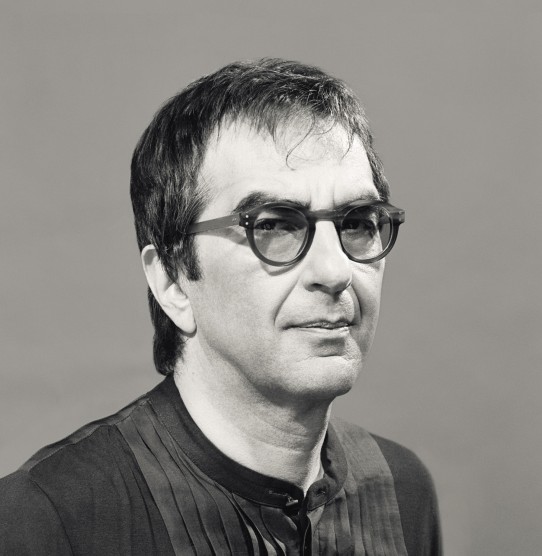

Atom Egoyan

A captive mind.

Atom Egoyan’s office, at the back of a drab Victorian semi in downtown Toronto, is a walk-in scrapbook. The walls are entirely papered with layers of memorabilia documenting the Canadian filmmaker’s life and career—photographs, letters, press clippings, and posters, tacked up with push-pins and curling at the corners. This dense archival quilt has grown considerably since I last visited the office 20 years ago. That’s when I first interviewed Egoyan for the release of Exotica, the movie about sex, death, and babysitting that launched his celebrity in Cannes and gave Canadian cinema instant notoriety.

Since then, in a career that spans 14 feature films, he has received five prizes at Cannes, two Academy Award nominations, 10 honorary degrees, an Order of Canada, and a French knighthood. He’s made Hollywood movies and experimental shorts, directed operas and plays, designed art installations, published books, and recently written his first stage play since his student days. And this May, he was back in competition at Cannes for the first time in six years with The Captive. The movie, which stars Ryan Reynolds as the father of an abducted girl, is Egoyan’s 14th feature, and it brings his career full circle; he co-wrote it with his oldest friend, David Fraser, who remembers meeting him on their first day of class at the University of Toronto’s Trinity College, in 1978. (“I walked into the quad,” Fraser recalls, “and there was this guy sitting barefoot, playing classical guitar. He told me he wrote plays.”)

Still trim and boyish at 53, Egoyan offers me a chair in the corner of his office beside a banjo propped against a wall, and seats himself on a file cabinet. He’s dressed entirely in black, from his boots and jeans to a thin sweater worn as a shirt. After interviewing him countless times, and giving his films more than one critical review, I joke that I’m overqualified. Perhaps he’d rather be freshly discovered by some sweet young thing.

“I’ve already made a movie about that,” he says with a laugh, referring to Where the Truth Lies (2005), his erotic intrigue about a young celebrity journalist, which ranks as his most expensive picture and biggest flop. And as if to remind me that he hasn’t forgotten my review, he adds, “I still don’t agree that Alison Lohman was miscast!” Egoyan is so personable, it’s hard not to like him (ask anyone), but as a film critic I never felt a need to coddle his work. It helps that he doesn’t hold grudges. In fact, he embraces critical discourse and re-examines his own work with a forensic scrutiny.

Guiding me through the archival maze of his office like a boy eager to show me his room, Egoyan quickly locates the Maclean’s feature I wrote about him in 1994. Nearby is a photo of him at Exotica’s Cannes premiere with his wife, actress Arsinée Khanjian, and their then-nine-month-old boy, Arshile. The director points out another shot of Arshile being hoisted in the air by cult filmmaker John Waters on a patio in Taormina, Sicily, noting that the man at the café table behind them is Michelangelo Antonioni, the legendary Italian auteur who changed the way we look at photographs with Blow-Up.

