-

The Aga Khan Museum collection contains some of the greatest artistic achievements of Islamic civilizations. Photo by Gary Otte, ©The Aga Khan Museum.

-

The Aga Khan Museum, designed by Fumihiko Maki. Photo by Gary Otte, ©The Aga Khan Museum.

-

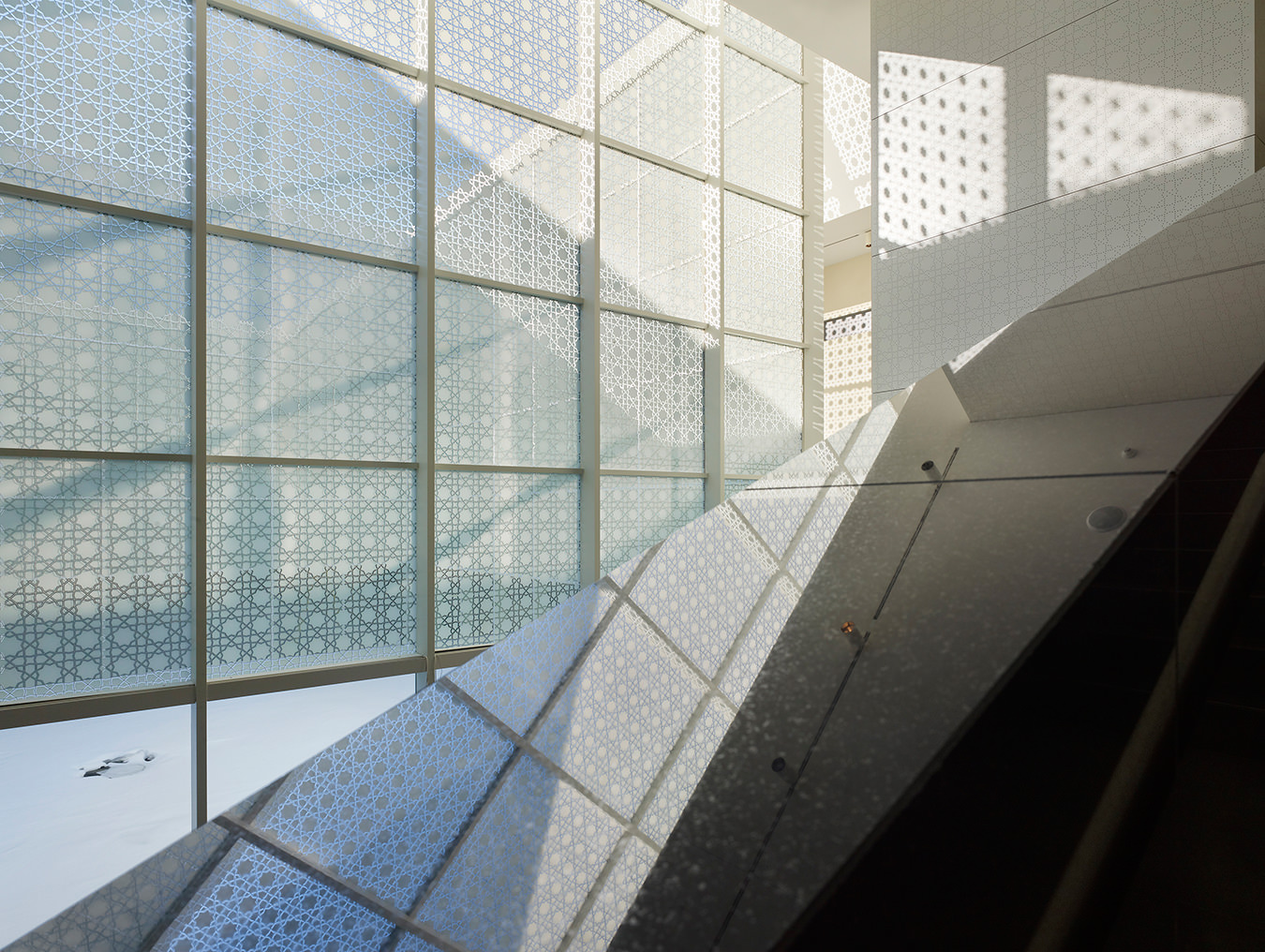

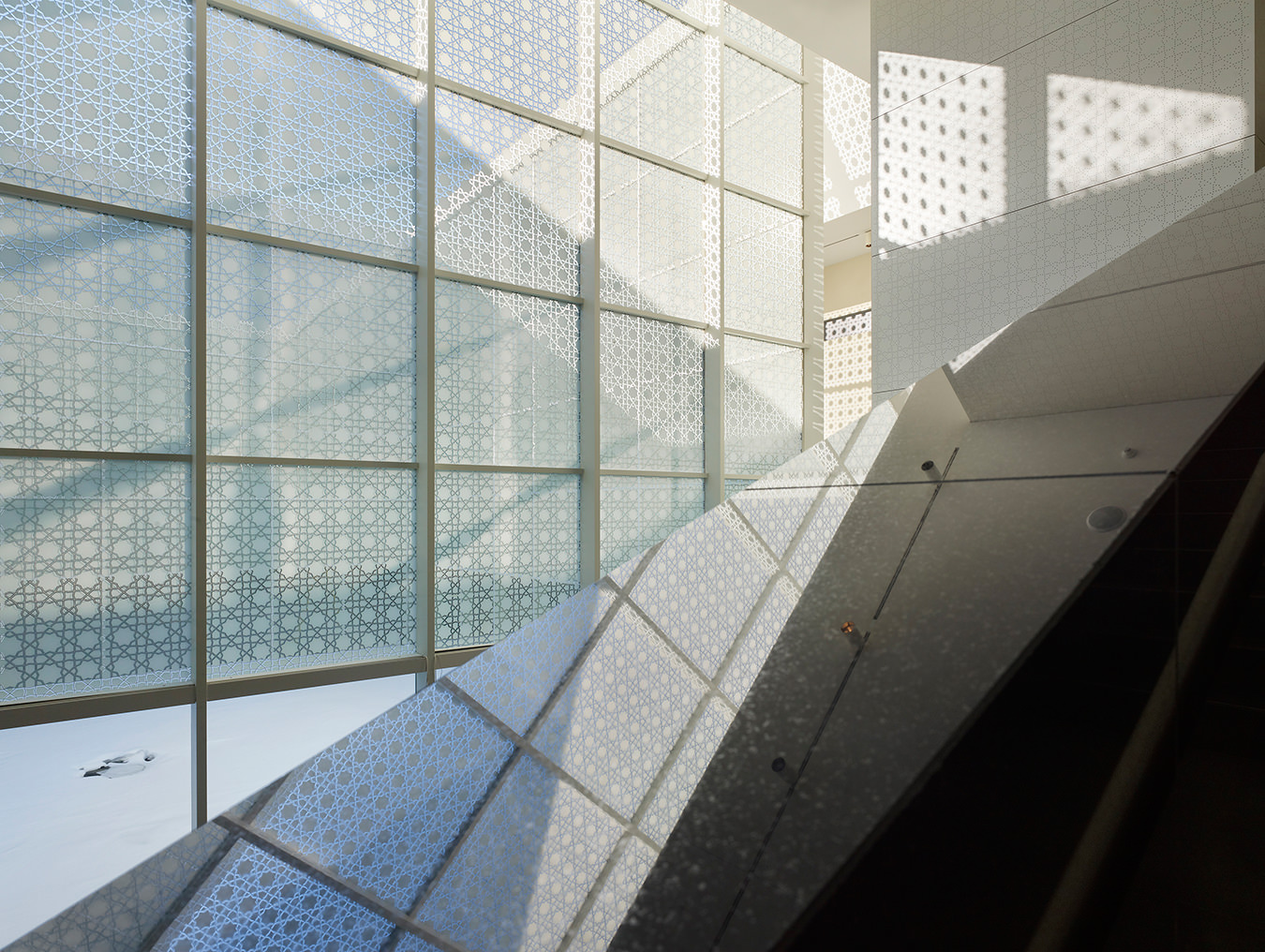

Mashrabiya patterns are etched in the glass that looks toward the courtyard. Photo by Gary Otte, ©The Aga Khan Museum.

