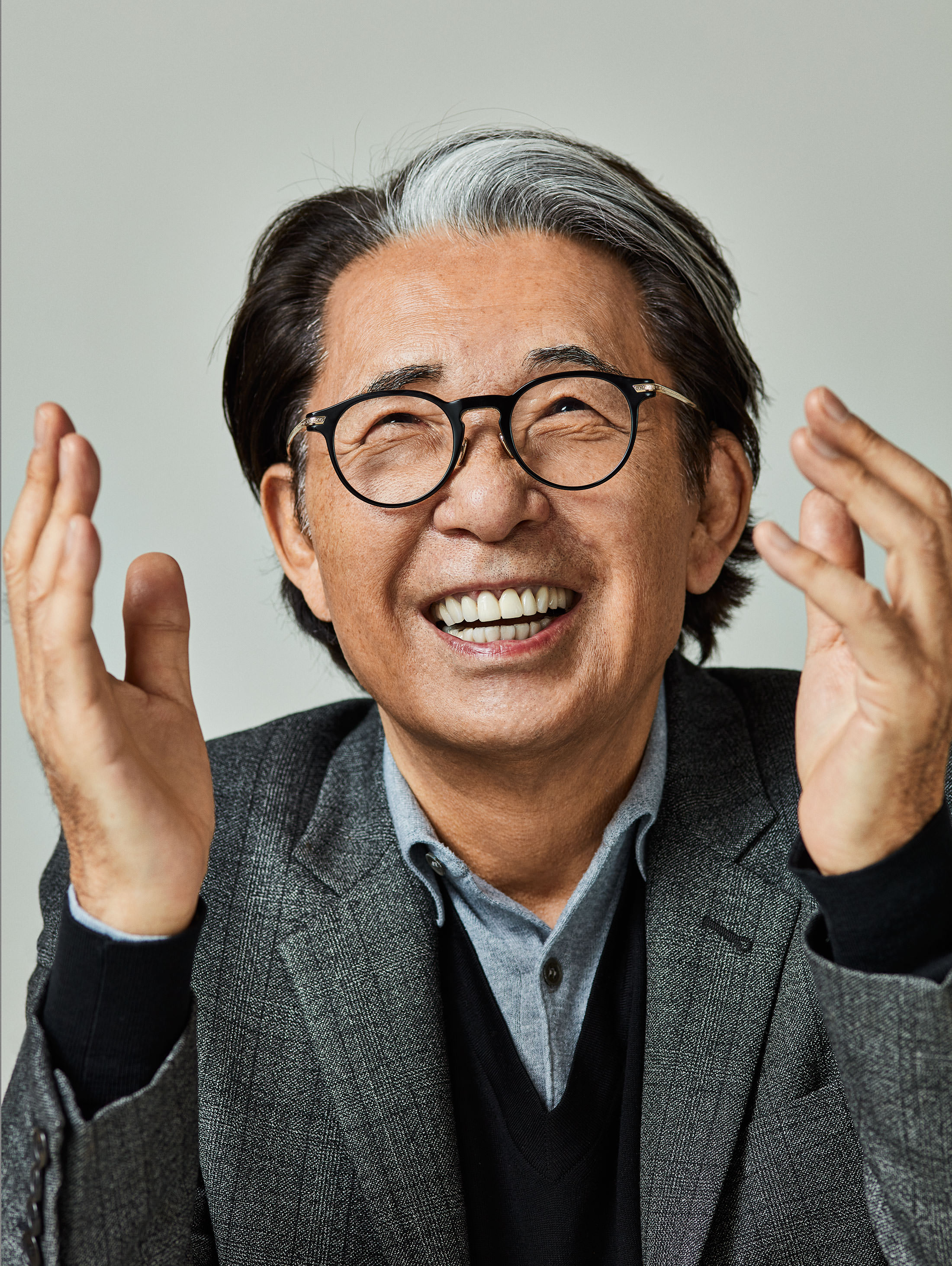

Kenzo Takada On His Creative Life

Colourful life.

“I’m looking at a wall of 50 sketches at the moment,” says Kenzo Takada, with a note of trepidation in his voice. “It’s been good to get back into designing clothing. Well, from time to time, it is.”

