-

James Cameron. Photo ©Mark Thiessen/National Geographic.

-

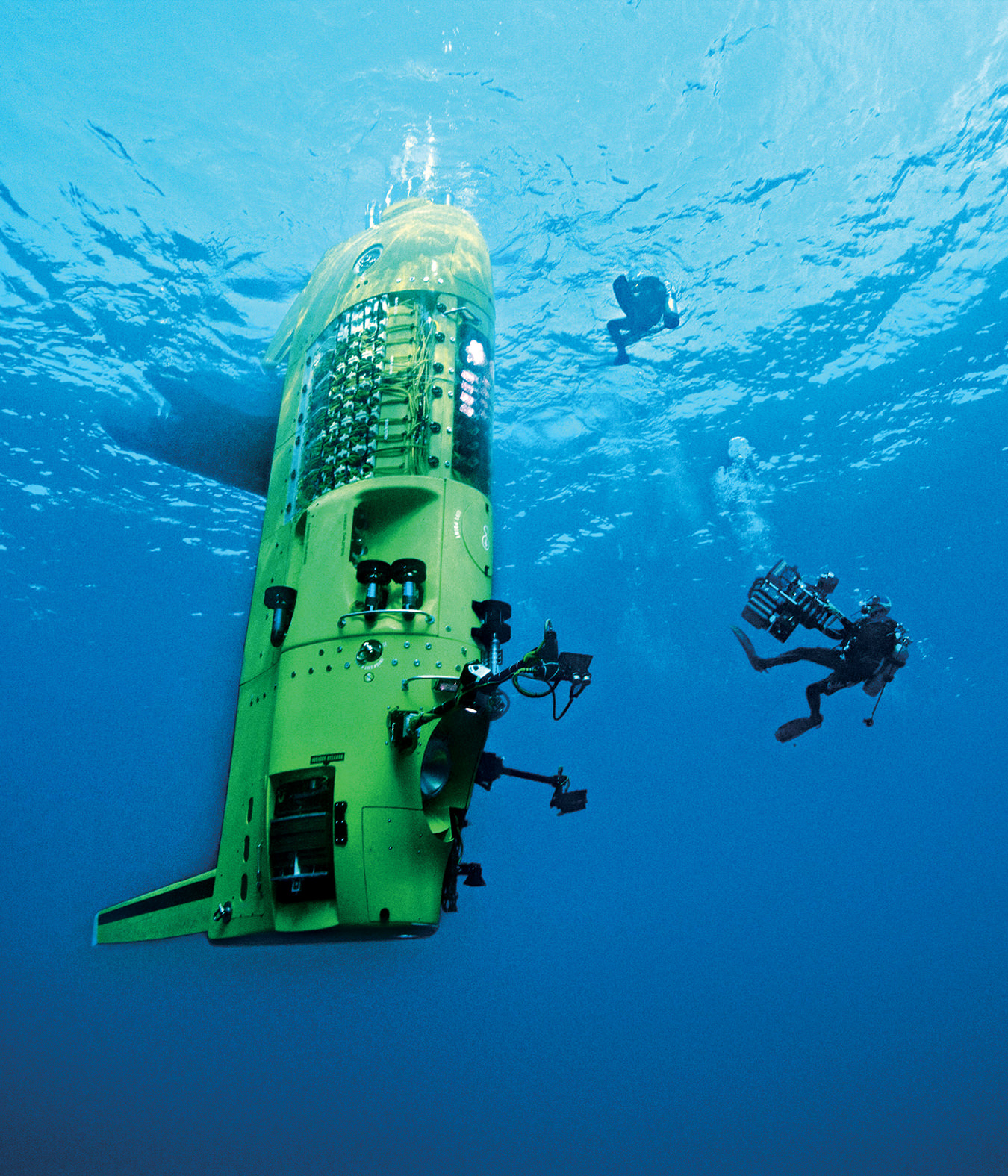

The Deepsea Challenger. Photo ©Mark Thiessen/National Geographic.