-

The museum’s entrance. Photo by Gary Otte, ©The Aga Khan Museum.

-

The formal garden (inspired by a traditional chahar bagh) was designed by landscape architect Vladimir Djurovic. Photo by Tom Arban, ©The Aga Khan Museum.

-

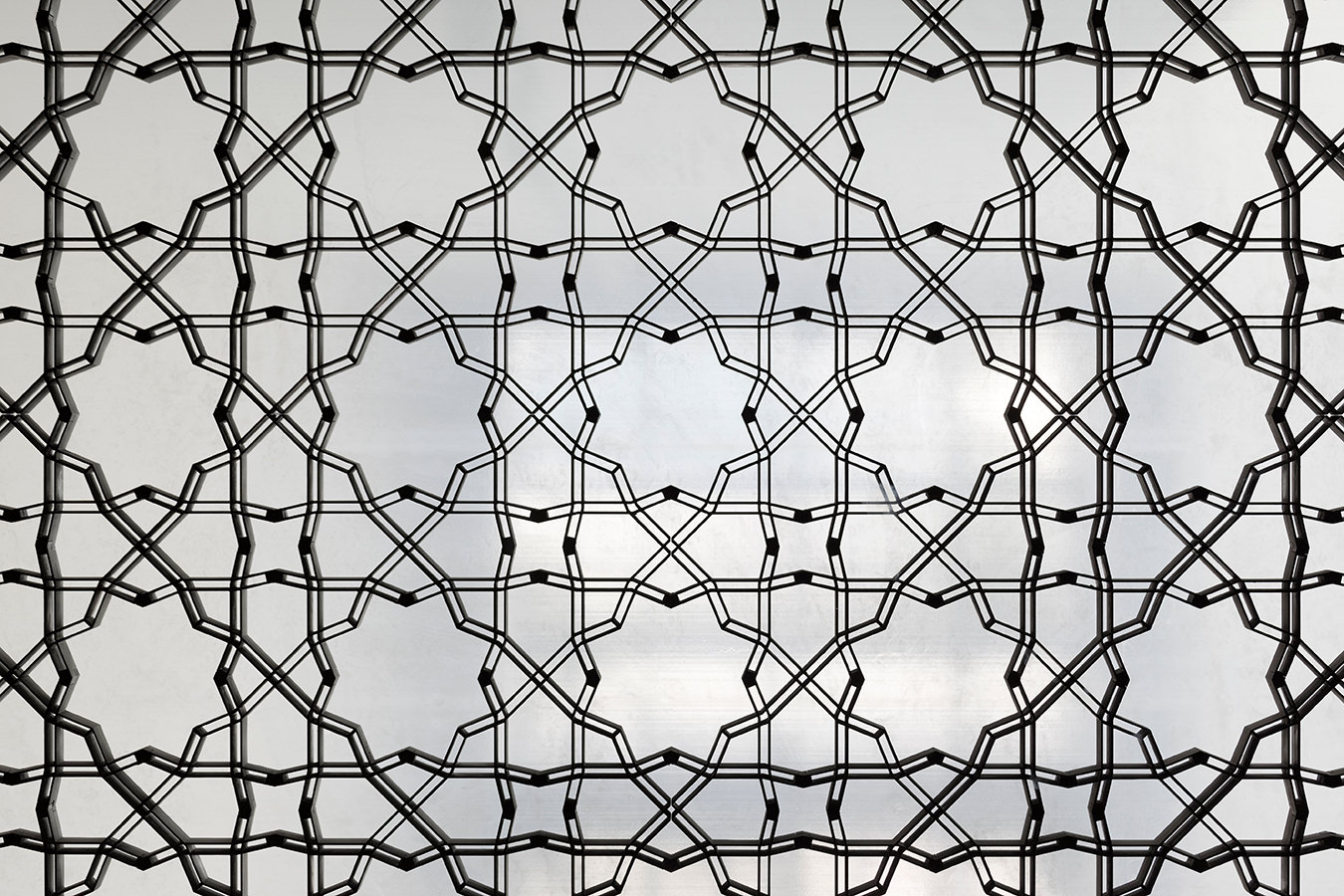

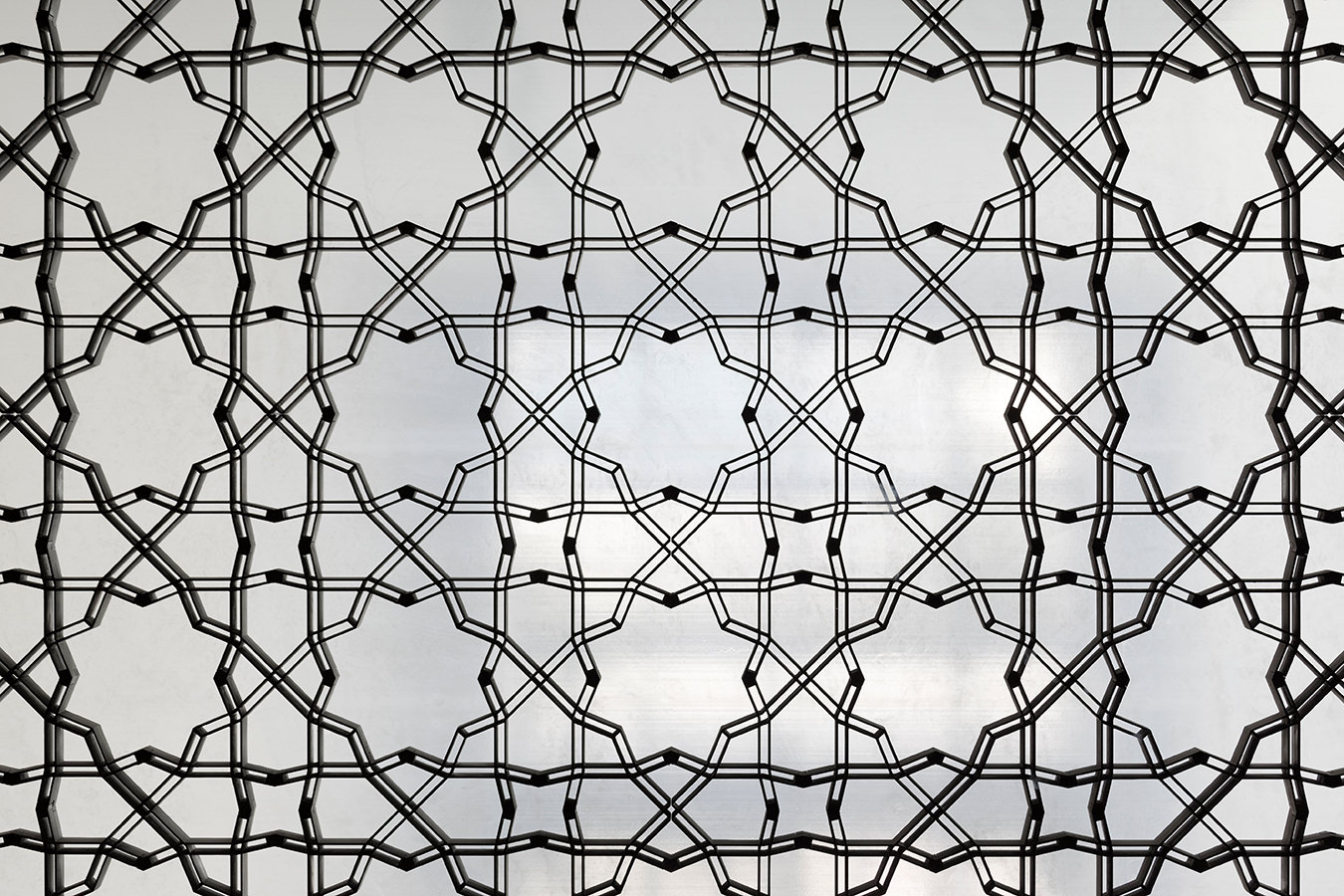

Mashrabiya patterns, like this one made from metal, are found throughout the museum. Photo by Tom Arban, ©The Aga Khan Museum.

