Moving Still: Performative Photography in India at the Vancouver Art Gallery

An exhibition of three generations in Indian photography.

A photograph cannot lie; it captures the reality of time in a single frame. And yet, through the imaginative art of performance photography—the act of telling stories through visual stills—reality can be skewed by the manipulation of subject and photographer. The invention of the camera sparked the ingenuity of artists in India to experiment with this notion of skewed reality by combining the photographic form with performance art.

The Vancouver Art Gallery’s (VAG) recently opened exhibition Moving Still: Performative Photography in India traces the trajectory of the art form in India from the early 1800s up to the present day. Displaying over 100 works by 13 India-based photographers, themes of gender, religion, and sexual identity are contemplated through the stillness of photographs.

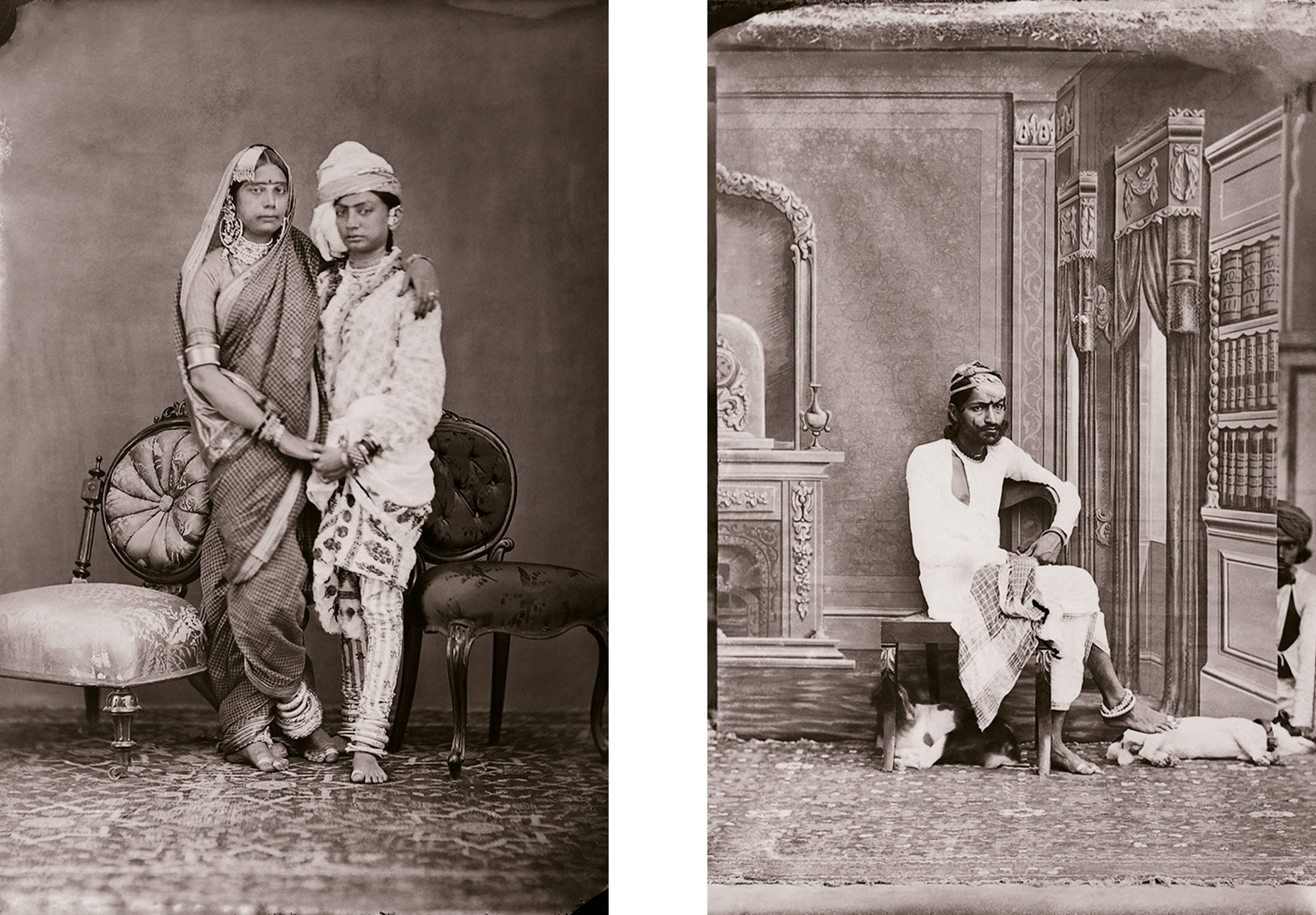

On the third floor of the VAG, the exhibition opens with personal photographs by Maharaja Sawai Ram Singh II, dubbed the “photographer prince”, of what is currently Jaipur, Rajasthan. Ram Singh’s self-portraits and photos of the royal palace offer a view of Indian life through a royal lens. Perhaps his most famous photographs are a progressive observation on gender and class identity in one of Jaipur’s zenanas―an Indian term for the female quarters of dancers and musicians. “This is the first documentation in South Asia of women performers and entertainers,” says Gayatri Sinha, guest curator of the exhibition. “In a sense, he empowers this entire sorority of women.” Moving Still marks the first time Ram Singh’s photographs have been exhibited outside of India.

Maharaja Sawai Ram Singh II, Unidentified women of the zenana, c. 1870 digital print from an original wet collodion glass plate negative, Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II Museum Trust (left); Maharaja Sawai Ram Singh II, Self-portrait with dogs, c. 1870 digital print from an original wet collodion glass plate negative, Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II Museum Trust (right)

