Shobac Cottages

Brian MacKay-Lyons and archi-tourism in Nova Scotia.

The Shobac Cottages blend aspects of modern design with Nova Scotian architectural heritage. Photo ©James Steeves.

Perched atop a remote cliff in Nova Scotia, overlooking the Atlantic Ocean, they stand like a row of silent sentinels at the edge of the world. Behold the Shobac Cottages. These four structures are part of a compound that has become an intellectual and social gathering place for people from across Canada and the globe. What started as an educational project has now taken on a life of its own.

Since 1994, architects, engineers, builders, professors, and students have gathered at the 60-acre Shobac farm to learn, to teach, and to build. Directed by internationally acclaimed architect, teacher, and visionary of the vernacular Brian MacKay-Lyons, the Ghost Architectural Laboratory—or simply Ghost Lab—is a two-week exercise in how to design as well as construct that is held every summer.

When MacKay-Lyons began the cottage project 16 years ago, he expected they would serve as living quarters for visitors who show up every summer to participate in conferences, events, and educational sessions of various sorts. They were started during a Ghost Lab and finished later by MacKay-Lyons. Since then, however, interest and demand have grown to the point where the cottages are rented out from May to November. Besides, there’s a mortgage that has to be paid off.

Each of the Shobac Cottages has a private terrace facing the Nova Scotian coastline. Photo by Brian MacKay-Lyons.

Although the MacKay-Lyonses’ homestead is remote, it’s not isolated, and the distinction is immediately clear to anyone who makes the journey. Insisting that architecture is nothing more than a means to an end, MacKay-Lyons has used his considerable skills to establish a multi-faceted community where visitors can work and/or play, depending on why they’ve come.

“There’s a concentration of our work here,” MacKay-Lyons explains. “The place has a village feel to it. That works because the people who stay here are typically interested in archi-tourism and ecotourism.”

But the simplicity of MacKay-Lyons’s work is deceptive; his buildings form part of an ongoing exploration of the relationship between architecture, memory, culture, and the physical environment. His passions have little to do with the world of starchitects and their pin-up projects. In fact, his work amounts to a not-so-subtle critique of conventional architecture, which has, in his opinion, become a sort of throwaway activity designed either for entertainment or expediency.

“There’s a popular misconception that good design is about making things pretty or flashy,” he says, “but good design tends to be silent.”

And, he insists, “Good design doesn’t have to be expensive.”

If anything, MacKay-Lyons has gone to the opposite extreme; he emphasizes architecture as something that should be available to all, not just the rich. Since he graduated from the Technical University of Nova Scotia (now Dalhousie University) with a bachelor’s degree in architecture and environmental design, he has devoted his talents mostly, although not exclusively, to housing, usually the sort found in urban neighbourhoods and rural areas throughout Nova Scotia.

The Shobac Cottages are built upon a 60-acre property in Upper Kingsburg, Nova Scotia. Photo ©Manuel Schnell Photography.

MacKay-Lyons first gained international attention for a series of infill residential projects and rural houses in Halifax in the 1980s. Working in a pared-down style that could be called vernacular modernism, he argues that even the most modest, unassuming buildings can be beautiful. Furthermore, he asserts that true beauty is found in utility, material honesty, and architectural integrity. His aversion to high design and any form of pretentiousness gives his work a lean, almost muscular quality.

As the Shobac Cottages make clear, the MacKay-Lyons ideal is based on the notion that true luxury lies in having just enough, and not being weighed down and overwhelmed by excess.

As the Shobac Cottages make clear, the MacKay-Lyons ideal is based on the notion that true luxury lies in having just enough, and not being weighed down and overwhelmed by excess. Lined up one beside the other, the four cabins have their roots in the anonymously built houses that can still be found throughout the Nova Scotian countryside. The construction—mainly cedar shiplap—is basic and straightforward.

On second glance, however, the buildings reveal a marvellous simplicity almost Shaker-like in spirit. The identical cottages are situated about three metres from one another. They each have a small terrace facing southwest to the ocean and a roof that slopes gently toward the water. The entrances look northeast to a rural landscape that MacKay-Lyons rightly calls “amazing.”

Inside, the cottages are finished in wood; that includes floors, walls, and ceilings. Except for their exquisite sense of space and connection to the landscape, these compact cabins might be considered primitive, even verging on unfinished. But the design of these buildings is all about creating spaces, not architectural objects.

