A Tale of Post-Internet Publishing: Turning Controversy into Verse

What happened to the book?

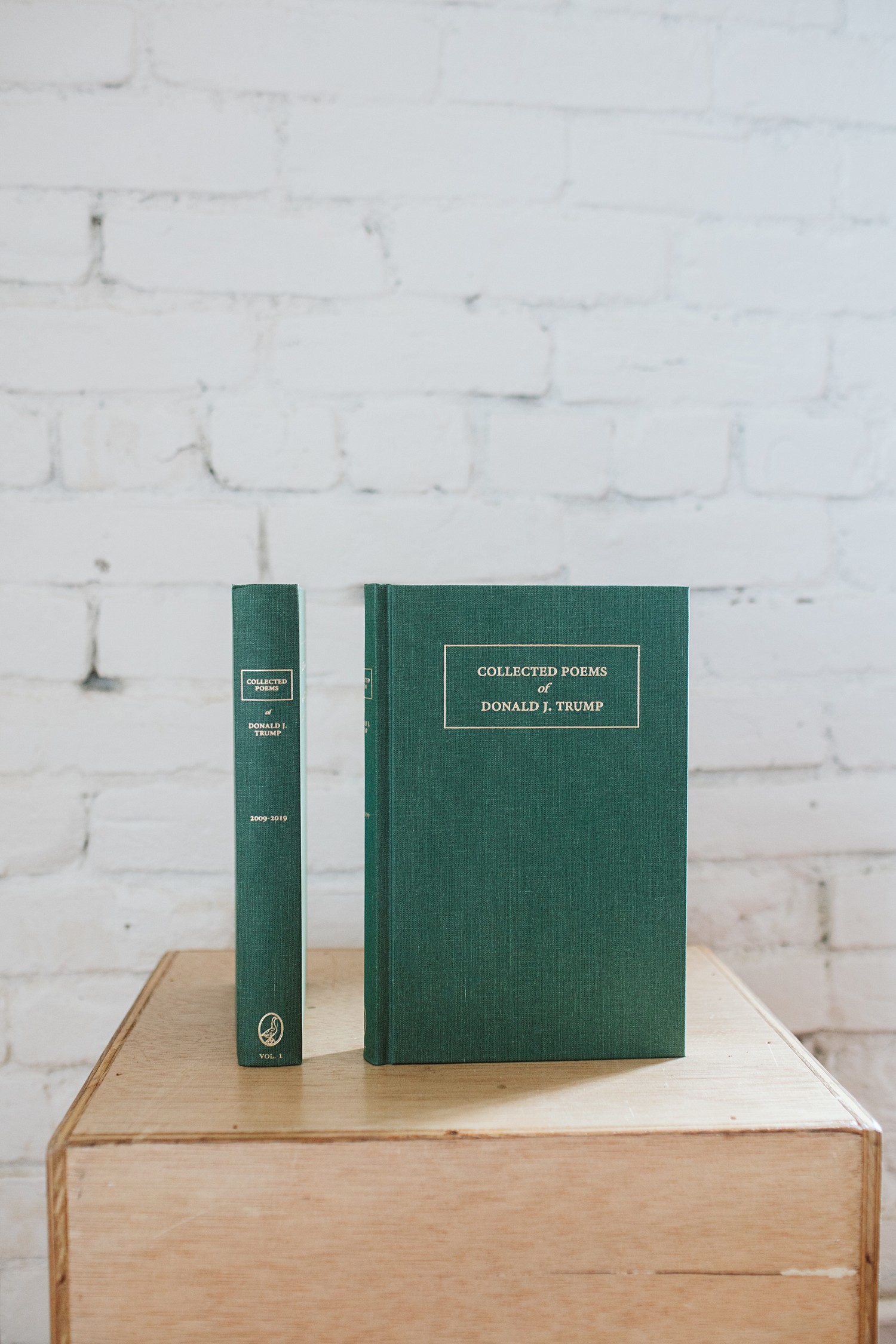

Turning the book over in my hands and contemplating the sage-green cloth, gold-foil embossing, and silk page marker, it’s hard to reconcile the beauty of the object with the title: Collected Poems of Donald J. Trump—a collation of tweets carefully placed on a page word by word to create concrete poetry. The cascading verse is actually quite brilliant at first glance, and I don’t know what to do with that.

Immediately, I am faced with the consequences of the interplay between the idea of the book and this unfathomable thing, the Internet. There is a change taking place in the publishing industry because of the Internet. That change made this book possible. What has happened to the book?

When faced with information overload, as we so often are, it is our tendency to reduce information to its least common denominator. What can we take in from this and what can we push away? For me, faced with this book and its many implications, the simplest summation I can muster is that somehow removing the tweets from the context of Twitter has made something contentious beautiful and valuable. Taking the flippancy of Twitter and foregrounding it on white space has given the words more authority.

