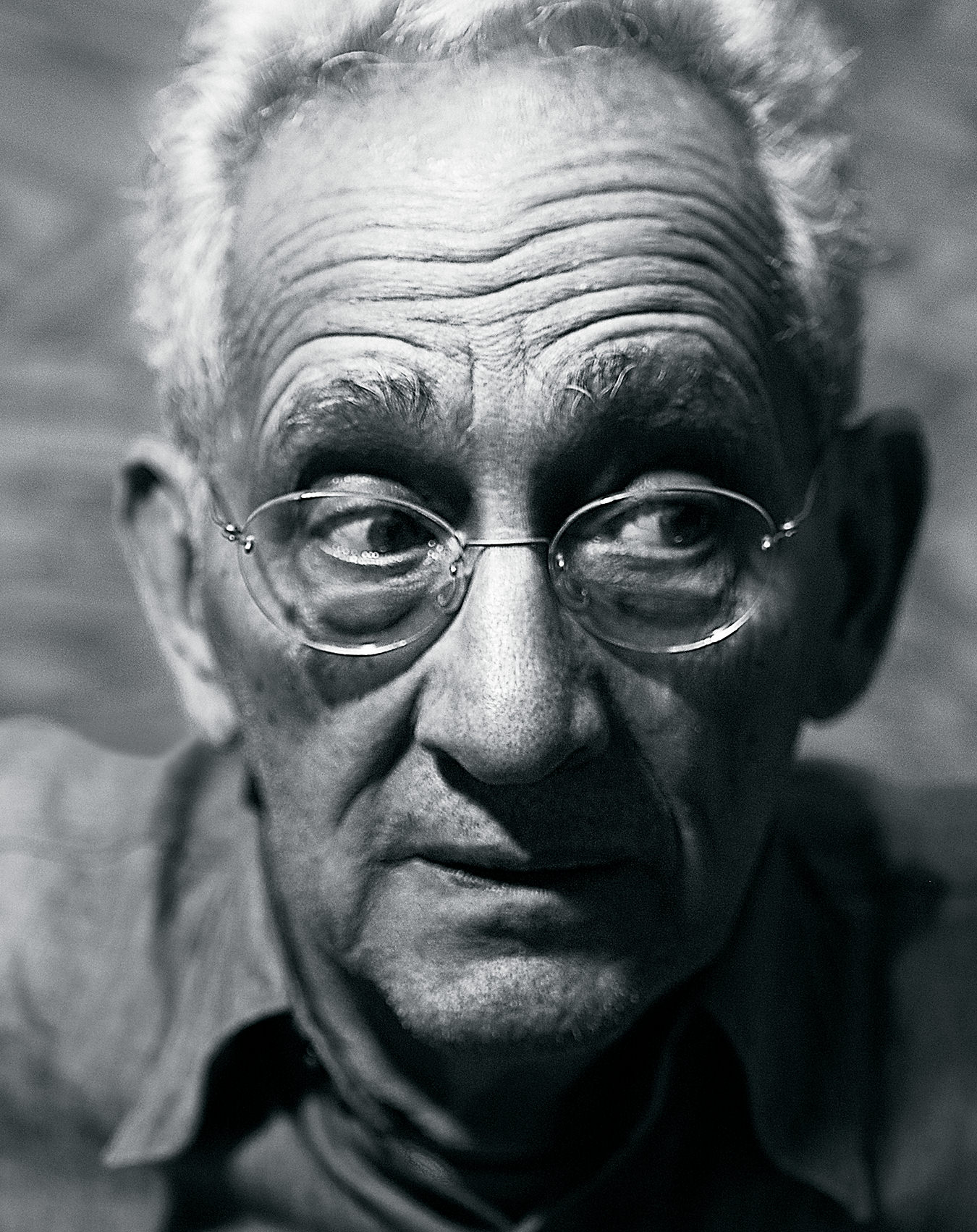

Frank Stella

Legend in the art world.

Frank Stella has been an icon of American art for over half a century. And at 72, the artist is active, articulate and all too relevant. In the 1960s, his work was at the centre of discussions about abstract art. Then, instead of repeating himself, he moved on and experimented, first setting his paintings free with shaped canvases, and then freeing them from the wall altogether with his sculptures and three-dimensional works. A leading abstract artist for half a century, he has been honoured with two retrospectives (the first when he was just 33) at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and he’s had work featured in major museums around the world. He has created block-long computer-generated murals, monumental sculptures and eccentric architectural models.

He could easily sit back and enjoy his recognition as one of the most important artists alive, yet he resists the label. Wiry and restless, with unruly grey hair and a deadpan delivery that evokes Woody Allen, Stella is modest about his career. “It’s not that special. You just fit into the world,” he says. “The determining factor is if you’re an active participant. I’m a guy who keeps making art.”

His remarks belie the fact that Stella’s work has had an immense impact on American art. “It sounds dramatic or interesting to other people, but I spend my time worrying about the work and about just keeping going. Making the pieces and trying to get things right is the main occupation.”

