Richard Ginori’s Renaissance

The epitome of fine porcelain.

For more than two centuries, Florentine porcelain-maker Richard Ginori has produced singular, handcrafted tableware.

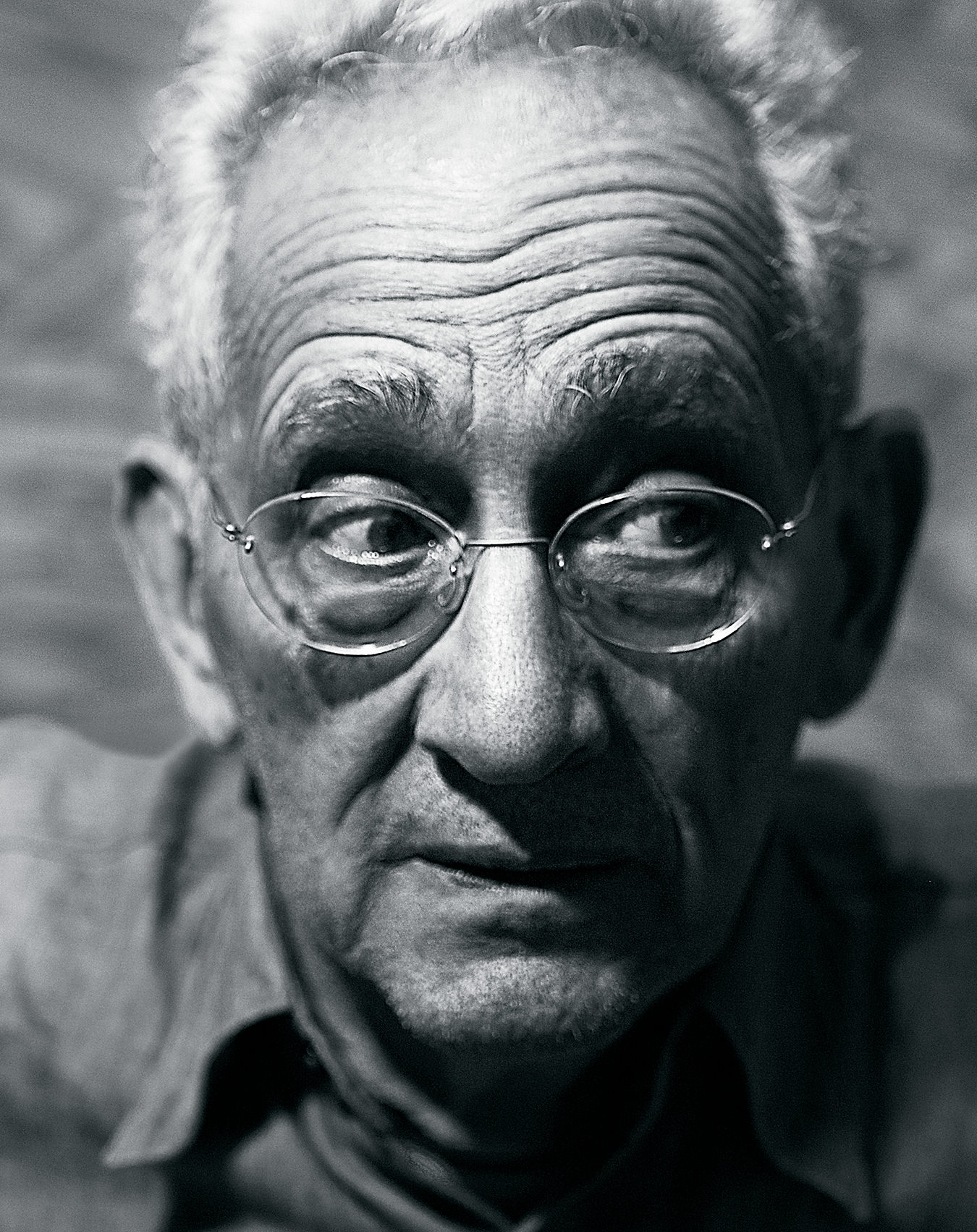

Marcello Bongini speaks of his profession as one would a great love. He has spent the last 42 years employed at the Richard Ginori factory in Sesto Fiorentino, a municipality 12 kilometres from the centre of Florence. Bongini is animated as he describes his time with the storied porcelain manufacturer; his accent is a dead giveaway that he is a local, as he speaks with a Tuscan throat. For nearly 300 years, the factory has produced singular, handcrafted, and elegantly decorated porcelain tableware. “A love story was sparked here,” says Bongini, and the implication is twofold. He has a deep affection for what he creates, but this is also the place where he met his wife. “Matters of the heart,” he says as he grins. “Gets me every time.”

