Architect Mariam Kamara, Under the Mentorship of Sir David Adjaye, Created a Cultural Centre in Her Native Niamey

Guiding light.

Mentor Sir David Adjaye and protégée Mariam Kamara visit the regional market designed by Kamara in Dandaji, Niger. Credit: ©Rolex/Thomas Chéné

For novelist William Faulkner, architecture was like the furniture of time. Over time, the furniture gets rearranged, reupholstered, and when necessary, changed. The architect plays the vital role of both cordial convenor and custodian of the spatial contract. We call on architects to imagine spaces and change our habits.

Hashim Sarkis, curator of the 17th International Architecture Exhibition and dean of MIT’s School of Architecture, posed the question “How will we live together?” for this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale, for which Rolex is an exclusive partner and the official timepiece. “We share a need for perfect function,” Sarkis says of the partnership. “You [Rolex] measure time, and in measuring it, you actually create it,” he commented during a dinner at Ca’ Giustinian. “We [architects] measure space, and by measuring, we create it.”

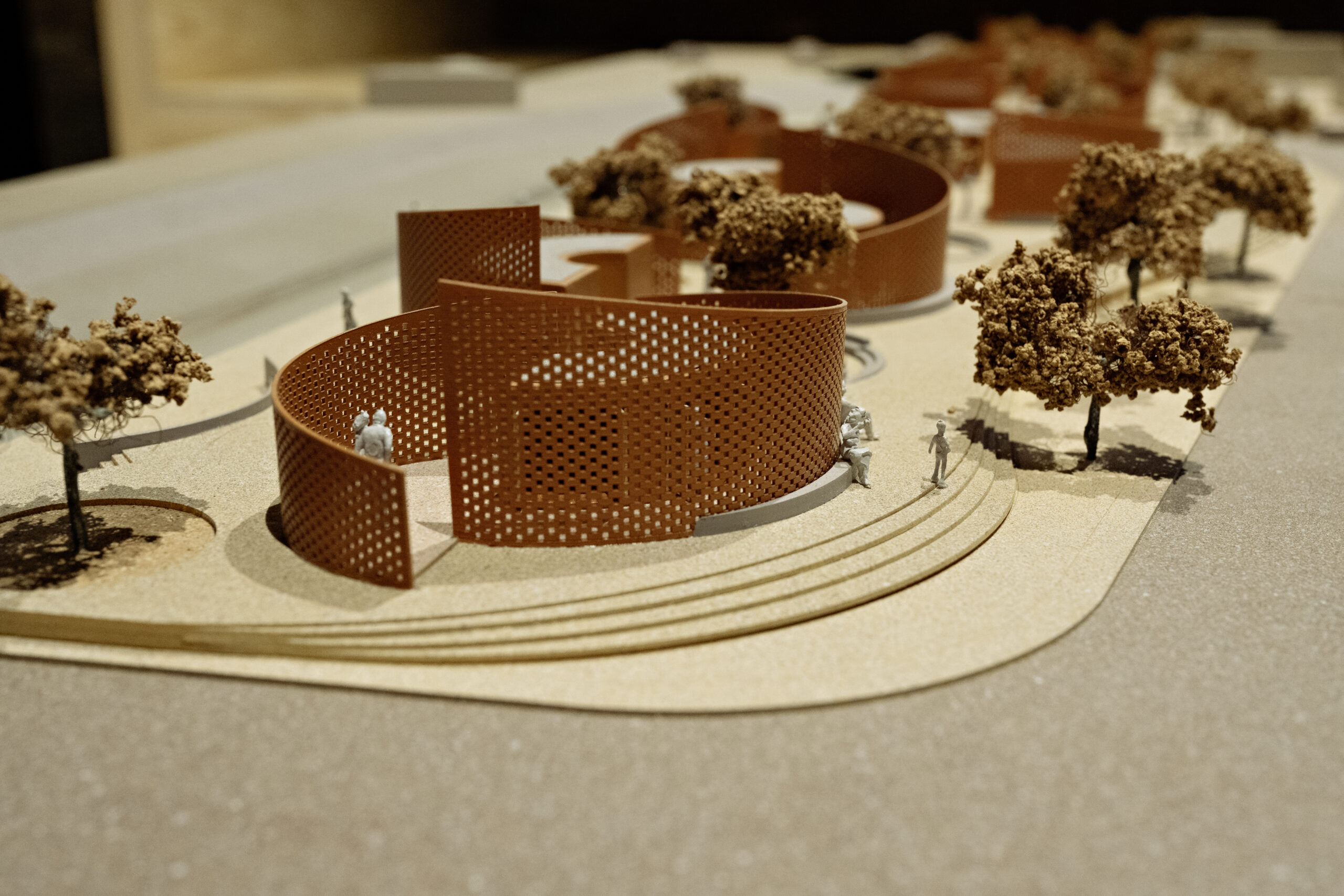

The towers of the Niamey cultural centre, made from traditional materials used in local architecture, provide natural shade and ventilation. Credit: ©Rolex/Reto Albertalli

