-

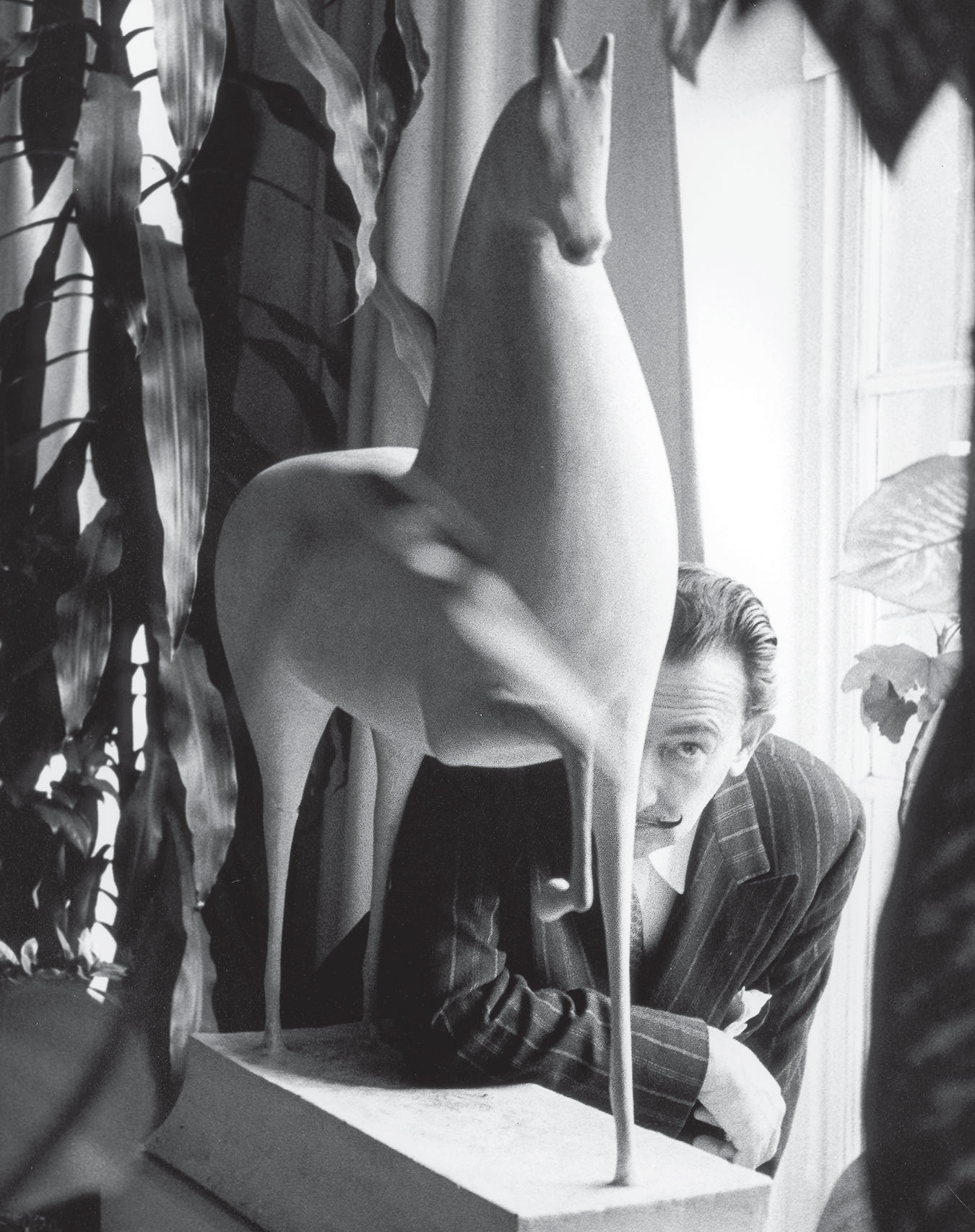

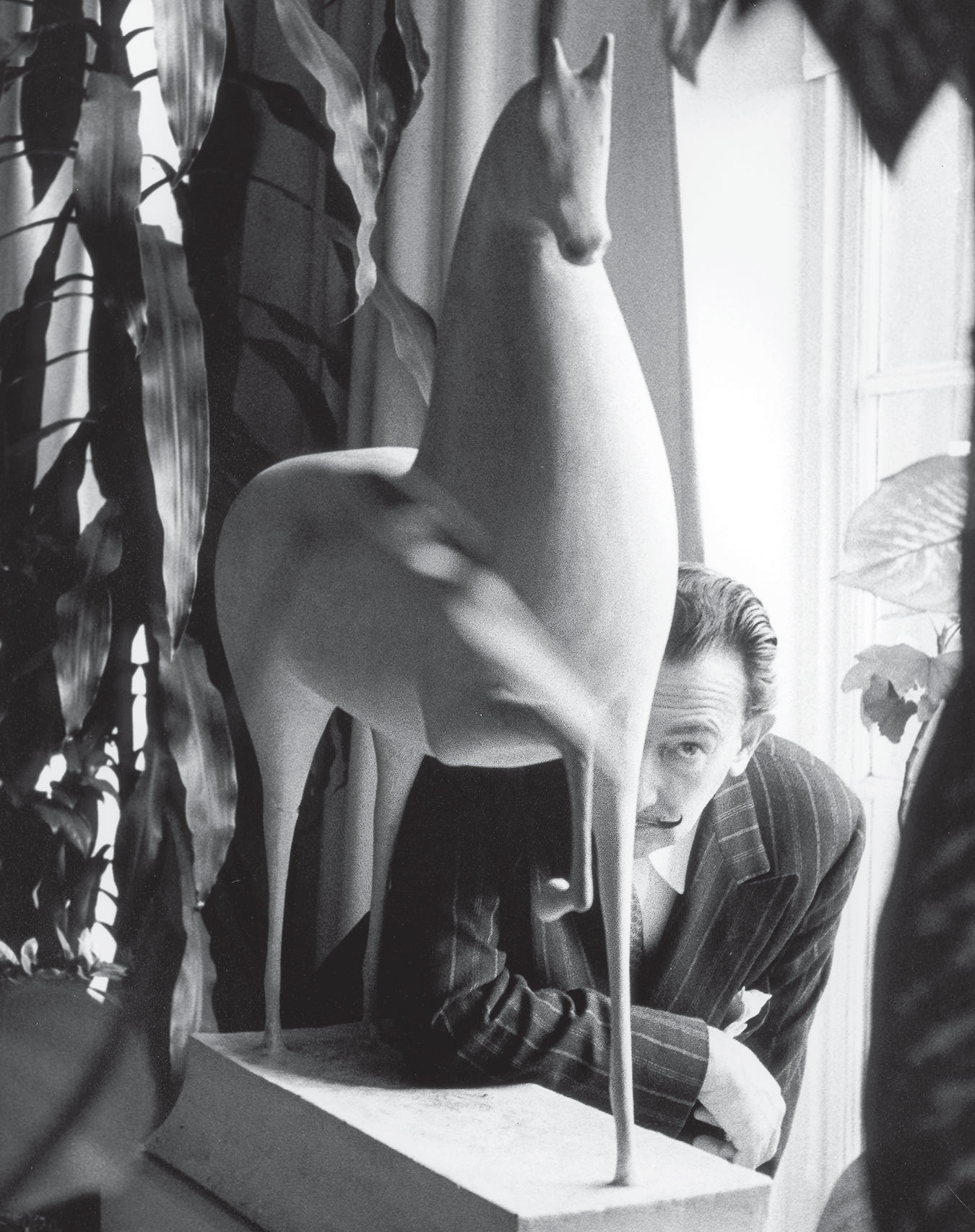

Photo of Salvador Dali being unusually shy. Photo taken in 1958. Photo: Snowdown/Camera Press/Ponapresse.

-

Detail of The Madonna of Port Lligat (first version), 1949, Milwaukee, Marquette University, The Patrick and Beatrice Haggerty Museum of Art.

-

Detail of Premature Ossification of a Railway Station, 1930, Private Collection.

-

Figure at a Window, 1925, Madrid, Museo Nacional Centro De Arte Reina Sofia.

-

Corpus Hypercubus (Crucifixion), 1954, New York, the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

-

My Wife, Nude, Contemplating her own Flesh Becoming Stairs, Three Vertebrae of a Column, Sky and Architecture, 1945, Private Collection c/o the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Salvador Dalí in Philly

Dalí-ance.

