George Sully Was Canada’s Most Unsung Successful Fashion Designer. Then the World Woke Up.

Steady footing.

George Sully’s career as a Canadian fashion designer has had many chapters, but two are more significant than the others: before June 2020 and after. Sully wasn’t doing anything in June 2020 that he hadn’t been doing in June 2019 (or many Junes prior). It was the world that changed around him. And it was, he says, a long time coming.

“I’ve had so many wins in this industry over my career, but I feel like there’s been a ceiling,” says the Toronto-based founder of accessories brand Sully & Son Co. and a two-time inductee to the Bata Shoe Museum. “If you look at my career as a whole, and then at the last year, it’s like I caught up on all of the opportunities I didn’t get.”

The reason, Sully says, isn’t personal. It is an example of the systemic racism that has kept BIPOC from succeeding in the fashion industry at the same level as their white peers. It is a system he was glad to see take a major hit in the summer of 2020 when the Black Lives Matter movement sparked protests around the world, and businesses, governments, and individuals across Canada embarked on the process of becoming more inclusive. Not only did it mean an unprecedented reckoning about how BIPOC are treated in our society, it meant George Sully finally had a seat at the table.

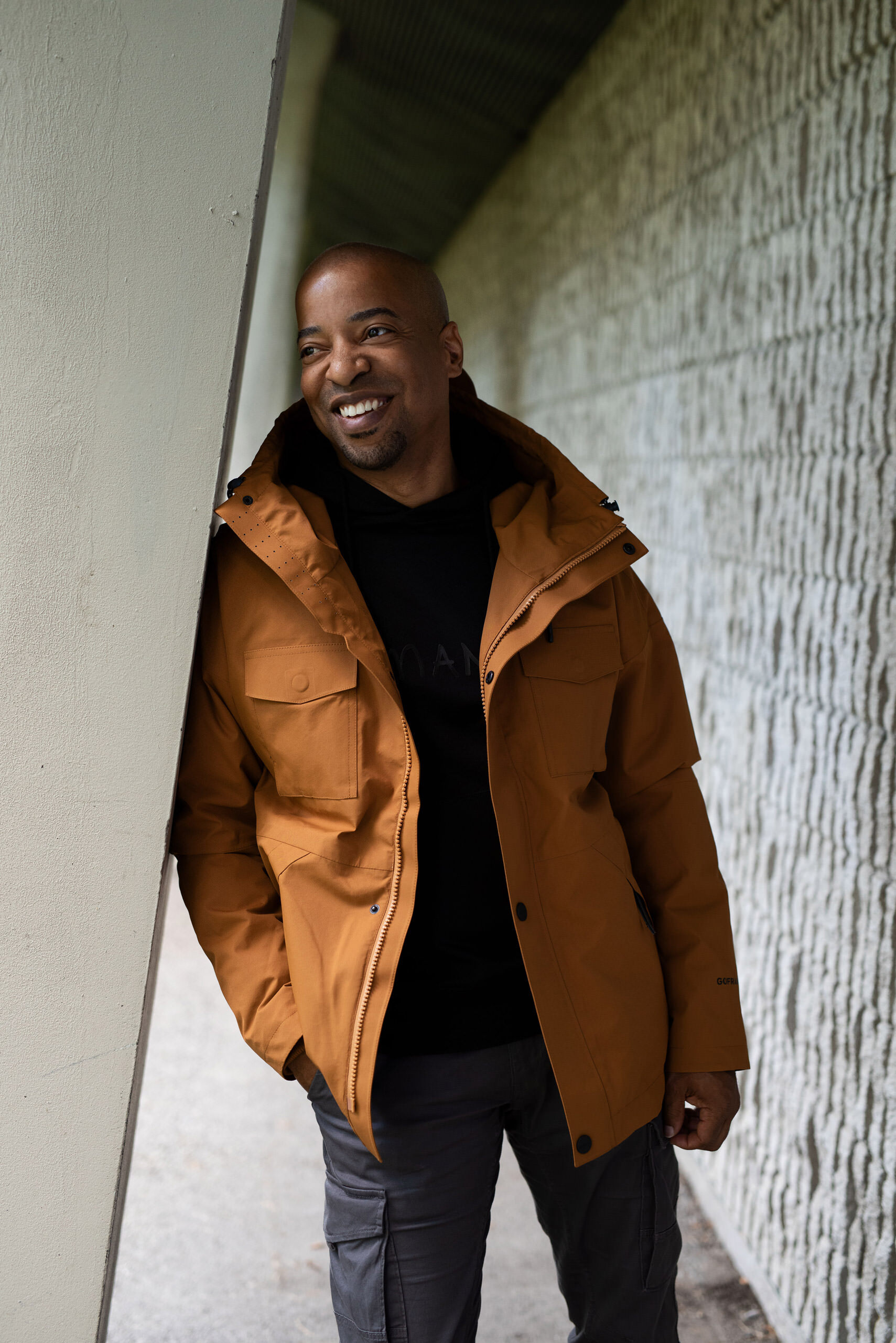

Sully wears a Gofranck Jacket and Sully & Son Co. Shoes.

“Look, I didn’t get any better after June 2020, but all of a sudden I start to get these meetings and opportunities to showcase my wares,” he says. “They saw my stuff, and they’re like, ‘This is amazing!’ It blew them away. This is what I’ve been talking about. Just get us on the floor and let us compete. We will win or we’ll fail, but you have to give us that lane where we can run with everybody else.”