-

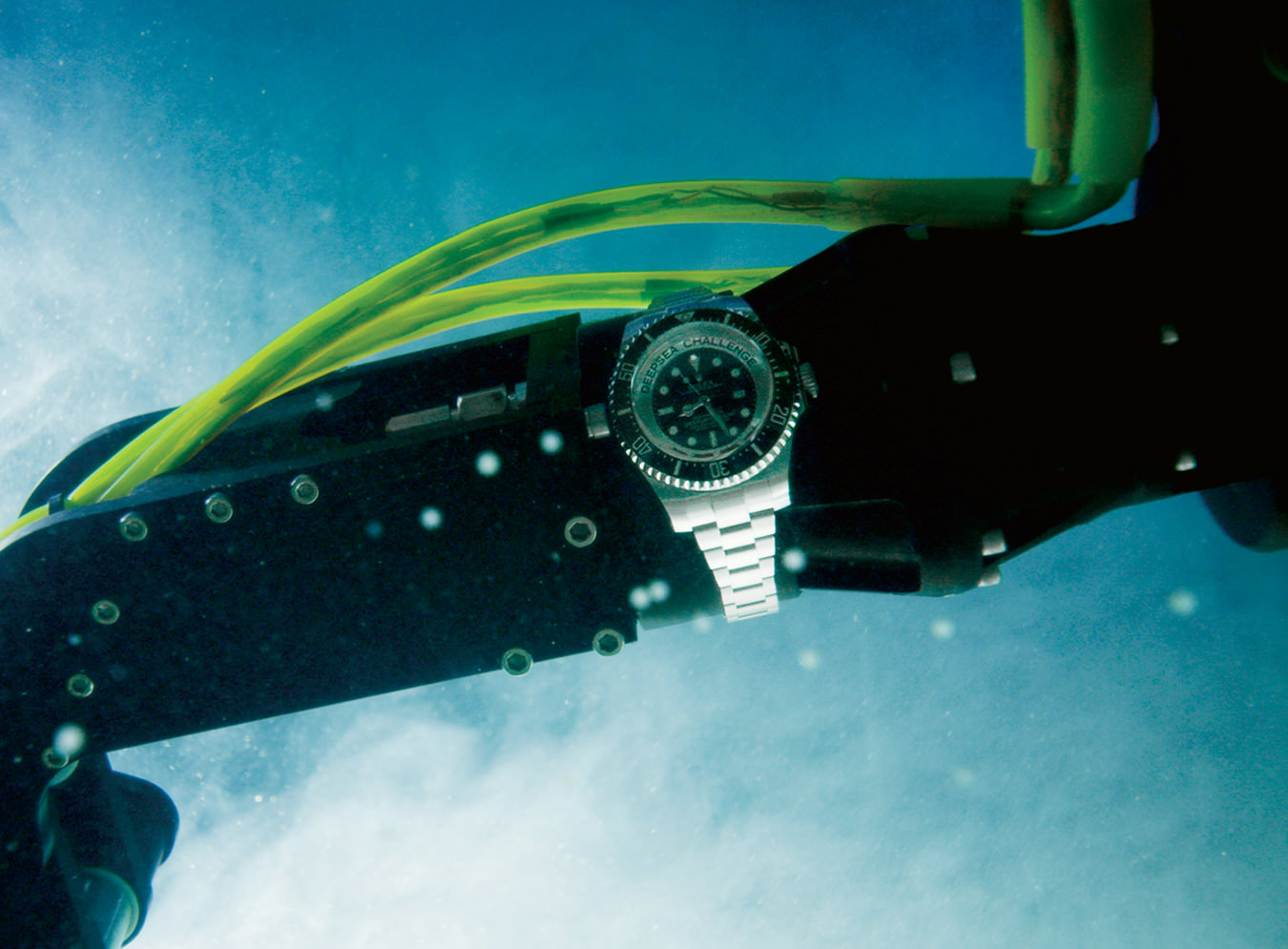

An experimental Rolex Deepsea Challenge wristwatch. Photo ©Great Wight Productions Pty Ltd/Earthship Productions, Inc.