Takada says this as though he’s forgotten how. And, in a sense, he may have. It’s been nearly 20 years since he stepped down as the creative head of the namesake label he founded in Paris in 1970; he sold it to LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton in 1993 for a reported $80.5-million (U.S.). Kenzo had by then become a distinctive and influential force in high-end fashion. So, getting back to designing clothes—or, more specifically, costumes for the Tokyo Nikikai Opera Foundation’s production of Madama Butterfly at the end of the year—has been mildly shocking.

“When you’re designing clothes for the public to wear, you actually have to think very practically, much more so than the idea of fashion suggests,” explains the 80-year-old creative. “How will the garment fit? How will it wear? Designing costumes for opera is all about visual impact, but that’s interesting in its own right. Does it fit in with the set decoration? What’s it like to move in?” Takada (who, annoyingly, looks closer to 60-something, a youthfulness he ascribes to yoga and working less) has never given up designing. While the Kenzo label has continued, until recently under the leadership of Opening Ceremony’s Humberto Leon and Carol Lim (a new creative director has yet to be announced), Takada has turned to the home. He’s created furniture collections for French manufacturer Roche Bobois, including a reimagining of the brand’s iconic 1971 Mah Jong sofa inspired by the traditional kimonos in Japanese Noh theatre. And he has a homewares collection set to launch this year too, the details of which he’s keeping under wraps.