“People are tired of all that Daniel Libeskind flash,” says MacKay-Lyons, referring to the Polish-American architect whose credits include the Jewish Museum in Berlin and the Michael Lee-Chin Crystal at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto. “The task is to be a responsible architect.” That means sustainable buildings designed in harmony with what’s at hand, physically, and culturally. “The best way to be green,” he says, “is to be local. In Nova Scotia, the ethic of fragility has always been such a part of our history. But that fits with the kind of environmental ethic that has become fashionable these days.”

A wood-finished cottage interior. Photo by Brian MacKay-Lyons.

He continues, “The kind of work we do has an audience. There’s a lot of work for us—more and more people are interested in regionalist architecture that takes climate and local material culture into account. We are a small boutique architectural firm. Our practice gets a lot of its business from this desire for environmental stewardship.”

No doubt about that; MacKay-Lyons’s buildings have been recognized with more than 75 major awards, including four Governor-General’s Medals and an Honor Award from the American Institute of Architects. His present firm, MacKay-Lyons Sweetapple Architects, was formed in 2005 when he joined forces with long-time collaborator Talbot Sweetapple. Before that, MacKay-Lyons spent a number of years living abroad, studying and working in China, Japan, Italy, and California. Born and raised in the Nova Scotian village of Arcadia, the architect returned to his home province in 1983 and opened his first office in Halifax in 1985.

The move to the hinterland came over the course of years. It started about three decades ago when MacKay-Lyons and his wife, Marilyn, bought an old house built in 1753. It came without much land, but over time, the couple acquired one small lot on their property after another.

“We would buy an acre here, an acre there,” he says. “I cleared the land with my chainsaw. And we put every dollar we made into it. It represents a tremendous act of will. It was rediscovered by me. The site has deeply historical and archeological nature. It is littered with the ruins of communities that used to be here.”

Keep in mind that Europeans first arrived here in the 16th century. When Samuel de Champlain explored the East Coast in the early 1600s, he found small dwellings already built by the European fishermen who frequented these shores. Even today, Upper Kingsburg, where Shobac is located, remains remote. The largest nearby town, Lunenburg, now a designated UNESCO World Heritage site, is 20 kilometres up the road.

“The south shore of Nova Scotia is really beautiful,” says MacKay-Lyons. “But Lunenburg County is particularly beautiful. It’s a mix of rugged seascape and pastoral landscape.”

Over time, other Ghost Lab buildings and projects have been added to the property, including the striking studio building, a remarkable barn-like structure that stretches 27 metres. It, too, is characterized by an all-pervading sense of clarity and informed by a simplicity that is really anything but.

“Architecture’s not about consuming the landscape, but about finding ways to frame it and enhance it,” says MacKay-Lyons. “The task is to produce something authentic.”

Then there’s the historic Troop barn, an unusual 19th-century building that MacKay-Lyons rescued from demolition. The octagonal structure was dismantled and rebuilt on his property, where it now serves as a venue for large events—everything from concerts and dramatic performances to lectures and weddings.

“I’m hopelessly democratic,” MacKay-Lyons admits. “I believe all things should be accessible. The motivation is highly idealistic. I also subscribe to the Field of Dreams school of business: build it and they will come. It’s a kind of utopian dream. The first thing people see when they come to stay at the cottages is a highly abstract, modern version of a house in a fishing village. But by the second night, they’re all having dinner together. People who stay here rediscover community.”