-

The floor of the museum’s courtyard is made of limestone, lapis, and the same white Brazilian granite found on the building’s exterior. Photo by Tom Arban, ©The Aga Khan Museum.

-

The glass walls of the courtyard create patterned light and shadow throughout the museum’s atrium. Photo by Tom Arban, ©The Aga Khan Museum.

-

Ivory Horn (Oliphant), Southern Italy, 11th–12th centuries. Photo ©The Aga Khan Museum.

-

Ablution Basin, Jingdezhen, China, 1506–21. Photo ©The Aga Khan Museum.

-

Dish, Iznik, Turkey, 1570–80. Photo ©The Aga Khan Museum.

-

Capital, Spain (Historic al-Andalus), 10th century. Photo ©The Aga Khan Museum.

-

Planispheric Astrolabe, Spain (Historic al-Andalus), 14th century. Photo ©The Aga Khan Museum.

-

Displays in the Museum Collections Gallery. Photo by Gary Otte, ©The Aga Khan Museum.

-

An aerial photograph of the Aga Khan Museum. Photo by Kalloon Photography, ©The Aga Khan Museum.

Aga Khan Museum

A gleaming crown.

The Aga Khan Museum, designed by Fumihiko Maki. Photo by Gary Otte, ©The Aga Khan Museum.

In 21st-century Toronto, it’s not just what you build that matters, but where you build it. So when the new Ismaili Centre and Aga Khan Museum opened in September, locals were as surprised by the location of the project as by the project itself. The magnificent complex, what would be an architectural and cultural jewel in any city’s crown, sits atop a high point of land in the relentlessly depressing suburban landscape of northeast Toronto. It not only stands out from the dreary anonymity of condo towers, industrial parks, shopping malls, subdivisions, and highways, it puts them all to shame.

You don’t have to get out of your car to appreciate the full extent of what has happened. However fleeting, the view from Toronto’s busiest north-south highway, the nearby Don Valley Parkway, should be enough to convince even the most casual observer that something new and different and exciting is unfolding here.

The Aga Khan Museum collection contains some of the greatest artistic achievements of Islamic civilizations. Photo by Gary Otte, ©The Aga Khan Museum.

In addition to buildings by two of the world’s most acclaimed architects—the godfather of Indian Modernism, Charles Correa, and Pritzker Prize–winning Japanese practitioner Fumihiko Maki—the complex includes one of the world’s finest collections of Islamic art. In fact, the Aga Khan Museum is the first such institution in North America devoted to Islamic cultural artifacts. Its holdings range from centuries-old astrolabes and textiles to illuminated manuscripts and ancient ceramics, all of the finest quality.

If that weren’t enough, there is the exquisite set of gardens designed by Beirut-based landscape architect Vladimir Djurovic. Planted with more than 500 trees—mature trees—and more than 1,000 shrubs, these remarkable spaces stand in stark contrast to a city where everyone seems in too much a hurry to pay attention. This is a place of quiet contemplation and beauty that also knits the complex into a unified whole. The highlight is an arrangement of five reflecting pools, each lined in black granite and seemingly perfect, like some fully realized Platonic ideal. Though the gardens have just been planted, they are already a presence; the rows of cedars and other trees beckon from the highway.

Mashrabiya patterns are etched in the glass that looks toward the courtyard. Photo by Gary Otte, ©The Aga Khan Museum.

