-

The platinum-plated Perfect Pencil from the Faber-Castell collection.

-

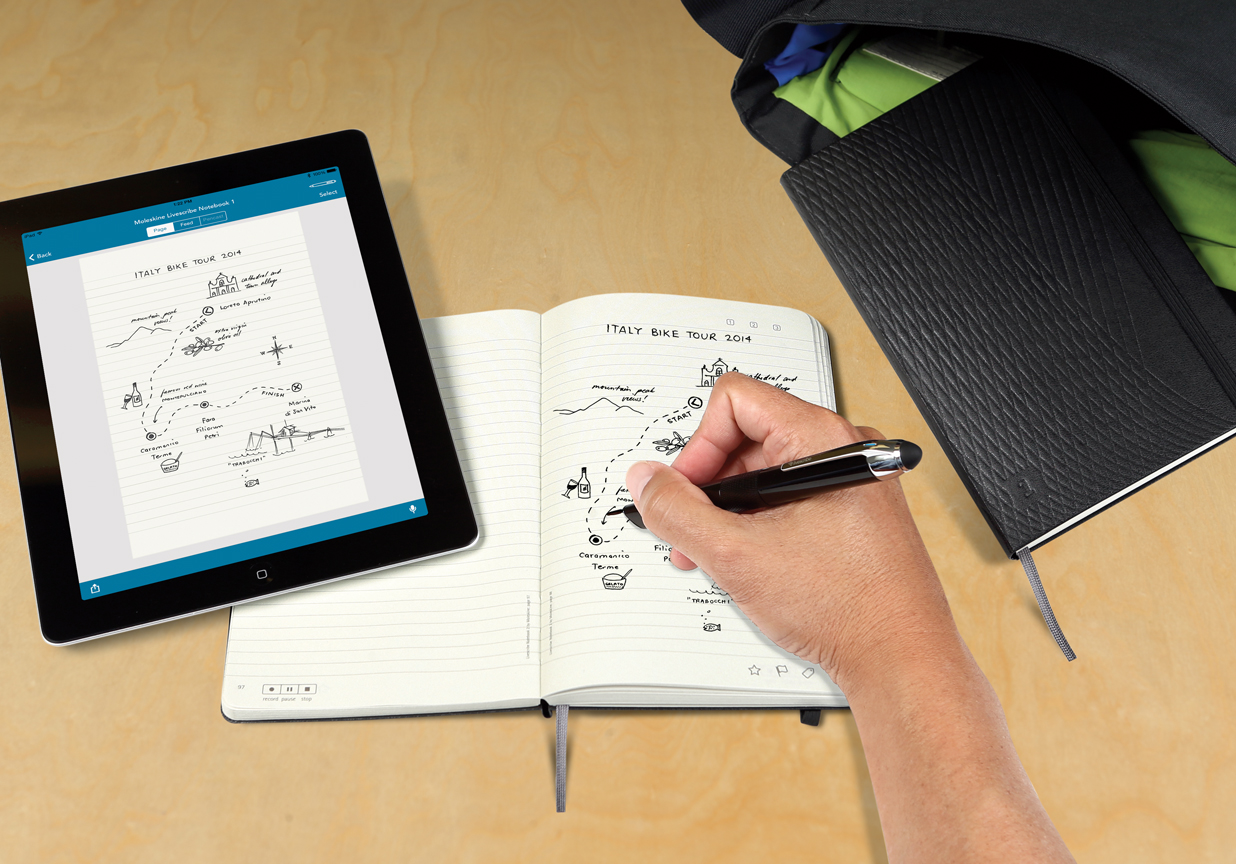

Faber-Castell is the largest producer of wood-cased pencils in the world.

