A Rare Vintage

Anthony von Mandl’s vision and aesthetic tastes have assured the Okanagan Valley a charmed future.

Anthony von Mandl, proprietor of VMF Estates, in the von Mandl Dining Room at Mission Hill Family Estate.

At the base of Mission Hill Family Estate’s monumental bell tower is a cast-iron sculpture affixed to a rectangular block of granite. The humanoid statue, angled forward at 10 degrees, is imposing, solitary. Its stance is reminiscent of a ski jumper reaching takeoff: arms alongside the unwavering, board-straight body, a concentrated gaze outward and upward. The sculpture—Encounter by Icelandic artist Steinunn Thórarinsdóttir—is emblematic of the winery’s proprietor. Whether it’s ski jumping or empire building, with Anthony von Mandl, it’s all about how far you can fly.

From its landmark hilltop perch in British Columbia’s Okanagan Valley, Mission Hill Family Estate has come to represent the finest of winemaking—not only within Canada, but globally, as is evident in its international acclaim. It has its beginnings back in 1981, when von Mandl purchased Golden Valley Winery—which at the time had only rundown sheds with dirt floors and a few barrels—and renamed it Mission Hill. (It’s a reference to the site’s original name when its first owner, Riley Paul “Tiny” Walrod, developed it in 1965.)

A lot of people with money get into the wine business, yet von Mandl, who began his career importing wine from an office in the back of Vancouver’s Queen Elizabeth Theatre, had little when he set out to build his dream. “I’d pulled together all the money I had, including my house, all the financing available,” he says. “And I was still about $200,000 short. I suggested we toss coins for $10,000 off the asking price per toss.” He won enough tosses to make up the difference.

Mission Hill Family Estate, from its landmark hilltop perch in British Columbia’s Okanagan Valley, represents the finest of winemaking.

The reputation of the Okanagan Valley (at the time known for its inferior non-vinifera varietals) and those nerve-wracking coin tosses together symbolized von Mandl’s gamble. But he believed in the Okanagan’s winemaking potential. “I knew from the fruit,” says the Vancouver native, “the taste of the apples, the apricots, and the peaches.”

Von Mandl’s career path reads like a wine review: complex and sophisticated, with nuances both elegant and earthy. There is an observed humility to the man, and yet his self-assurance and drive has allowed him to achieve what he admits was an audacious dream: to build one of the world’s 10 most recognized wineries in a region that nearly nobody had heard of. The wine magnate is a deeply private individual, but spend time with him and it becomes evident he was determined from his youth that he was going to be someone someday.

His father, Dr. Martin von Mandl, along with his mother, Bedriska, moved the children (von Mandl has a sister, Patricia) to Europe when he was nine. They lived in Vienna, Austria, and “my parents dedicated everything they had toward providing us with a vast education, which included attending schools in Switzerland and Germany,” he says of his childhood. “We were immersed in aspects of European history, art, and culture.” Of his time spent in Europe, von Mandl refers to the period as an influential “gift”—to be exposed to the wonders of the Old World.

The family returned to Canada, and in 1972, von Mandl graduated from the University of British Columbia with a degree in economics and apprenticed in the wine trade before founding the Mark Anthony Group that same year. Having proved himself resoundingly successful as a merchant, he turned his passion of importing wine into a business of making wine. After his initial investment to buy Mission Hill, he needed more capital to build his dream, but the banks had no plans to loan him anything more—interest rates in the 1980s had soared to 21 per cent. “I was pushed back into a corner,” says the imaginative entrepreneur. “I learned then that innovation comes from desperation.” So he turned to a side business. Golden Valley Winery had been producing cider; von Mandl added fruit-flavoured ciders to the range, renamed it Okanagan Premium Cider, and watched sales rise from 18,000 cases annually to several hundred thousand within a few years.

View from the 12-storey bell tower, at Mission Hill Family Estate, where four bronze bells handcrafted by Fonderie Paccard, in France, are housed.

That ingenuity proved successful again in 1986, when he brought Corona—at the time, an unknown Mexican beer—to Canada. The move amassed staggeringly high sales for Grupo Modelo, the brand’s producer. In fact, at the time, Canada was the fastest growing market for Corona in the world. But in 2007, Grupo Modelo abruptly pulled the rug out from under von Mandl by terminating his contract, after having formed a joint venture with a multinational conglomerate to market Corona in Canada. “You’ll come across all kinds of challenges,” he says now of the takeover. “Things that will surprise you in negative ways. The big thing is not to have your spirit broken.”

A year later, he decided to build Turning Point Brewery on Annacis Island in Delta, B.C. In a speech to the British Columbia Technology Industry Association in 2010, he called it an “insane investment”; in light of history, one could wonder if the play was fuelled by resentment over his experience with Corona. “We put $20-million into building a craft brewery we could have done for $1-million,” said von Mandl. He fitted the brewery with new stainless steel tanks and other sophisticated German beer-making technology, and even added an on-site wind turbine in a commitment to sustainability. Von Mandl does not talk specifics about revenues, but, he says, the company “is the Porsche of breweries, and today it handcrafts Belgian style beers that are some of the most difficult to produce.”

