-

Photo via Flickr, Raul Lieberwirth.

-

Photo courtesy of Graham’s.

-

Photo courtesy of Graham’s.

-

Photo courtesy of Graham’s.

-

Photo courtesy of Graham’s.

-

Photo courtesy of Graham’s.

-

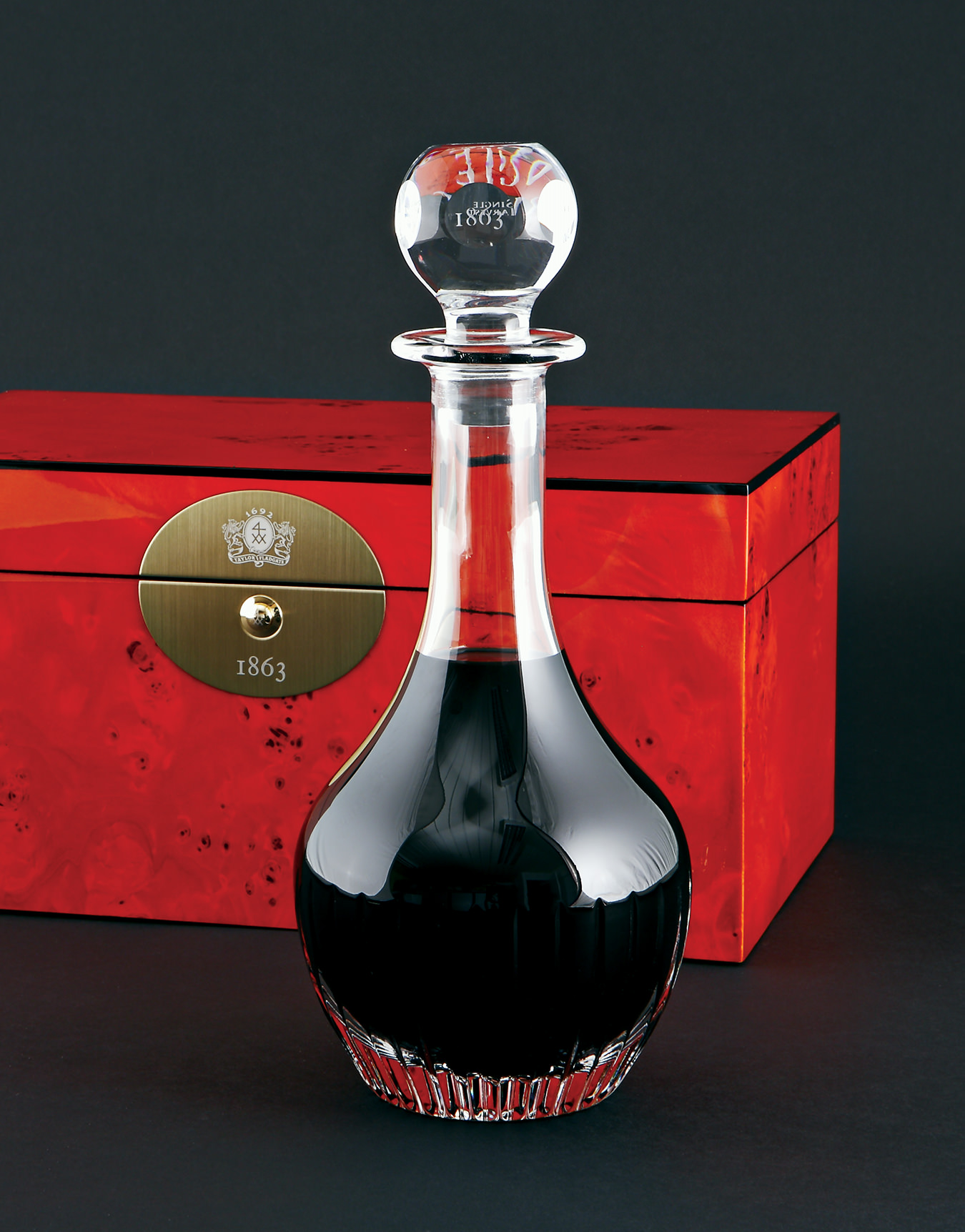

Photo courtesy of Taylor’s.

-

Photo courtesy of Taylor’s.

-

Photo courtesy of Taylor’s.

Portugal’s Douro Valley

A guide to port and Porto.

In the old days, when the Marquis of Pombal ruled Portugal and ox carts, human hands, and little river boats called rabelos were the only way to transport port wine to market, the Portuguese devised a way to measure their precious cargo. Each barrel was presumed to contain a pipe (550L) or as much as an ox could carry on a cart. Only usually, there’s a bit more port per barrel, so to be more specific, additional wine could be measured in almudes (25L)—the amount a woman could carry on her head. If you wanted to get more precise still, the smallest unit was equal to the amount a man could drink in a single day—this was called a “canada”.

Today, if you journey to the “caves” owned by Taylor Fladgate, in the Vila Nova de Gaia neighborhood in Porto, you too can learn about canadas. (Loosely, this word is Portuguese for “it’s no good,” and has led to a persistent if sadly inaccurate legend about how explorers named a certain ice-covered land they came across.) These cavernous warehouses built into the steep banks of the Douro River hold hundreds of barrels of aging port, each stamped with an X with two numbers within it. The upper number is the amount of almudes more than a pipe that lies within; the lower, the canadas beyond that.

