There is a moment in James Cameron’s new film Deepsea Challenge 3D where viewers might ask themselves, “Why is he doing this, again?”

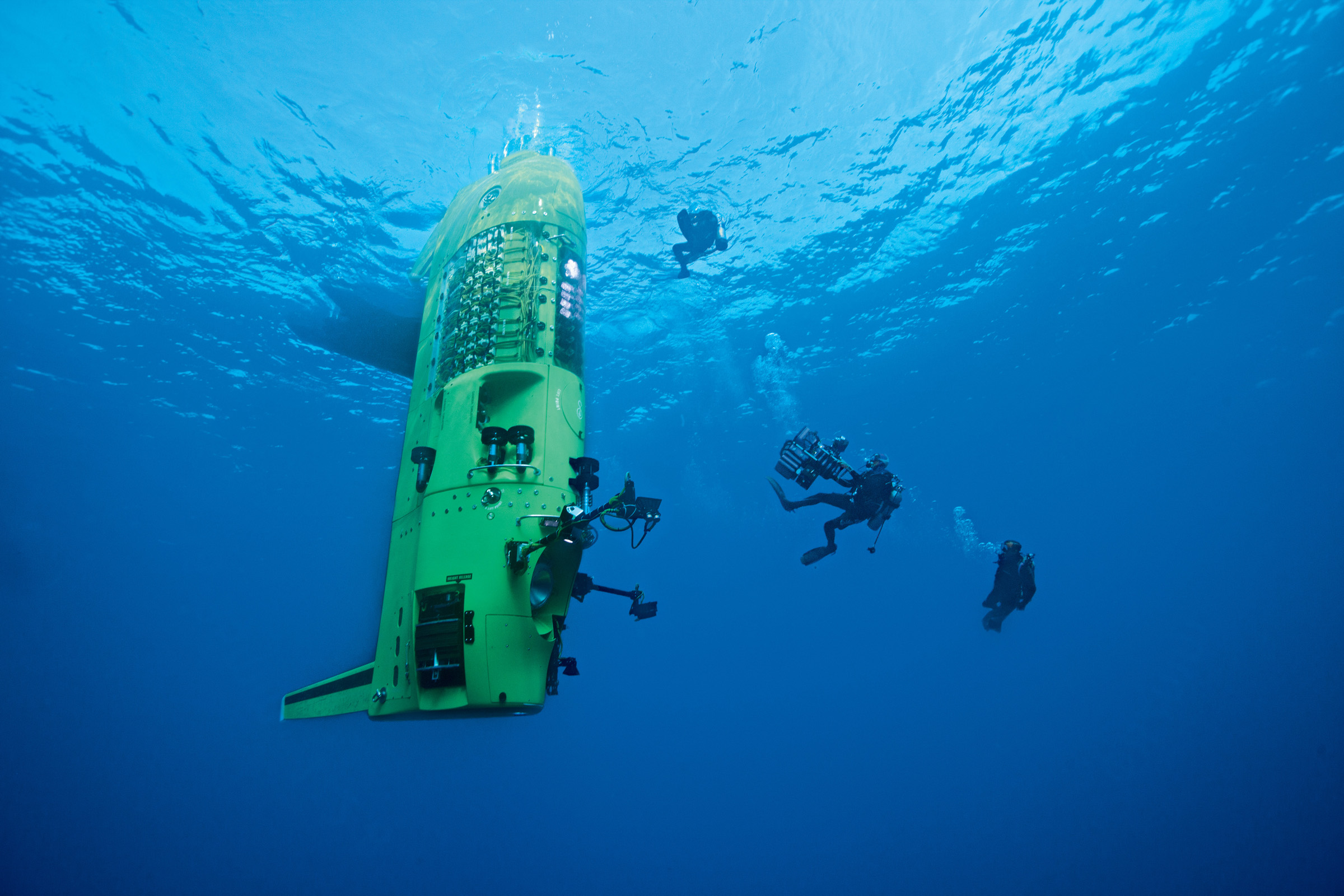

Cameron kisses his wife and waves goodbye to his expedition team (“See you in the sunshine”), before hunkering down in the Deepsea Challenger submersible that will take him to the deepest part of the ocean. As the hatch closes, the Canadian filmmaker begins a solo, 11 kilometre journey down into the depths of the unknown to Challenger Deep, a point located in the Mariana Trench just southwest of Guam. The successful mission on March 26, 2012, was seven years in the making, and the film Deepsea Challenge 3D is its creative offspring.

To say that the 59-year-old (Cameron turns 60 on August 16) is passionate about the ocean would be an understatement. “I was actually making Avatar the same time the sub was being built so I would, on my lunch breaks and after hours, get on video teleconferences [to] monitor it all remotely,” says Cameron, who was in New York this week for a pre-screening gala at the American Museum of Natural History.

The expedition was organized with National Geographic, supported by Rolex, and depended on a team of talented engineers and scientists to design the bright green deep-sea sub. The tried-and-tested structure had to contend with variables such as cold temperatures, hazardous deep-sea pressure, the potential of fire or system faultiness, and the looming factor of sheer unpredictability.

“For a very long time we kept the sub a secret, because we didn’t know if we would hit engineering hurdles that we couldn’t overcome,” says Cameron, who had logged countless hours of training in order to master his solitary role in the driver’s seat. “It’s taken me a while to realize that the expeditions and the movies are really the same, if you boil them down. I’ve got a small team of people and we’re solving a problem that nobody’s ever solved before—and that’s fun.”

The filmmaker is no stranger to making water-centric movies—1997’s blockbuster Titanic; 1989’s The Abyss—but it’s the first time Cameron himself has held the starring role. The filming process (which he equates to “basically taking selfies underwater”) used an ultra-small, full ocean depth-rated stereoscopic camera, developed specifically for the expedition, to bring audiences along for the 3-D ride.

Cameron’s mission followed the legacy of U.S. navy lieutenant Don Walsh and Swiss oceanographer Jacques Piccard, who completed a manned descent to a similar depth in 1960 at the helm of their bathyscaphe Trieste. (Cameron is the first person to ever undertake the journey solo.) At that time, a Rolex Deepsea Special timepiece was strapped to the hull and came up for air still ticking. In an ode to that timepiece, Cameron’s Deepsea Challenger also carried with it a new, experimental wristwatch called the Rolex Deepsea Challenge, which was attached to the manipulator arm in the open water. It, too, successfully worked throughout the voyage.

A new version of that Rolex Deepsea Sea-Dweller was announced this week, and timed to launch with Cameron’s film. “This watch echoes your dive, Jim,” said Arnaud Boetsch, Rolex’s communication and image director, presenting the filmmaker with the new blue-backed timepiece before the gala premiere. “It goes from deep-blue to black, making it the same colour as what you see outside of the Challenger.”

Indeed, that murky view of the ocean floor appears almost barren and moon-like in the film, but Cameron’s single mission uncovered a total of 68 new biological and geological specimens that had never been seen before. (Movie audiences are left lacking a real sense of what those species are, however, as the screentime is given primarily to Cameron himself.)

The question of “Why is he doing this?” is answered beyond any shadow of a doubt by the time the credits roll. “Down here there is a purity, a sense of the vastness of all we don’t know,” says Cameron in the film. “The power of nature’s imagination is so much better than our own.”