But von Mandl’s largest profit has been with a more ubiquitous product: Mike’s Hard Lemonade. With Mike’s, he created an entirely new alcohol beverage category: ready-to-drink (RTD) spirits, and after its introduction in 1996, sales across Canada soared. Whether von Mandl’s initiatives grew out of necessity or desire, there is no denying his wizardry.

It took another three years for von Mandl to get Mike’s into the United States: regulations stipulated that the alcohol source had to be malt based, not distilled. But a malt base has too much flavour, so von Mandl devised a patented process that produced flavour-free malt-based alcohol. Mike’s Hard Lemonade launched in the U.S., and today, the brand is up for sale, with Reuters reporting it at a value of $1-billion (U.S.).

Yet all of this—the cider, the beer, the Mike’s—was ultimately in pursuit of a vision that, according to von Mandl, “has always focused on fine wine”: Mission Hill Family Estate and its offerings. “There were plenty of growing pains,” says von Mandl in the deliberate, thoughtful way he speaks—but one gets the sense he didn’t have any fear of failing.

The Okanagan is the biggest of the B.C. wine regions, with 163 of the province’s 215 wineries and 88 per cent of its vineyard area. Located in a rain shadow of the Cascade and Coast mountain ranges to the west and the Monashee Mountains to the east, the Okanagan is a dry region, with only around 345 millimetres of rain a year in the wettest parts. It has a distinct climatic advantage, as the valley is 1.5 degrees warmer than Napa during the peak months of July and August.

The pinnacle of the Mission Hill Family Estate portfolio is Oculus, a Bordeaux-style blend.

Soon after purchasing Mission Hill in 1981, von Mandl gave a speech to the Kelowna Chamber of Commerce, in which he described his visionary hopes for the region: “When I look out over the valley, I see world-class vinifera vineyards winding their way down the valley, numerous estate wineries, each distinctively different, charming inns, and bed-and-breakfast cottages seducing tourists from around the world … In short, the dream is the Napa Valley of Canada, but much more.”

Today, true to that vision, wineries are strung in a series of clusters up and down the length of the 200-kilometre Okanagan Valley. Most are family-run operations that harvest grape varieties such as pinot noir alongside cabernet sauvignon, merlot, and cabernet franc; white varieties such as pinot gris, chardonnay, and riesling have long done well in the region. The lack of a single signature variety might be problematic in terms of marketing the region, but that just reflects the diversity of vineyard sites. For the 12 months ending November 2014, the B.C. wine industry’s annual VQA wine sales totalled $247-million, representing 1,162,729 nine-litre cases of wine.

Of all the wineries in the region, the architecturally impressive Mission Hill Family Estate, designed by Seattle-based Tom Kundig of Olson Kundig, is one of those magnificent buildings that anchors a city. A second glance at the postcard-perfect estate is when its fine beauty and logic overcomes its formidable quality, as the architect’s modernist sensibility gently asserts itself. And from the fields to the cellars, in all their meticulous precision, you’ll find von Mandl’s touch at every turn, hoping, as vintners have for centuries, that this year the balance of sun, soil, and rain will produce a vintage for the ages.