The conundrum with writing about a figure like Salvador Dalí is how to encapsulate any sense of his impact, life, influences, theories, accomplishments (and disasters) in the word count you’ve been allotted. The actual number becomes a bit irrelevant because in the end, it’s never ever enough. So, when there are too many places to begin, begin with his work and his home.

Part art history, part travelogue, through in this case, Spain, to visit a country through the eyes of an artist and his works, is a unique experience. The fortunate thing right now is that if the trip to Spain is a bit too ambitious a project, then the retrospective exhibition also commemorating his centenary coming to The Philadelphia Museum of Art February 2005 will make an appropriate substitute. The exhibit will have 210 of Salvador Dalí’s works, 150 of which are paintings. The museum is the second of two locations featuring the centenary exhibit, the first location having been Venice.

Although a cursory view of Dalí’s work puts him in the surrealist camp, Michael Taylor, Muriel and Philip Berman Curator of Modern Art at The Philadelphia Museum of Art, and curator of the Dalí exhibit in Philly, explains that Dalí doesn’t quite fit in with the surrealists, and that although they appreciated him his apolitical stance lead to his estrangement. “The rest of the surrealists could not understand Marcel Duchamp’s continued support of him and his work,” explains Taylor. In Taylor’s view, “Duchamp felt that a lot of art stopped at the retina and didn’t extend to the mind and he felt Dalí’s work always went to the mind.” The opportunity to travel to Dalí’s home, to see Dalí’s Spain, confirms that to categorize him solely as a surrealist would be inaccurate, and as the other surrealists seemed to attest, incorrect given what appeared to be his political ambivalence.

It is a unique approach to travel, and by extension a unique approach to understanding an artist, to visit his home and the locales that in large degree constituted his inspiration. In this instance to see the breadth of Dalí’s work, from his pieces at Fundació Gala-Dalí in Figueres to those at Centro de Arte Reina Sofia in Madrid, confirms his technical brilliance and his acumen for “pastiching” different styles. He had an ability to whisk through styles from impressionism to cubism to surrealism and mediums from paint to photography to sculpture that is at least in part what gives him artistic stature.

One small example is at the Fundació, where they house his fine jewellery collection. In it the viewer finds a ruby encrusted beating heart brooch, part catholic iconography, part gore, part fashion. To experience the scale of Dalí’s work and influence is to see a precursor to post-modern pluralism.

Venture over to his home in Portilligat, just opened to the public in 1997, and his rare appreciation for the full spectrum of low, middle and high culture becomes evident. The swans as depicted in Swans Reflecting Elephants, perhaps pets once, are now taxidermied and on display in his former library. Much of what might be expected in terms of Dalinian eccentricities are in his home: a perfectly acoustic dome for after dinner cocktails, kitsch-y patio furniture to rival any white trash deck, and an enormous (for a cricket) cricket cage in his bedroom so that he could listen to the cicada’s song before sleep each night.

Basket of Bread, 1926, St Petersburg (FL), the Salvador Dali Museum.

In keeping with his penchant for extremes, Dalí was expelled from art school, twice. At the Real Academia de Bellas Artes in Madrid the director explains how Dalí was finally and firmly expelled for stating that he knew more about art history than his examining professors and therefore should not have to be subjected to their tests.

And there is the rub. For all the modernity and avant-gardism attributed to Dalí, Dawn Ades, Professor of Art History at the University of Essex and Director of the Research Centre for Studies of Surrealism and its Legacies in England, foremost Dalinian and curator of the Venice retrospective, underlines that Dalí (and Picasso) took the lead in removing the veto imposed by other artists, especially around the 1920s, on looking at past masters.

Dalí was especially interested in showing the formal antecedents to the surrealists. During his “schooling” he spent much time at the Prado, studying the masters. Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights at the Prado is rife with the kind of double imagery that Dalí is known for in the mainstream. Ades points out the links between Dalí and the masters who influenced him.