-

-

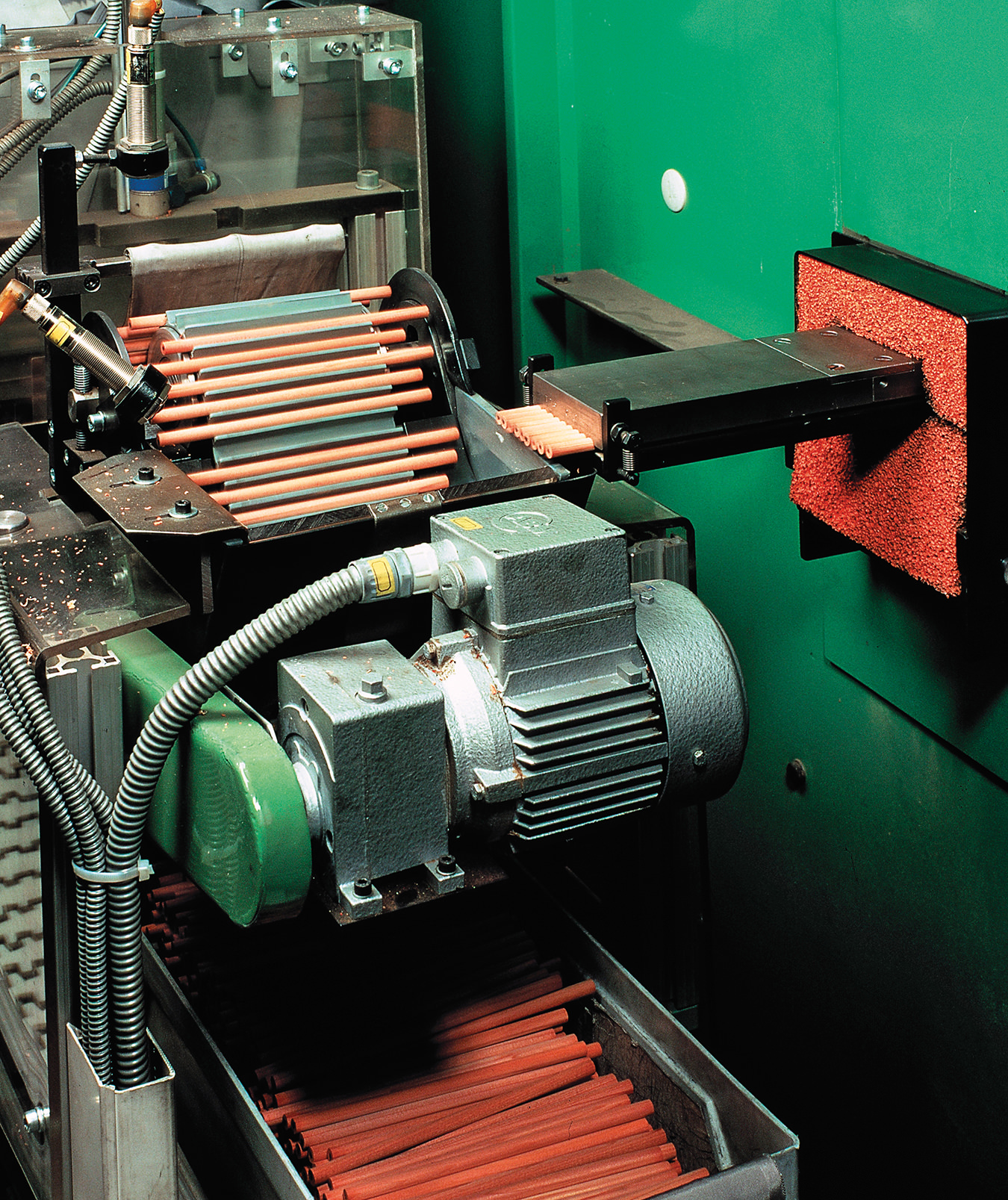

Stamping pencils.