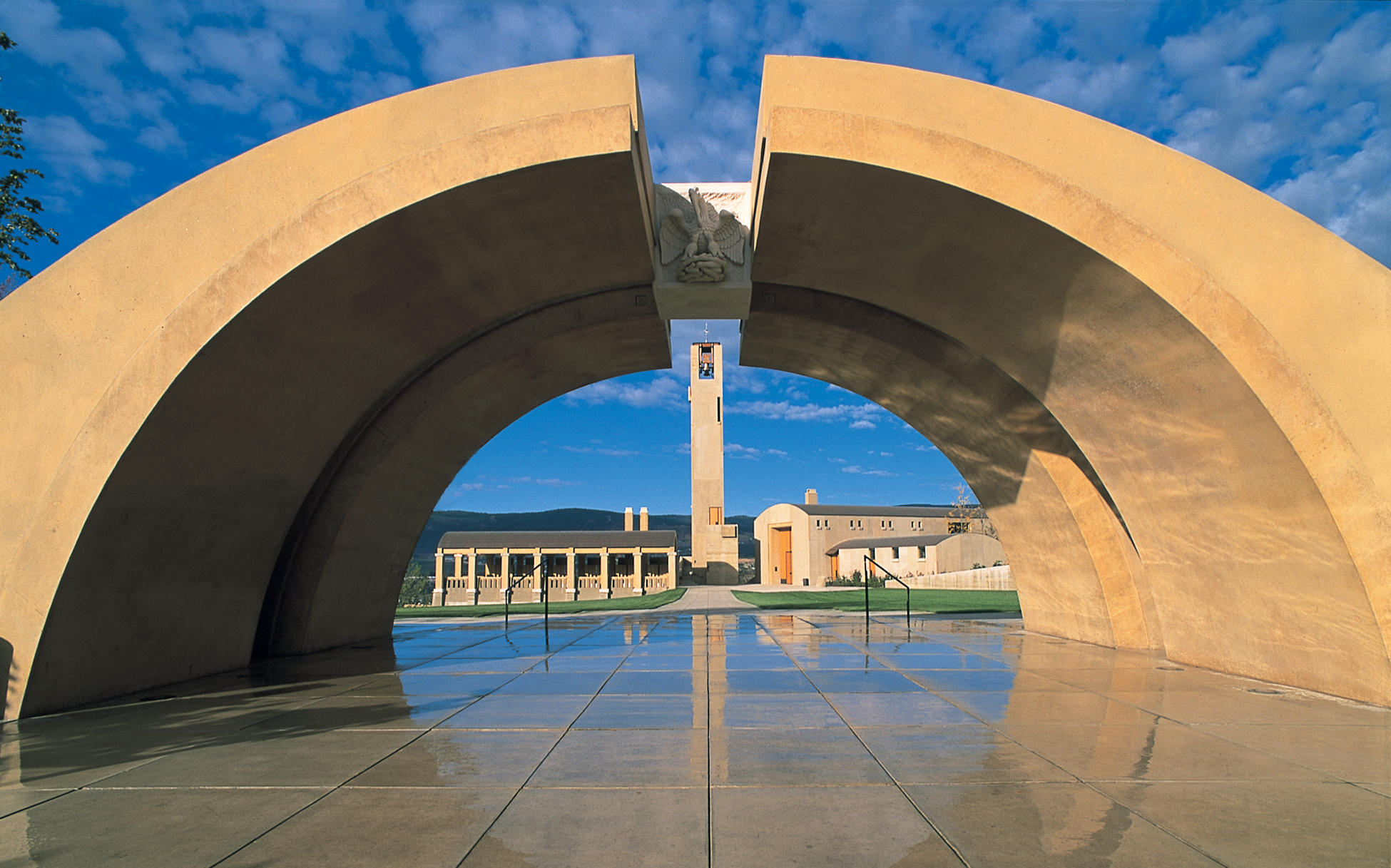

“We are rushing through life,” says von Mandl, “and the intention when visiting here is to have our thoughts turn inward.” The entry gates deliberately force cars to slow their speed when passing through; an allée bordered by oak trees helps transition the visitor from the hurried pace of daily life into the world of winemaking. As visitors pass under the curved arches that are held together by a single keystone chiselled by hand from a single block of Indiana limestone that carries the von Mandl family crest, the view gives way to the courtyard. Once inside, the eye is drawn to the imposing 12-storey bell tower, where four bronze bells handcrafted by Fonderie Paccard in France (the foundry that cast the bells for New York’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral and Sacré-Coeur Basilica in Paris) ring. The barrel-aging cellars have been blasted into exposed rock and supported by curved arches that span their width. The Estate Room houses a display of antique drinking vessels, including 17th-century English glass flagons recovered from a shipwreck and, spotlighted in the centre, a 2,400-year-old Greek amphora that dates back to the Ancient Olympics of the fourth century, BC.

At any given moment, von Mandl will point out some finely wrought detail and speak of its mechanism; each antiquity has a story, from the Marc Chagall tapestry to the Fernand Leger carpet to the 16-person table once owned by Henry Luce, the founder of Time magazine, in the private von Mandl Dining Room. “Coming here is coming to our family estate,” says von Mandl of Mission Hill, where he and his wife, Dr. Debra Gibson, a doctor of traditional Chinese medicine, along with their seven-year-old son, spend a good deal of their time. If wealth can buy one lasting pleasure, it is convenience, and von Mandl and his family commute by private jet between their homes in Vancouver and Kelowna.

There is an experience to the movement as one moves from place to place in Mission Hill—never hurried, and in a conscious state of serenity. At the Terrace Restaurant, which overlooks vines of pinot noir and chardonnay, executive winery chef Chris Stewart prepares seasonal fare to further complement the Mission Hill Family Estate wines. There’s even an open amphitheatre, where the likes of Tony Bennett and Chris Botti have performed. “We’ve only just begun inspiring others; I believe that fervently,” states von Mandl early in the day. And now, as he walks across the courtyard, a string of visitors approach him and thank him for what he has created. He is the ever-gracious host, welcomes each of them as he shakes their hands.