The heart of the complex is the Ismaili Centre, which serves as a gathering place, sacred and social, for the 30,000 Ismailis who live in the Toronto region. When first designed by Correa in the late 1990s and early 2000s, it was expected to be the only building on site; but when a contiguous parcel of land came available in 2002, the museum was added. Though they are clearly separate entities, the two parts are connected by a formal garden.

Correa’s contribution is a striking circular structure above which a large glass dome rises asymmetrically nearly 20 metres high. Unsurprisingly, it has quickly become a local landmark. In its own way, it has already put the neighbourhood and the street, otherwise banal Wynford Drive, on Toronto’s cultural map. The dome, which soars above the massive Prayer Hall, the spiritual hub of the compound, enhances the sense of spaciousness within and connection to the world without.

“I didn’t start by trying to find the identity of the centre,” Correa explains, “but by finding the axis mundi”—the place where heaven and earth meet—“and understanding the symbolism of the way the light comes into the room.”

On a more temporal plane, Correa’s task was to design something that would capture people’s attention, even when they’re speeding past on their way to or from somewhere else. “It’s a very formless part of the city,” the architect admits, “like the bottom of the sea or something. ‘HH’ ”—as His Highness is called when he’s not in the room—“was very keen that the buildings be seen. It’s a come-on.”

The galleries are simple and unadorned, the walls painted white. They are designed to enhance, not compete, with the artifacts on display.

His Highness, of course, is Prince Shah Karim Al Hussaini Aga Khan, the forty-ninth imam of Nizari Ismailis, who believe him to be directly descended from the prophet Muhammad. Known for his vast wealth, his racehorses, and a series of adultery-related divorces, the Aga Khan also presides over a network of enlightened philanthropic enterprises dedicated to the eradication of global poverty and the advancement of secular pluralism, women’s rights, and Islamic culture.

Toronto was chosen as the location of the Aga Khan Museum after plans to build it on property near the House of Commons in London, England, fell through. Though the decision meant that Correa had to realign and redesign the Ismaili Centre, the move was a huge coup for Ontario’s capital. Impressed by Toronto’s hyperdiversity and its tradition of acceptance, the Aga Khan decided to locate the museum and its priceless collection at the 6.8-hectare site in the early 2000s.

The museum’s entrance. Photo by Gary Otte, ©The Aga Khan Museum.

The formal garden (inspired by a traditional chahar bagh) was designed by landscape architect Vladimir Djurovic. Photo by Tom Arban, ©The Aga Khan Museum.

The billionaire spiritual leader spared no expense. The official budget was $300-million, but no one would be surprised to discover it cost more. Not only are the materials the finest, the designers of the Ismaili Centre opted to excavate an underground garage to keep the grounds as free as possible from the ever-present parked car. Though it would be an overstatement to call the subterranean facility attractive, it certainly has more going for it than the average parking pit.

The most obvious example of a preoccupation with detail is the passageway that leads from the parking area to the museum; it has been transformed into a walk through a magical slide-show consisting of high-definition images of artworks on view in the gallery ahead. In this darkened space, the figures—many taken from the collection’s superb 17th-century Persian miniatures—come alive in unexpected ways. Created by Parisian exhibit designer Adrien Gardère, who also handled the museum displays, it is a brief but intense mood-setter. Eschewing the usual strategy of filling darkened galleries with objects under a spotlight, he opted instead for something much less precious.

Mashrabiya patterns, like this one made from metal, are found throughout the museum. Photo by Tom Arban, ©The Aga Khan Museum.

“We didn’t want to take the usual ‘jewellery box’ approach,” Gardère says. “We didn’t want to put priceless objects by themselves in the dark. We also wanted to avoid the overcrowded feeling you find in many galleries. Here there is light and space.”

There’s no doubt about that. With its white Brazilian granite cladding and canted roof, the museum takes on an almost fortress-like appearance. Doors and windows are set back, which seems to emphasize the monumentality of the structure. Unlike the Ismaili Centre, which exerts a welcoming presence, the museum feels restrained, almost aloof and inwardly focused, as if its most important job were to protect the treasures within. Indeed, it might be a treasure chest, open at the top.