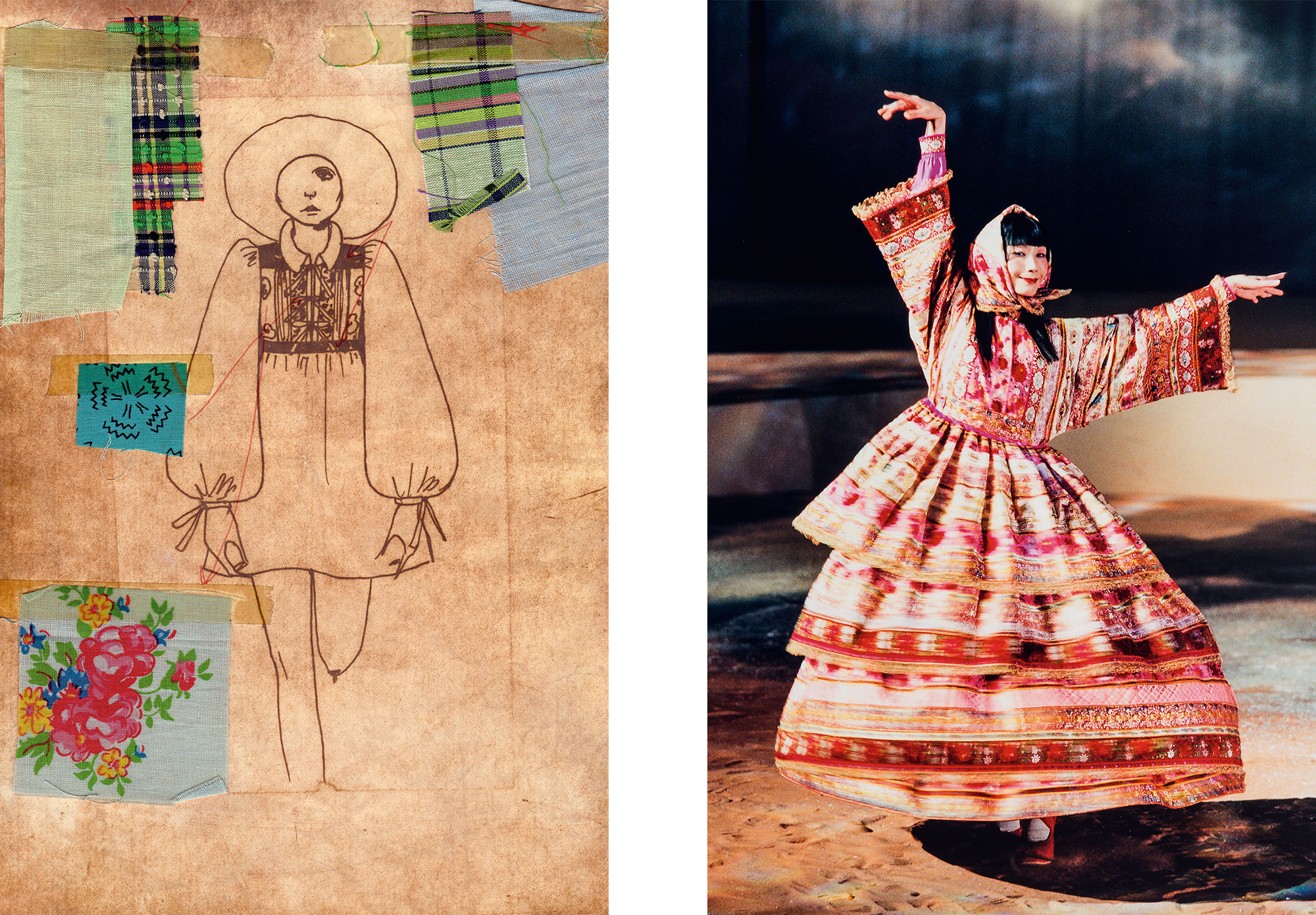

Earlier this year, ACC Art Books released Kenzo Takada by Kazuko Masui and Chihiro Masui, a monograph of his work comprising a catalogue of his original sketches, rather than the typical catwalk photos. “I love sketching,” he enthuses. “Some days, though, it just doesn’t come. When you sketch, there’s a really physical aspect to the process. It’s where the ideas are generated, but it’s also the start of the process of seeing lines on a piece of paper manifested in actual clothing. And that’s the greatest feeling—seeing someone in the street wearing something that’s started out as your sketch.”

“I never really hoped to actually work in fashion in Paris because I kept being told that it would be impossible for a Japanese person to do so.” —Kenzo Takada

The beginning of Takada’s career in fashion was a litany of obstacles to be overcome. Indeed, his advice to those starting out is to always have a goal, “To really push for it and to be ready to break a few boundaries along the way, if that’s what’s required.” First, he attended Bunka Fashion College in Tokyo and when he enrolled in 1958, it had only just begun to admit men. His father was opposed to the idea, but his mother knew how much he loved to draw and so she encouraged him. “Men just weren’t accepted in the fashion world [in Japan] back when I applied to the college, and so there were no real jobs [for men] either,” he says. “In fact, there wasn’t really much in the way of ready-to-wear for men. Now I look back, applying for a place felt like a brave thing to do.”

In 1970, when Takada opened his first boutique in Galerie Vivienne, he originally had called his fashion label Jungle Jap (the store’s interior was inspired by Henri Rousseau’s 1910 painting, The Dream).

In late 1964, after graduation, Takada decided he had to experience Paris. A shortage of money meant he’d make the two-month-long journey by boat rather than flying, and included stops in Hong Kong, Bombay, and the African country of Djibouti. Despite the arduous trip, he expected to be back in Japan within the year. “It was really just a dream for me to go to Paris,” says Takada. “There was the nouvelle vague, and Paris was in all the movies I watched. It was 60 years ago, but I still remember arriving at the Gare du Nord and thinking, ‘My god, I’ve made a big mistake here.’ Everything was so dark and dirty. It was only when I got to see Notre Dame illuminated that I changed my mind.

“But I never really hoped to actually work in fashion in Paris because I kept being told that it would be impossible for a Japanese person to do so,” Takada adds. “There was this sense that nobody from Japan could be competent. So I thought I’d just be there for five or six months—that was before I found I could make a living as an illustrator.”

Despite picking up illustration work for Louis Féraud, as well as editorial for the likes of Elle—he had, appealingly, as different a take on illustration as he would have on clothing—Takada necessarily lived frugally. Ironically, given his more recent design pursuits, it took five years before he’d buy a sofa for himself, on credit, and for some time it was the only seating he had in his apartment. Yet slowly, making clothing started to seem like a possibility, though it would have to be on the cheap.

“Looking back, I think it was also because I was looking for some kind of identity as an outsider that I wanted to bring something very Japanese into it all. It’s strange that, even though I’m Japanese, I think most people think of me as a French designer.” —Kenzo Takada

Indeed, it was his circumstances that shaped the aesthetic of bold colours and clashing patterns for which Takada would become known. Without the contacts, let alone the money, to acquire high-quality textiles, he would pick up whatever affordable pieces of cloth he could find at Marché Saint-Pierre, a fabric emporium in the 18th arrondissement in Paris, which imported more traditional, often floral Japanese textiles. This mix of European sensibility and Japanese fabrics was like a clash of the Orient and the Occident and a new way of doing things at the time. “That [mixing of cultures and fabrics] ended up having a big impact, because it helped me define a style for myself,” he says. “Looking back, I think it was also because I was looking for some kind of identity as an outsider that I wanted to bring something very Japanese into it all. It’s strange that, even though I’m Japanese, I think most people think of me as a French designer.”