The Prado also holds the most exquisite collection of Goya paintings. One to seek out is Saturno. As Ades explains, “Dalí’s father is a ferocious figure, always a lion in Dalí’s paintings. Saturn was one of the terrifying paternal images.” In Goya’s Saturno you may note “the soft construction … the body is dull and not like flesh but like bone or wood, the legs and arms. Remember how Dalí plays on the disquieting relation between bone and flesh, disintegration. There is a double image in the Goya—the bottom right—it could be a knee or another son bending down in fear. The same use of scale is in Dalí’s work … and that should never be confused with size.”

Dalí’s works are alive with these double images. He felt that the more paranoid you were, the more you saw. Dalí’s double images are like apparitions disappearing into the image. The Endless Enigma at the Reina Sofia is the high point of this technique. He infused several images into this work. Go there and find: a boat, a greyhound, still life with pears, the face of Lorca, the back of a woman, the philosopher reclining, a horse, and a mandolin.

A Dalí pilgrimage requires a trek to Fundació Gala-Dalí at Figueres, which is part of the Dalinian Triangle located in the Amperdam region: Figueres, Portilligat and Pubol. Dalí bought the foundation in the late 60s as a local museum to show his work. He opened it in the early 70s after spending some time on the design. It is now also his tomb site. But in Dalí’s mind it was not to be a cemetery for works of art. The museum itself was to be seen as a surrealist object, and so he spent 13 years creating the centre. He worked to bring works of art from abroad to the museum and also put together his collection of art for display. And so in the museum, along with an extraordinary array of Dalí’s work, almost depicting every genre he experimented in, is an entire floor dedicated to the great masters.

Apparition of a Face and Fruit Dish on a Beach, 1938, Hartford (CT), the Wadsworth Atheneum.

How the museum also became his tomb site is somewhat controversial. Pubol, a second point on the Dalinian Triangle, is where Gala’s (his wife’s) castle is located. This is where Gala spent most of her time near the end of her life. Dalí had actually designed two tombs, which can be found at Pubol castle, and which have a tunnel between them so that Gala and Dalí could join hands in their death. Visit the museum and if you are fortunate, one of the guides may divulge the machinations behind how Dalí actually ended up at the museum rather than at the castle with Gala.

A visit to the castle is important because it allows a more personal and incisive view into Gala that is often overshadowed by the many dalliances. The pervasiveness of her presence in Dalí ’s art and the consistency of her presence in his life at least hints at the possibility that she was more than merely a model for his paintings. And so it becomes a part of the process of the revision of history or maybe the greater understanding of a specific example that can at some point transcend to a universal application.

Surrealism may seem obscurantist to some but Dalí is well worth the investigation. His impact extends deeply into mass culture and his foray into other genres such as fashion, jewellery, photography, film, even commercials, are emblematic of his understanding of a certain commercial reality. It could just be however, that at a certain point the understanding of this commercial reality leads to a condonement of it, which in today’s climate seems ineluctably headed towards greater compromise. Fighting words for another article perhaps.

But fundamentally a joy to be derived from such a journey, vacation, intellectual exercise, is the experience of the intratextuality between Dalí ’s own works and the intertextuality between his works and that of his peers, and finally of the masters he admired.

Visit the exhibition in Philadelphia or the Dalinian Triangle in Spain to get a glimpse of this extraordinary 20th century figure. The payoff will be enormous.

Just a taste may touch your palette when you look away from inspecting Goya’s Saturno; just over your shoulder to the left is Duelo a Garrotazos which gives an interesting perspective on Dalí ’s ostensible political ambivalence towards the Spanish Civil War. Ades elaborates, “The way Dalí viewed civil war was an emergence of irrational hate and violence.” In this painting there are two figures mindlessly bashing each other into the ground. Ades contends that Dalí shared with Goya this unflinching view of violence. This image is not so far from Beckett’s theatre of the absurd, two men sinking into the ground (think Happy Days) who could easily save themselves and each other (Waiting for Godot), if only they would put down their sticks.

To see your world through an artist’s eyes, to participate in the act of creation, or in Barthesian terms, to create a writerly work of art, rather than to simply and passively see the artist’s world through your eyes; that is the ultimate goal of retracing the artist’s steps. It is not to recapture their past but to engage, to spark something newly created, even if it appears to be as straightforward as connecting the dots.

The Salvador Dalí retrospective exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (February 16-May 15, 2005) was made possible by Advanta.

Artwork usage courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art.