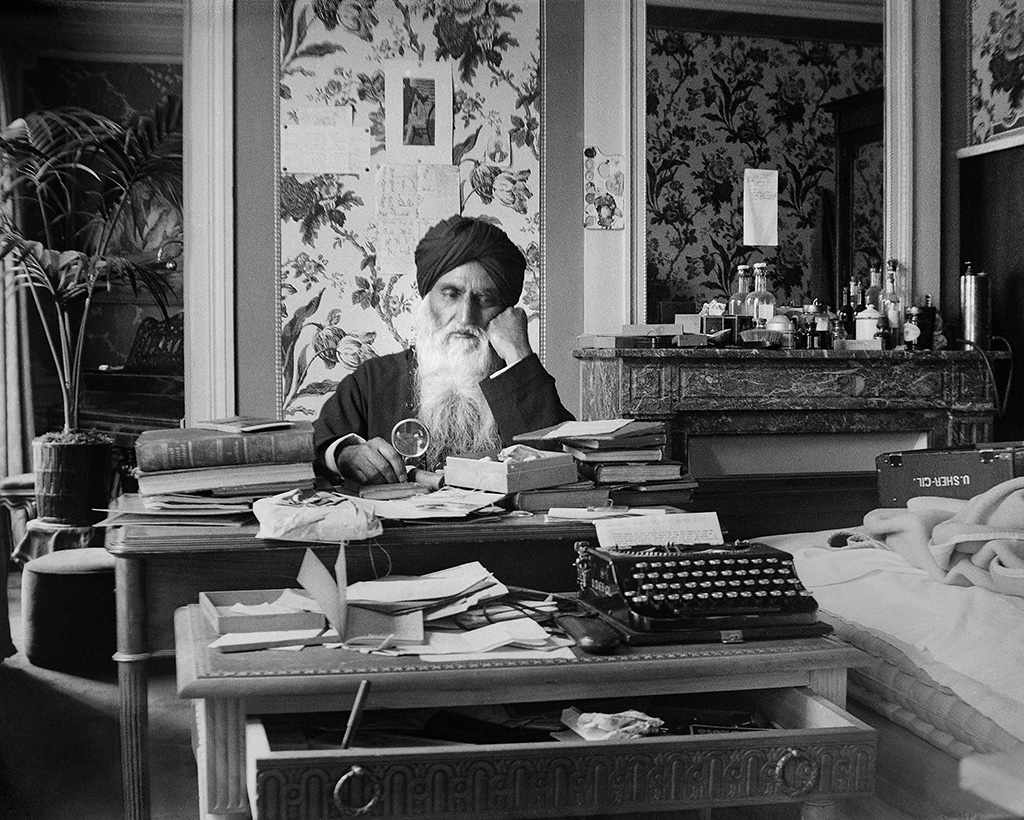

Also showcased is another pioneer of Indian photography, Umrao Singh Sher-Gil, a Sikh aristocrat also known for his female-centred photography. Sher-Gil focused on the women within his own family, his two daughters, Indira and Amrita (one of India’s pioneers in modernist art), along with his wife, Marie-Antoinette Gottesmann Baktay, a Hungarian opera singer. Sher-Gil’s family portraits are intimate renditions of a Hungarian-Indian household, made even more poignant by the premature deaths of Amrita and Marie-Antoinette. Later photographs by Sher-Gil are self-portraits of isolation in his study, surrounded by books, forming a sense of self-fashioning new to India at the time.

Umrao Singh Sher-Gil, At his study table: self-portrait, c. 1933, modern silver gelatin print with selenium toning. Courtesy of PHOTOINK

Umrao Singh Sher-Gil, Sisters in bed, c. 1932, modern silver gelatin print with selenium toning. Courtesy of PHOTOINK

Moving on to the contemporary, the exhibition becomes more experimental and challenging of societal norms. Naveen Kishore’s photo stills from his video Performing the Goddess: The Chapal Bhaduri Story follows Chapal Bhaduri, an actor famous for being a female impersonator in folk theatre when women weren’t allowed on stage. Bhaduri’s transformation into a female goddess, portrayed through a series of still images, is a performance of homosexual desire encoded into ritual practice. “The gender swap allows a type of freedom to the artist,” says Sinha, referring to both Bhaduri and Anita Dube, who impersonates a Muslim man speaking to the rise of India’s right in one of the few video performances of the exhibition.

Naveen Kishore, Performing the Goddess–The Chapal Bhaduri Story, 1999 inkjet print. Courtesy of the artist

Naveen Kishore, Performing the Goddess–The Chapal Bhaduri Story, 1999 inkjet print. Courtesy of the artist

