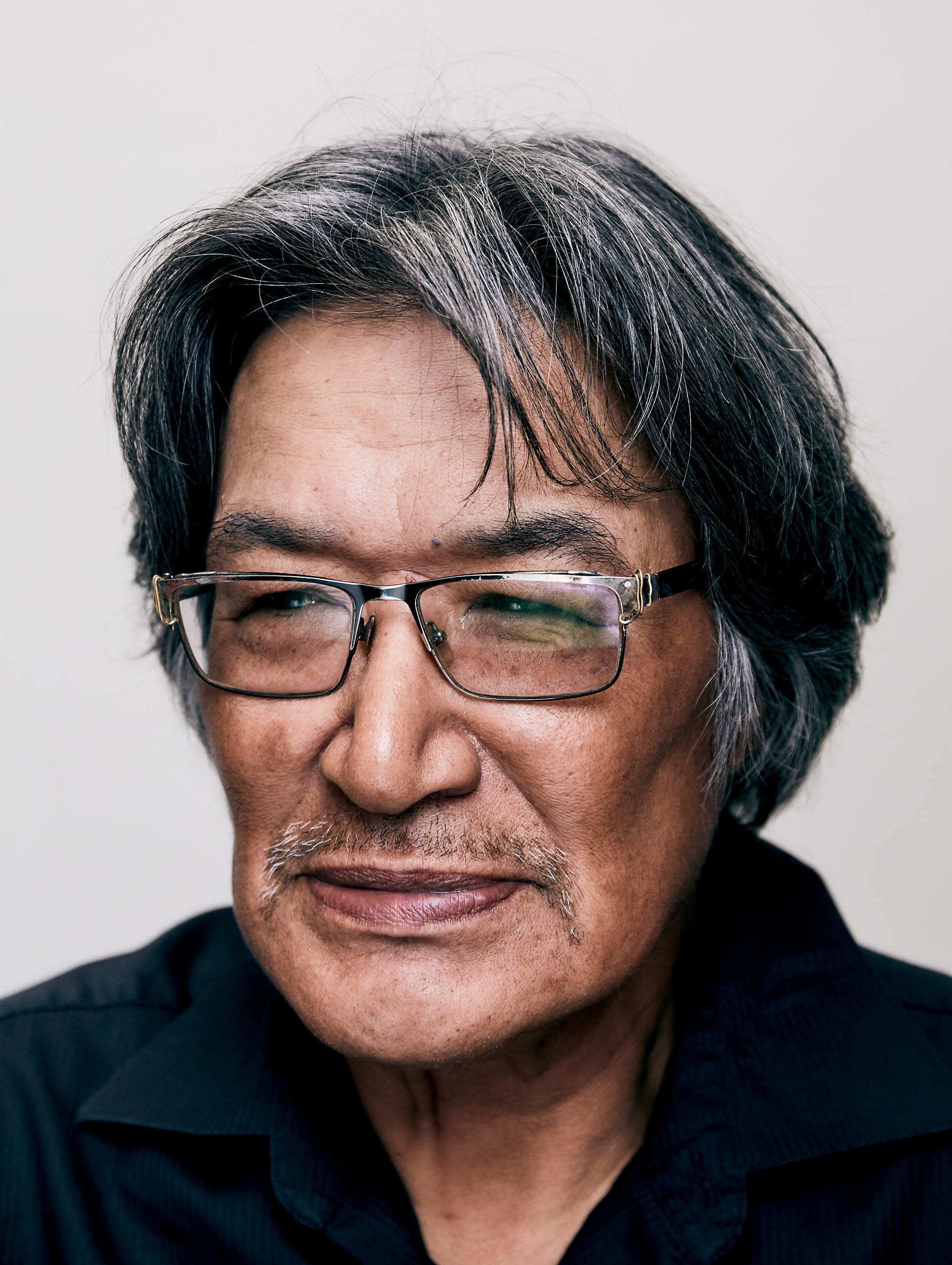

Zacharias Kunuk on Carrying the Tradition of Inuit Storytelling Through Film

Poignant stories of Artic life.

Photo by Luis Mora in TIFF X Samsung Studio. Courtesy of Toronto International Film Festival, 2019.

Enthralled by the stories of his fellow Inuit, Zacharias Kunuk fondly remembers being lulled to sleep by his mother telling him folk tales. When he awoke, his first thoughts were about what happened next.

The award-winning filmmaker, who has dedicated his career to storytelling, has now created another poignant story of Arctic life with his latest tale for the big screen: Angakusajaujuq: The Shaman’s Apprentice. In this stop-motion animated short in Inuktitut with English subtitles, a young woman faces her first test as a healer and must visit Kannaaluk, the One Below, to help an injured young hunter while being guided by her grandmother. Set in Kivitoo on northern Baffin Island, the film explores the Inuit belief that illness is related to breaking a rule, such as disrespecting a person or animal. “I first heard the story from an elder in the 1980s,” explains Kunuk, who co-produced the film with Iqaluit’s Taqqut Productions. “I was interested in showing the journey to the underworld.”