Sully grew up in Ottawa in the 1990s, drawing creative inspiration from his mother, a painter, seamstress, and chef, and his father, a jewellery designer, sculptor, and illustrator. When Sean “Diddy” Combs founded his fashion brand Sean John and won the prestigious Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA) award for Menswear Designer of the Year shortly after, Sully, an aspiring DJ himself, began to imagine a career in fashion. He moved to Toronto and launched the streetwear brand Limb Apparel, whose logoed tees and sweats earned endorsements from some of the era’s biggest celebrities, fashion shows in Miami, and distribution through Athletes World, then a major national sportswear retailer.

“I thought I was going to be the next Diddy,” Sully recalls. “At the time, I had supporters like Paris Hilton, Lil Jon, Kid Capri, Fall Out Boy. … I never had a problem with customers or fans of the brand. It was the system that refused to let me in and celebrate success that looked like me.” The bigger the brand got, he says, the more it felt the system was holding him back. “That’s the thing with systemic racism: it’s like carbon monoxide. You can’t see or smell it, but it affects us all deeply, and some don’t come back from it.”

Sneakers from Sully & Son Co.

Buoyed by the success of Limb Apparel, Sully’s next move was Sully Wong, a footwear and accessories brand he co-founded with Henry Wong, which was soon picked up by big-name retailers across Canada and internationally. Here, Sully focused on design, honing his minimalist, futuristic aesthetic and collaborating with names such as Canadian designer Karim Rashid, Nobis, CÎROC, and the ONEXONE foundation on limited-edition sneakers. Then, in 2018, Sully won his biggest bid yet, the opportunity to design and produce a costume boot for a new Star Trek spinoff on CBS. The Starfleet boot would earn Sully Wong wide recognition and praise. “It meant a lot,” he says. “It’s something I like to refer to as legacy work—something my son can be proud of when he’s older.”

“As industries become more inclusive, myself and other designers of colour can continue to do what we do best and create with no limitations or boundaries,” George Sully says. “In this new world, there’s enough for everybody, and it shouldn’t matter who goes first.”

By the time the pandemic hit in early 2020, Sully had moved on to new projects, like Sully & Son Co., a line of black-on-black waterproof backpacks and messenger bags with built-in USB charging ports. “The brand represents all of my expertise and experiences over the years wrapped up into one tight package,” the designer says. With his partner, Hayla Amini, he also co-founded House of Hayla, a colourful women’s footwear brand, and created Shoeonado, a brand that puts Sully’s decades of experience in sourcing, marketing, and design to work creating footwear collections for private label clients.

The Mausu Minipack from Sully & Son Co.

Things were good for Sully before the pandemic, but after watching for years as white colleagues surpassed him with big-name campaigns and big-volume orders from retailers, he couldn’t escape the feeling that things weren’t as good as they should be. “These are my friends, and they have gotten so much more opportunity than myself,” he says. Success, of course, is by no means guaranteed in the fashion business, but something wasn’t adding up for Sully. In June 2020, amid the riots, protests, and Black Lives Matter murals appearing on city streets around the world, he seized the opportunity to make himself—and Canada’s many other unsung Black designers—part of the conversation.

“I Googled ‘Black Canadian designer,’ and all I got was like two articles, and they were both geared towards Black History Month,” Sully says. “And then, it went into black carpets, black cats, black—anything else. Two articles, and that’s it.” He knew there were many more Black designers in Canada, and he knew the specific challenges they faced getting noticed, and he decided to do something about it.

A duffel from Sully & Son Co.

Sully founded the online database Black Designers of Canada in summer 2020 and put the call out for his fellow designers—in fashion, interiors, web design, graphic design, and other fields—to stand up and be counted. The website now features nearly 200 Black Canadian designers across a wide spectrum, from high-end-furniture maker Augustus Jones to Toni Marlow, a queer-positive underwear brand. “If you’re making a conscious effort to get a BIPOC brand or a Black designer, this is the place where you going to go,” he says. “It’s world-changing for designers who have only had their own small network before. This is the first time they’ve been acknowledged outside of that, and now they’re getting picked up for film, commercials, everything. It’s huge.”

He also put out calls for nominations for the Black Designers of Canada Award of Excellence and handed out over 100 engraved glass statuettes in February 2021. “I was making a point that 90 per cent of these designers should have been celebrated already,” he says. “They would have already gotten their push and their acknowledgement, because these are amazing brands, and we’ve been here the whole time.”

Another round of statuettes are in the works to be awarded in February 2022, and thanks to new partnerships with DHL, Salesforce, Holt Renfrew, and Sezzle, Sully now has a whole new tool kit of resources to offer his fellow Black designers, from help setting up webinars to a DHL concierge service to assist with shipping their wares. It’s a small start, but Sully sees it as an indication of things to come. “As industries become more inclusive, myself and other designers of colour can continue to do what we do best and create with no limitations or boundaries,” he says. “In this new world, there’s enough for everybody, and it shouldn’t matter who goes first.”

With Sully & Son Co. selling briskly at the Bay and Harry Rosen, plus countless other private label projects and pitches in various stages of development, Sully finally feels like he has an open lane to run in. After spending almost 20 years learning how to do things the hard way, he finally feels he’s competing on a level playing field for the first time. “I just want to reach my full potential without systemic interference,” he says. “It’s a long shot, I know, but still, I just want to race. No advantages necessary, just equal placement at the starting line, so win or lose I can show the world what I’ve got. Just like everyone else.”