Ginori pieces have long graced museum collections and the tables of the world’s wealthy and aspiring middle class. In 1735, the Florentine marquis Carlo Ginori founded a porcelain factory on his estate. He established Ginori as the pre-eminent producer of Italian dinnerware. His familiarity with chemistry and mineralogy, the discovery of clays in the Tuscan hills, and his fascination with art provided the impetus for the early Ginori work. Primarily destined for the Medici court, Ginori bore the mark of the dome of Florence’s Santa Maria del Fiore cathedral. Early works made under the direction of the company’s founder included the Granduca Coreana and Italian Fruit patterns along with a goblet for Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici, the last direct descendant of the Medici family. Ginori porcelain continued to be sought after by Europe’s noble families; grand services were produced for Austrian archduchess Marie Louise, Napoleon’s second wife. (The Napoleonic Wars forced the closure of many Italian businesses and saw Tuscany annexed. Despite this, the Ginori factory continued production, diplomatically adopting an Empire theme for its wares.)

The Orientale Italiana collection.

Ginori remained under family control until 1896, when, needing to expand, it joined forces with Augusto Richard’s Milanese ceramics factory, hence its name today. Over the years, the company enlisted top-notch designers, most notably Gio Ponti as artistic director from 1923 to 1933, who overhauled the production range and prepared it for serial manufacturing. Ponti set a more contemporary tone for the company and ushered in Richard Ginori’s acme of success; during that period the company employed 2,000 workers.

Bongini was 15 when, in 1974, after two years of apprenticeship, he began working as a workshop boy with Richard Ginori. “Back then,” he recounts, “Richard Ginori had within it a vocational school. The first year was spent learning the technique, while the second was guidance to major in one of the two creative sectors: modelling and decoration.” Directed by mentors, Bongini began working in the modelling department. Even today, at 57 years old, Bongini’s deep respect for his work can easily be read on his face as he tells of the difficulties of working with pure porcelain.

For nearly 300 years, the Richard Ginori factory has produced singular, handcrafted, and elegantly decorated porcelain tableware.

Porcelain is traditionally grey, but Richard Ginori porcelain is the whitest available (even whiter than Limoges). It consists of three minerals: approximately 50 per cent kaolin (the white clay that lends the plasticity needed for moulding); 25 per cent quartz (constituting the frame of the object, preventing it from altering due to heat); and 25 per cent feldspar (forms the vitreous mass that hardens the porcelain). These are milled and mixed together; water is added and the piece moulded. Then the piece is subjected to two stages of firing. The first, to consolidate the body, and the second (carried out at a temperature of 1,400°C), to vitrify the paint that covers it. Decorated porcelain requires further firings, the number varying according to the complexity of the decoration.

The Babele collection consists of 65 pieces—plates of all kinds, bowls, teapots, and vases—which recreates the floringatura effect, evoking 18th-century serial decorations.

Indispensable to the process of modelling is the sketch. “Equipment can be bought, and once no longer functioning, rebought,” says Bongini. “But the work of the hands and the thoughts of the human head, that can’t be bought.” Upon entering the factory, one sees a handful of designers in the modelling room stationed at large wood-and-marble tabletops in and among a sea of works in progress—frescoes, statuettes, vases, plates—the objects are numerous, the colour is uniform: white.

Designers must take into account two factors when determining the shape and size of a model. First, the shrink, as porcelain loses 15 per cent of its volume when fired, and second, softening—minimal structural changes generated as a result of the high temperatures of firing. A negative cast is created from the model into which is poured a mixture of very hard plaster that gives rise to the so-called “jet”. From this jet are created all the forms from which the wares are produced.

Bongini leads the way to the Voltone, the vault, what he calls “the historical memory of Richard Ginori,” where in an expansive concrete structure located directly above the furnaces, the moulds (some of which make up to 100 parts) of all the pieces the company has made from 1735 to the present are stored. Bongini estimates there are some 10,500 moulds, pointing to the handwritten ledger where each is catalogued. “We are very modern here,” he jokes. “It takes longer to input the information into the computer—we tried.”

Richard Ginori has two boutiques worldwide: Florence and Milan.