The director of the greatest Canadian film ever made, Zacharias Kunuk stays out of mainstream. From his home in Igloolik, the filmmaker focuses on Inuit stories.

This isn’t Kunuk’s first attempt at stop-motion animation, which he feels is the best medium to showcase Inuit folk tales as it is less limiting than traditional film. Still, “the first time, I didn’t like it,” he says. “But I’m always trying to experiment.” He persisted, finding success working with animation director Evan DeRushie, who welcomed Kunuk’s passion for details. “I visited the producers twice, showed them how dog sleds are built, bringing them examples of sled dog harnesses and making sure the clothing details were correct,” Kunuk says. It’s those small details, like the addition of traditional tattoos on the young shaman’s face, that make this film even more of a treasure for preserving Inuit culture.

The film portrays the characteristics of the Arctic that have become hallmarks of Kunuk’s screen projects. The soundtrack, overseen by Beatrice Deer, conveys the story’s isolated settings by mixing the sounds of sled dogs and snow sleds with the gentle melodies of Inuit songs. There’s the constant wind, steadily moving the fringe on the characters’ clothing, a gentle reminder of the harsh yet familiar weather for those who live beyond the tree line. The use of light contrasts the stark brightness of the outdoors reflecting the snow-covered landscape to the dim interiors, lit from the glow of a fire tended by the grandmother.

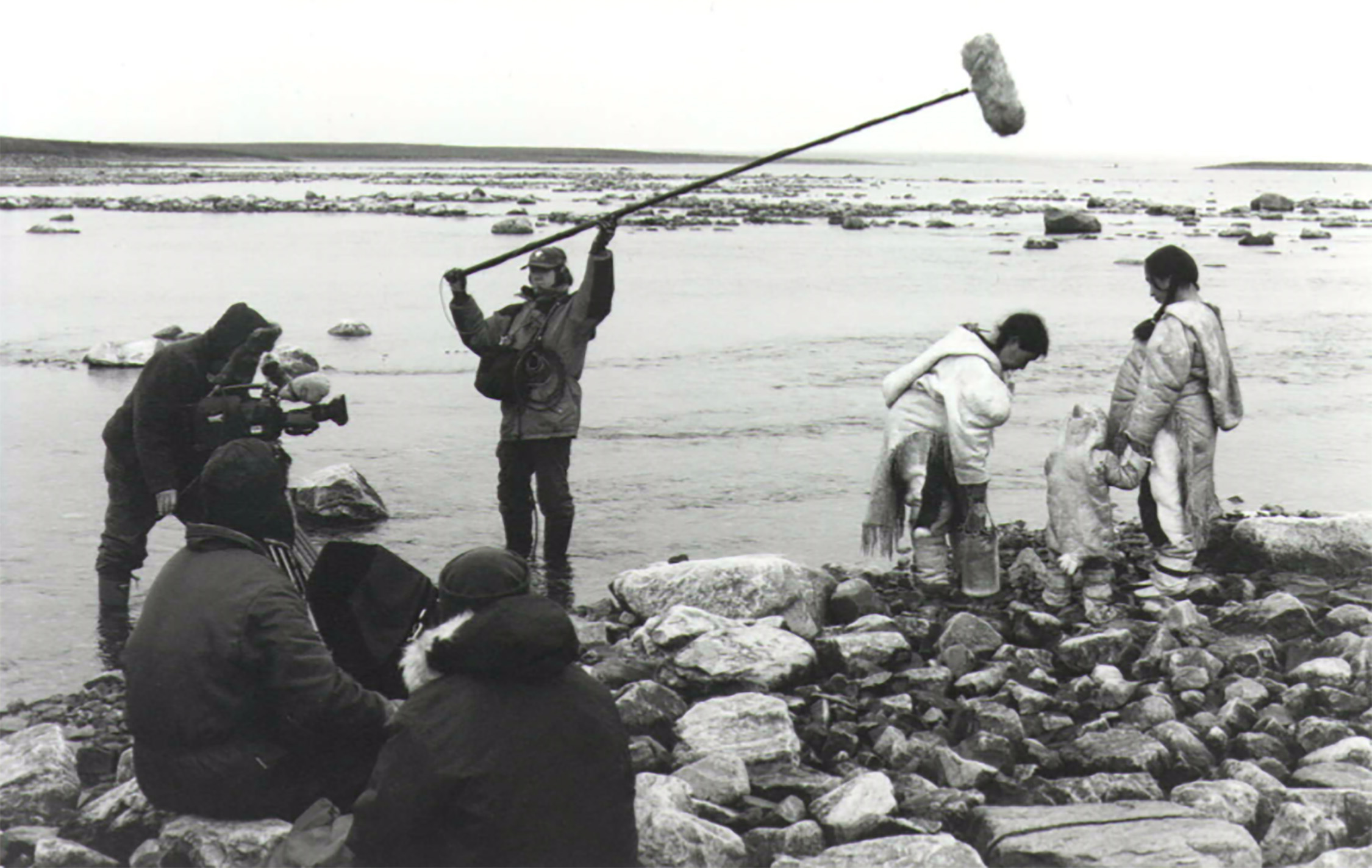

On the set of Atanarjaut(The Fast Runner).

