Chan Hon Goh

Dance like everyone is watching.

On stage, Chan Hon Goh is the quintessential ballerina. A principal dancer with the National Ballet of Canada, Goh, 35, is one of the company’s most exquisite classicists. Her ballon, or the lightness of her landings, is legendary. Her every movement is filled with a lyrical grace that defies gravity, and the dramatic power of her expressive body compels attention. The great American Balanchine ballerina, Suzanna Farrell, describes Goh as someone who “illuminates technique”. In short, Goh is everything that makes the ballet beautiful. She transforms the challenges of dance into smoke and mirrors; we see only the elegance, none of the struggles.

She puts together international ballet galas to great acclaim, choosing the dancers from among the world’s best, and her producing credits include a superstar tour of China, and glittering programs for Festival des Arts de St-Sauveur in Quebec, and London, Ontario’s Grand Theatre. She has her own line of pointe shoes with average annual sales of 10,000, and an upward growth curve. Her autobiography for Young Readers, Beyond the Dance: A Ballerina’s Life, written with Cary Fagan, has been short-listed for The Norma Fleck Award for Children’s Non-Fiction because of its positive message about the immigrant experience. Not surprisingly, one of Goh’s heroes is superstar Mikhail Baryshnikov. “I believe in being multi-faceted,” she says, “because it makes you a better dancer. I also am realistic that dancers have short careers, so it’s smart to look for other outlets that will guarantee financial security. Baryshnikov has his own dancewear and he’s also into acting. The difference is, people go to him with ideas, while I start my own projects.”