It has been his main occupation ever since he graduated from Princeton, moved to New York and rented a cheap studio in the l950s. He burst onto the art scene in his early 20s; his famous series, the Black Paintings (1958−1960), soon came to represent a new aesthetic in American painting, namely the transition from Jackson Pollock’s emotional abstract expressionism to the cool, symmetrical, pared-down style that came to be known as minimalism.

The Black Paintings are large canvases painted in symmetrical bands of black paint, separated by thin pinstripes of unpainted canvas, and their restrained, calculated aesthetic seemed a shocking reaction to Pollock’s wildly expressive use of colours and shapes. Soon, Stella’s phrase “What you see is what you see” became a manifesto for art that relates to nothing but itself, and keeps the viewer at a distance.

Jill, from Black Series II (detail). Photo courtesy of ©Albright-Knox Art Gallery/CORBIS.

It was an epochal moment, and art critics still refer to the Black Paintings today, as they did half a century ago when Stella had the New York art world buzzing. But just as he found himself enshrined as a minimalist, he left it all behind to blaze new trails in several different directions. He was an early optical artist, a pioneer of the shaped canvas, and ahead of his time in using enlarged prints. He was open to whatever medium came his way, including digital technology, and he anticipated the trend toward mixed media by using painting, relief, metal sculpture and digital printing—sometimes all within the same piece.

Stella burst onto the art scene in his early 20s, and his famous black paintings soon came to represent a new aesthetic in American painting.

His gargantuan body of work almost seems like the product of a dozen different creators, save two things: the inexorable progression of his paintings moving out from the wall, and an ever-increasing sense of the baroque, with its drama, curves and operatic extravagance.

Still, Stella has always kept his focus on pushing the limits of visual space rather than trying to be fashionable or competing with other artists. He says even in his early days, he never tried to trump the work of older stars like Jasper Johns and Jackson Pollock. “All that I hoped to be was like Jasper or Pollock,” he says. “Pollock was the whole thing, the whole idea.” He disputes the conventional wisdom in art-history texts that his Black Paintings were something new. “Probably my painting was a little different, not so gestural as Kline and de Kooning, say. But it was not so different from Rothko, Barnett Newman or Robert Motherwell. So it’s a bit of an exaggeration to say that my painting was against anything. It certainly wasn’t against abstract expressionism.”

After the Black Paintings, Stella produced a series of paintings that were based on bands of colour. In the Protractor series, begun in l967 and completed in l971, Stella incorporated enlarged semicircles and curves in bright colours. These were the first paintings that people wanted to buy; although the Black Paintings had been a critical sensation, at the time they didn’t sell like the work of more established stars like Johns and Pollock. Stella recalls that he was still living on the $75 a week he got as an advance from legendary gallery owner Leo Castelli. With the Protractor series, the young artist was able to wipe out his debt. “I started in l959. After eight years, I didn’t owe Leo anything. That’s eight years of success at zero value,” he says, grinning.

The early l970s marked the first of many changes in the way Stella used space. He started with his Polish Village series, reliefs in wood and paper that were inspired by photos of Polish synagogues destroyed by the Nazis. A few years later came the Exotic Birds series, razzle-dazzle abstractions inspired by the titular creatures: they were painted on aluminum and metal tubing, in sulphur yellow, orange, sharp blues and gashes of red, even glitter. “He has at last discovered his own sensuality as a painter,” said art critic Robert Hughes of the series in Time magazine in 1978, adding that the work was “the bravest performance abstract art has offered in years: manic energy channelled by an infrangible toughness of mind.” This new direction became known in the art world as Stella’s second career.

Oblivious to art trends and fads, and no longer the trail-blazing prodigy, Stella kept adding to his abstract reper-toire, using forms like cones, pillars and waves. In 1987, Hughes wrote, “Stella’s fearless panache and the profusion of his output refute the common idea that the possibilities of abstract painting are played out.”

Frank Stella in his studio, 1985. Photo courtesy of ©Nathan Benn/CORBIS.

Not everyone agreed. By the late 1980s, some in the art world regarded Stella as a “safe” artist, one whose work is used as adornment for various corporate headquarters. Yet he was just doing what he had always done—making art according to the dictates of his heart and mind. During the 1980s, he worked on a deliriously luminous series of reliefs and sculptures inspired by the novel Moby Dick. Stella was as obsessed as the novel’s whale-chasing Captain Ahab; when he told his son he was thinking of doing an image for each of the book’s 135 chapters, he recalls, his son reassured him that he didn’t have to do them all. “That so enraged me that I did more than one image for each chapter,” says Stella. “It’s a whole book.”

“It’s not that special. You just fit into the world,” he says of his career. “The determining factor is if you’re an active participant. I’m a guy who keeps making art.”

One of the works from the series, Pequod Meets the Rosebud, currently hangs high above the entrance to the Adelaide Club, an upscale health club in Toronto’s financial district. Its owner, Clive Caldwell, is a former squash pro who met Stella in New York in the early l980s. Recently, Laceland, which Stella did for the Cambridge Club (also owned by Caldwell), was moved to the gym. It’s a delightfully incongruous sight: a major artwork mounted high up on the wall of a gym, there for people to contemplate as they cycle or use the StairMaster to climb endless imaginary hills.

