-

Incles Vallety with Alt de Juclar peak in background. Photo ©Elena Aliaga/iStockphoto.

-

Margineda Bridge, a 12th-century Romanesque structure. Photo provided by Andorra Tourism.

-

Andorra, nestled in the Pyrenees. Photo ©Fonin/Dreamstime.com.

-

The town of Ordino, Andorra. Photo ©SOMATUSCANI/iStockphoto.

-

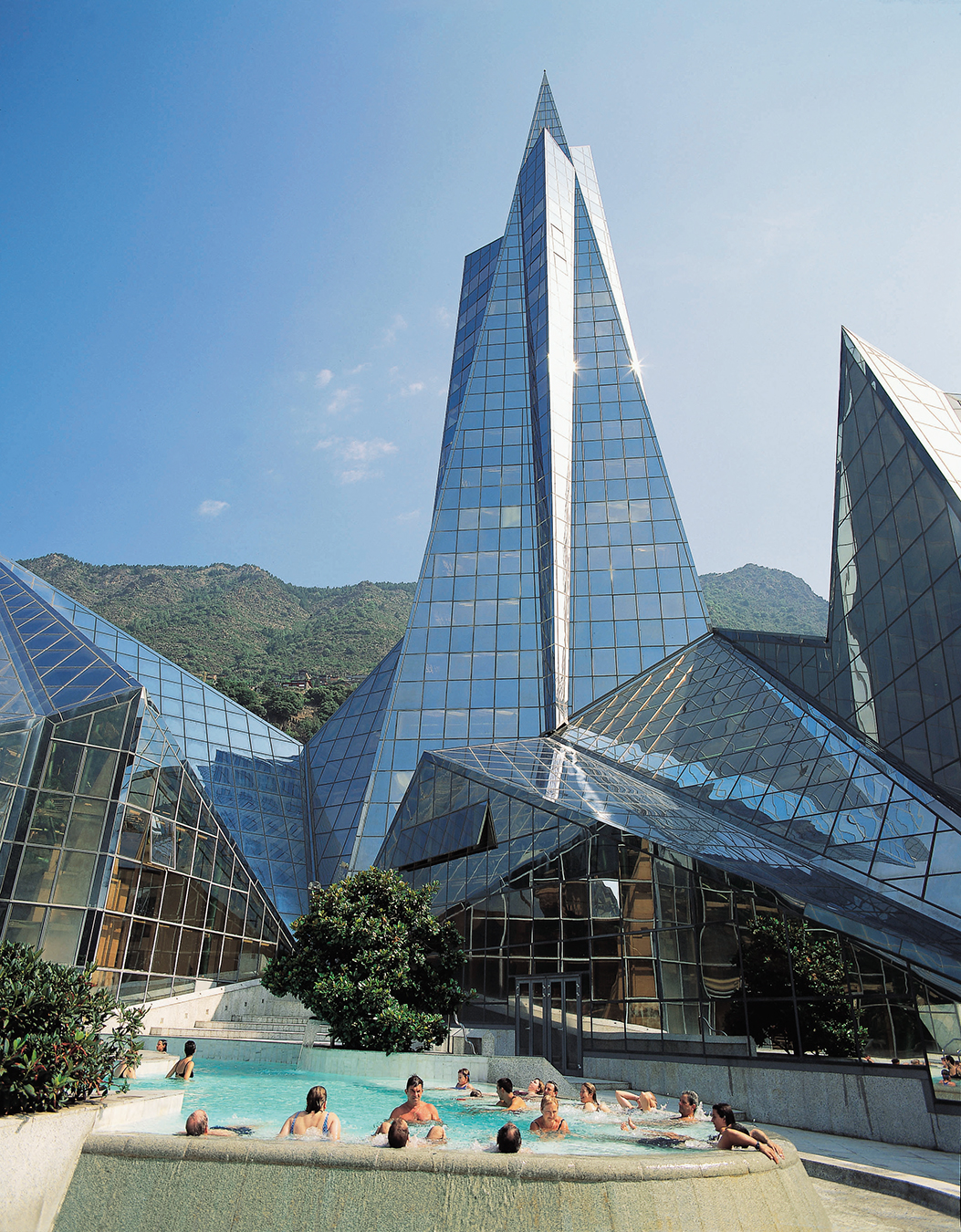

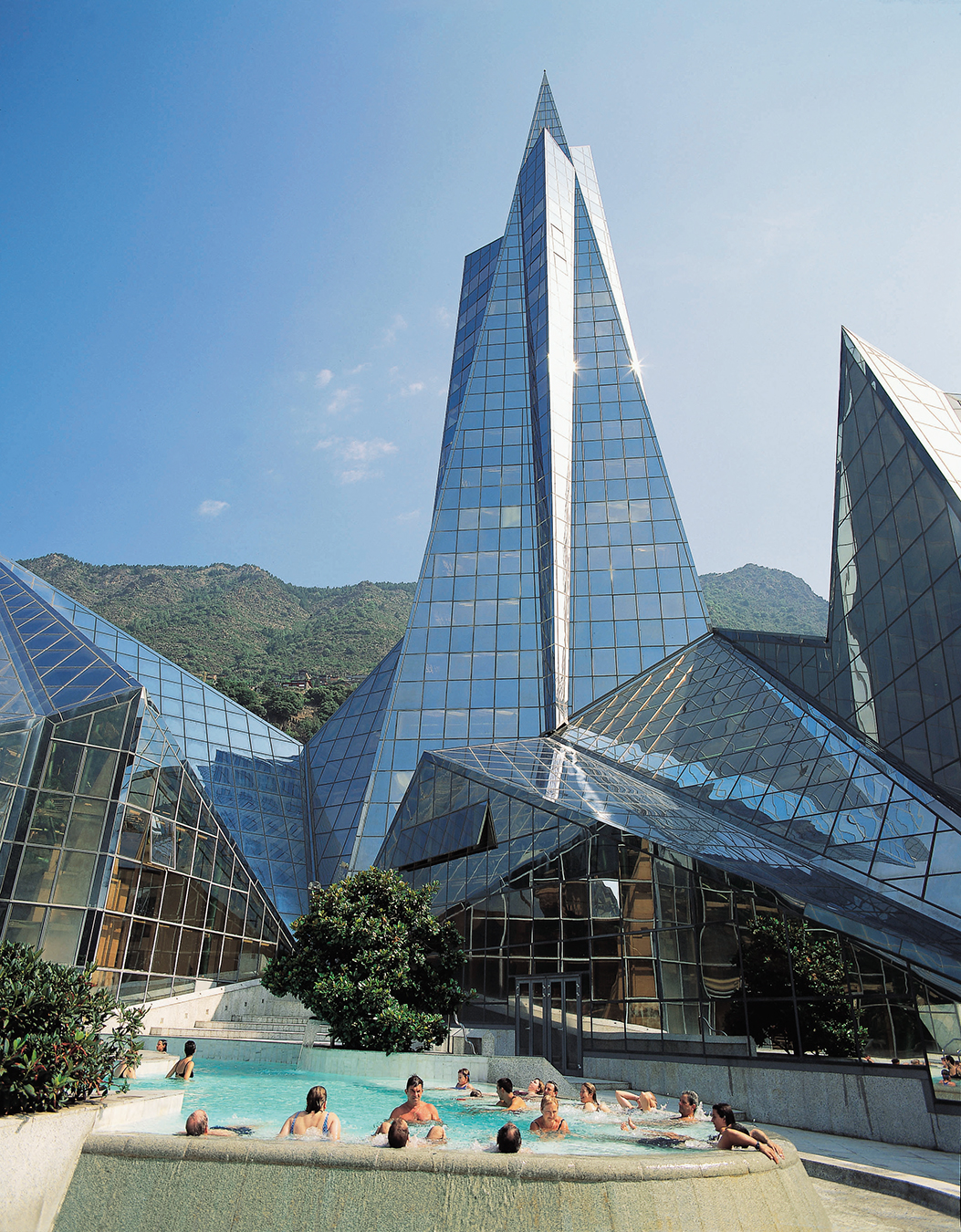

Caldea, Europe’s largest spa, in Andorra la Vella. Photo provided by Andorra Tourism.

Andorra: One of the Smallest, Most Beautiful Countries in the World

Hidden in the Pyrenees.

Incles Vallety with Alt de Juclar peak in background. Photo ©Elena Aliaga/iStockphoto.