When I ask Richard Cavell, co-founder of the UBC Media Studies program, he points to the shift in media as its own example of information overload. “What they’ve done here is the classic example of an information overload society,” he says. “Taking some information and taking it out and placing it on its own, forces you to look at it very carefully. Otherwise this information’s just going over our head all the time.”

Books, on the other hand, are tangible, un-muteable, un-blockable, unavoidable.

Twitter is like a microcosmic representation of people trying to cope with information overload. Public figures distill their thoughts on the state of affairs into 230 characters, usually less, and society, in turn, chooses what to tune in and out of. On Twitter we can keep scrolling, log off, mute or block the person, and move on without having to think about the effects on material reality. Books, on the other hand, are tangible, un-muteable, un-blockable, unavoidable.

As Cavell suggests, perhaps even the act of reading a book is like an antidote to information overload. To read, our eyes must push away the white background and pull the black text toward us. When reading poetry in a book, you are pulling challenging arrangements of words toward yourself, with no choice but to engage or close the book.

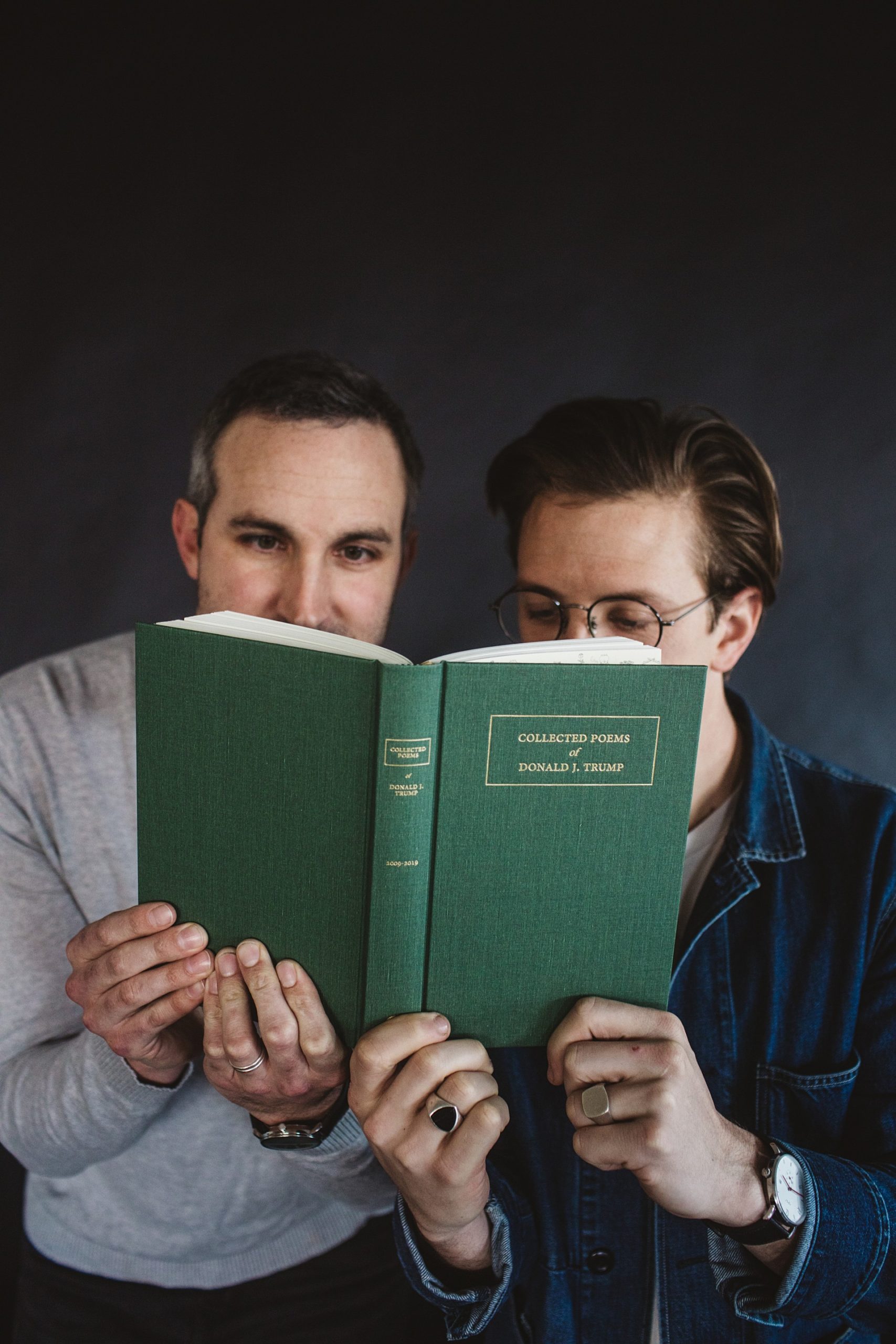

The same idea was certainly top of mind for photographer Gregory Woodman when he and his colleague Ian Pratt set out to create Collected Poems of Donald J. Trump. “I didn’t repackage the poems into tweet form where they’re easily accessible and you can scroll past,” Woodman, explains. “I made it in a medium where you have to put it in front of you and wrestle with it. You have to pass it back and forth between two humans and talk about it face to face. You can’t just tweet about it and log off.”