While Richard Ginori thrived for many years, producing handcrafted products for palazzos and luxury liners, as well as the Vatican, by January 2013 it was in bankruptcy. How a company founded almost 300 years ago—and having withstood numerous revolutions in industry and popular taste—went bankrupt is the subject of considerable debate. Formal dining has gradually been dying out, and with it the market for handmade porcelain, which is painstakingly slow and expensive to produce. (Many storied brands—Wedgwood, Spode, Rosenthal—have similarly been unable to survive in a market flooded with cheaply produced, utilitarian tableware.) Richard Ginori faced a choice between trying to preserve its status and market as a high-end niche product with Made-in-Italy cachet, and appealing to the broader, less expensive tastes of a global marketplace. It chose the latter and began producing more everyday products (including tableware for a promotional giveaway for a supermarket chain), putting the company in direct competition with more commonplace ceramics. “It became a numbers game,” notes Bongini. “Once you start making tableware for a lower target, you degrade the product.” This sentiment is what many employees blame for the company’s decline. The furnaces were turned off, save one small oven, and Bongini was one of only three employees retained to fulfill orders from Japan (Ginori’s largest market).

Richard Ginori’s saviour arrived later in 2013, when Gucci stepped in and took ownership. It injected much-needed capital, and a then little-known designer, Alessandro Michele, was drawn from the ranks at Gucci to oversee the new production at Richard Ginori, selectively pulling designs from the archives and reinterpreting them for modern living.

Richard Ginori, founded in 1735, continues on in the centuries-long tradition of excellence.

Since becoming the creative director at Gucci in 2015, Michele’s collections have radically redefined the label. Working within the historical parameters of the brand, where he had already been for over a decade, he has managed to integrate the symbols of the Gucci heritage into his eclectic and romantic vision, bringing emotion back to the brand. With an appreciation for the handmade and slightly eccentric, his version of Gucci is Old World meets modern woman (and man). And while creating the wildly successful new look at Gucci, he contemporized Richard Ginori as well.

Richard Ginori pieces have long graced museum collections and the tables of the world’s wealthy.

Michele began by reintroducing several Gio Ponti designs—the graphic Catene and Labirinto, with their stylized spin on geometric classicism, and the wildly popular Oriente Italiano, Ponti’s exotic 1926 image of a chinoiserie-embellished carnation, in a rainbow of 10 colours. There is a sense of antiquity and modernity, of the refined and rustic that runs through the current tableware. Some new collections Michele introduced for Richard Ginori include Babele of 65 pieces—plates of all kinds, bowls, teapots, and vases—which recreates the floringatura effect, evoking 18th-century serial decorations as well as Insetti, which includes a wide variety of accessories hand decorated with small animals and insects with symbolic associations—butterflies exuding a sense of spiritual transformation; the scarab, emblem of life and rebirth; the flying deer, symbol of good health; the cicada, archaic representation of immortality; and the grasshopper, a good luck charm. A new category has been the introduction of candles, a collaboration between Richard Ginori and Sileno Cheloni, the Florentine perfumer. With a strong footing in the new Richard Ginori spirit, the internal design team continues on in the manner Michele has guided.

The maker’s mark.

With Richard Ginori there is an appreciation for the hand made.

The iconic Richard Ginori flagship—which first opened in 1802 in the prestigious Palazzo Ginori on Via de’ Rondinelli in Florence—celebrated a reopening as well recently. Organized in various rooms to evoke a charming country villa, the 5,000-square-foot shop features both coffered ceilings and vaulted ones painted with Richard Ginori’s Galli Rossi pattern in blue, a rooster motif used in the brand’s tableware collections as well as its hand-painted wall tiles. Farm tables, weathered wooden cases, and vintage chicken coops are paired with 18th-century flora and fauna prints and porcelain chandeliers.

Ginori has gone back to market with a curated distribution channel. Only two boutiques worldwide: Florence and Milan, as well as a shop-in-shop that opened at Harrods in London last year. In Canada, Toronto’s Hopson Grace, the design-forward boutique devoted to the fine art of the table, is dedicated to showcasing Richard Ginori tableware.

Nearly 280 of the 300 workers who were laid off in 2013 have returned to work for Richard Ginori. The factory is once again fully operational, with artisans at their benches painting, glazing, decalling, and embellishing. It is inspiring to watch the skillful hands of the craftspeople as they work, continuing Richard Ginori’s centuries-long tradition of excellence.