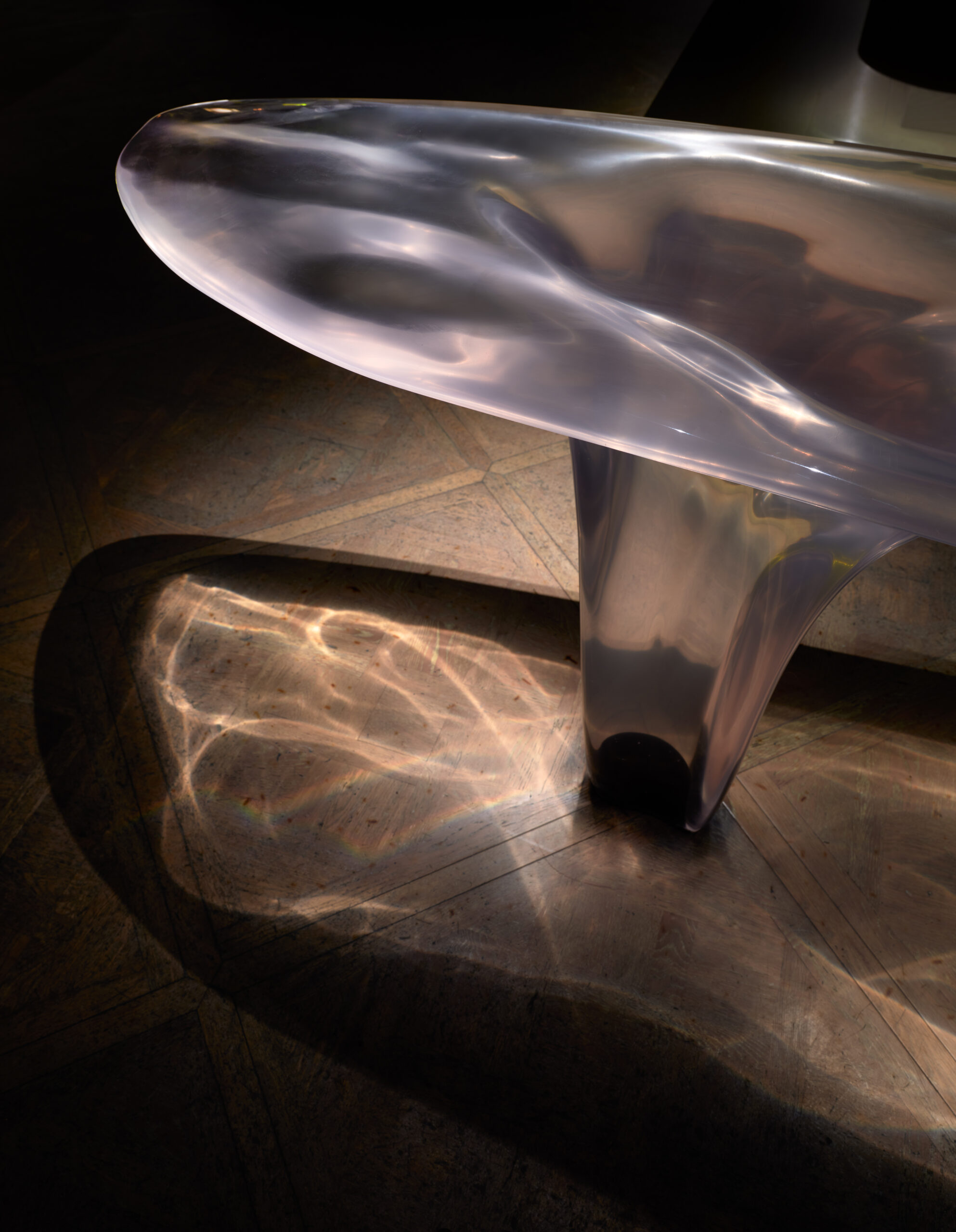

Secret Room, a bar accessible through a hidden passage under the majestic Five Palm Jumeirah Hotel in Dubai. Photo by Virgile Simon Bertrand.

Photo by Virgile Simon Bertrand.

But the work of his studio, which has grown to a practice of 20 people, still manages to evoke wonder and even surprise. Take the design for Secret Room, a bar accessible through a hidden passage under the magisterial Five Palm Jumeirah Hotel in Dubai. Taking influence from the plush geometrics of Pierre Paulin, the splendour of a grand villa, and the dream aesthetics of Dali, the space is dominated by a central bar. The bar is sculptural, with a plastic sense of movement that makes it seem molten, alive, like a manifestation of living quicksilver taking form, a sensation of plastic motion that is continued in the other tables and lounge areas in the radiating spaces. On the other hand, ornate walls printed to appear like fading frescoes and detailed crown moldings evoke old Europe, contrasting with the futuristic.

Photo by Virgile Simon Bertrand.

Photo by Virgile Simon Bertrand.

“I do believe there is something so powerful in the physicality of what we do. We are of the mindset that a great project can be an entire world within itself,” Ferrari says of the bold forms. According to the designer, the Secret Room is meant to feel indulgent while simultaneously ancient, to evoke a tension of eras, and make visitors ask, are we in 1900 or the year 2500? This weirdness makes the designs seem perennial, outside the tastes of the present moment, and since tastes are changing so quickly, creating these environments seems a proper way to ensure a design is enduring.

Another instance of Ferrari pursuing the dream space is the recent design of Alchemy. The materials of the interior reflect the cinematic sensibilities of David Lynch, moving from gorgeous terrazzo to bright, graphic, modern spaces to a plush red room. Alchemy demonstrates both Ferrari’s range of clients and his commitment to the conceptual world of film.

_________

“We are of the mindset that a great project can be an entire world within itself.” —Paolo Ferrari

“For us, these projects become site-specific works,” Ferrari says of the different projects. “We’re pulling from distinct cultural references with the aim to create global destinations that feel authentic and appropriate. It’s all extraordinarily rewarding. There is also a lot of risk, as we’re often managing a great deal of complexity, and often these projects tend to be high pressure, but ultimately, with the right client, the result can be extraordinary.”

With the influence of film, the results are genuinely individual, and Ferrari manages to bring a host of familiar references to the table without falling into the trap many designers do today: nostalgia. Ferrari manages to wield references and materials in a way that does not rely on the forms of the past, and for that, and in the international reach of his oeuvre, he can truly be called an experimenter, populating the realm of architectural dreams that should and will be the backdrop for a generation of creatives.