Rolex’s formal relationship with the biennale is well-established, but the Rolex Pavilion in the Giardini does not represent a country like those around it. The structure, which recalls the fluted bezel signature of a Rolex timepiece, is where architectural projects are presented and is a platform for the Mentor and Protégé Arts Initiative. Responding to the theme announced by Sarkis, architect Mariam Kamara, under the guidance of Ghanaian British architect Sir David Adjaye, created a cultural centre in her native Niamey, the capital of Niger. The building is in the Gounti Yenna Valley, which historically divides the French colonial part of the city where local elites reside from that of the economically disadvantaged. Kamara hopes the centre will encourage disparate societal groups to come together.

The Rolex Mentor and Protégé Arts Initiative is based on the traditional concept of mentoring in the arts. Since 2002, masters in theatre, dance, music, visual arts, literature, film, and architecture have worked one-on-one with young artists, helping them realize their full potential. Architecture mentors have included Kazuyo Sejima, Peter Zumthor, Sir David Chipperfield, and Álvaro Siza.

Since completing her master of architecture at the University of Washington in 2013, Kamara has based her practice Atelier Masomi in Niger, “because I wanted to prove to myself that this is possible,” the 42-year old architect says. “I want to make a point that Africa is not just geographical beauty you see on National Geographic, but actually we contribute to the world in terms of skills and spirit.”

Mariam Kamara at the Rolex Pavilion and Exhibition.

From the Exhibition of Mariam Kamara at the 17th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia.

The Niamey project uses traditional materials from the local Hausa and Songhai architecture styles along with a system of convex towers that shade and allow ventilation (avoiding use of air conditioning). “It was very much about speaking to the residents of the city as to what was needed,” Kamara says of the cultural hub. “We are a culture who lives outside most of the time, and how do you protect that, how do you shape that? As a cultural exercise, it was very pragmatic: I want to use walls to create shape, but the spaces are really wide so the walls have to be taller and taller and taller.”

This is how programs like the Rolex Mentor and Protégé Arts Initiative make a difference. “It is an incredible gift that Rolex has made in the world, this idea of protégé,” Adjaye says. “As one gets successful in their stream of work, one wants to reach out to the younger generation, but it is sometimes difficult to do. One can teach, but really what you want to have is the one-on-one.”

For Kamara, the mentorship was a confidence booster. “I remember our meeting in London,” she says of her initial encounter with Adjaye. “Our conversation was validation of what I was thinking, of what I was hoping for in terms of the work I want to do. And then when David came to Niger, then everything unlocked, he wanted to see my universe.”

Sir David Adjaye and Mariam Kamara.

When Rolex approached Adjaye to be a part of the initiative, he specified, “I want to help young architects in Africa.” Rolex puts together a nominating panel, but it is the mentors who choose. “In seeing Mariam, I was struck immediately by the potential in what she was doing,” Adjaye says. “This is a young architect deeply interested in the continent of Africa, grappling with what is the idea of architecture. A lot of young architects on the continent think that success is to just come to the West, to succeed out of their own context. I was struck when I saw Mariam’s portfolio and I spoke to her. There is this incredible desire to work with exactly what she found in her country and to dignify that.”

Rolex’s founder laid the foundation for the company’s relation to architecture over 100 years ago with this mantra: Good-quality work can only be done in good-quality spaces. Giving guidance, imparting wisdom, and sharing experience is the base on which the Rolex mentoring program was conceived and continues to operate. Adjaye and Kamara have created, they have learned, and they have shared. “Mariam is one of the spearheads of a rethinking renaissance of what the built environment, of what a continent can be for the emerging African citizens and their contribution to the idea of architecture,” Adjaye says. “This idea of moving away from a singular trajectory to a decolonized, much more horizontal knowledge base which allows for flowering is the world we are all wanting. Essentially, we don’t want a world that looks the same.”