-

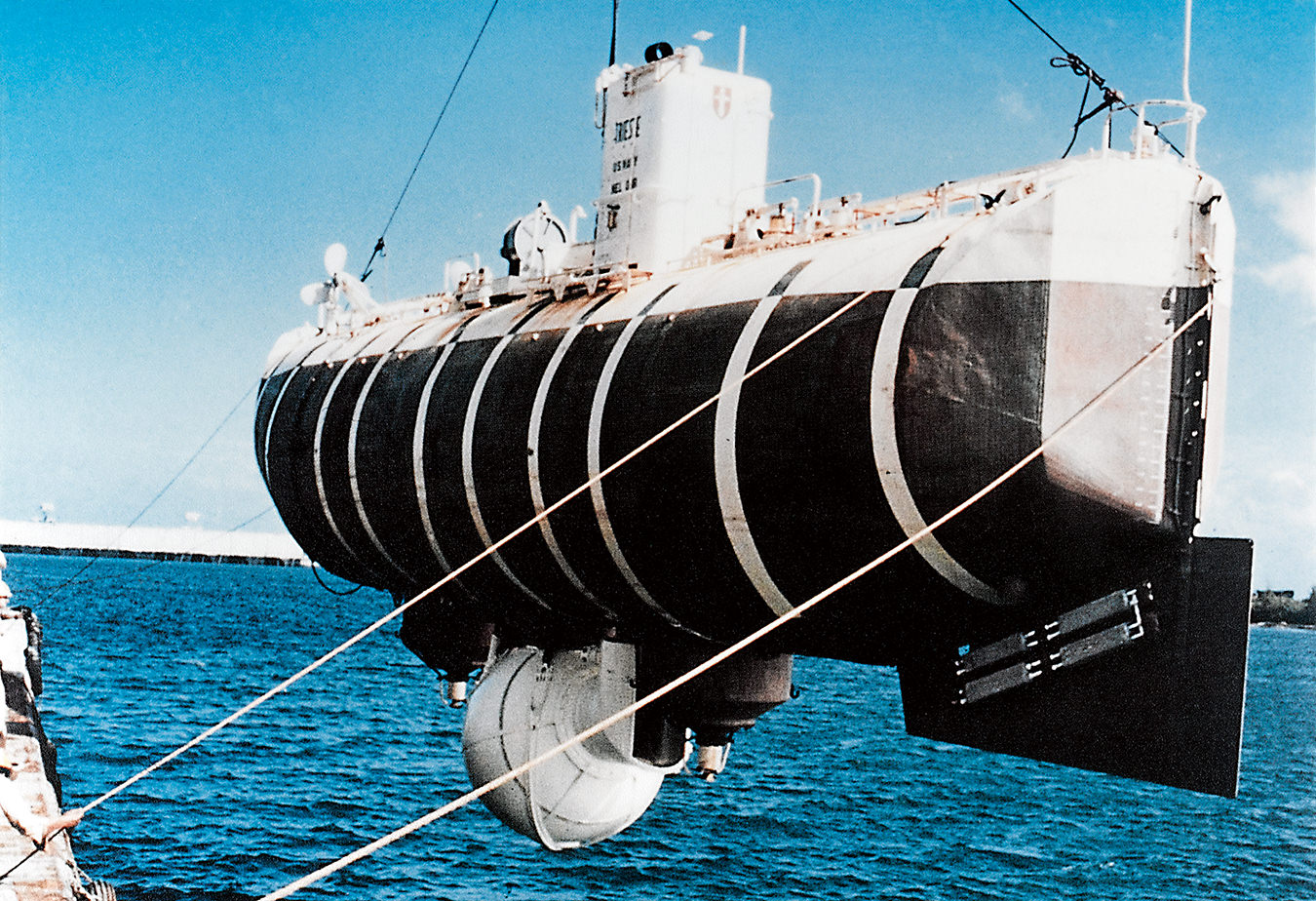

The Bathyscaphe Trieste, 1960. Photo ©Rolex.