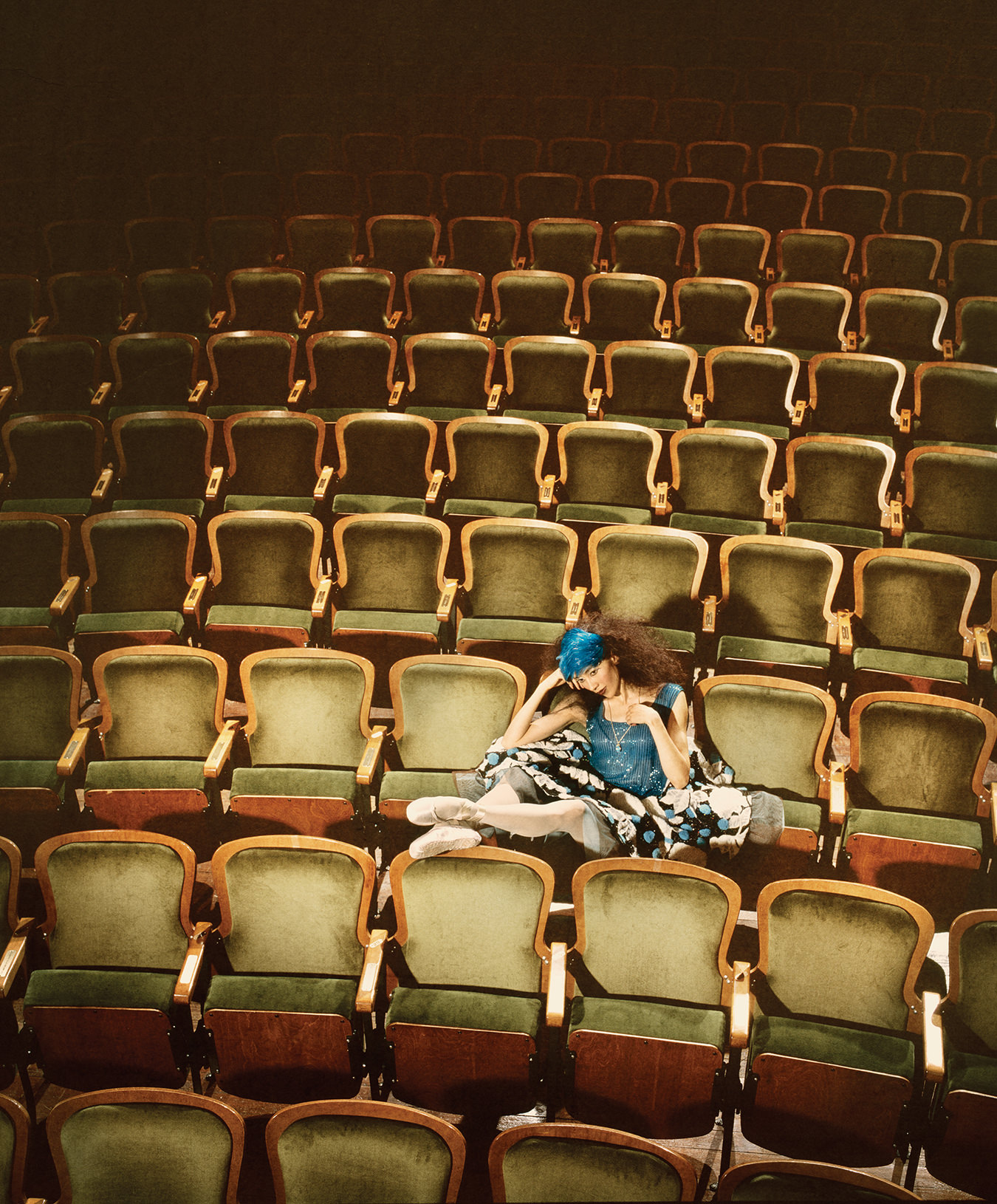

Goh wears Ashish of London beaded turquoise skating dress and Ashish cream flower lace skirt with brown hologram. Wolford stockings Fatal 15 in Marmor ($60). Lilliput Julietta Cap. Shoes: Principal by Chan Hon Goh diamond pointe shoes. Jewellery: Schlumberger Turquoise Egg with 18-karat gold chain, available at Tiffany & Co.

Goh is proof that dance just might be genetic. Both her mother, Choo Chiat Goh, and father, Lin Yee Goh, were principal dancers with Beijing’s prestigious National Ballet of China, before immigrating to Vancouver when Goh was seven. She is the niece of the late, great American choreographer, Choo San Goh. In fact, out of her father’s family of ten siblings, five have had careers in dance. Nonetheless, although her parents founded the famed Goh Academy, one of Canada’s most lauded ballet schools, they never saw their only daughter as a dancer. With her long, flexible fingers and innate musicality, they envisioned Goh as a concert pianist, and she studied piano from age three to fourteen. “The general consensus was I didn’t have the right physicality,” says Goh. “I had no natural turn-out, and my coordination and suppleness were poor. I had to work really hard to put all these things into my body.”

As she pined away on the sidelines watching rehearsals and classes, Goh dreamed of being onstage. “I always saw myself as a ballerina, alone in the spotlight,” she says, “even when no one else did. I was forever trying on my mother’s pointe shoes, and dancing to music on the TV or radio.” Because her parents were so busy, her aunt, Soo Nee Goh-Lee, helped to look after her. When Goh was nine, Goh-Lee put her niece in a ballet class that she taught at the Vancouver Academy of Music, her aim being for Goh to acquire posture and discipline while keeping occupied after school. Goh’s big break, as she calls it, came when her parents began a children’s division at their own studio, and Goh began taking classes there. The legendary British dancer/choreographer, Anton Dolin, who knew her parents, dropped by the school when he was passing through Vancouver, and surprised everyone by singling out Goh as having the best potential in the class. “It certainly made my dad more interested in me,” she says, “but if I’m headstrong today, it’s because all my life, I’ve had to fight other people’s doubts, and prove myself over and over again.”

Goh wears Ashish of London beaded turquoise skating dress and Ashish cream flower lace skirt with brown hologram. Wolford stockings Fatal 15 in Marmor ($60). Lilliput Julietta Cap. Shoes: Principal by Chan Hon Goh diamond pointe shoes. Jewellery: Schlumberger Turquoise Egg with 18-karat gold chain, available at Tiffany & Co.