Another ambitious project with a Canadian connection began in the early 1990s. Stella was hired to create art for the Princess of Wales Theatre in Toronto by owner David Mirvish, an early and important collector of Stella’s work. Stella ended up creating designs for 10,000 square feet of murals, covering the inside dome, the walls and the stairways. He even designed the bas-reliefs at the end of each row of seats.

Stella began work on the theatre in 1992. “Once something worked, David would say, ‘Keep going.’ I don’t know how we did it, but we did it. Nobody made any money on the project, but it was fun,” he recalls. “I have never had a client like him. They all want a fixed budget and they can’t imagine more than one thing at a time—or in their lifetime.”

Mirvish made the decision to go with Stella “because I knew that he would not fail to surprise me. Many people who turn to an artist for a commission do so in the hope that the artist will repeat an earlier successful theme. But Frank Stella saw this as an opportunity to work in a new manner and to solve new visual problems, and ultimately to engage the audience.”

Throughout the 1990s, Stella’s work became three-dimensional, and he used found objects from junkyards and various metals, including stainless steel and bronze. The result was huge shapes—loopy, tangled, flying-saucer-like, and by no means universally praised. “A calculated monument to mess” was how a Washington Post critic described his 40-foot sculpture of aluminum, fibreglass and carbon fibre swirls, installed in 2001 outside the East Building of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

The prolific artist has never stopped working. But in the fickle New York art world, he was below the radar. Then in 2002, he had his first large show in Chelsea, the epicentre of the New York art scene. The show included sculpture, but the highlight was five l7-by-l4-foot canvases that seemed to contain all the techniques and forms Stella had ever used, including computer-generated grids, garish spray paint, stencils and spirals, partly printed and partly painted by hand. The New York Times commented on the “fascinating tactility” of Stella’s works, and concluded that he had become a better artist with each series: “What keeps you looking even when he’s not at his best is the clarity—some would say the obviousness—of his moves and his ideas about painting.”

Stella doesn’t see much evidence of good painting today. “A lot of it is porn or photoshop,” he says, explaining that there has been little great painting since Mark Rothko. “You don’t see that level of intensity, of clarity.”

Painting is, of course, Stella’s spiritual home. He notes that there should be good painting out there in the world, but he doesn’t see much evidence of it today. “A lot of it is porn or Photoshop,” he says, explaining that there has been little great painting since Mark Rothko. “You don’t see that level of intensity, of clarity.”

In the last five years, Stella has gotten more daring, and his work more complicated. Indeed, the older he gets, the more libidinally explosive the work appears to become. Yet at the same time, there’s a sense of cerebral control—critics have called him a high-IQ artist. But after so many decades, why continue to make such large, heavy, complex sculptures?

“With sculpture, you can get people to help you—to weld, for instance,” he says with a typical dismissal of his own accomplishments. Painting, he explains, is more difficult. “It’s not only the standing—you tense up, you’re there but always extending yourself, balancing on your toes. You’re making yourself tired.”

Stella doesn’t care much about categories, and at first his sculptures can seem puzzling. Artforum described one work in the Chelsea show as “a suspended agglomeration of what looks like aluminum ducting—either it’s sculpture or it’s the latest in ventilation”. The New Yorker called the show “frankly awful”, and described it as a “toneless visual cacophony”. (It’s worth noting that the following year, in 2003, Stella’s show of aluminum sculpture at the Paul Kasmin Gallery drew extravagant praise from that magazine: “Stella’s exclamatory energy soars in spiralling 3-D scribbles, composed of slender tubing and long tapering trusses.”)

The critics continue their uneasy relationship with his work, and his two shows at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2007 had some scratching their heads. There were pieces like adjoeman, a 17-foot-tall, 3,100-pound sculpture made of looping stainless steel and carbon fibre.

The New York Times opined that, upon Stella’s move to free-standing sculpture, “His efforts tend to become conventional, frivolous and emotionally hollow.” Other critics wondered how his eccentric architectural models could ever be inhabited in real life. Still, Stella was ahead of his time in criticizing stacked-box architecture, what he calls “identical panes of glass, one floor on top of another—the tyranny of squarefootage”. In the l990s, he wrote an article calling for an architecture that is less vertical and more horizontal, “closer to the reality of the landscape than the more arbitrarily geometrical”. His own architectural models for pavilions, chapels and museums are fanciful, with huge accessible spaces, improbable designs. As he has said, he’s an architect without a commission.

What will he do next? After transforming American abstract art with his Black Paintings; breaking the minimalist mould with his shaped canvases, painted reliefs, prints, sculptures and architectural models; and hitting the high notes of baroque exuberance, what is there left to do? Sitting back and enjoying his success seems out of the question. His output might be prodigious, but Stella gives the impression that he can’t wait to get back to work. Frank Stella, at age 72, is in the middle of his career.