-

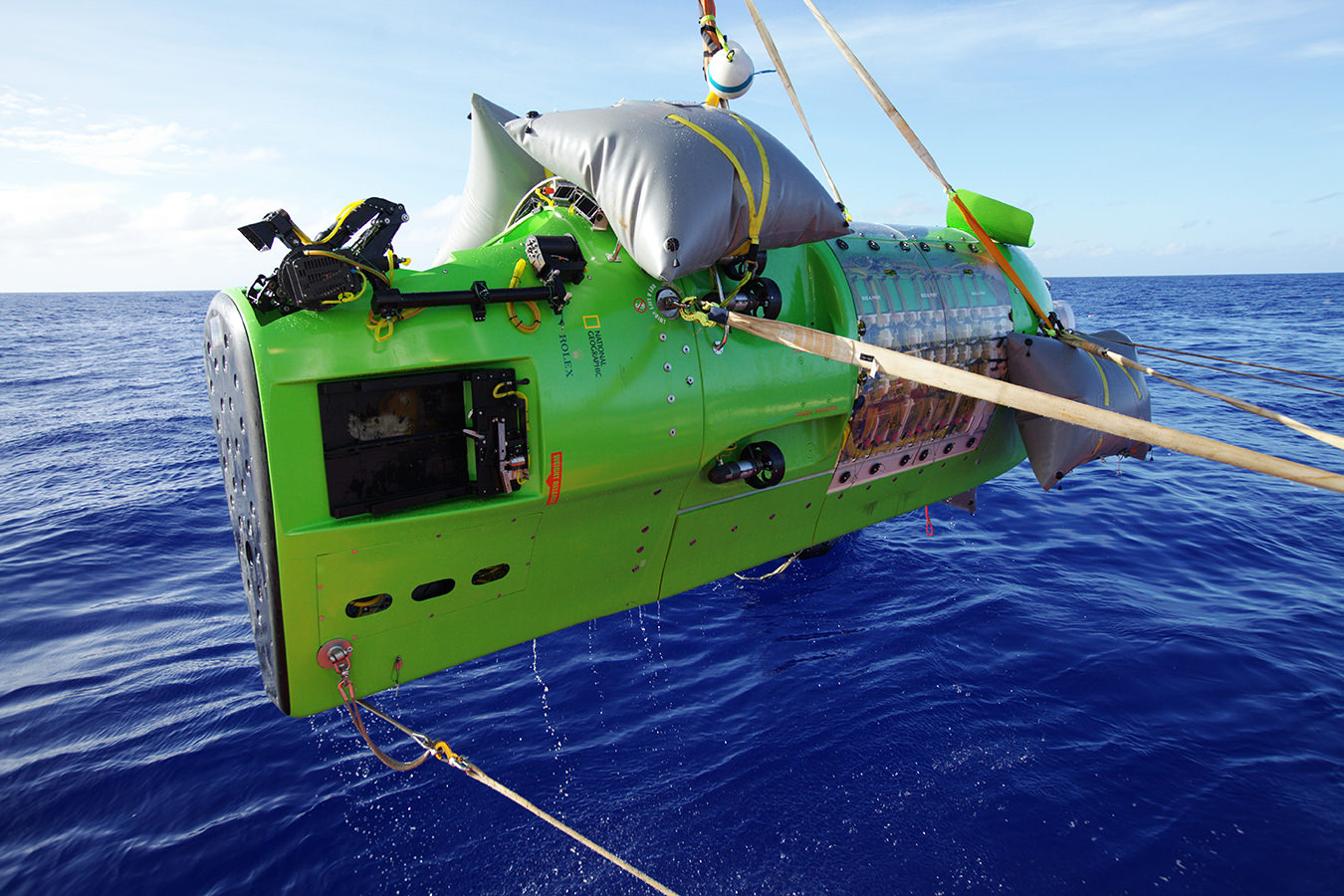

The Deepsea Challenger. Photo ©Mark Thiessen/National Geographic.

-

The Trieste surfacing after reaching the record depth of 10,916 metres in 1960. Photo ©National Geographic/Getty Images.

-

The Deepsea Challenger immersed in the ocean. Photo ©Deepsea Challenge/National Geographic.

-

The Rolex Deepsea divers’ watch for extreme depths, equipped with a “D-blue” dial. Photo ©Rolex/Alain Costa.

-

Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay wore a 1953 Rolex Oyster Perpetual on the