-

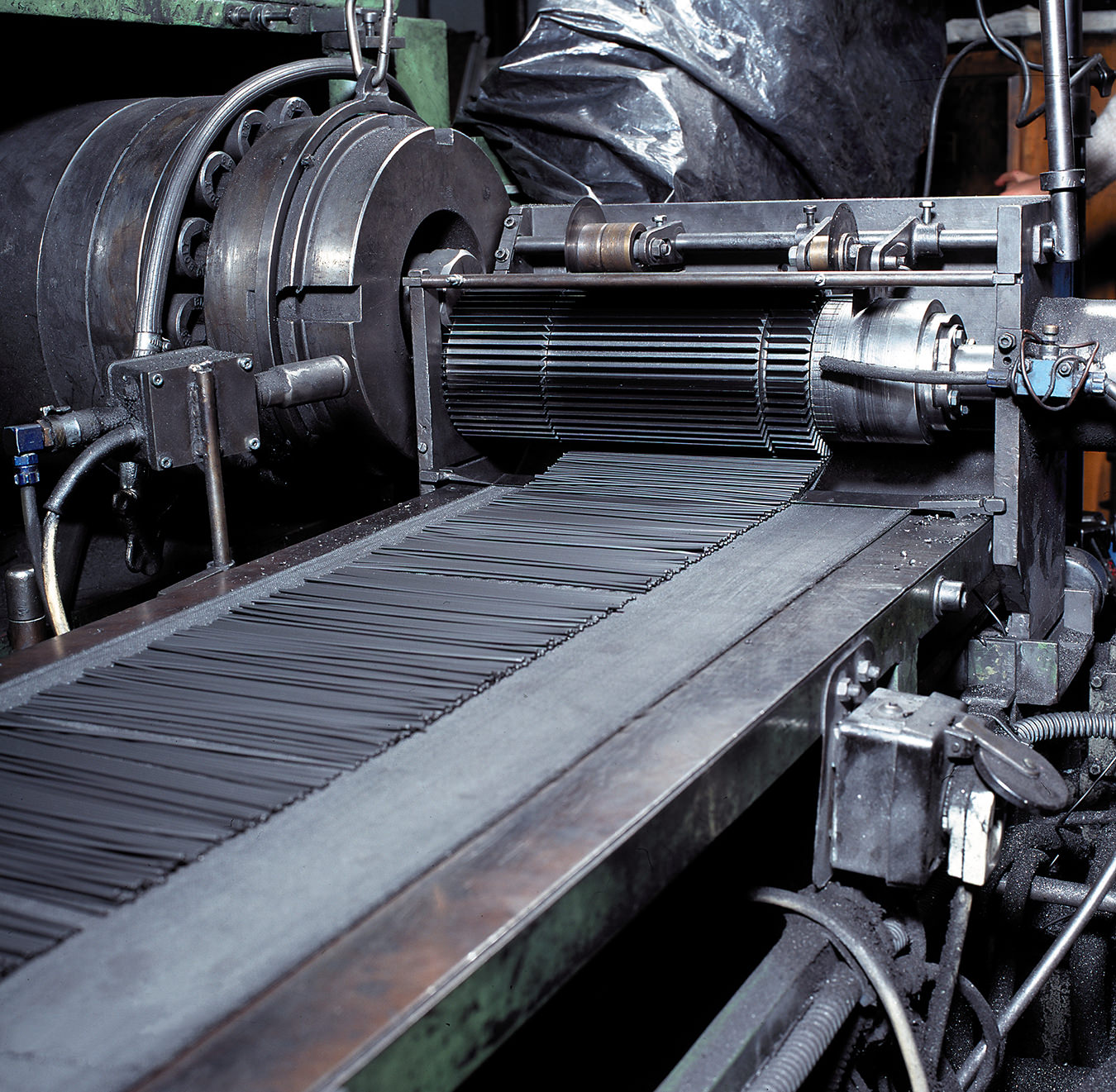

The graphite manufacturing process.

-

The graphite used in Faber-Castell pencils comes in 16 different degrees of hardness.

-

The 2012 Pen of the Year combines oak, the symbol of eternity, and gold, the symbol of wealth and good fortune.

-

The 2011 Pen of the Year is made from jade and marks the 250th anniversary of Faber-Castell.

-

The Guilloche pen.

-

The 2009 Pen of the Year. Its barrel is made of horsehair, hand-woven by Dorit Berger, the only expert still mastering this traditional art in Germany.

Faber-Castell

Still sharp.

There is nothing stale about the historic headquarters of Faber-Castell, steps away from Nuremberg in the small town of Stein, Germany. Far from the sense that historic can imply, the stationery company’s birthplace is very much alive with its ongoing advancement of the pencil. The property is home to a bustling factory; office headquarters that act as the figurative meeting point for the company’s 23 global head offices; and, perhaps most magnificently, the Faber-Castell Castle. More than a century old, it is an architectural marvel in its own right, but is also home to a graphite holy grail: the world’s oldest wood-cased pencil, which dates to the 17th century. On a more recent day the castle also housed its veritable king, the company’s leader and CEO, Count Anton-Wolfgang von Faber-Castell, who is speaking over lunch. “Thirty years ago I was worried that pencils would disappear,” he says candidly. “I’m much more optimistic now.”

At age 73, Count von Faber-Castell represents the company’s eighth generation of family leadership and wears his pedigree proudly; he has helmed one of the world’s oldest family-owned businesses since 1978. Since 1761, the company has grown to become a leading manufacturer of stationery products for writing, drawing, and creative design—including art supplies, craft kits, and even small leather goods—as well as makeup pencils for the cosmetics industry, and is one of the oldest industrial companies still in operation today.

As his company’s brand name is also his bloodline, Count von Faber-Castell is quick to credit his great-great-grandfather Lothar von Faber for setting Faber-Castell’s ambitious quality standard in the 19th century. As the current patriarch, Count von Faber-Castell has navigated muddy waters that included the economic downtown of 2008 and the onset of digitization. In this modern age, where a child handed a book may try to swipe the paper pages like a touchscreen, Faber-Castell’s success is proof that the power of the pencil has still got profitable clout; the company earns 590.4-million euros ($785-million Canadian) in gross revenue each year.

