Capturing the Macabre During the Day of the Dead With Photographer Fernando Armenghol

Life and death.

“I have a terrible fascination with death,” says photographer Fernando Armenghol. “And at other times, I have a compassionate semblance of life.”

The travelling artist is known for his images of magical realism that reveal the theatrics of Mexico’s most celebrated traditions. As a Mexican and Oaxacan, Armenghol says he is in constant communion with his culture, using photography to tell stories. Moving from analogue to digital, he shoots in black and white for its rich tones that remind him of a bygone era in Mexico.

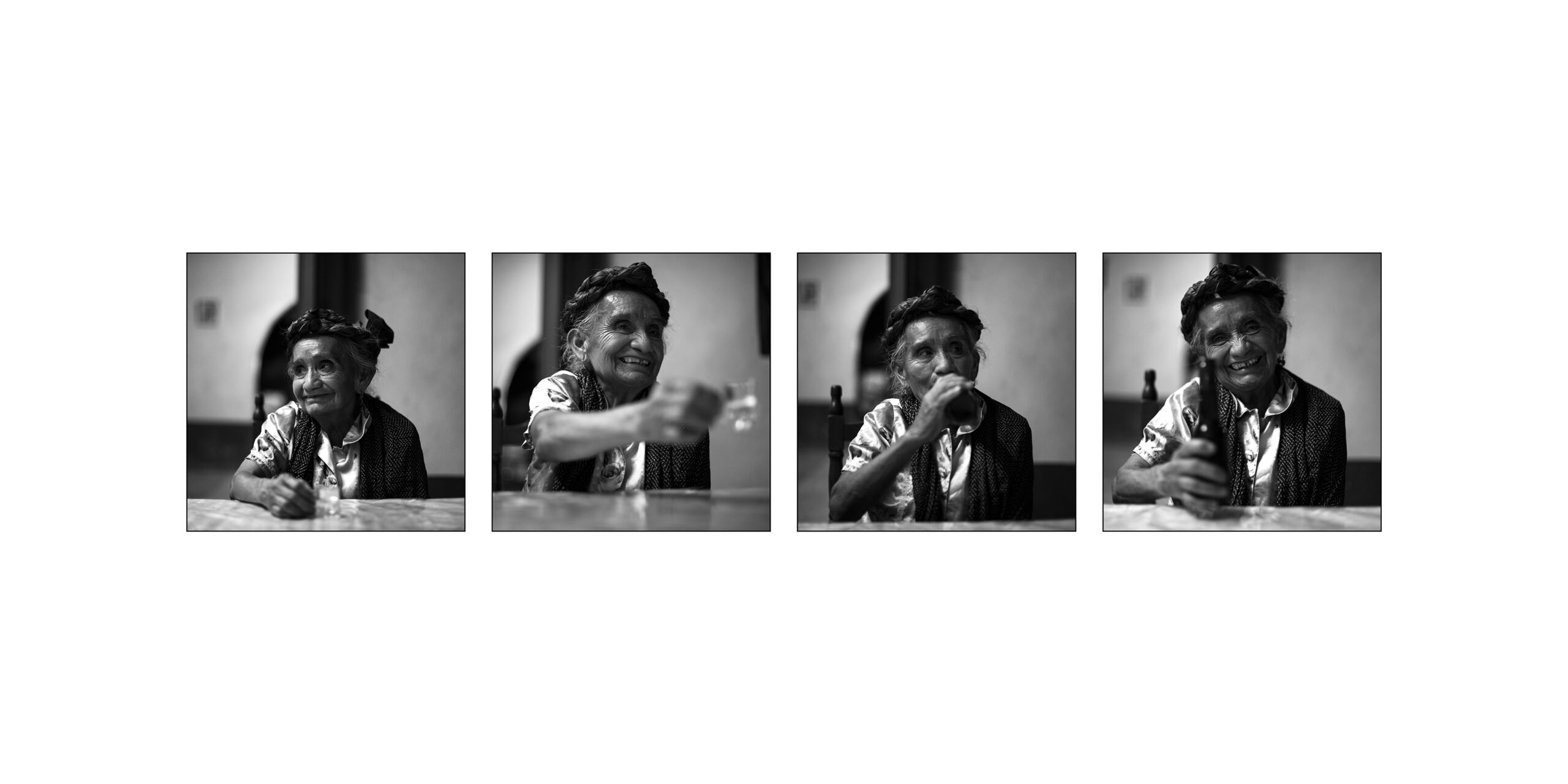

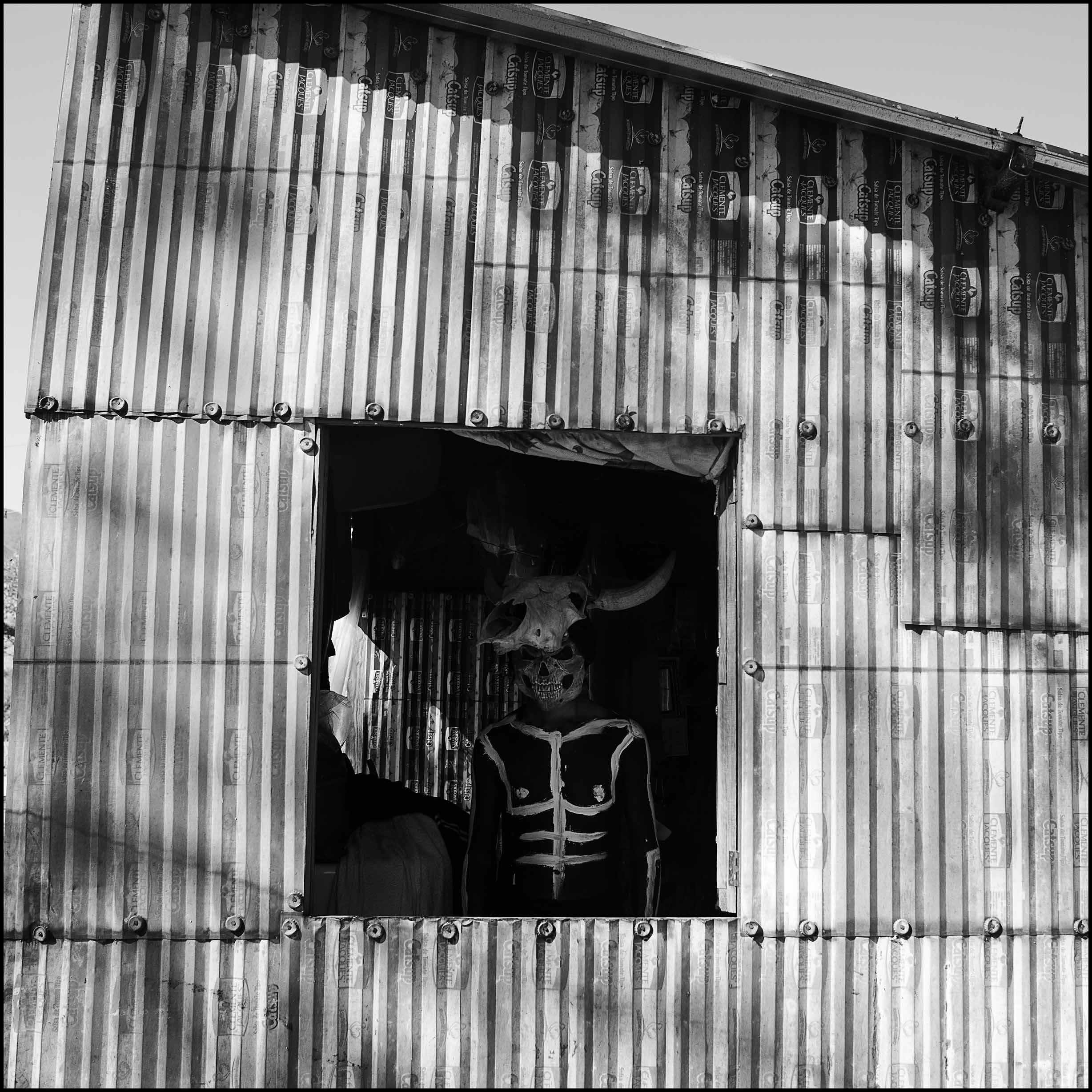

Rooted in folklore, he recognizes the expansive alchemy alive in his country’s traditions that he believes make life engaging. It’s what moves him to look, click, and capture, creating “from memory, beliefs, and visual experimentations” as in his intimate profiles of a grandmother’s grief, the ritual of tasting artisanal mezcal, and within the haunting cloak reminiscent of death. Sometimes his images feel intensely distant and macabre, while others radiate with a relatable vulnerability.