summit of Everest. Photo ©Rolex. -

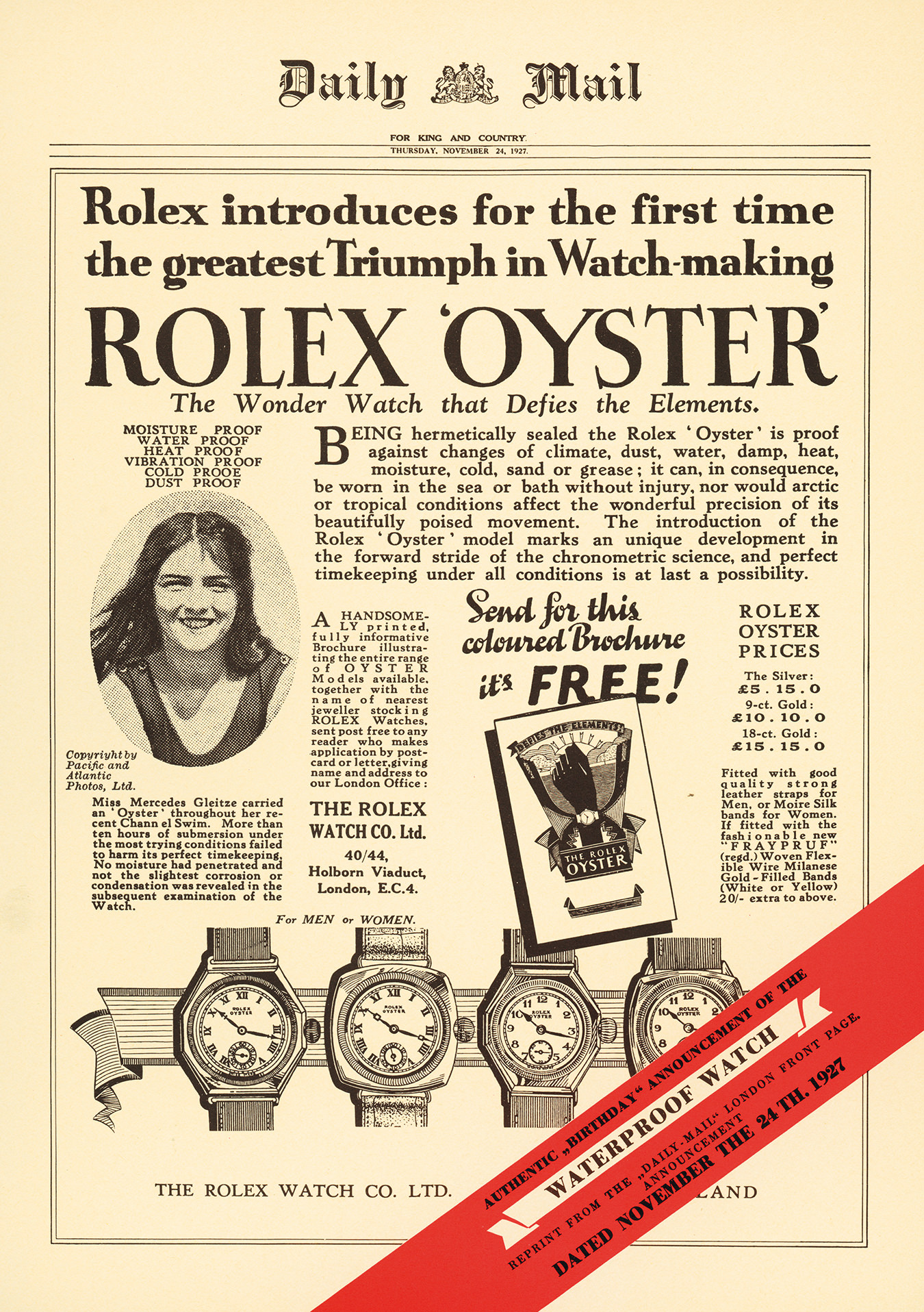

Daily Mail, 1927. Photo ©Rolex.

