Reset

The Paris Opera Ballet documentary debuts in Canada.

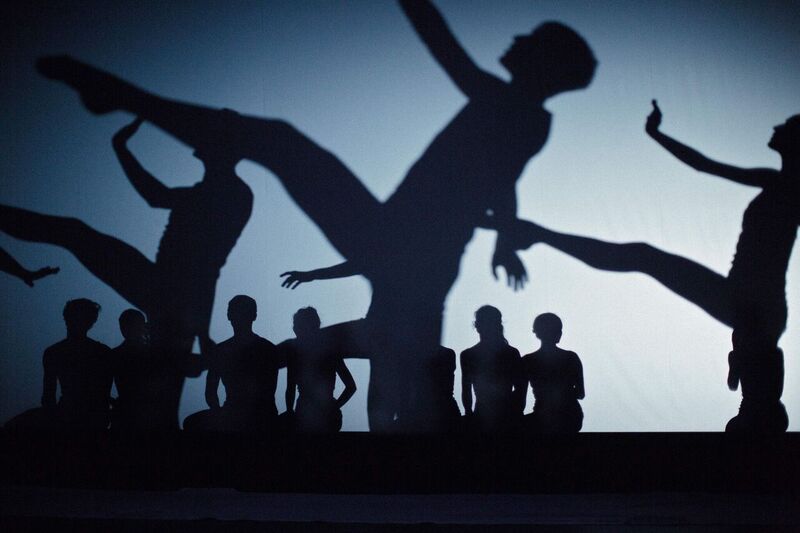

Reset, a must-see dance documentary opening at Toronto’s Hot Docs Ted Rogers Cinema on December 23, 2016, and Vancouver’s Vancity Theater on New Year’s Day 2017, both for two-week runs, highlights the discrepancy between innovation and convention within one of the world’s oldest ballet companies.

The 11th in a series of portrait-like docudramas French film duo Thierry Demaizière and Alban Teurlai have created during 15 years of collaboration, Reset (or Relève as it is called in French) goes behind the scenes at the Paris Opera Ballet to watch Benjamin Millepied plan his inaugural gala for the fabled institution, and, inadvertently, also his own exit from the company he joined as artistic director less than a year earlier.

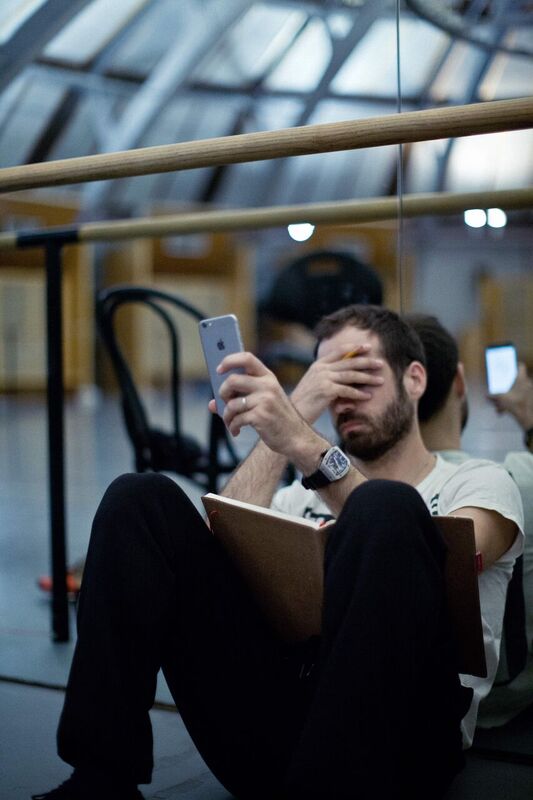

The film is a countdown, literally and figuratively. Starting 39 days before the premiere of a new abstract ballet that Millepied creates before the viewer’s eyes from Nico Muhly’s original electronic and orchestral score and Iris van Herpen’s laser-cut costumes, before abruptly bowing out. “We wanted to tell the story of the creation of a ballet but also to make the spectator understand the almost imperceptible tensions that were growing day by day between Benjamin and the institution,” explains director Demaizière, a former journalist. “We wanted to hint at why he left with the footage that we were able to access.”

That footage is exquisite as well as exploratory. Teurlai’s roving camera takes in dance and dancers along with the legendary theatre itself, granting the viewer rare insights into the artistic process and the arcane world of the Paris Opera, where classical dance as we know it originated around 350 years ago. Millepied states that on one hand, he wants to pay homage to centuries of deeply entrenched tradition that has helped make the French ballet world renown. “This company,” he says in a voice-over, “was reputed for its phrasing, for the way dancers moved. This is sorely missing from the school today.”

On the other hand, the maverick choreographer and visionary wants to shake things up, and states at the start that he will cast from the corps de ballets, instead of using soloists or principal dancers as would normally be the case for a new creation. Millepied also says he wants the cast to be multiracial, another radical departure from protocol. The Paris Opera, for those who might not know, is the birthplace of the ballet blanc, a trope that continues to dominate classical dance today. Millepied sees all those white swans as a manifestation of latent racism. His goal is to pluck out the offending mindset and make ballet more inclusive. “How will new people come to the ballet if they can’t identify with the dancers?” Millepied asks out loud. “If art can’t be an example for society, where are we heading?” These are fighting words, endearing Millepied to a contemporary audience but also having the potential to alienate him from the status quo. It’s a delicate balancing act, and one that Millepied can’t quite pull off—but not for lack of trying.

A former New York City Ballet principal dancer more widely known as the choreographer of Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan who married the film’s star, Natalie Portman, Millepied is a true mover and shaker, an innovator with the potential to push classical dance forward into a bold new future. But the Paris Opera, a hierarchical organization heavy with tradition, ends up being a less than malleable partner. “It is sometimes hard for major companies aides to move forward,” says Paris Opera director Stephane Lissner early in the film, underscoring the underlying problem. Just five months after his 11-minute gala ballet—the symbolically titled Clear, Loud, Bright, Forward—debuted at the fabled Palais Garnier in Paris on September 25, 2015, Millepied abruptly resigned from the ballet company’s top job. What happened?

The filmmakers don’t exactly say—and neither does Millepied. Since returning to the U.S. with his Hollywood movie star wife to take over directorship of the more experimental L. A. Dance Project, he has refused all interview requests. Like the dance it so faithfully follows, Reset—the word means restoring something back to its original position—suggests, more than states, a likely scenario.

Says Demaizière, “Benjamin Millepied quit five months after we finished filming, so by the time the film was released we were no longer breaking news. So we therefore decided to announce Benjamin’s departure using a simple caption at the end of the film. A painstaking explanation of the reasons he’d chosen to leave would have been too complicated, and to tell the truth, we don’t really know exactly what happened between Benjamin and the directors of the Ballet. We were very privileged witnesses of his short stint at the Opera Ballet. The film is there to show what we saw, and nothing more.”

Photos courtesy of KinoSmith.

_________

Never miss a story, sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter, here.