Your Body’s Scent Matters More Than You Think

Humans across the globe have linked fragrance to personal hygiene for millennia, but in the West, the obsession with female cleanliness arguably originated with early 20th-century ads selling depilation—or hair-removal—products to women. And the constant bombardment to mask and remove has unforeseen implications for our health and immunology.

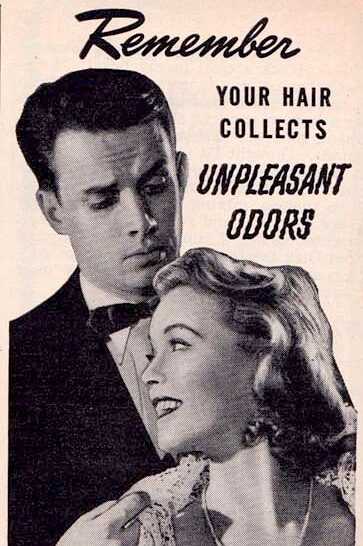

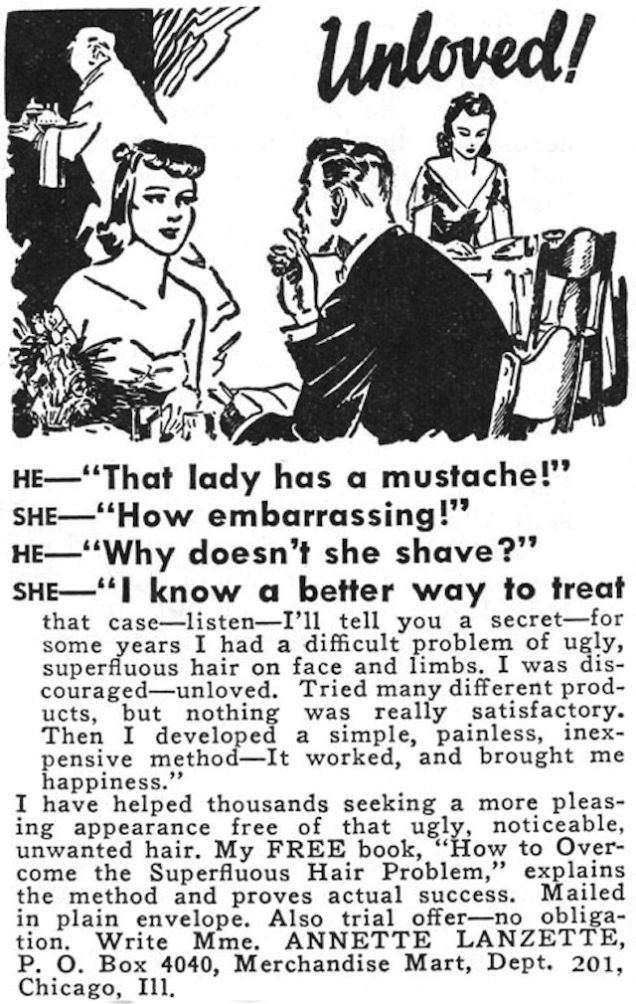

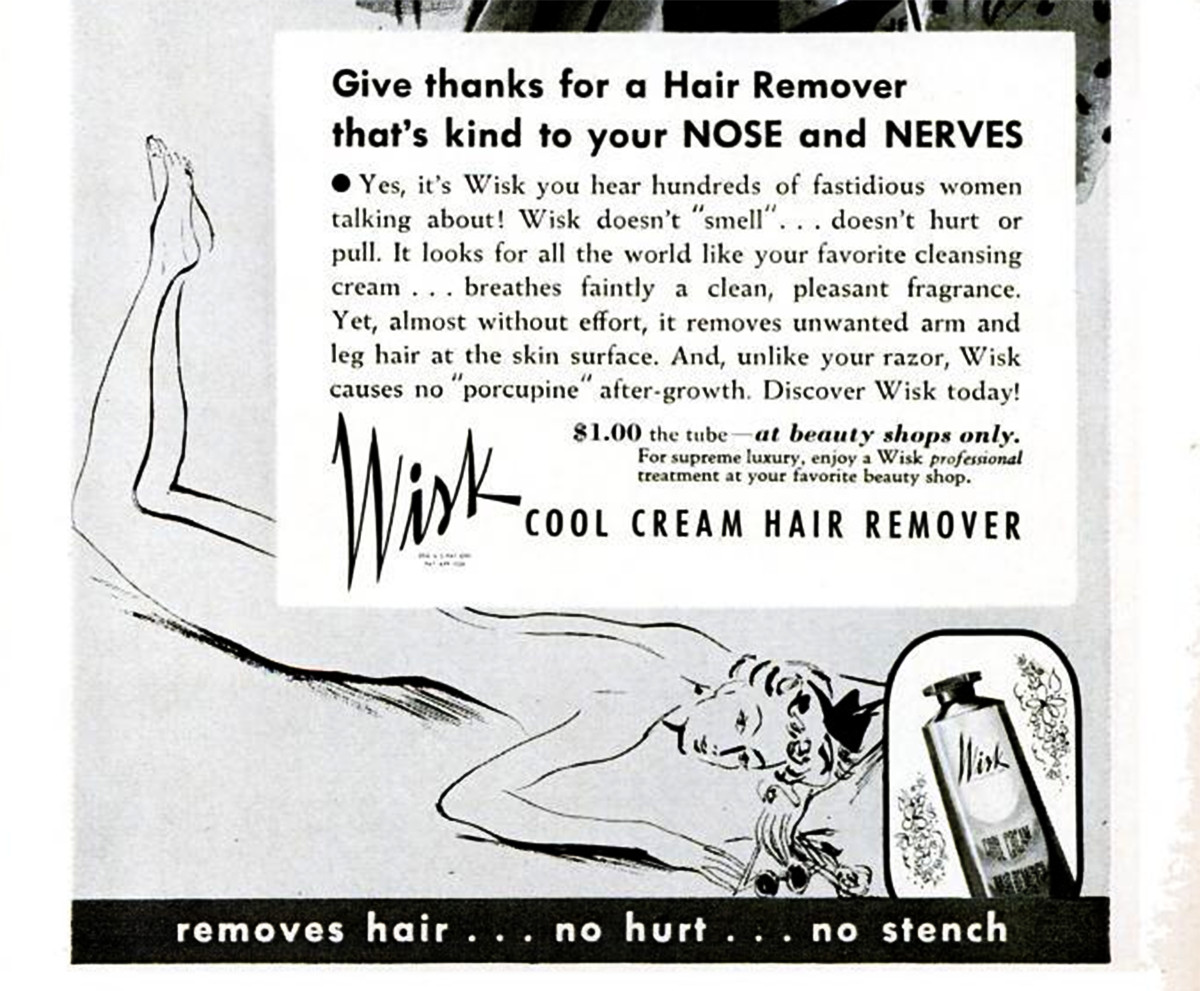

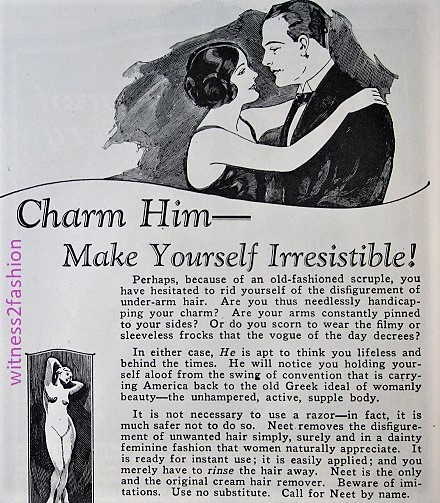

Throughout the 19th century, women—and their partners—were generally indifferent to their body hair. But by the 1920s, women’s clothing had grown more revealing, exposing what the beauty industry called “unsightly,” “embarrassing,” and even “disfiguring” leg and underarm hair. In an effort to sell a range of novel cosmetics, the depilation industry homed in on women’s insecurities—which, at the time, were largely linked to marriage and romantic relationships—equating femininity with a “fastidious” approach to grooming this “unwanted” hair. One ad for Veet from the 1910s proclaimed that “insistent and obvious growths of superfluous hair . . . take away a woman’s charm and rob her of her daintiness,” making her less desirable to prospective husbands. By the 1950s, the messaging was even graver, explicitly deeming women with body hair “unlovable.”

Many of these depilation products were scented, and the crusade against body hair and body odour went hand-in-hand. Another Veet ad declared that “hair under the arms is not only ugly and repulsive-looking, but greatly advocates the old problem of body odour.” Today, deodorant is widely accepted as a necessary step in our morning routine, but like these early hair-removal tools, its prevalence sprang from marketing campaigns that created new problems to sell solutions.