-

1953 Rolex Oyster Perpetual. Photo ©Rolex/Jean-Daniel Meyer.

-

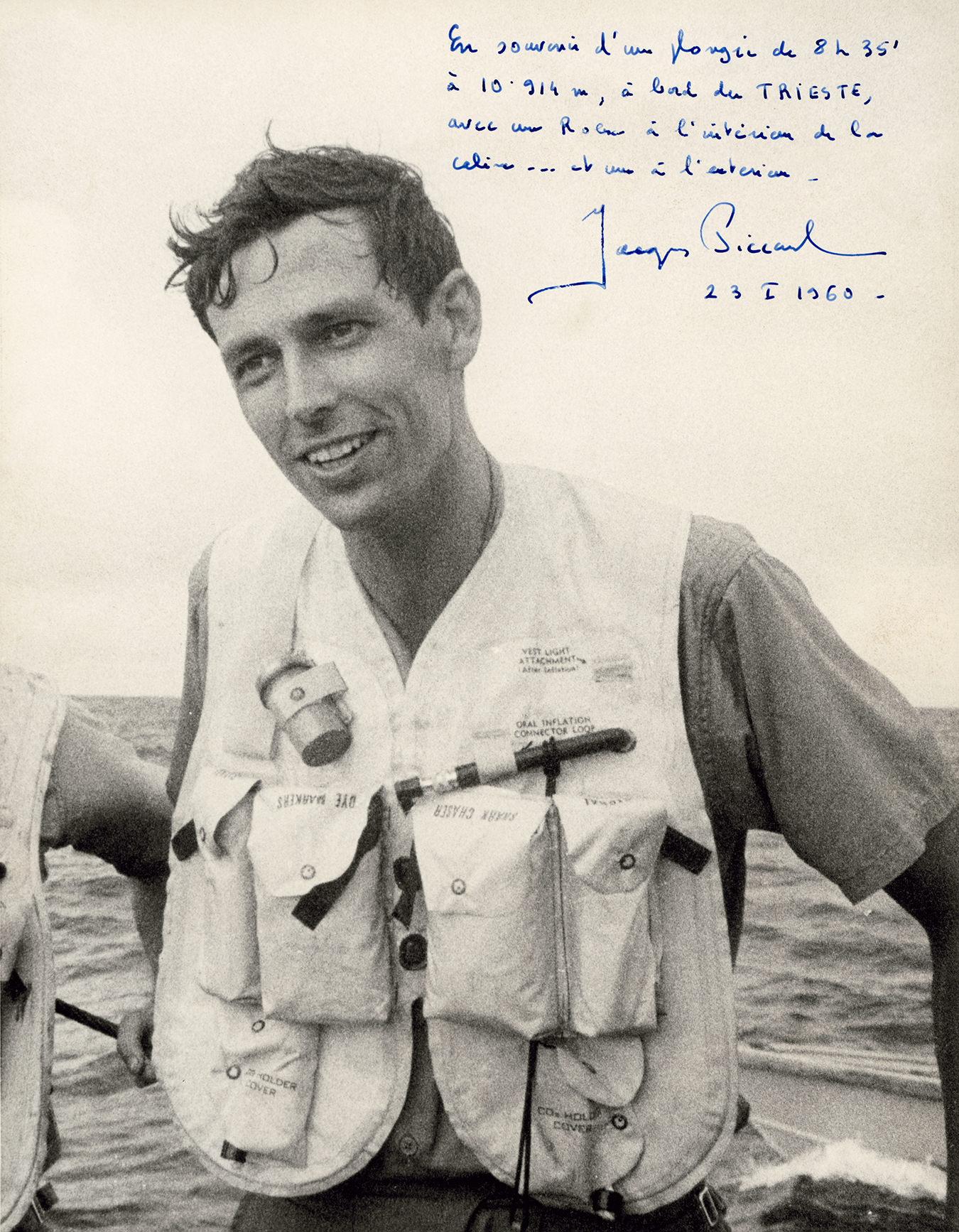

Jacques Piccard. Photo ©Rolex.

-

James Cameron’s submersible, the Deepsea Challenger. Photo ©Mark Thiessen/National Geographic.

The Outer Limits

Rolex and James Cameron.

Behind every great explorer, there is a great piece of engineering. From the intricacies of an orienteering compass or the mechanics of a wristwatch to the megacomplexity of a space shuttle, modern-day innovations have long replaced the stars’ guiding light to get us where we want to go.

James Cameron, for one, can attest to this. When the Canadian-born filmmaker and explorer set off at 5:15 a.m. on March 26, 2012, and descended 10,908 metres in the Pacific Ocean to a point called Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench, he became the first person to complete a solo dive to the deepest part of the ocean. Cameron’s transport was the bright-green Deepsea Challenger submersible, manufactured to propel downward like a reverse torpedo, conceptualized and fabricated by a small, brilliant team of engineers, scientists, and marine biologists including Australian engineer Ron Allum, who co-designed the sub with Cameron. The filmmaker’s solo seat for the six-hour-and-45-minute dive was a circular chamber, just over a metre in width.

“People love to be tested,” says Cameron, on dry land at a screening of his documentary Deepsea Challenge 3D, the film that documents the dive he undertook in partnership with Rolex and National Geographic. “[People] love to know what their limits are. Not everybody, but the ones that are drawn to this type of work, absolutely … When you’re out there and you’re far from shore, it’s a small, closed world.”

The 60-year-old Cameron can count himself among those driven few. His fascination with deep-sea exploration took hold during the filming of his 1989 sci-fi flick The Abyss, and it was the possibility of experiencing Titanic’s wreckage firsthand that propelled him to make that eponymous blockbuster film of 1998. Still, it took almost two decades before Cameron was able to carve out time in his busy schedule to go ahead with the Deepsea Challenge expedition.

If Cameron was Noah, then the Deepsea Challenger was his masterfully engineered ark—the submersible brought back 68 biological and geological specimens that had never been seen by scientists before. “Noah’s animals”, if you will, included shrimp-like creatures called amphipods, marine animals such as sea cucumbers, and “microbial mat” rock coverings containing organisms that are able to survive in the dark. The Deepsea Challenger was also a test run for Rolex, which affixed three experimental Deepsea Challenge wristwatches to the submersible’s hull and robotic arm, all of which tagged along for the open-ocean ride to endure the most colossal water pressure our planet has to offer. A distillation of Rolex know-how, the Deepsea Challenge timepiece is waterproof to the extreme depth of 10,908 metres. As Rolex puts it, the design “could be called over-engineering,” and the watch has earned itself a nickname: “the ultimate Oyster”.

