Camellia, the Eternal Code of Chanel

How a flower came to be the emblem of the French maison.

The camellia first appeared as a motif in Gabrielle Chanel’s collections in 1924, and today it continues to blossom through the artisanal know-how of Lemarié. The Lemarié atelier is full of quiet talent. The artisans, known as les petites-mains, possess artistic skill and manual dexterity. Here, in the complex that is 19M, Chanel’s craftsmanship hub on the outskirts of Paris, the flower specialists are sculpting blooms in the same manner Lemarié founder Palmyre Coyette did in 1880: by hand. The ambiance is unlike almost any other state-of-the-art workplace as there are no computers to be seen. Rather, les fleuristes, crouched over white tables, are hard at work fashioning camellias, said to have been Gabrielle Chanel’s favourite flower.

“I like to work with my hands and have the patience for this craft,” one of the Lemarié artisans says. “People imagine we are old, and this is an old decoration,” she explains in her hesitant English, but the average age of the workers is just 30, and with 80 people, the workrooms buzz with activity.

Lemarié is one of the handful of specialist artisan ateliers bought by Chanel from the mid-1980s to early aughts to safeguard the endangered savoir faire. Chanel established the Paraffection subsidiary (loosely translated “for the love of”) for the acquisition of these ateliers, thereby ensuring its future. Today, Lemarié makes 40,000 camellias per year for Chanel from silk, chiffon, satin, organza, velvet, tweed, leather—the list of fabrics goes on and on and on—using special tools to shape each petal. A Lemarié artisan must apprentice for five years to be considered “a real flower maker.”

The camellia originated in Southeast Asia and was cultivated for hundreds of years before its introduction to Europe. Gabrielle Chanel may have first noticed the flower as a teenager when she saw Sarah Bernhardt perform in Alexandre Dumas’s The Lady of the Camellias, an interest later strengthened by receiving a bouquet of camellias from Arthur “Boy” Capel, an English polo player who became her lover and muse. A photograph from 1913 shows Chanel at the Étretat seaside in Normandy, with a fresh flower slipped into her belt. Her Parisian apartment at 31 rue Cambon was frequently decorated with bouquets of camellias and remains home to Coromandel screens embossed with the bloom as well as a chandelier with crystalline replicas. The camellia first appeared as a motif in her collections in 1924, and today it continues to blossom through the artisanal know-how of Lemarié.