One of the most modern installations is Gauri Gill’s 2015 portrait series Acts of Appearance, which touches on the everyday life of the socially and economically powerless in India. Artists of a Maharashtra village were commissioned to create and wear papier mâché masks emblematic of their own identity and pose as subjects for Gill. In the series, she imbues a strong individualistic identity with the traditional artisan craft of papier mâché, a form typically meant to create religious deity masks in Hinduism.

Gauri Gill, Untitled from Acts of Appearance series, 2015–ongoing, archival pigment print. Courtesy of the artist

Pushpamala N’s conceptual photography is the highlight of the exhibition. Often playing the characters in her own photos, Pushpamala centres herself in photo romances, a term she uses to describe the romantic nature of her performance photographs, such as in the hand-painted photo series Sunhere Sapne (Golden Dreams) in which she plays both a sixties-era stereotypical middle-class Indian housewife and her alter-ego, a Bond-like wealthy socialite. Despite the dreamlike, nostalgic elements of her photographs, Pushpamala assures, “Nothing is nostalgic, it’s to do with the present.” The subliminal references of Indian nationalism, Bollywood cinema, and South Indian culture in Pushpamala’s work offer a sort of inside joke to South Asian audiences, but allude to the tropes recognized in Western culture too. “It’s tongue-in-cheek,” says the artist.

Sunhere Sapne (Golden Dreams), 1998 hand-tinted black and white photograph, Shumita and Arani Bose Collection, NY (left); Sunhere Sapne (Golden Dreams), 1998 hand-tinted black and white photograph, Shumita and Arani Bose Collection, NY (right)

Moving Still: Performative Photography in India is on at the Vancouver Art Gallery until September 2, 2019.

_________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter here.