The “feminine hygiene” industry emerged at the same time. Taking the “unlovable” verbiage up a notch, these ads warned that “poor feminine hygiene” would cause friends to gossip and husbands to leave. Lysol—the disinfectant you likely use to clean your kitchen—was touted as a “safe and non-caustic” douching method that “destroy[ed] odor” and [kept] women “glamorous, dainty, and lovely to love.” Even today, drugstore shelves are teeming with scented menstrual products, powders, sprays, and washes, despite extensive research proving that their scent-producing chemicals actually cause harm to vaginal health.

Though the marketing of hygiene products has gradually shifted away from the shocking language of past eras, several brands continue to promise women “odour-free protection” or “a fresh scent.” And this promise is not limited to what we find on pharmacy aisles.

Canadian lingerie company Effleure wants its essential-oil-infused (read: non-toxic) line to make women feel “confident,” “special,” and “empowered” . . . “from the bedroom to the boardroom.” Effleure emphasizes that scented intimates may help women feel more comfortable with themselves—and any romantic benefits are secondary to their own pleasure. Founder Virginia Marcolin even addresses the inherent importance of bodily aroma, insisting that “[Effleure’s] intent is not to mask a woman’s natural scent, but to enhance it.”

“A woman’s natural scent is intoxicating in itself,” she says. “We are just adding a layer of icing on top.”

This is a pretty progressive message. But despite the celebratory approach to female intimacy, it’s tough to separate businesses like Effleure from brands that target women’s self-doubt to market a product. Regardless of intention, it’s a nebulous line: Can scented products uplift women through the instinctual power of fragrance, or do they inevitably perpetuate the idea that our natural scents are somehow shameful?

Let’s examine the instinctual power of fragrance. Olfaction is at the root of so many necessary biological functions, including how we select a partner. Whether you realize it or not, someone’s natural smell may be a huge part of your attraction to them, and vice versa.

In his 2017 paper “Poor human olfaction is a 19th-century myth,” John P. McGann, psychology professor at Rutgers University’s Center for Cognitive Science, cites an earlier study claiming that humans can discern a range of nearly 1 trillion odours (though this metric is contested by other experts). He aims to dispel the myth that humans have a weak sense of smell, emphasizing how important the olfactory sense is to our social interactions. According to McGann, “odor-mediated communication between individuals . . . is now understood to carry information about [our] familial relationships, stress and anxiety levels, and reproductive status.” Body language, then, is about much more than facial expressions, posture, and hand gestures—it’s about the silent messages we send to each other’s noses.

If (pre-COVID) Tinder bios are any indication, people seem to value adventurousness, a love of craft beer, and dog ownership in potential partners—but perhaps more important than all of the above (especially during a pandemic) is immunologic compatibility, the biological impulse to pair up with someone whose immune system differs from yours. Though, admittedly, it doesn’t sound quite as fun as a hike or a night at the brewery.

Merging divergent immune systems is thought to create a stronger mélange of immunity in our offspring, leading to greater resistance against a plethora of pathogens. Some research suggests that immunologic compatibility may also affect emotional and sexual satisfaction in a relationship, even influencing the inclination to have kids in the first place.

How can you tell if you and your partner share this sort of genetic chemistry? For starters, immunologic compatibility is determined in part by olfactory cues—so if you’re intoxicated by the smell of the shirt your boyfriend wore yesterday, your immune codes are likely in sync. (It’s worth noting here that most research investigating the link between olfactory function and sexual behaviour focuses solely on cisgender/heterosexual couples, resulting in limited knowledge about how scent affects attraction for LGBTQ+ folks.)

But what if your partner wears cologne or perfume? Are you actually attracted to that hint of grapefruit or touch of tobacco rather than their body’s natural scents?

The answer is somewhat complex. According to a prominent 2012 study, fragrance and body odour combine to create a third, “individually-specific odor mixture” that is notably distinct from these two components. Still, you can’t separate the parts from the whole. While some people might think they’ve chosen a fragrance to mask their natural aroma, they are subconsciously drawn to scents that complement and even enhance it. This affinity for certain smells is largely based on our own unique immunological profile (though environment may also play a role), which leads us to measure external scents in relation to those of our bodies. So wearing fragrance doesn’t really hide our olfactory signals—it intensifies them, meaning you may think you love your partner’s perfume, but you actually fancy how it accents them.

You need not eschew your favorite perfume to feel empowered in your natural state. With evolving attitudes about gender roles and beauty standards—and the wealth of information at our disposal—true empowerment comes from choices that make you feel fulfilled, from what you buy to what you wear to how you smell. It all comes down to prioritizing your own health and well-being. Now put that in your Tinder bio.

_________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter, here.