The Rediscovery of the 1845 Franklin Expedition’s Lost Ships Is a True Canadian Story

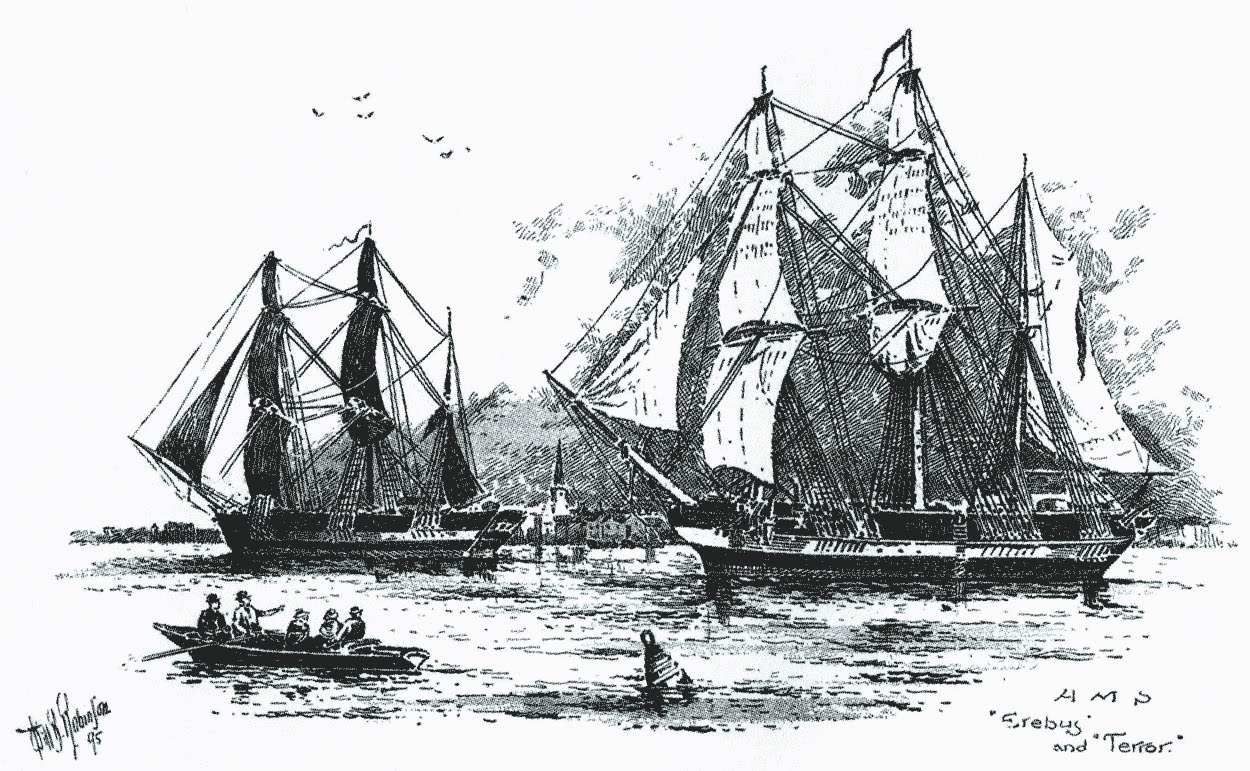

HMS Erebus and HMS Terror constitute a one-of-a-kind National Historic Site.

It’s a rare mystery that takes close to 170 years to get solved. Still, the 21st-century rediscovery of the two ships from the ill-fated 1845 Franklin expedition continues to make headlines.

Maritime history enthusiasts worldwide were electrified in 2014 when Parks Canada researchers located the submerged wreck of HMS Erebus–Sir John Franklin’s 372-ton, 105-foot-long ship–in Nunavut.