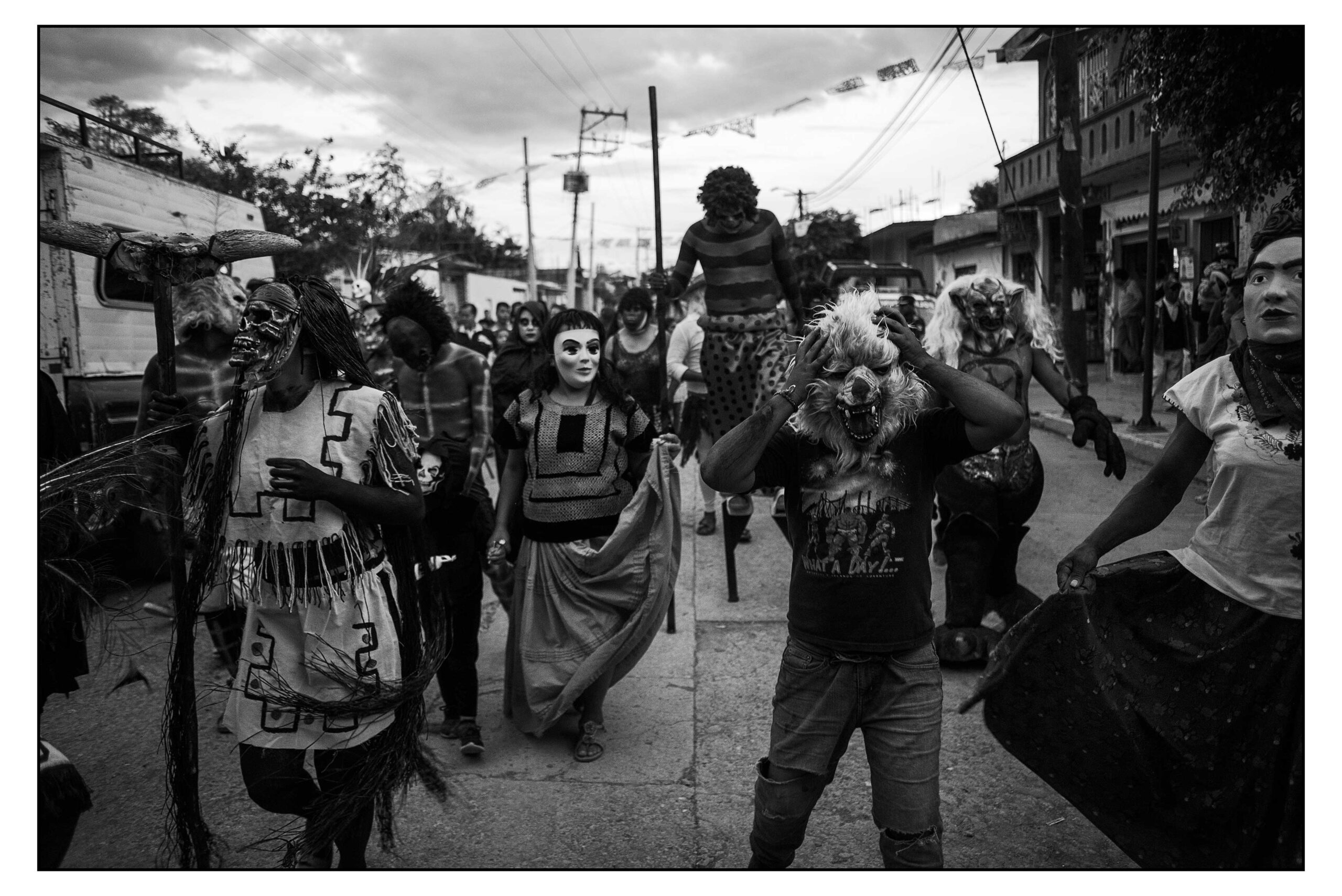

“I don’t plan my images, as I like to see what emerges from situations,” he says. “There are two Mexican festivities that have an incredible energetic charge. Carnival focuses more on the profane, while Day of the Dead is a blend of Indigenous traditions, spirituality, and devotion with a sense of humour about death.”

From October 31 to November 2, the city of Oaxaca becomes a jubilant scene to celebrate Día de los Muertos. Live music blares, ornate fashion is worn, painted faces reveal calacas and calaveras (skeletons and skulls), while marigold flowers choke the sprawling altars set with photographs and saints. Locals flood the streets to participate in rituals to honour their deceased relatives, as do thousands of international tourists who come to witness the traditions and party without inhibition.

“Day of the Dead is an accumulation of emotions, sadness, and reflections on life,” Armenghol observes. “In Mexico, we embrace death, celebrate it, and live with it thanks to our pre-Hispanic roots. It has become a mixture of Indigenous, foreign, and collective contributions of Mexicans.”

Modern festivities have been influenced by the Spanish conquistadors who blended Catholic All Saints Day and All Souls Day with Aztec traditions. “It’s a festival of paradoxes,” Armenghol says, “a mix of music and enjoyment for some, while others attend cemeteries for a scene of deep affection and respect.”