The words “create” and “repackage” are key to understanding what has happened to the ideological concept of the book. The two are not writers; they repackaged what already existed in order to make a statement, a tactic that poets and post-Internet artists like Kenneth Goldsmith and Jon Rafman have been using for years. In making the collection, Pratt and Woodman created a work of post-Internet poetry—poetry that shares the conditions created by the Internet.

The shift from tweet to concrete poetry also allowed Pratt (left) and Woodman (right) to copyright the words.

Beyond creating a physical example of information overload, the book is also a representation of how the untenable Internet is influencing the way we conceive of and interact with traditional ideas like books and poetry, and institutions like publishing.

According to Cavell, by using Trump’s tweets, Woodman and Pratt’s project positions tweets as the new sonnets. He notes that both the tweet and the sonnet adhere to a strict form (substituting quatrains and rhyme schemes for character limits) and, like Shakespeare, are unedited by a culturally ordained publisher.

Regardless of what we name it, the manipulation of the text from tweet form to book of poetry form creates a shift in meaning, and it is one that does not sit well with people.

Not that Woodman and Pratt care—controversy is a bedfellow of poetry and exactly what they wanted. When they set out to create the collection, their intention was to dance on the razor’s edge. Woodman admits: “We wanted to make sure we weren’t leaning one way or another because I think that’s where the power is—not just getting one side to confirm their bias and nod in agreement but with both sides getting a little bit of ‘I love this’ and a little bit of ‘I hate this’. I think that that’s actually a more responsible viewpoint in general.”

Responsible or not, it certainly isn’t a viewpoint that is often found on the Internet, least of all Twitter. “There are no lukewarm takes on the Internet,” he laughs. “Moderation isn’t sexy.”

Unfortunately, he is right.

Removed from the context, the poetry is arguably “good”. But we aren’t ever able to remove the work from the context of politics or Twitter; even in book form, the subject matter and absurdity of Twitter will never be considered “normal”, which Woodman says some people fear. They needn’t worry, because poetry isn’t normal. The strangeness of poetry, the inaccessibility and oftentimes cumbersome method of communication, negates any chance of this book being considered “normalizing”.

That said, it does to some extent aestheticize the sentiments within. The short, simplified prose is reminiscent of Rupi Kaur. In imitating her style, the words’ appeal, fear, conviction, and fractiousness are re-appraised through a process of curation—one that falls in line with the curation that we are experiencing in today’s world on Instagram, Pinterest, Goop, and in marketing. We respond to aesthetic, and the genius of the book is in its ability to manipulate us into paying very close attention to what we absorb, what we approve of, and why. It also makes us wonder why the migration of the tweets to the page feels so official.

So which publishing house endorsed releasing this thing anyway?

As it turns out, none.

I first met Woodman and Pratt in Aspen after someone mentioned offhandedly that the photographer with the killer mustache (Woodman) had published a book. On the spine is the embossed emblem of a golden goose to represent the publishing house that, until six months ago, didn’t exist. A publishing house that, by all traditional criteria, still does not exist. And when Woodman nonchalantly told me they had sold 700 copies through Instagram promotion alone, I politely gawked. Before the time of Instapoetry messing with the curve, award-winning poets were considered a success after 500 copies sold.

Of course, self-publishing is a burgeoning market to some and an ever-encroaching beast to others (read: publishers and traditional authors), but the truth is: it is a democratizing tool for artistic expression and political critique. Woodman and Pratt are living, breathing examples of what the Internet can create when gatekeepers are removed from the process of creating literature. Not only that, but the pair tapped into the “self-published” nature of Twitter with their subject matter and migrated it into a sphere that feels more culturally valuable, only to then promote the book on the Internet. The irony is palpable.

Even with the vast, uncontrollable space of the Internet, we haven’t completely moved on from books, but we do feel differently about them. To a literati desperately clinging to antiquity, self-publishing may be conceived as less valuable or it may feel like the Internet is the end of literature and publishing. It’s not. The Internet has not destroyed literature or publishing, it has opened it up and created a moment of enormous promise—heralding a media shift where self-publishing and fan fiction are the new books.

And old books are no longer just books; they are fetishized as collectable, displayable, beautiful things. We see this movement on Bookstagram or Booktube where people artfully arrange their objects with tea or do hauls of the latest book and talk about how their to-be-read piles are getting unmanageable. The image or mere existence of the object serves the same purpose and provides the same satisfaction as reading it. And the existence of this book, even on a coffee table, has weight.

As a last act of defiance, Collected Poems of Donald J. Trump can upset you before you even crack the spine, and as far as Woodman and Pratt are concerned, that is enough for them to call it a job well done.

________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter here.