Egoyan brings a curator’s eye to the remembrance of things past. On his walls, no rite of passage is left undocumented. There’s a photo of Atom receiving his kindergarten diploma; Atom hanging with Quentin Tarantino; Atom accepting a prize in Cannes from John Travolta for The Sweet Hereafter; Atom’s name highlighted in a newspaper story about Ingmar Bergman, who cited Egoyan among his favourite young directors—this one is especially close to Egoyan’s heart considering that, as a 14-year-old playwright, he caught his first glimpse of cinema’s potential by stumbling across Bergman’s Persona on late-night TV.

Egoyan’s office would not be out of place in one of his own dark, enveloping dramas, where memory unfolds as a collage of artifacts, often via creepy rituals of surveillance. Or one of those serial-killer dens that might turn up in a thriller. Egoyan’s game is art, not murder, but it is riddled with voyeurs and predators, lost children and bereft parents. Take The Captive: featuring a detective duo played by Scott Speedman and Rosario Dawson, the film revolves around the abduction of a nine-year-old girl who resurfaces at the age of 18, working for the same pedophile ring that seized her as a child. This fictional intrigue follows hard on the release of Devil’s Knot, which starred Colin Firth and Reese Witherspoon in a drama based on the true story of the 1994 West Memphis trial of three teenagers accused of murdering three children in a satanic ritual. In other words, this is not a director who will be making a frothy rom-com anytime soon.

Egoyan has built a fascinating, complex body of work by circling the same unhallowed ground of violated youth, haunting loss, and forged identity. His films bear a signature as unique as that of the Coen brothers, Jim Jarmusch, David Cronenberg, or even Antonioni. When you’re in an Egoyan movie, you’re in a place unlike any other—Egoyan’s own private twilight zone of awkward intimacy. Yet despite the dark themes, the director finds a warmth and tenderness in his characters, these fragile souls suspended in a state of longing, as if each film offers them a kind of solace. And it keeps coming back to the mirage of the nuclear family.

When you’re in an Egoyan movie, you’re in a place unlike any other—his own private twilight zone of awkward intimacy. Egoyan’s game is art, not murder, but it is riddled with voyeurs and predators.

It’s been three decades since Egoyan launched his career at 23 with Next of Kin, the tale of a young imposter who insinuates himself into a Toronto family of Armenian immigrants by pretending to be the long-lost son they gave up for adoption. Ever since, the director’s work has zeroed in on issues of fractured identity. But then, his own pedigree is all over the map: born in Cairo of Armenian parents, who were both painters, he immigrated to Canada at age 2, grew up in Victoria, B.C., and found his vocation in Toronto. Inspired by Harold Pinter and Samuel Beckett, he wrote plays as a teenager and moved on to short films in university. As a young writer/director/producer, he became a self-made prototype of indie efficiency. He forged a new template for creating festival buzz for auteur films made on a spare budget of public funds, while he honed his craft directing for television. Leading a new wave of Canadian filmmakers such as Bruce McDonald, Patricia Rozema, and Don McKellar, Egoyan saw his career blossom in the late eighties. After building a cult audience with a string of existential dramas—Family Viewing, Speaking Parts, and The Adjuster—he made his breakthrough in 1994 with Exotica, a multilayered mystery starring Bruce Greenwood as a bereaved father who looks for solace in a strip club. It was the first Canadian feature chosen for competition at Cannes in a decade. As Roger Ebert declared at the time, Exotica announced “Egoyan’s arrival in the first rank of filmmakers.”

The director is the first to admit that his career might have peaked just three years later with the triumph of The Sweet Hereafter. Starring a teenage Sarah Polley as the paraplegic survivor of a school bus crash that kills 14 children in a small town, the film won three prizes at Cannes, seven Genies, and a pair of Oscar nominations for Egoyan’s writing and direction. Pinned on his office wall of fame is a 1996 critics’ poll that named The Sweet Hereafter the best-reviewed film of the year. “That’s a tough one to top,” he admits. “I still think it was a fluke. People misread what my intentions were.” He says they misunderstood the film’s ending, in which Polley’s character lies about the cause of the bus accident in order to sabotage a lawsuit that divides the town. He feels most viewers assumed that she did this to heal the community, rather than to punish her father for sexually abusing her. Almost apologizing for the movie’s popularity, Egoyan says, “It was inadvertently a really accessible film. That wasn’t planned. It just happened to work out that way.”