“In the 1980s, I chose not to invest in computer design for our products. Then, in the late eighties, our coloured pencils were introduced, and they saved us,” reflects Count von Faber-Castell. “The digital world is something in which we have to live, and I do believe there are some synergies, but with each step you have to ask, is it helping your business? Through time, I’ve realized there is always a need for a pencil.” It is a clear-headed value that has branded Faber-Castell with a work ethos that has endured centuries. “After all, family businesses tend to think in generations, not in quarterly earnings.”

For Faber-Castell, that heritage stretches back 253 years. Its first two generations presided over teams of craftsmen that made everything entirely by hand, before inevitably going the way of industrial production. The factory building that stands today was completed in 1928, and the castle—first built in the 1840s and finished in 1906—housed members of the media and lawyers during the postwar Nuremberg trials, and then was used by U.S. officers as a clubhouse until 1953. Today the building plays frequent host to conferences and special events in its beautifully restored art nouveau, classical, and gothic style rooms.

A five-minute walk south, to the Stein production plant, the setting is slightly grittier—it feels like high school shop class meets lumber mill. There are bundles of graphite stacked in crates, conveyer belts of pencils, and the scent of fresh cedar, most of which is sourced from sustainable forests in Southern California, as well as the Caribbean and Brazil; the graphite comes from Germany and Central Europe.

The Stein factory sets the standard for the rules and regulations that are applied to all of Faber-Castell’s global production facilities, which are located in nine countries spanning three continents and employing 7,500 workers. Manufacturing a staggering 2.3 billion pencils annually, Faber-Castell is the largest producer of wood-cased pencils in the world. Each plant has a specialty; the Peruvian plant specializes in children’s pencils, for instance, while the Malaysian factory turns out erasers in such abundance that Faber-Castell is the biggest global producer.

A basic Faber-Castell pencil goes through at least 10 production steps, and part of this process is open to the public to observe. On the factory floor, a woman eyes a conveyer belt while hand-picking specimens with irregularities that will later be donated instead of scrapped. Pencils are stacked alongside their colour-coded counterparts before they are moved to another area for the application of “grip dots”, a Faber-Castell mark of honour, with a patented laser technology. Rumour has it that when ballpoint pens with rubber grips were invented in the 1990s, the idea was taken from Faber-Castell’s grip dots.

“You need to do something different when companies produce the same product, and always be revolutionizing,” says Faber-Castell employee Siegfried Bloß. To that end came the Graf von Faber-Castell line, the brand’s luxury offering of writing instruments, which launched in 1993 with the slender, platinum-plated Perfect Pencil (with a brilliant built-in sharpener) and quickly expanded to the Pen of the Year line, coupling timeless design with precious materials like ebony and other pure hardwoods. “The idea came from a craftsmanship angle,” says Frauke Klotz-Willenbrink, Faber-Castell’s premium product manager. “We wanted to develop a product that was produced only for one year, and then never again.” It takes between six and eight months to finalize each collection; for each, around 2,000 units are produced (though it varies), and many incorporate materials that have never been used on pens before. Klotz-Willenbrink gives the example of Dorit Berger, a German artisan with a special hand-weaving skill, whose work turned up as the intricate, gleaming horsehair filigree pattern on the casing of 2009’s Pen of the Year. “She was the only one who could expertly weave over 72 hairs per centimetre,” explains Klotz-Willenbrink. With every element made in Germany, the Graf von Faber-Castell collection single-handedly earned the company membership to the nation’s Handmade-in-Germany manufactory initiative.

Another notably opulent line was created in recognition of the Queen’s Jubilee. The diamond-encrusted fountain pen was produced in a limited run of just 10 pieces and priced at 70,000 euros ($101,500 Canadian). For some, however, purity and perfection lie not in the high-end lines but with Faber-Castell’s renowned artists’ pencils. Notable fans have included Walt Disney, Karl Lagerfeld, Paul Klee, and even Vincent van Gogh, who professed his affinity for the pencils in a letter to a friend: “They are of ideal thickness,” wrote the artist in June, 1883. “Very soft and in quality superior to carpenter’s pencils, a capital black and most agreeable for work on large studies.”

Whittle Faber-Castell down to its carbon core and you’ll find a wide product range with a strong global reach, and the added twist of a rich family tradition. “I often think,” says Count von Faber-Castell, “similar to something Warren Buffett once said, that the most interesting business opportunities are not the ones that cause applause, but the ones that cause a yawn. And for us, that’s been true.”