If Cameron was Noah, then the Deepsea Challenger was his masterfully engineered ark—the submersible brought back 68 biological and geological specimens that had never been seen by scientists before.

In many ways Cameron’s dive was an ode to the Trieste expedition of January 23, 1960, when U.S. navy lieutenant Don Walsh and Swiss oceanographer Jacques Piccard became the first duo to ever reach the Mariana Trench. Manned by Walsh and Piccard, the Trieste—an Italian-built bathyscaphe designed by Piccard’s father, Auguste—carried along an experimental model of Rolex’s Deep Sea Special wristwatch, characterized by a spherical face that resembles a half-bubble. When the Trieste surfaced, Rolex received a cable at its Geneva headquarters: “Happy to announce your watch as precise at 11,000 metres down as on surface. Best regards Jacques Piccard.” (Years later, the producers of Star Trek: The Next Generation decided that going where no man had gone before was a feat worth canonizing, and reportedly named Patrick Stewart’s character Captain Jean-Luc Picard after Auguste Piccard and his twin brother, Jean-Felix, who was also a scientist.)

Fifty-two years later, Cameron would not only take inspiration from the Trieste expedition, but be mentored by Walsh, who is now 83 years old. “[Our dive] was a beautiful bookend to the history that Rolex made in 1960, which was such a powerful symbol at that time—it was like being a part of Edmund Hillary’s first summiting of Mount Everest, except it was the ocean version,” says Cameron. “For me, this is a relationship that’s based on my respect for the integrity of what Rolex does and what they represent, in terms of being a part of history.”

How deep or how far, how fast or for how long; how much stronger, better, harder can someone or something be pushed? For German-born Hans Wilsdorf, the founder of Rolex, pushing the limits was his timekeeping credo. Wilsdorf created a watch distribution company in 1905, and named his brand Rolex in 1908 (easily pronounceable in most languages and short enough to fit on the dial of a watch).

Wilsdorf spearheaded the creation of the Oyster, which debuted in 1926, and has gone down in the annals of timekeeping history as the world’s first waterproof wristwatch; in many minds, it is also the mother of all exploration watches. In 1927, British endurance swimmer Mercedes Gleitze swam the English Channel with an Oyster on her wrist—the watch’s first litmus test, and the first of many human-performed feats that would push Rolex timepieces to endure nature’s outer limits. Beneath the precise Swiss craftsmanship of each model, performance and functionality reign supreme.

In 1953, the Oyster’s successor, the Oyster Perpetual Submariner, was crafted to descend to 100, then 200, and finally 300 metres underwater. Two versions of the Oyster Perpetual Sea-Dweller followed (the 2000 in 1967, and the 4000, which launched 11 years later) and several more seafaring iterations, before the Oyster Perpetual Rolex Deepsea debuted in 2008, capable of withstanding depths of 3,900 metres.

This August, coinciding with the release of Cameron’s film Deepsea Challenger 3D, a new version of the Rolex Deepsea was introduced. The professional watch includes a “D-Blue” dial, which darkens from deep blue to black, symbolizing the descent into the ocean, with “Deepsea” in bright green letters, mirroring the shade of Cameron’s sub. Shrouded in an Oyster steel case is a 3135 calibre self-winding mechanical movement and a Triplock winding crown with triple waterproofness system, as well as the helium escape valve, a feature, patented by Rolex in 1967, that acts as a mini decompression chamber. The mechanics are a result of pioneering advancements such as Rolex’s patented Ringlock System, to which the device owes its waterproofness, pressure resistance, and strength.

“I used to tell my friends that a good dive watch should be a watch that you can pound a nail with,” says Cameron. “I never had the courage to demonstrate with my own Submariner, but I know it would have survived because it certainly had been through a lot, and has been with me on all my dives since the mid-eighties.” Joining the experimental Rolex timepieces on Cameron’s expedition was his personal Deepsea watch (worn on his wrist), as well as a replica of the Trieste’s 1960 Deep Sea Special timepiece for sentimental value. Cameron also took a few other good-luck tokens: three coins from an expedition yacht called Octopus, given to Cameron by its owner, Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen; a piece of steel drop-shot from the original Trieste, given by Walsh; and a couple of flags, one of which belonged to the Explorers Club. What the latter lacked in physical weight, they made up for in historical significance.