About 40 minutes southeast of the bustling old town is the Indigenous Zapotec community of Teotitlán del Valle, Tlacolula, which Armenghol visits every November. The Zapotec have lived in the Valley of Oaxaca in the southern highlands of central Meso-America since 500 BCE and still inhabit parts of Oaxaca and bordering states.

Armenghol has celebrated Day of the Dead since he was young. Imagine steaming tamales, traditional breads, mole, and mezcal savoured in the glow of candlelight as copal smoke snakes through the air. His grandfather, Fernando, who had Spanish origins, passed down generational wine and breadmaking traditions. “I remember he had his wood oven and a huge canoe to knead the dough by hand while he smoked his cigar,” Armenghol recalls. “And my grandmother made black mole and pumpkin candy for the season.”

Armenghol’s lens has captured the ceremony of people in Santa Catarina Minas, Ocotlán, who distill mezcal in pots made of clay rather than copper or metal. His images explore the hallucinations that can arise from drinking the ancient spirit. “For a long time, I have photographed all kinds of celebrations for the holiday, and each time I lean more towards intimate moments that contain the idiosyncrasies between Indigenous people and death,” he says. Armenghol seems to be drawn to these “muerte” rituals, for they are a contemplation of the impermanence of life that make the shadowed gnaw of death so mesmerizing.