Where I live in the deep south of France, the mention of Andorra is synonymous with a purpose-driven day trip. Around here, landlocked Andorra equals cross-border shopping—cross-border because, well, here’s where the contradictions begin. Andorra is not a European Union member state, but it does use the euro as its official currency. And of the 12 million people who visited in 2008—half of whom were Spanish, the rest mostly English, American, and French—it’s safe to say that, at some point, all received a spoken gràcies. Not gracias, because Andorra’s official language is Catalan, the 1,000-year-old tongue heard across the broad swathe of land that encompasses the Spanish community of Catalonia and—witness the bilingual signage—extends far into southern France.

For a small country of 468 square kilometres (barely larger than Barbados), Andorra has a remarkably stable history. Its inaccessibility—it is tightly wedged high in the Pyrenees between France and Spain—largely explains why it has managed to keep its independence. Even today, no trains go there—only buses—and the closest major airports are in Barcelona and Toulouse, both approximately 200 kilometres away.

I begin my road trip to Andorra in Spain, in the town of La Seu d’Urgell. At its edge stands El Castell de Ciutat, a hotel owned by the Tàpies family, who also look after the 16th-century fortress that crowns the hill above their property. Born in Andorra, Swiss-trained hotelier Jaume Tàpies is, like his birth country, complex. He lives in Spain, works in Paris, speaks seven languages, writes novels during the four flights a week he averages as international president of Relais & Châteaux, and is contagiously passionate about the region he grew up in, and what goes on there.

“Let me talk to you about contrabandistas,” he says as we drive up a narrow road just beyond La Seu d’Urgell. “After the wars, Andorra became the place for things you couldn’t find in Spain.” The Spanish village of Estamariu, where we are headed, is one of the most important smuggling passes in the mountains, he tells me. (“You should see this in winter,” Tàpies responds when I remark on the perilous drop at one side.) With rivers like tinsel ribbons below us, and stunning scenery all around, we are in the realm of the birds that draw ornithologists to the Pyrenees, eagles and vultures of mythic size with wingspans of almost three metres.

Andorra, nestled in the Pyrenees. Photo ©Fonin/Dreamstime.com.

If you follow the right track across these gothic mountains, you come to Andorra. Now, in the sunlight, the only fauna are cream-coloured cows, tinnily clanging their way across a meadow. “At night, you drive this road, you can find anything,” Tàpies says cheerfully. “Wild boar. Deer. Two brown bears were seen here recently.” Smuggling still goes on; cars with headlights off wind their way down the precipitous route.

Soon we are in Estamariu, a stone’s throw from the Andorran border. The way into this 12th-century village is so narrow that Tàpies must fold in one side mirror to manoeuvre between two stone buildings. He indicates a house. Blue pigment around doors and windows is common in Andorra and the surrounding region. “It protects against witches,” he says.

Besides the fun of retracing the smugglers’ trail, Tàpies has brought me here to sample the rustic cuisine at Cal Teixidó, a small hotel and restaurant that’s known for its regional cooking. After an elegant introduction (within minutes, a local tomato and pink-skinned apple appears as an amuse-bouche, the tomato micro-diced, the apple thinly sliced, anchovy, chives, and vinaigrette bridging the flavours), we sample the woodsy robellons mushrooms beloved by Andorrans, and a risotto deepened with sausages, ceps, and rosemary, while the rumble of conversation from local farmers percolates up from the bar below.

As one of the oldest European nations, Andorra has an eccentric history that dates back to around the first millennium when, legend has it, Charlemagne himself first established Andorra as its own territory.

Theoretically, we could now take a back road across the mountains to Andorra, avoiding the sharp-eyed Spanish border guards, but we don’t. The next day we enter Andorra legally. “Much of this is new,” says Tàpies as we leave the busy highway and head into the back streets of his mother’s home town of St. Julia. “It was quiet here when I was a boy,” he says. The main industry then was tobacco growing, and self-sufficient farmers raised pigs, rabbits, and vegetables. “Now people work in banks.” The lack of income tax, inheritance tax, and gift tax goes far to explain why Andorra numbers 60,000 foreigners among its 82,000 population.