Contrary to expectations, the interior of the museum is airy and filled with light that enters the building through a small open-roofed courtyard. The galleries are simple and unadorned, the walls painted white. They are designed to enhance, not compete, with the artifacts on display. Maki’s minimalist sensibility serves the exhibits well.

Assembled by the Aga Khan’s late uncle, Prince Sadruddin, the 1,000-piece permanent collection is not large by museum standards. It can’t match the huge holdings of institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum in New York and the Victoria and Albert in London. But what it lacks in size, it makes up in quality, boasting scientific equipment and philosophical treatises as well as carpets, ceramic bowls, and decorated pots. Much of the collection is devoted to items that served some practical purpose. The intention is to illustrate the breadth of Islamic artistry and the many ways it appears on even the most humble objects. A good example is an Iranian beggar’s bowl from the late 16th century. With its extraordinary engraved surfaces, it would have made even its poorest owner feel rich.

The glass walls of the courtyard create patterned light and shadow throughout the museum’s atrium. Photo by Tom Arban, ©The Aga Khan Museum.

“The Aga Khan Museum has an international outlook,” says its director and CEO, Henry Kim. “Home to a collection of astonishingly beautiful works of art, it will showcase the artistic creativity and achievements of Muslim civilizations from Spain to China. I think local and international visitors will be greatly surprised when they discover just how much the arts of Muslim civilizations are a part of our shared global cultural heritage.”

From the beginning, the Aga Khan, a serious architectural patron, was intimately involved in every detail of the project. In addition to being bankrolled by his international development fund, the museum clearly has great personal significance to him.

It is, after all, a realization of principles to which his branch of Islam clings despite its long and sometimes difficult history. The first wave of Ismailis arrived in Canada in the 1970s; many came from Uganda where the dictator of the day, Idi Amin, had launched a program of persecution against the community. Due to their strong tradition of engagement and tithing, Ismailis prospered in this country. And as they have spread across the globe, they have made a point of adapting to local conditions.

Architecturally, this means the Toronto buildings are not copies of forms and styles that evolved elsewhere. Unlike some of the religious structures constructed in this city—Hindu temples, for example—which are faithful reproductions of ancient originals that evolved in other parts of the world, the Ismaili Centre and Aga Khan Museum are contemporary buildings in every sense.

Both Correa and Maki have worked for the Aga Khan before, and both were hand-picked by him for the Toronto commissions. This sort of top-down approach is rare in an age of building committees and design review panels, but it ensures a level of consistency that can otherwise be hard to obtain. In the case of the Aga Khan, it also means a commitment to excellence that is hard to find at a time when the costs of construction are so high. To put this in a suburban context is even more unusual. In Toronto, where the suburbs are not known as cultural hotbeds and land is disposable, the implications of a project such as this are radical. No, the “burbs” won’t change overnight, but perceptions will. Until recently, the idea that buildings as distinguished as these would appear in distant Don Mills would have seemed impossible.

Planispheric Astrolabe, Spain (Historic al-Andalus), 14th century. Photo ©The Aga Khan Museum.

It’s true the Ontario Science Centre is not far from the Ismaili Museum; but it’s a different sort of place. With its utilitarian aesthetic, the OSC looks as if it could be a subway station or some public facility—maybe a water purification plant—where the main concern is the durability, and in this case, the wear and tear of kids and crowds. The Science Centre was designed to withstand its purpose; the Ismaili complex was intended to enhance it. The attention to detail puts the focus on the individual visitor, not the passing hordes. The Aga Khan Museum would be an object of beauty regardless of location, but not, perhaps, an invitation to rethink the context.

That’s why the Ismaili complex is a challenge as well as a gift. It represents an act of faith as much as an invitation to change. It also suggests there is value where others have seen little or none. The effects have yet to be played out fully, but they will be transformative. Not only will Canadians enjoy unprecedented access to Islamic history and culture, many will be thrilled that suburbia has turned a corner. In raising the stakes so high, the centre has set an example that can’t be ignored. It’s here for good.