Dr. Martin, von Mandl’s father, never lived to see his son’s dream. He died of a heart condition in 1992, en route to the Four Seasons Vancouver for lunch with his wife, who is now 99 years old. “My father’s greatest lesson was to never make a decision when backed into a corner. There is always a way out,” says von Mandl. Prudent words from a man who made his profession practicing law. Strategic decision making, concentration, tactics, and evaluation have been von Mandl’s way out.

From the vineyards to the cellars, in all their meticulous precision, you’ll find Anthony von Mandl’s touch at every turn.

The wine business involves spreadsheets and science, but the basics still come, as they have for centuries, from the vines; and presiding over them is John Simes. In the midst of the 1992 harvest, von Mandl hired the New Zealander as winemaker after searching for two and a half years. Simes set the tone for excellence early on by winning the award for Best Chardonnay in the World, the prestigious Avery Trophy at London’s International Wine and Spirit Competition (IWSC) in 1994. The award gave everyone at Mission Hill an elevated confidence. “It proved we could play on the same stage,” says von Mandl. (Stature in the wine world for von Mandl is such that he is the only Canadian to have been honoured as president of the IWSC, where notable past presidents include Robert Mondavi, Baroness Philippine de Rothschild, Marchese Piero Antinori, and Dr. Anton Rupert.)

Today, Mission Hill has assembled distinct vineyard holdings, strategically located in diverse terroirs from Kelowna in the north to the U.S. border, which showcase the unique soils and microclimates of each region. International oenologist Michel Rolland consulted for Mission Hill for a time; vineyard maintenance under director of viticulture James Hopper has been ongoing and is now so methodical that it is almost a vine-by-vine program. Never shying from investing in winemaking equipment to help the team to get the most out of the grapes has been crucial. Thus, the vineyard operations are becoming increasingly high-tech: recent innovations include drones that create aerial maps and overviews to better see and understand vine stress and vigour. And yet von Mandl remains attentive to the timeless character of the wine world: “Wine has been the same for 10,000 years. There is technology that has aided the process, but the vines—all that hasn’t changed,” he says. This is no business for the impatient or for those who have a taste for the quick dollar. Ten years can pass from the time a new vine is planted until its wine comes to market. And nature always has the last word.

The barrel aging cellars at Mission Hill Family Estate have been blast into exposed rock and are supported by curved arches.

The pinnacle of the Mission Hill portfolio is Oculus, the Bordeaux-style blend that Simes first created in 1997. It crowns a large and impressive portfolio of wines, where ripeness, elegance, and complexity imbue Quatrain (merlot, syrah, cabernet sauvignon, cabernet franc) and Compendium (cabernet sauvignon, merlot, cabernet franc), while Perpetua signals a modern style of chardonnay. Made from the finest blocks and the finest lots, these reflect a connection to the land with a European style. From the 2009 vintage, a single-vineyard riesling, Martin’s Lane, was created, named in honour of von Mandl’s late father, and the portfolio has since been extended with a viognier and pinot noir, the latter winning the trophy for Best Pinot Noir in the World at the 2013 Decanter World Wine Awards in London—beating out more than 14,000 wines.

Early last year, von Mandl announced the acquisition of CedarCreek Estate Winery after acquiring Oliver-based Domaine Combret Estate Winery, already refurbished and rebranded as CheckMate Artisanal Winery, which produces small-lot Burgundian-style chardonnay. Von Mandl has re-engaged Kundig for his latest project: a purpose-built, gravity-fed, pinot noir–specific winery, also called Martin’s Lane that will crush for the first time this fall. As he walks, von Mandl is animated about the nearly completed construction, pointing out where a suspended stairwell in the entrance atrium will be realized, the 37 Lasi stainless steel tanks (“the Rolls-Royce of tanks,” he says), the six concrete fermenters produced by Nomblot, the inconspicuous illumination (von Mandl doesn’t like to see light sources). Seventeen thousand cubic metres of earth were removed for this new winery, and the glass and Corten steel–wrapped building has been dropped in the landscape in a manner that could accurately be described as caring. “We want to bring together the finest pinots in the world,” says von Mandl of his new invitation-only winery. And he is certainly confident about his new venture, saying: “We will open a bottle of pinot from Burgundy, Sonoma Country, Oregon, and compare it to ours here. The best versus the best.”

The never complacent von Mandl is far from being done. He’s transformed the wine business in Canada, and soon after acquiring CedarCreek, von Mandl created VMF Estates (von Mandl Family Estates) to encompass the family’s winery and vineyards in the Okanagan. Simes has transitioned from chief winemaker at Mission Hill to focus on the VMF Estate’s diverse collection of Okanagan vineyards. “The first and formative chapter of our region and Mission Hill has been written,” says von Mandl. “Now, we begin the second.” Outward and upward.

Martin’s Lane is an invitation-only, purpose-built, gravity-fed, pinot noir–specific winery that will crush for the first time this fall.