Andorra is a dichotomy. On one side of the highway are billboards for Winston, Camel, and Marlboro, and vast shopping centres, on the other a Romanesque stone bridge; Andorra is rich in architecture from this period. In 1982, these medieval structures withstood floods that damaged and washed away modern bridges.

The town of Ordino, Andorra. Photo ©SOMATUSCANI/iStockphoto.

As one of the oldest European nations, Andorra has an eccentric history that dates back to around the first millennium when, legend has it, Charlemagne himself first established Andorra as its own territory. In 1278, Andorra officially became a principality with the signing of a paréage—a unique power-sharing agreement—which gave joint sovereignty to two co-princes, the Count of Foix and the Bishop of Urgell. (To this day, both the Bishop of Urgell and the President of France receive Andorran passports when they are named or elected.) In yet another historical anecdote—this one worthy of Gilbert and Sullivan—Tàpies tells how, in 1934, a Russian claiming royal acquaintances convinced all but one of the Andorran members of parliament to name him King Boris the First. Objections were raised, but enough to-ing and fro-ing took place that Boris, who was eventually arrested, was able to rule for eight days. Then, as now, his “kingdom” included the bishop’s palace in La Seu d’Urgell, a piece of Andorra in a Spanish town.

“We’re very proud to be Andorrans,” Tàpies continues, describing how the country’s national song tells the story of Andorra herself. Was she Charlemagne’s daughter, as legend maintains? “Yes and no,” says Tàpies. “It’s like the Pyrenees,” he adds, alluding to the range’s apocryphal origins as the rocky tomb where Hercules buried his lover, Pyrene.

No question, this small country is growing. Everywhere, construction cranes stand like leggy insects while engineering feats span chasms and push tunnels through mountains. Passing the country’s capital, Andorra la Vella, I notice a glass-spired cathedral at its centre; this is Caldea, Europe’s largest spa, which has an indoor lagoon that holds 500 people, and is ideal for soothing post-skiing muscles. Tàpies, a three-time Spanish cross-country skiing champion says he can drive from his hotel to a ski lift in 20 minutes. “If I leave early,” he adds, naming remote Arcalis as a favourite destination for its abundance of fresh, virgin snow. The high altitude extends a season that in 2008–2009 ran from November to May. Once the snow melts and the wildflowers bloom, hikers move in to explore the placid Incles Valley, or the natural park around Coma Pedrosa, at 2,942 metres, Andorra’s highest peak.

Caldea, Europe’s largest spa, in Andorra la Vella. Photo provided by Andorra Tourism.

On our final day in Andorra, stuck in traffic on its single main highway, it’s hard to conjure up a sense of isolation. Andorra allegedly has 2,000 shops selling a variety of goods including Swiss watches, French perfume, Italian fashion, U.S. sportswear, and just about everything else. Before we head south to Spain through the spellbinding Cadí-Moixeró Natural Park, we stop, intending to buy oil made from local arbequina olives, and that is all, but we leave the hypermarket with the oil, a non-stick paella pan, wine, T-shirts, sunglasses, and more.

The lure of the duty-free bargain may remain, but my conventional perception of Andorra has changed, my impression now refracted through Jaume Tàpies’s prism. We continue on a route he has suggested that takes us away from the commercial chaos of Andorra la Vella toward the small town of La Massana, with its buildings of local stone that, from a distance, are sombre brown, but reveal themselves close up as a patchwork of dark grey, ochre, and russet. The road winds its way through bastions of rock, a small river chuckling alongside it. We arrive at our destination, Pal, a community of neat houses clinging to a hillside. I remember a comment Tàpies made as he pointed out routes on a map of Andorra: “There are little churches lost in there.”

Leaving the car, I follow a steep path to the small Romanesque church of St. Clement, making my way under a low arch onto a broad ledge of rock. I’m at the level of the slate rooftops. There’s a smell of newly cut grass, scarlet geraniums blaze in hollowed logs, the sky is flawless, the vista magnificent, and the church bell striking the half hour is the bass to the squeak of inadequately oiled brakes as a cyclist descends the hillside opposite. Basking in the late afternoon sun and thinking over the past few days, I recall Tàpies pointing out a village just 10 minutes from Spain. Or five hours if we choose, contrabandista-style, to return via the mountain backroads.