The recurring themes in his work form a disturbing pattern—an obsession with predatory father figures who violate innocent youth, and twisted family intrigues tripwired with secrets and lies. In Family Viewing, a son discovers his father has erased their home videos by making sex tapes with his stepmother. In Exotica, a father mourns his daughter with ritual visits to a stripper in a schoolgirl kilt, while he hires a babysitter to tend an empty house. And in The Sweet Hereafter, father-daughter incest is framed in the soft glow of deluded romance. By the time Egoyan made Felicia’s Journey—his 1999 thriller starring Bob Hoskins as a quiet monster who preys on a pregnant 17-year-old—I felt it was time to ask him what was at the bottom of it all.

Egoyan revealed that his obsession was rooted in a personal trauma—not within his own family, but involving his first love. “There was a young woman whom I adored from a very young age, and who was inaccessible to me for the longest time,” Egoyan told me at the time. “Later on, it was revealed that there was an abusive relationship with her father. I felt helpless about it. So rather than address it, I went into denial, like everybody else. I was completely, madly in love with her. From about 13 to 18.” Egoyan explained that he never let on to the father that he knew his secret, but “I had to make promises to him which I ultimately couldn’t keep—in terms of keeping my relationship with his daughter platonic. I was living a double life.”

With Felicia’s Journey, the tale of a teenage girl who falls into the clutches of a serial killer, the director’s career entered a new phase. Though the theme was close to home, it was his first thriller, the first movie he’d shot abroad, and the first he had not produced himself. Backed by Mel Gibson’s Icon Entertainment International, it was also his first fling with Hollywood, and the film that threw a kink into his charmed career. He left Cannes without a prize, which stung given that the jury president was compatriot David Cronenberg. And Felicia’s Journey became the first in a string of films that earned a fraction of their budgets at the box office: Where the Truth Lies, Ararat, Adoration, and Chloe.

But there’s more than one way to measure success. It would be hard to find a failure as noble as the wildly ambitious Ararat, which delved into the tangled legacy of Armenia’s 1915 genocide. And though Where the Truth Lies grossed just $3.5-million on a $25-million budget, it revealed a new dimension of Colin Firth’s talent. “His agent considers it was the beginning of his rebirth,” says Egoyan, explaining that director Tom Ford “saw his [Firth’s] acting chops” and cast him in A Single Man. Firth, who went on to win the Oscar for The King’s Speech, reaffirmed his faith in Egoyan by starring in Devil’s Knot.

That movie, the director grimly observes, was “pummelled” by critics who had seen too many documentaries about the West Memphis Three murders and were frustrated by the film’s refusal to find a culprit. Both Firth and Witherspoon portray characters “with no agency,” Egoyan points out. “Hollywood stars don’t do that normally. They usually turn things around and make things happen. The whole thing felt perverse. ‘You’re making this film where there is no resolution, no happy ending, where things are left in doubt? Yeah, we’ll see how it works.’ Both Colin and Reese were willing to take the risk.”

What actors love about this director is how deeply he engages them in his ideas. What’s my motivation? is one question that’s always on the table. Allergic to formula, Egoyan likes to lock the answers in the kind of richly nuanced puzzle that recalls Winston Churchill’s description of Russia—“a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.” The Captive is no exception. It began as a 60-page script that Egoyan had shelved for years and then sent to his friend Fraser, an ardent fan of Scandinavian crime novels, who lent the story the suspense and narrative rigour it needed. But with a plot hinged to video surveillance, The Captive also revisits some familiar tropes of a filmmaker who explored sex, lies, and videotape well before Steven Soderbergh. “Like every one of Atom’s movies,” says Fraser, “it’s a little machine—there’s a trap for every character.”