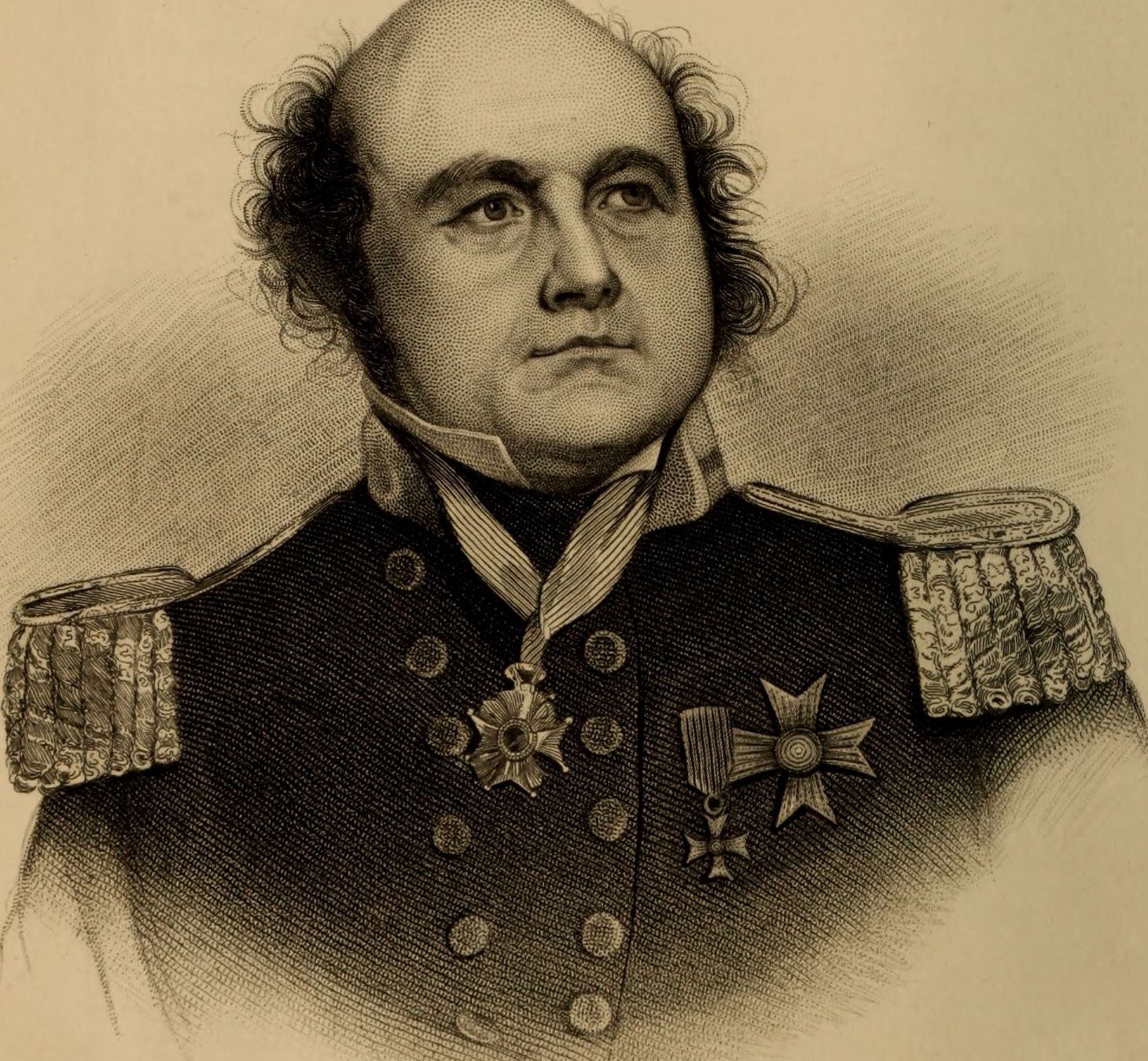

The Royal Navy officerʻs perilous bid to secure his legacy by finding the fabled Northwest Passage to India ended in catastrophe with the deaths of 129 officers and seamen. Scurvy, starvation, and freezing were among the causes, as the ships got trapped in pack ice.

Franklin—known as the “Man Who Ate His Boots” after subsisting on shoe leather during an 1819 overland expedition from Hudson Bay—fell victim to overconfidence. His 1845 expedition relied too much on canned food and brought inadequate winter clothing.

Sir John Franklin

In 2016, HMS Terror, the support ship under the oversight of Captain Francis Crozier, was also located. Both these British Royal Navy bomb vessels were remarkably well preserved in Canadian Arctic waters off King William Island, home to the Inuit hamlet of Gjoa Haven.

Long before the 10-year anniversaries of the rediscoveries in 2024 and 2026, the Franklin expedition has preoccupied the Canadian imagination.

Folk singer Stan Rogers’s 1981 classic “Northwest Passage” was once selected by CBC Radio listeners as their preferred alternative Canadian national anthem. Pierre Berton’s 1989 book The Arctic Grail: The Quest for the North West Passage and the North Pole, 1818-1909 was a number one bestseller in Canada.

More recently, The Terror, a hit 2018 AMC series based on a Dan Simmons horror novel and with supernatural elements drawing on Inuit mythology, brought awareness of the expedition to a wider audience.

Artwork depicting the Franklin expedition

Major credit for the ships’ real-life rediscovery goes to Inuit oral history (Qauijimajatuqangit). These wrecks were located where local First Nations had always said they would be. The area is now a National Historic Site, administered jointly by Parks Canada and the Inuit. A cornucopia of artifacts still awaits retrieval from the ships, potentially including priceless early polar exploration photos and logbooks.

“Parks Canada works closely with the people of Nunavut to get permission to go down and retrieve artifacts,” says Ross Day, a Quark Expeditions historian who nurtured his Franklin passion at Cambridge’s Scott Polar Research Institute. “It is an integral part of modern-day Inuit cultural history. The Inuit knew where the ships were and what happened to the men via their long-standing traditions. It’s only really in the last decade or so that researchers have finally started taking it seriously and listening.”

During the feverish hunt for the lost expedition that kicked off in the late 1840s, passions and prejudices came to the forefront.