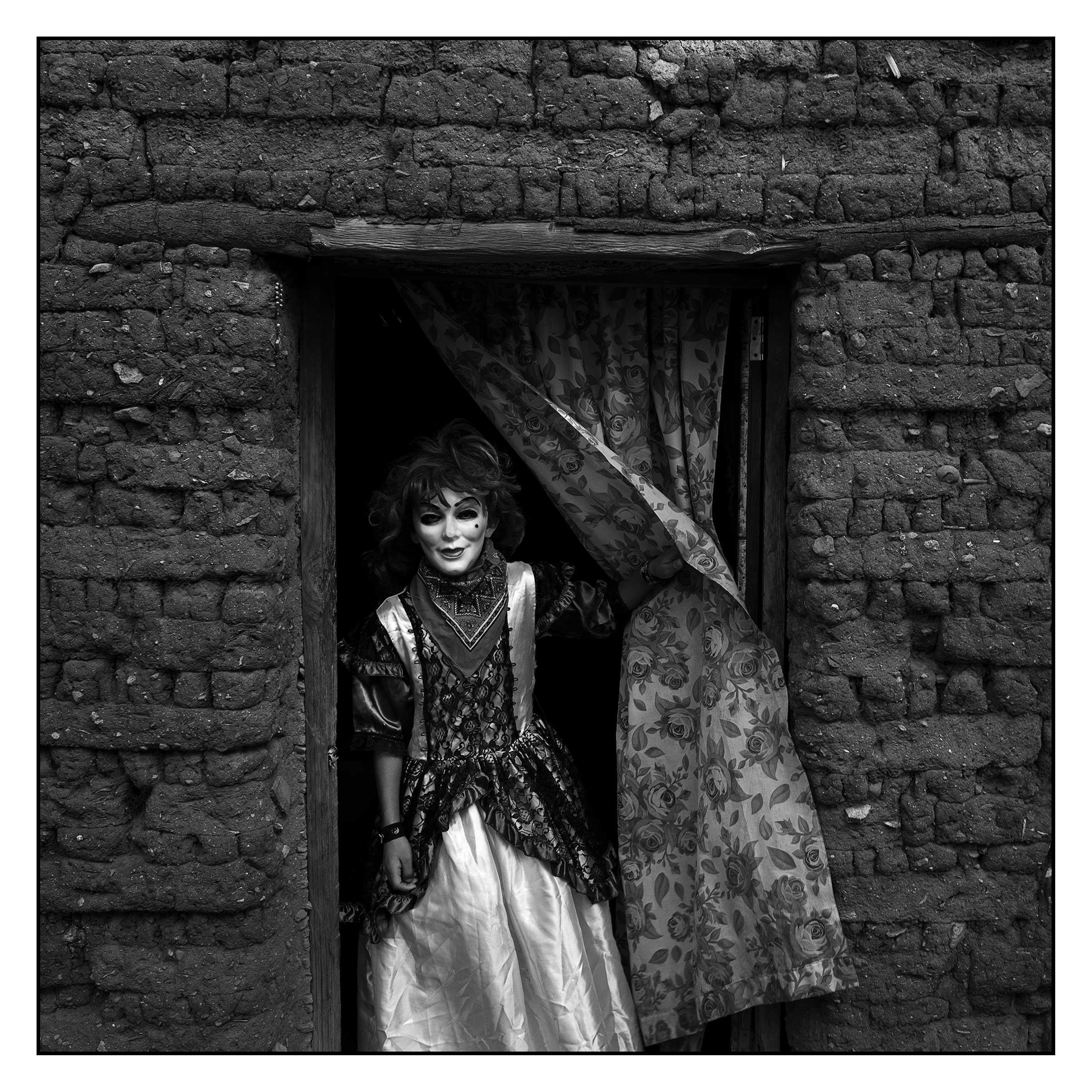

Another ritual central to the holiday involves the entire family, who make their way together to the graves of their ancestors. Armenghol’s images show joyful people in disguise who move through the night, masked characters that fuel the imagination. At dawn, they arrive at the cemetery to sip on mezcal, genuflect, dance, and channel the memory of the deceased. “They wear outfits presentable for death, belonging to a playful world of fantasy—a parody of everyday life,” he explains.

Armenghol, too, with a camera slung over his shoulder, dons a celebratory mask so as not to be seen as a mere mortal. “Thank you life, thank you, Death,” he recites.