Of course, you’ll see a lot more than this. Portugal as a whole is enjoying a hot tourist moment, with food critics and travel writers, families, foodies, and spring breakers the world over pouring into the restaurants of Lisbon, the beaches of the Algarve, the mountains of the far north—and Porto, wine capital and namesake of the country.

It’s here, in Vila Nova de Gaia, that a pre-Roman settlement named Cale could be found, which prospered so under Roman rule that it needed a port—in Latin portus, across the river: the Portus cale. From whence, Portugal, as well as Porto. (Centuries later, British traders would hear the Portuguese o porto, or “the port”, and erroneously call the city Oporto, a name which persists.)

Modern Porto is built on the wine trade, tourism, and an industrialized modern zone to the north and east of the old town centre. It boasts a massive Gothic cathedral, six stunning bridges, and traditional azuleja (or blue-tile)-covered churches, as well as a burgeoning restaurant scene and a spate of new restaurants. But at the heart of it all is port wine.

I beg you to indulge me: if you have tried some of the terrible rotgut that is often marketed as ruby port, particularly from non-Portuguese suppliers, you may be rolling your eyes at the idea of crossing an ocean to get more. This would be as foolish as refusing to visit Bordeaux because you once had some bad Franzia.

The refined 10, 20, 30, or 40-year tawnies and the prized vintage-year ports are some of the greatest achievements of wine-craft. While port is at heart a dessert drink, these are often considerably less sweet than their more popular, lowbrow ruby cousins. Some Portuguese ports these days look beyond dessert as well: in Porto you’ll find white and rosé ports served chilled as apéritifs or even mixed into porto tonico, a smoother variant on the gin and tonic.

The beating heart of the city pumps port, not blood.

There are over a dozen traditional lodges in Gaia, most of which have now been amalgamated into a fistful of larger conglomerates. But one stands above the rest for the effort it has recently been pouring into promoting the tourist industry. As it happens, it’s also (with one possible rival) the purveyor of by far the best ports: Taylor’s, also known in the U.S. as Taylor Fladgate, the lodge where I discovered the other meaning of canada.

In the port industry, wine from various vineyards is spiked with neutral grain spirit while fermenting and then mixed expertly to produce blends, meaning that the port lodge is (with limited exceptions) much more important than the vineyard in determining the quality of the port.

That also means the lodge is the logical centre of tourism, just as you’d be better off visiting a whisky distillery than a wheat field (though the vines up in the Douro Valley are lovely). A few years ago, Taylor’s redid the lodge from top to bottom, abandoning the standard guided tour offered by most port houses in favour of a museum approach. Inside, you’ll find everything from Napoleon’s writing desk (lost on his ill-fated invasion of Portugal) to a split-apart, walk-in port vat. Emerging again into the sun beyond the lodge’s white terra cotta walls, you can take your port tasting in a garden overlooking Vila Nova de Gaia, the Douro, and central Porto beyond. Peacocks and Chinese hens roam before you in what was once the lodge master’s garden.

Next door, they’ve set up the Yeatman Hotel. A feat of marketing as well as planning, it brings together wine and port companies from all over Portugal to offer a hotel that celebrates grapes: each room is dedicated to a different type of wine (and overlooks the Douro in terraced fashion), while the two-Michelin starred Gastronomic Restaurant and its junior cousin the Orangerie offer perfectly paired foods, and even the pool is shaped like a decanter.

From the pool terrace, you can look across the valley that splits Vila Nova de Gaia to the chief rival of Taylor’s: Graham’s. Graham’s has taken nearly the opposite approach as Taylor’s, emphasizing its deep family roots—it’s still owned by a centuries-old port dynasty today. Its book-and-leather-lined Private Vintage tasting room, available on tours for an extra fee, is probably the finest in the city, and its quieter, more traditional lodge is worth the trek regardless.

Meanwhile in the centre of town, new, hip restaurants have spread thickly in the area between the cathedral, the Torre dos Clérigos, and the Caia dae Ribeiera (don’t eat there on the waterfront itself though—nothing but tourist traps), particularly on Rua das Flores and the Rua de Trás. On the former, Brooklyn-style Cantina 32 and more traditionally-influenced Traça are the standouts; try the Francesinha (a traditional sandwich of Porto with cured meats under a bun, covered with melted cheese and tomato sauce) at the latter, and the venison at the former. On the Rua de Trás, petiscos, Portugual’s version of tapas rules. Trasca is definitely a standout—the octopus carpaccio, with a touch of paprika, is the finest version of that dish I’ve ever had. But this superb meal had an interesting hitch: the cheese board was served with saltines. Something small, perhaps, but it encapsulated a larger trend.

This is Porto, to my mind: the kind of place where an amazing experience is right around the corner, but the edges haven’t yet become sanded down. Another way to put it is that one day you’ll hear people talk about Porto before it was overrun by tourists; if you go there today, you can live that “back in the day”, now—for better or worse.

But Vila Nova de Gaia, on the other hand, has been setting the class of the world since the 18th century, and is able to stand tall with the best tourist locations now. The beating heart of the city pumps port, not blood.

_________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter.