-

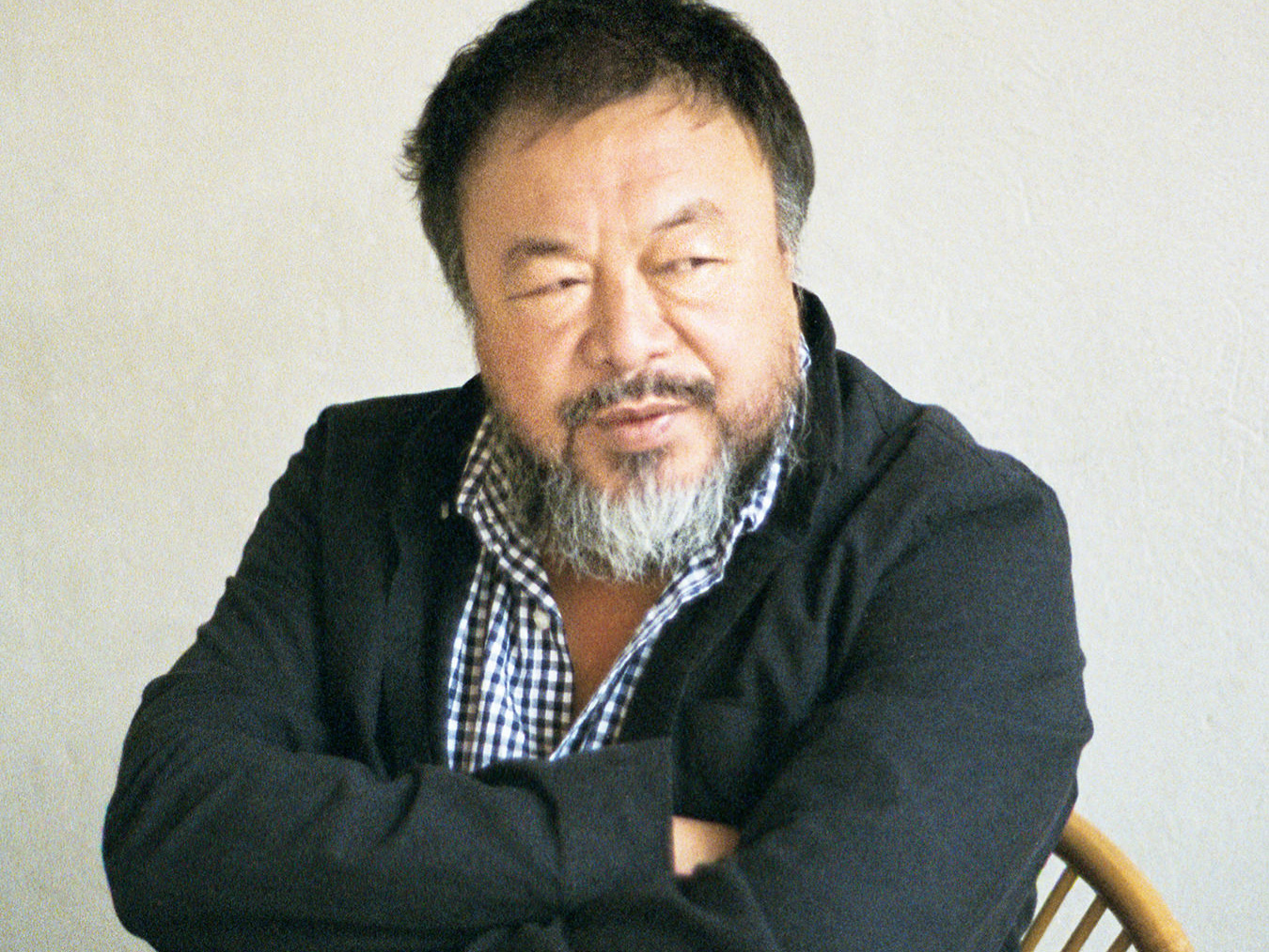

Jordan Porter sits in Wenjun Zhang’s kitchen, whose residence is located in Hongzhi, a relatively unknown village where Porter takes his clients to forage.

-

Peppercorns—a spice in the citrus family that imparts a numbing flavour—are a hallmark of Sichuanese cooking.

-

Porter leads guests up into the mountains to search for fresh herbs and vegetables.

-

“I want to cut through the parade of modern day tourism and show people the Chengdu I fell in love with,” says Porter.

-

The fruits of a Sichuanese forage.

-

Once prepared and rubbed with chili, Zhang smokes a chicken over an open fire.

-

A meal prepared by Zhang using local farm-to-table ingredients.

Chengdu Food Tours

Culinary wanders in Sichuan.

“There’s more to Chengdu than just peppercorns and spice,” Jordan Porter says, sipping a cup of fresh-steeped green tea.

We’re sitting in the middle of a park in the center of Chengdu, while locals all around us play mahjong with green tiles, and tall, grand stalks of green bamboo (some of the rarest species in the world grow here) provide shade.

“For one, this is a city of leisure,” he says.

Born and raised near Perth, Ontario, Porter is the owner of Chengdu Food Tours, a boutique food tour company in the capital of Sichuan, China. Located in the southwest, Sichuan is most often synonymous with spicy food (and pandas). But it’s also a province marked by its rich food forests, lush mountains, and rural Tibetan towns. Drawn to the sheer abundance of Sichuan, Porter moved to Chengdu in 2010 to take Chinese classes and ended up, serendipitously, in a cover band. “It was a bunch of white guys touring around Sichuan singing Chinese songs,” he reminiscences. “I played bass.” The band gave him income, an excuse to travel the province, and introduced him to his now-wife. What intended to be a one year stay ended up being a lifelong commitment. Today, he’s fluent in the language, conversationally adept at local dialects, and extremely well-versed in the food scene.

Porter is extremely conscientious of his place in Sichuan society. “The fact is: I’m an immigrant. The term expat … comes from a place of privilege. Moving here gave me a deep sense of appreciation for China. It was humbling and made me realize how much the West is constantly marginalizing Chinese food;” he says, adding, “I want to cut through the parade of modern day tourism and show people the Chengdu I fell in love with.”

Porter’s tours are mostly custom-tailored, depending on guests’ curiosities and tastes. While he prefers this method, he also offers a standard four-hour walking tour designed for those who want a quick primer into Sichuanese cuisine.

Opting for the former tour style, I tell him I have a particular interest in markets and ingredients, and he takes me through a local open-air bazaar where folks make their own liquor, dry their own spices, and brew their own doubanjiang, a spicy bean paste made with fermented broad beans and chili.

“I want to cut through the parade of modern day tourism and show people the Chengdu I fell in love with.”

“Er jing tiao is the main chili pepper here,” Porter explains. It’s a long and skinny cayenne pepper that’s relatively mild in taste. The chili pepper, he notes, is not native to China. “They came to Sichuan via South America,” he says. Portugal traders had introduced the chili pepper by way of the maritime trade route to Chinese coastal areas. During the Ming Dynasty, there was an attempt to repopulate the Sichuan Basin after a series of wars devastated the local population. Immigrants from these coastal cities then moved to Sichuan—which created the basis of the modern Sichuan cooking.

Sichuan, as Porter will attest, is a true melting pot; it’s rich in both regional dialects and food. “Leshan has amazing beef; Zigong has the spiciest food in all of Sichuan,” he says, highlighting the province’s diversity.

And while Porter’s tours revolve mainly around the city of Chengdu, he does offer a countryside tour to a small, relatively unknown village called Hongzhi, where folks can forage for dinner and barbecue a farm-fresh chicken.

On one such tour, Porter takes me to the home of Wenjun Zhang, a cheery young farmer whose residence is perched up on narrow roads amidst mountains and thick vegetation. We spend the entire day there. Lunch is stewed peas, cured pork, stir-fried wild vegetables, and homemade spicy sausage spiked with local peppercorns. Peppercorns—a spice in the citrus family that imparts a numbing flavour—are a hallmark of Sichuanese cooking.

For dinner, Zhang takes us for a trek into his local forest and we forage for wild things—goosefoot (a quinoa relative), wild celery, and the spicy zhiergen rhizome. This is our dinner and it’s supplemented by a fresh chicken, smoked over wood and marinated in chili.

Porter takes the reins on the grill, cutting off pieces of the chicken for our indulgence. It’s meant to be eaten immediately. “There’s something so comforting about barbecue,” he says. “It doesn’t matter what culture you’re from or where you come from. Eating grilled meat over a fire is universal.”

And so I feel somewhat at home, in Hongzhi.