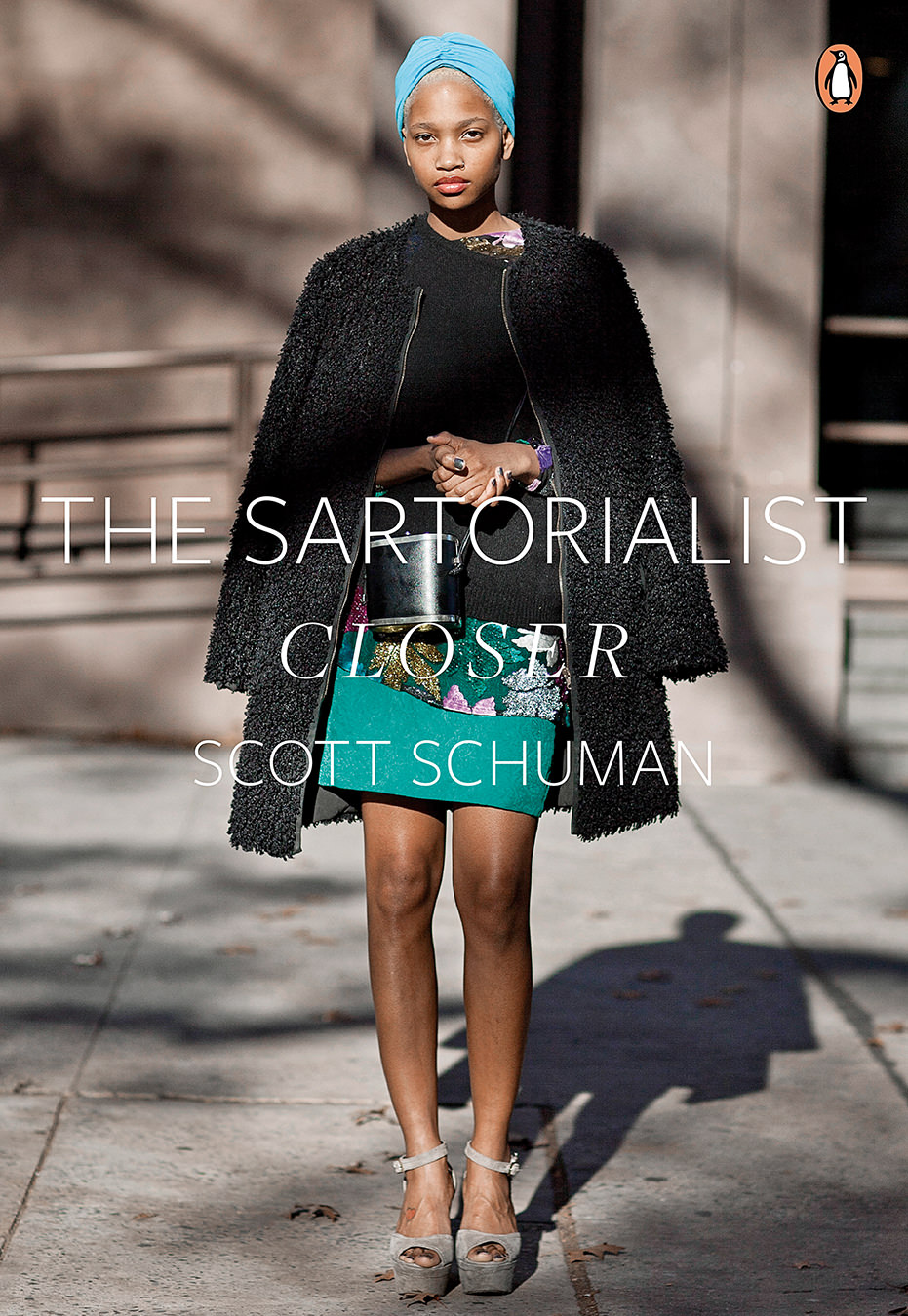

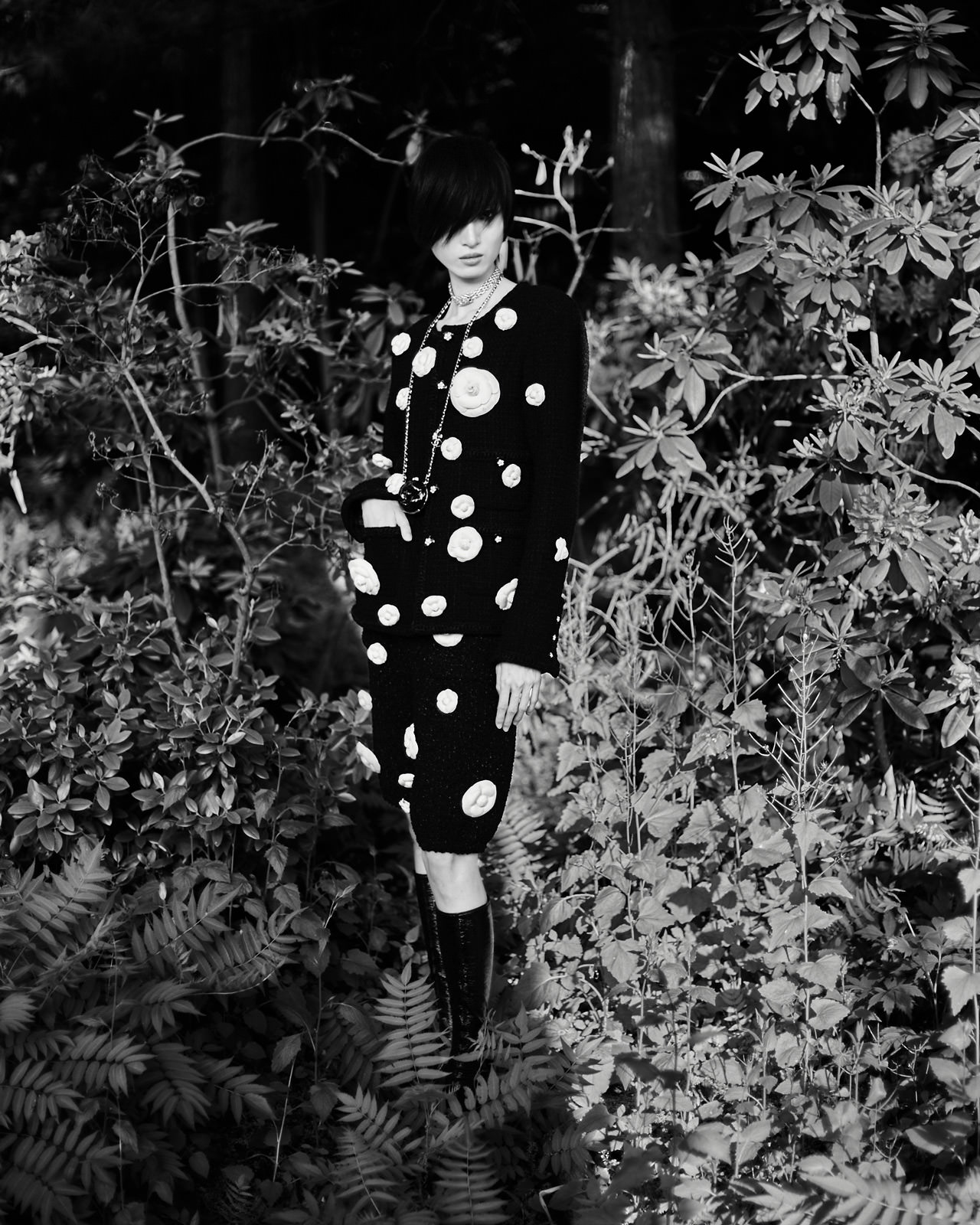

Look 10 from the Chanel fall/winter 2023 ready-to-wear collection.

Chanel never explained her penchant for the camellia. It might be because it has an undisputed beauty, flowers during the winter, is considered auspicious, and has no scent to overpower her perfume No.5 (released in 1921). Whatever the reason, the camellia is synonymous with the House of Chanel. The flower has been fashioned from too many materials to count, used to adorn fabrics, transformed into jewellery as in the Chanel Camélia high jewellery collection, appeared on watches like the Première Camélia Skeleton that showcases the Calibre 2 movement in the shape of a camellia, and even included as an ingredient in the brand’s skin-care (Hydra Beauty line) and makeup ranges (think Rêve de Chanel illuminating powder). Karl Lagerfeld’s wedding dress from the fall/winter 2005 haute couture collection was embroidered with 4,000 camellias.

The “camellia is more than a theme,” notes creative director Virginie Viard. “It’s an eternal code of the house.” For the Chanel fall/winter 2023 ready-to-wear collection, silk camellias adorned slingbacks or embellished the pocket or collar of a classic black coat. The models wore silk camellia hair clips, had diamond-encrusted camellia earrings, and swung camellia handbags in black, white, pink, and red. Romantic maxi dresses were printed with the motif, and jackets were dotted with removable camellias.

“Each collection is an opportunity to discover new things,” says another Lemarié artisan, who has been with the company for 10 years. “The demands change with every collection, but the métier is the same.” Adjustments are based on the type of fabric. And while recycled textiles and polyester are being shaped into camellias, the synthetics make it hard for les petites-mains to shape the petals as these fabrics cannot be starched (the sequined mesh camellias for the 2022/23 Métiers d’Art Dakar show were especially challenging). “We still stay with natural fabrics such as silk, cotton, linen, leather.”

Be it a signature black-tweed jacket embellished with blooms that look so abundant you might expect the petals to drop, a simple white T-shirt with a camellia insignia, or even a paper shopping bag with a paper camellia adhered, this is one flower that never wilts.

Model: Jiayan Yao with Sutherland Models. Hair and Makeup by Ronnie Tremblay.