When she was 16, Goh, at her own insistence, entered the Prix de Lausanne, the most important competition in the world for dancers under 18, and won the grand prize, beating out a field that included Darcey Bussell, Julie Kent and Kaori Nakamura, who would go on to greater glory at the Royal Ballet, American Ballet Theatre, and Pacific Northwest Ballet respectively. Companies came calling, but it was James Kudelka who suggested Goh explore the National Ballet. The two met when Kudelka was a judge on a Canada Council audition panel, and Goh had applied for a study and travel grant. “Chan was amazingly evolved as a classicist, which put her in a niche by herself,” explains Kudelka. “I was happy when I heard that Reid Anderson had persuaded her father to let her join the company.” At 18, the very gifted Goh was in the corps de ballet of the National, and a principal dancer six years later.

Goh is married to Chun Che who is twenty years her senior. Her husband, also a former principal dancer with the National Ballet of China, had been a student of her father’s in Beijing. The senior Goh invited Che to come to Canada as a student when he expressed interest in experiencing a wider variety of repertoire. A very talented dancer, Che’s career came to an abrupt halt in 1987 when a car making a left hand turn rammed into his at an intersection. He had already been moving into teaching and choreography, but the accident, which left him with disc and spinal injuries, put him permanently into the studio. That was where the teenage ballerina wannabe first had a crush on the stern taskmaster who was always giving her corrections. Just before the car accident, Che choreographed a romantic pas de deux for himself and Goh for a ballet gala, and it was during the rehearsals for The Butterfly Lovers that she fell in love. Che also choreographed her Prix de Lausanne solo that won her the top prize. They began to go together when Goh was 16, and married when she was 28.

When Goh joined the National, Che followed her to Toronto. He is now head of ballet at George Brown College’s dance department, and also teaches company class for Ballet Jorgen. Che, who doesn’t look his 55 years, confesses that he is embarrassed by the age difference for Goh’s sake, but Goh speculates that if her significant other had been a dance peer, and equally ambitious, her own career might have faltered. In Che she has found nothing but unbridled, unselfish support. In fact, Principal Shoes, which the couple launched in 1998, came about as a result of Goh’s desire for a project that they could share together.

Goh wears Louis Vuitton satin blouse with ascot collar and black tulle and Louis Vuitton satin skirt with taffeta overlay. Wolford stockings Fatal 15 in Marmor. Lilliput large feathered headpiece. Jewellery: Yellow sapphire ring 24. 88 carats surrounded by 44 diamonds in platinum with pear and baguette diamond earrings, both available at Birks.

Che designs the pointe shoes, ballet slippers and dance boots, working with a production partner in China, while Goh handles the marketing. Principal shoes retail for $70 Canadian which make them very competitive. “Our mandate,” says Goh, moving into sales rep gear, “is to develop a longer-lasting, affordable, hand-made shoe, without New Age material, that provides the maximum balance, support and weight distribution for a dancer’s needs in both training and performance. Dancers, including my husband and myself, always complain about shoes, and we felt we could come up with something better based on our own experience.” Wherever Goh performs, she takes Principal shoes along, and in her off time, becomes a company shill. “Being who I am gets me in the door,” she says, “but the shoes sell themselves.” One of Principal’s first customers was Kudelka who commissioned the fledgling company to construct the men’s boots for his new Swan Lake in 1999.

Not only has she added dance retail conventions to her to-do list, she is also a much-in-demand guest artist all over the world, most notably, for the last three years with Suzanne Farrell Ballet that mounts highly acclaimed Balanchine evenings throughout the United States. Goh also gives master classes and intensives when she can fit them in, and is a frequent public speaker for various Chinese professional and cultural groups. As an example of her frenetic itinerary, between September and December, 2003, she rehearsed with Farrell in New York, performed in the National’s Western Canada tour, danced with Farrell in Princeton, New Jersey, flew to Singapore as a guest artist, came back to Toronto to rehearse Onegin with the National, toured with Farrell to Detroit and Michigan, came back to Toronto for more rehearsals, followed by more Farrell performances up and down California, which segued into the National’s fall season and performances at Washington, DC’s Kennedy Centre with Farrell, ending the year with Nutcrackers for both the National and California’s Riverside Ballet.