Egoyan’s next feature, Remember, explores stalking and captivity on a quite different level, with Christopher Plummer cast as a 90-year-old Holocaust survivor hunting down a Nazi war criminal. This is the director’s eighth film with producer Robert Lantos, who made The Sweet Hereafter. And given the pedigree of the subject and the star, it may well take him back into Oscar contention.

But in the end, Egoyan often seems most excited about dabbling well outside the mainstream. Before I leave, he eagerly shares a video clip he shot with his BlackBerry. It shows the back of woman’s head, swaying at a rock concert; he’s making a short dramatic film around it, about a missing girl. Two of Egoyan’s most affecting films are Calendar (1993) and Citadel (2006), lo-fi travelogues in which Khanjian gets to play her vivacious, irrepressible self, so unlike her constrained characters in Egoyan’s other films. Calendar and Citadel serve as ancestral odysseys for this remarkable couple—both immigrant kids of Armenian parentage, they have been together since 1984, when Egoyan cast Khanjian in his first feature. Calendar is a meta home movie that follows them through Armenia, as they unravel their roots and their marriage. In the unreleased and more personal Citadel, which Egoyan narrates as a postdated letter to their son, Egoyan relentlessly stalks Khanjian with a digital camcorder through Beirut, her childhood home. “That,” he says, “signalled the end of a compulsion to shoot her.”

Cannes is the ultimate test for a filmmaker’s ego, a world stage where even the highest honours can come with a catch. “There’s always someone around who will tell you it’s not high enough.”

After casting his wife in every one of his first 11 features, Egoyan has not given her a major role since Adoration (2008). She does, however, have a cameo in The Captive. When Khanjian kept pushing him to explain why she needed to be in the film, he eventually said he simply liked having her attached to it. “It’s very romantic, very beautiful,” she says, “that 30 years later, he still desires this.” But being so wrapped up in each other’s professional lives has been difficult, she concedes. “It’s been a constant challenge to give meaning to the personal while we were completely swallowed up by the professional. We had to learn the hard way, coming very close to a personal breakup.”

At the Cannes premiere of The Captive, their son, Arshile, who’s now 20 and studying political science in Paris, would join them on the red carpet, helping celebrate a romance and a career that have survived in synch for three decades. Egoyan was sanguine about the “brutal” pressure of launching another film in competition at Cannes. It’s the ultimate test for a filmmaker’s ego, a world stage where even the highest honours can come with a catch. “There’s always someone around who will tell you it’s not high enough,” he says, recalling his Cannes experience with The Sweet Hereafter. “I was sitting at a café with the French distributor, and she got a phone call and started to cry. She held my hand and said, ‘I’ve got some really bad news.’ I said, ‘What?’ She said, ‘You’ve won the Grand Prize [Grand Prix, second to the Palme d’Or].’ I said, ‘The Grand Prize sounds pretty good!’ But it could have been higher. Or, you got two Academy Award nominations but you didn’t win.”

Egoyan recalls a night where he saw success turn to failure in one mortifying moment. It was at the premiere of his Houston Grand Opera production of Salome, starring the late legendary German diva Hildegard Behrens. “It was at such a high level,” he says. “I was sitting back watching the show, thinking I’m really a brilliant artist. Then there’s this moment where she goes up on a swing and the skirt unfurls to become a screen for eight minutes of flashbacks. That night, the skirt fell. It unsnapped from the swing. So there were all these backlit projections with nothing for the images to go on—except the big hairdos of the Houston ladies looking at each other, wondering why suddenly there were stagehands crawling around in jeans with their butt cracks showing, and thinking it was intentional. You can’t stand up and say, ‘This isn’t what is supposed to be going on!’ ”

It was a nightmare, yet as the director looks back on it, framing the memory in his mind’s eye, you can see him relishing the dark irony of an artwork escaping its creator, Frankenstein fashion, absurdly framing his hubris. A scene that would be at home in a film by Atom Egoyan.

Grooming by Kevin Smith for JudyInc.com using TRESemmé hair-care products.