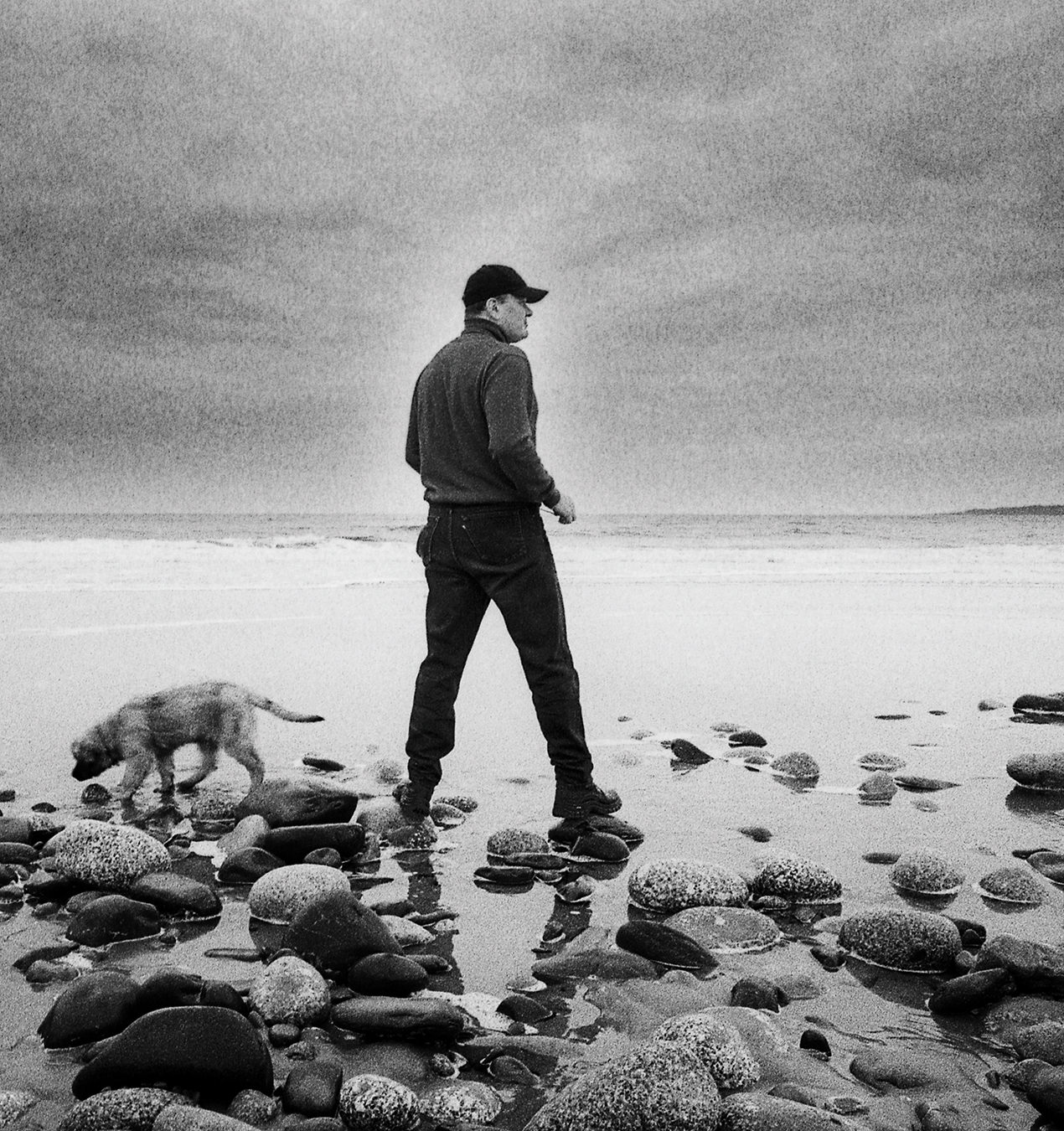

Architect Brian MacKay-Lyons. Photo ©Manuel Schnell Photography.

MacKay-Lyons and his firm have also made a point of moving beyond his compound to work with his neighbours in Upper Kingsburg and beyond. Look carefully, and you might see a number of buildings in the village for both locals and those that vacation in the area.

“Architecture’s not about consuming the landscape,” he says, “but about finding ways to frame it and enhance it. Think of the idea of slow growth. The task is to produce something authentic. You can sniff out phoniness immediately. It’s easy to forget, but beauty comes out of pragmatism.”

Despite the idyllic local scenery, MacKay-Lyons worries deeply about the direction Canada and the rest of the world are headed in the 21st century. “What gives us the right to build all that crap, and to make a quick buck at the cost of future generations?”

MacKay-Lyons prefers the image of the architect as farmer, a man not just tending his own fields, but carving those fields out of the wilderness.

“Architecture began with agriculture,” he explains. “There’s nothing more architectural than making a field. The scale is big, but it’s architectonic stuff.” MacKay-Lyons’s tools are just as likely to include a chainsaw as a computer. “I’m the architect—the guy in the rubber boots shovelling sheep shit,” he jokes.

But MacKay-Lyons is no curmudgeon; he also has an important career as a professor of architecture at Dalhousie University in Halifax, where the 57-year-old architect is revered by his students. There, he preaches a gospel of, “If you want to change the world, you’ve got to be a teacher. That’s the only way to have some small effect on what happens.”

MacKay-Lyons often talks about how students become colleagues, and his property has become a meeting ground for many of his former charges. His sense of mission and ability to put architecture within the larger context are rare gifts.

As he also likes to point out, like much of Canada, the Maritimes have been content to settle for architectural mediocrity. That’s no longer enough, he insists. “We all spend our time travelling to places that are beautiful. Why should we settle for less where we live?”

_________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter here.