Goh does worry that she drives herself too hard. “When I clear everything off my list, I feel the immediate need to refill the docket,” she says. “In the back of my mind, I think I might enjoy being a housewife. I can’t iron, but I’m a good cook when I want to be. Whenever I fantasize about this, my husband just shakes his head in disbelief.” The down side of always pushing herself to perfection is dance injuries, and Goh has had her fair share—three punishing stress fractures and a painful bout of Achilles tendonitis. “I know I shouldn’t dance in pain,” she adds, “but I feel like such a wimp if I give in. It’s like the end of the world if I can’t dance, and no dancer ever wants to pass up an important engagement. I never feel the pain when I’m on stage because of the rush that comes from performing.”

Goh wears Arthur Mendonça green chiffon dress. Lilliput silk and velvet cocktail hat. Wolford stockings Fatal 15 in Marmor. Jewellery: Schlumberger 18-karat gold and pearl “Pea Pod” brooch available at Tiffany & Co. Shoes: Principal by Chan Hon Goh diamond pointe shoes.

In 2002, Goh suffered a miscarriage at two and a half months, and she admits that she made herself even more busy to cope with the loss. “It’s the hardest thing that a woman endures,” she says. “I know that many first pregnancies end that way, but it’s cruel that you make plans, and it’s over before it’s even started. I think in my subconscious, I knew I was too happy, and that I was afraid I was going to lose the baby—and then, like a self-fulfilling prophecy, I did.” Goh and Che do plan to try again for children sometime in the future.

The ballerina, nonetheless, feels that her passion for dance has grown stronger because she has so much on her plate. “Not to sound corny,” she says, “but the tedious details of planning galas and tours, or running and marketing a company, makes me pine for the stage. Compared to sitting in front of a computer screen, or hustling a room full of people, there’s no contest. On the other hand, my non-stage life has put me in touch with the real world, and I realize I’m a very responsible person who always delivers on my commitments.” As ballerina-cum-entrepreneur, Goh is also savvy enough to hire her own PR person to keep her name in the public eye. Says Goh: “It’s important that people learn about me as a person, and as an artist—especially since I have a life off-stage.”

When asked what a post-dance future holds, Goh takes a pragmatic view. “I want to be in a position where I will have a real impact,” she says. “Being a teacher or a coach doesn’t appeal to me. I want to be able to use my years of dancing and my knowledge of the dance community in a very substantial way.” When asked whether she sees herself as an artistic director down the line, Goh replies with a Cheshire Cat smile: “In order to run a company, you need business and organizational skills, and mine are developing very nicely.”

Goh wears Louis Vuitton satin blouse with ascot collar and black tulle and Louis Vuitton satin skirt with taffeta overlay. Wolford stockings Fatal 15 in Marmor. Lilliput large feathered headpiece. Jewellery: Yellow sapphire ring 24. 88 carats surrounded by 44 diamonds in platinum with pear and baguette diamond earrings, both available at Birks.

Fashion Direction and Styling: Anya Shor and Luisa Rino. Make-up/Hair: Jackie Shawn www.jackieshawn.com is represented by the Plutino Group. Production: Stephanie Saunders. A special thanks to Arnie Lappin of the Elgin Winter Gardens for his help with this shoot. All make-up by Guerlain: Eyes: Divinora Eyeshadow in Rose Metal No. 81 and Divinora Lengthening and Curling Mascara in Noir Divin. Cheeks: Divinora Radiant Blush in Rose Plein Vent No. 225. Face: Météorites Powder for the face and Divinora Ultra Smooth Sculpting Foundation with SPF 15 in Beige Clair No. 522. Lips: Divinora Lipstick Colour and Shine No. 264, Divinora Sheer and Shine Transparent Brilliant SPF 10 and Divinora Lipliner in Prune Intense No. 61.

_________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter, here.