“[The team] gave me grief later for sitting on the flag, but I didn’t sit on the flag—it was folded up and tucked underneath the seat, right next to the emergency battery,” says Cameron. Today, it is framed and mounted on a nondescript wall in New York at the prestigious yet unstuffy headquarters for the 110-year-old Explorers Club, a non-profit organization that prides itself on promoting the scientific exploration of land, sea, air, and space. Naturally, Cameron is a member, as were Theodore Roosevelt and Sir Edmund Hillary; Rolex has been involved with the Explorers Club for the past few decades, and in recent years as a Corporate Partner in Exploration.

The union with the Explorers Club was a natural one for Rolex. An ongoing roster of famed explorers, such as Wade Davis, Sylvia Earle, and Leroy Chiao, have lectured at the club, and throughout the years its members have been responsible for an illustrious set of famous firsts: the first to the North Pole, the South Pole, the summit of Mount Everest, the deepest point in the ocean, and the surface of the moon. At the club’s headquarters on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, that adventurers’ instinct materializes in rooms bedecked with ancient memorabilia; almost everything has historical significance.

“I used to tell my friends that a good dive watch should be a watch that you can pound a nail with,” says Cameron. “I never had the courage to demonstrate with my own [Rolex] Submariner, but I know it would have survived.”

There is the boardroom table at which Roosevelt sat when planning part of the U.S. role in the Panama Canal; there is an antique chest that belonged to Captain James Cook; and (although most of today’s explorers are ardent conservationists) there is a trophy room displaying taxidermy through the ages, including a lion pelt collected by Roosevelt. The club now exceeds 3,000 members, including the aforementioned Walsh as honorary president, who took on the role after Sir Edmund Hillary’s passing in 2008. As part of Rolex’s continued partnerships of exploration, Hillary, along with Sherpa mountaineer Tenzing Norgay both wore and tested Oyster Perpetuals upon summiting Mount Everest in the Himalayas on May 29, 1953, climbing 8,848 metres above sea level. (The Rolex Explorer watch is often associated with Everest, but it was launched later that year in honour of the successful climb.)

Using real-life conditions and achievements—sometimes historic—to validate the quality of its watches is something Rolex has done consistently. Since Gleitze swam the Channel in 1927, each decade has seen its share of Rolex-supplied expeditions to test its devices in natural conditions. In 1957, for instance, French geologist and volcanologist Haroun Tazieff was equipped with Rolex models to study their resistance to corrosive volcanic gases; and in 1979 Sir Ranulph Fiennes and the members of his British Transglobe Expedition were equipped with Oysters. In the 1990s, the watch manufacturer was there for expeditions

with Norwegian adventurer Erling Kagge, who traversed the three “poles” (North, South, and Everest) over the course of five years, and in 2006 for Rune Gjeldnes when he crossed the length of Greenland, the Arctic, and the Antarctic on skis. In 2010, eight individuals trekked and dived through Canada’s North in a 45-day expedition of the polar region’s submerged and overland territories. With Rolex as title sponsor and five Deepsea watches in tow, they gathered scientific data on the effects of global warming and the area’s delicate ecosystem.

Many of these adventurers carried not only watches but also Explorers Club (and often National Geographic Society) flags in tow. The flag that travelled in Deepsea Challenger, #161, is one of just 222 official Explorers Club flags that traverse the globe—it is also the only object on the planet that has travelled to the lowest point in the world as well as the highest (Mount Everest) before reaching its resting place in Manhattan alongside the moon-landing flags. Indeed, most of the moonwalkers were Explorers Club members, including Buzz Aldrin, who spoke there this past October.

Cameron gives a nod to that moon landing when asked about the actual experience of his record-breaking dive. “I knew that the astronauts had so many things to do up there that they didn’t think about it until they got back,” he recalls. “Then, when people would ask them how they felt, the astronauts couldn’t answer the question because they didn’t allow themselves to have a philosophical or a reflective moment.”

With that in mind, Cameron chose to incorporate those moments in the only way he knew how: by making them a part of his underwater task list. The essence of being in the pilot’s seat had to be accounted for in a measured moment. “I actually wrote in my timeline, stop and think. I literally wrote it down.” And so, on Deepsea Challenger, Cameron took a few precious minutes for himself. “I just sat there, and looked out the window, and thought about where I was. And if it wasn’t in my timeline, I wouldn’t have done it.”