In 1970, when Takada opened his first boutique in Galerie Vivienne, he originally had called his fashion label Jungle Jap (the store’s interior was inspired by Henri Rousseau’s 1910 painting, The Dream). The name was meant to invoke the eye-catching exoticism of Takada’s clothes and, cheekily, to underscore the heritage of a designer who’d been told he would never make it in Paris. Still, this got the culturally sensitive fuming: Japanese protesters hoisted placards outside Macy’s in New York, where Takada was set to hold his first major fashion show in 1972. He heard their arguments and agreed to change the name and thus, Kenzo.

Ultimately, perhaps, design won the argument, especially since Takada’s vibrant, easy-to-wear clothing offered a distinct contrast to the somewhat pedestrian traditionalism of the clothes being produced by Chanel, Dior, and the other couture houses that dominated French fashion at the time. But that was not the only way in which Takada was a pioneer; other Japanese designers followed suit and ventured West. And once Takada’s Kenzo label had made a splash—a hot ticket for the cool crowd, with the likes of Jerry Hall and Grace Jones clamouring to be his muses—Parisian fashion houses started to include Bunka graduates in their hiring, with the likes of Yohji Yamamoto subsequently gaining a foothold in Europe.

Left: A sketch from the Kenzo spring/summer 1971 collection with swatch samples, ©Archives Kenzo. Right: As published in the coffee table collectible Kenzo Takada, a wedding dress (right) from the Kenzo fall/winter 1982 collection, ©Richard Haughton.

It was Takada who brought in the then-radical idea of allowing people to buy directly from a catwalk show, even if, he says, the idea was driven more by the need for cash flow than a desire to buck the system. And he’s the one that came up with the high/low fashion collaboration, working with the mass-market retailer The Limited, a polemic move at the time that saw a number of his stockists refuse to reorder from him. Kenzo was also one of the first labels to have a global hit with a fragrance, called Flower. Perhaps above all, Takada pursued affordability in designer clothing. Long before he decided to sell his company—a tough decision he describes as both “political” and personal, marked by the death of his mother and partner—his impact on the wider fashion world had become abundantly clear.

“I’m not sure young people today know much about where the ideas in their clothes come from,” notes Takada, “because everything moves so fast. But I’m proud that maybe I brought something worthwhile to the world—a touch of joie de vivre, a bit of a change. If I made one major contribution to fashion, it was helping to bring some accessibility to it. What I did wasn’t exactly basic, but it wasn’t couture either, and this was at a time when French fashion at least was really all about couture. It created a new market, in a way. At the time, you don’t really realize that what you’re doing might be in some way new because everything is going so fast. That said, I consider myself really lucky, though, because it was exactly the right time for what I happened to do.”

But for all his nostalgia, Takada is not, it seems, one to have regrets. He says he often muses on what might have happened if he hadn’t sold—“[the company] might have gotten much bigger, or, of course, it might have crashed. It’s hard to say,” he reflects, sanguine on the matter. He takes pleasure in seeing the label around, even though he’s not involved in it anymore.

“It was awkward in the beginning, seeing these clothes carrying my name, but which I hadn’t designed,” he says, smiling. “But, you know, I got used to it.” Besides, he’s moved on with his own wardrobe. While Takada may have given fashion a much-needed injection of colour and pattern, these days he’s most likely to be found in dark, sober shades.

“It’s strange, but as I’ve grown older, I find that I’m wearing more and more monochrome,” says Kenzo Takada, joking that the biggest advantage of leaving his own label is the freedom to wear other designers’ clothes. “Sometimes there’s a touch more colour for me in the summer, but essentially these days I’m all black and grey—and I don’t know why,” He laughs. “Maybe it’s that unspoken rule, you know, that Japanese designers all have to wear black…”

_________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter, here.