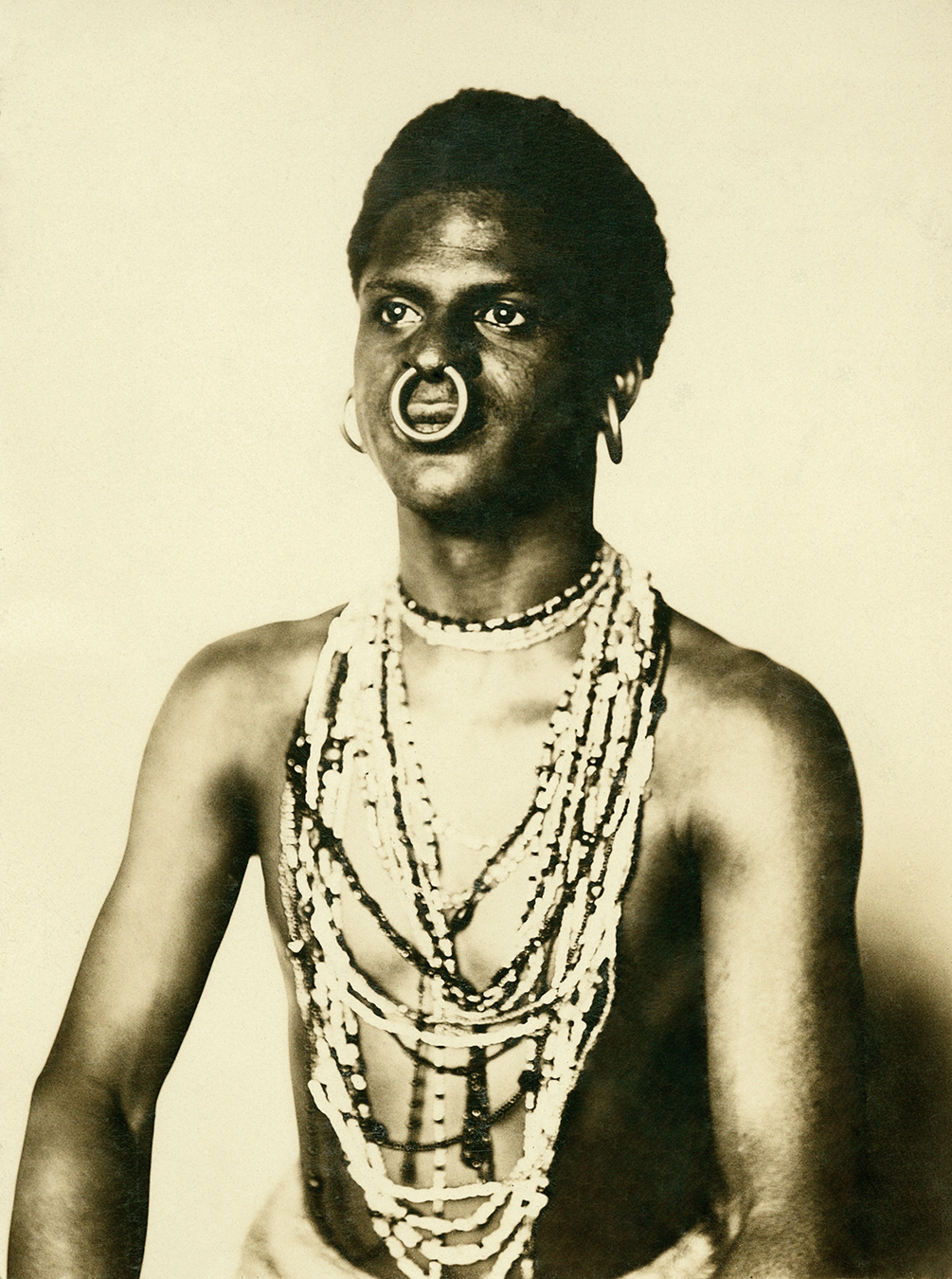

Photos by Lucas Aykroyd

In 1854, when Scottish explorer John Rae reported hearing from Inuit hunters that some Franklin survivors had engaged in cannibalism, he drew intense blowback from the legendary novelist Charles Dickens and Lady Jane Franklin, the commander’s widow. They argued that no British sailor would—even out of desperation—eat human flesh, although recent archaeological studies have supported the allegations.

Nowadays, visitors to Canada’s North can retrace the Northwest Passage quest without suffering the privations of 19th-century explorers. A guest on the Quark Expeditions luxury ship Ultramarine might, for instance, dine on lobster bisque, steak au poivre, and chocolate cake instead of salt beef, porridge, and tinned vegetables like Franklin’s crew.

Yet although exploring the bleak, unforgiving Arctic has become easier with modern technology, echoes of the Franklin expedition still resonate amid today’s most pressing crises.

Photos by Lucas Aykroyd

Climate change not only endangers Arctic wildlife from belugas and narwhal to polar bears and wolves. It also means that the Northwest Passage sees reduced sea ice cover for more days annually than before. That, in turn, ramps up geopolitical tensions as the world’s naval and shipping powers challenge Canadian Arctic sovereignty.

Learning from the Victorian-style hubris that ultimately doomed the Franklin expedition thus seems particularly timely. Especially for Canadians who pride themselves on resilience, from international hockey battles to the great wars of the not-so-distant past to the frozen North.