The film palette is neutral with colour used sparingly. Living north of the Arctic Circle, Kunuk once again draws on a landscape without trees and high-rises, highways or fast food chains, an idyllic northern paradise in jeopardy from Christianity, government, and corporations.

Angakusajaujuq had its North American premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival, winning the 2021 IMDbPro Short Cuts Award for Best Canadian Film along with a $10,000 bursary. The film was also honoured this past June with the FIPRESCI Award at the Annecy International Animation Film Festival in France.

“A hundred years from now, when we’re long gone, people will study these films. We’re trying to get the history correct to show what happened to us.” —Zacharias Kunuk

As a filmmaker and Indigenous artisan, Kunuk has been a regular in the winners circle since his 2001 debut feature film Atanarjuat (The Fast Runner). It was the first Canadian feature film completely in Inuktitut, and Kunuk was the first Inuk to direct a film with an entire Inuit cast. The screenplay he co-wrote was inspired by a folk tale with contributions from eight elders.

Roger Ebert gave Atanarjuat four stars, saying the film tells a universal story: “The Fast Runner is passion, filtered through ritual and memory.” Kunuk became the talk of film critics worldwide, as Atanarjuat won the Caméra d’Or for best first feature at the Cannes Film Festival, was ranked the greatest Canadian film of all time by TIFF filmmakers and critics, and received six Genie Awards.

An actor studies notes on the set of The Journals of Knud Rasmussen.

A writer, director, and producer, Kunuk has also worked as a cinematographer, art director, and editor on his own productions as well as executive producing several projects with fellow Indigenous filmmakers. He makes his home in Igloolik, an island north of the Arctic Circle and far from the red carpets of Hollywood, New York City, and Toronto. “I’m far out of the mainstream,” he says. “I don’t follow the trends.”

From an early age, Kunuk bought film cameras, teaching himself how to use them through trial and error. When he and his family moved to a settlement on Baffin Island in the late 1950s, he remembered his obsession to see movies, especially those starring cowboys. “I was carving soapstone to sell the sculptures to teachers, hoping to earn money to go to the movies,” he says.

Learning the point of view of filmmaking from many vantage points but without formal training, Kunuk started his career by using money from selling sculptures on a trip to Montreal to buy and bring a video camera back to Igloolik. When he was hired by the Inuit Broadcasting Corporation in 1984, he met Norman Cohn, who would go on to produce, co-write, and operate the camera for Atanarjuat. The two, along with Paul Apak Angilirq and elder Pauloosie Qulitalik, launched Igloolik Isuma Productions in 1990, the first Inuit-owned production company.

Isuma was selected to represent Canada at the 2019 Venice Biennale, the first time Inuit art had been shown in the Canada Pavilion. Kunuk’s feature, One Day in the Life of Noah Piugattuk, is the true story of Inuk hunter Piugattuk, played by Apayata Kotierk, faced with being forced by the Canadian government to assimilate. “A hundred years from now, when we’re long gone, people will study these films. We’re trying to get the history correct to show what happened to us,” Kunuk says.

“Indigenous people have gone through a lot,” he notes. “We’ve lost our stories and songs to Christianity. Our elders’ belief system changed. Our young people have lost their identity. Even though we don’t want to, we have to listen to the white man.”

When Kunuk was growing up on Baffin Island, the Church banned storytelling in an attempt to erase the local culture, but he knew the thousands of years of knowledge, experience, and tradition wouldn’t disappear. He wanted to make sure subsequent generations could discover the fables, using visual mediums within film and television to make sure they’re heard far and wide.

“I grew up within a culture that didn’t have books—our oral tradition was how we shared our knowledge, history, and stories,” he says. Although shamanism was rooted in Inuit culture, the teachings of Christianity made it seem like a sin. Thankfully, the older generations of Inuit are slowly returning to the old ways, Kunuk says, and the younger generations can learn about shamanism with pride. “Lucky for me there are several elders still living, willing to share the stories of what was happening: what was the white man and what did he want?”

Maliglutit (2016) is based on the John Ford film The Searchers.

In recent years, Kunuk has shared more Inuit stories on the big screen: The Journals of Knud Rasmussen (2006), which earned him a best director award at the American Indian Film Festival; Sirmilik (2011), which won the Genie for short documentary; Maliglutit (2016), based on the John Ford film The Searchers starring John Wayne; and Kivitoo: What They Thought of Us (2018), a documentary about a Baffin Island community that was relocated by the government and never returned home. He’s been executive producer on feature films, documentaries, short films, and television, using the different ways to explore Inuit culture and share the detrimental effects of colonization and government policy on his people.

Next up is a documentary project titled Duty to Consult, about the controversial proposed expansion of a mining development on northern Baffin Island. He’s also written an illustrated version of The Shaman’s Apprentice with drawings by Megan Kyak-Monteith and published by Inhabit Books. Available in Inuktitut and English, the book includes a glossary of Inuktitut words and a pronunciation guide. It’s another example of how Kunuk perseveres by using art to share and preserve the stories of the Inuit as well as showcasing wholly Indigenous-created art.