Fashioning Canada Since 1867

Sesquicentennial style at Ontario's Fashion History Museum.

The fuchsia and orange gown by Toronto designer Lucian Matis that Sophie Grégoire Trudeau wore to the state dinner in Washington with U.S. President Barack Obama last year highlights a new exhibition opening this week at the Fashion History Museum in Cambridge, Ontario.

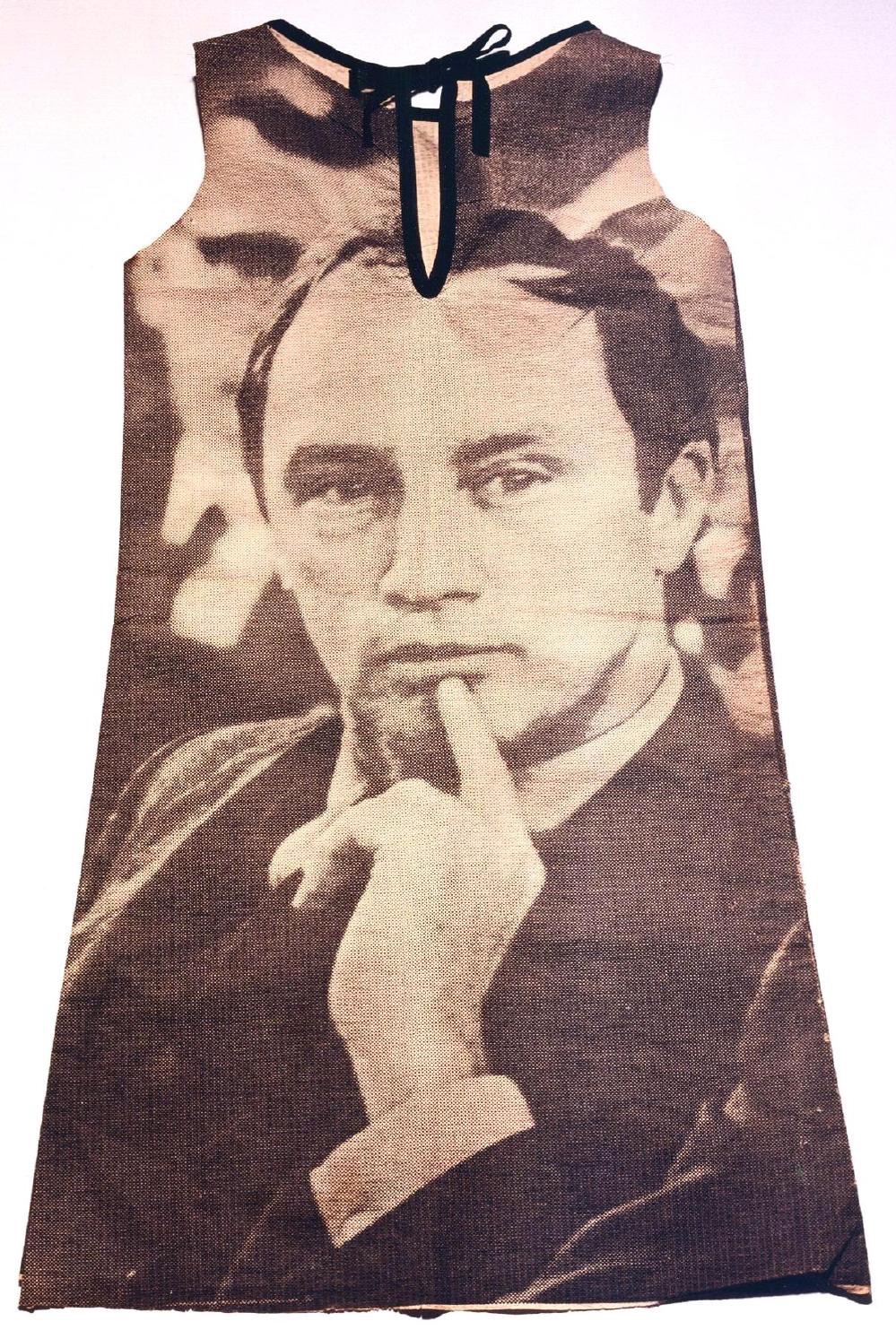

Fashioning Canada Since 1867, running from March 15 to December 17, 2017, coincides with the 150th anniversary of Confederation and shows how Canadian style has evolved along with the country. There are over 64 items on display in the museum (itself housed in a former 1928 post office) ranging from the practical, bulky knit sweaters to hand-beaded dresses worn in the presence of world leaders.

The fashion reflects the nation, tracing its evolution from dull colonial outpost to vibrant international player, observes FHM co-founder Jonathan Walford, a founding curator of Toronto’s Bata Shoe Museum who opened the FHM with fellow co-founder Kenn Norman in 2015.

“Fashion encompasses everything,” Walford elaborates. “You can read in it all the outlining influences, the social, the cultural, the political, and the economic. It’s never just about clothes.” The four central displays describe distinct stages in the development of Canadian fashion over the last century and a half. Posing the question, “What is Canadian Fashion?” the first examines how geography, in particular Canada’s harsh climate, along with the fur trade, helped shape a national identity through clothing custom-made for life outdoors.

The fashion reflects the nation, tracing its evolution from dull colonial outpost to vibrant international player.

Items include a head-to-toe woollen outfit created for a member of Ottawa’s Snowshoe Club in 1890, several variations on a theme of a Hudson’s Bay striped blanket coat, Inuit knits, First Nations-inspired parkas and mukluks. Mixed in with the historical are pieces by contemporary Canadian fashion brands like Canada Goose, Linda Lundström and DSquared2, linking fashion today to what came before.

Next, Clothing the Nation takes a more indoor view of the country’s sartorial leanings. Presented here are bustles and taffeta, sleek Edwardian silhouettes and large plumed hats, gold silk day dresses, and matching gloves. Some of the clothing came from abroad, accumulated by Canadian high society women in London for parties back home. As the following section, Made in Canada shows, other items were purchased locally at Eaton’s, Creeds, and Dalliards, an early Canadian department store chain, or else were made by professional dressmakers and tailors plying their trade in communities across Canada.

By the 1960s, Canadian fashion was starting to become internationally known, spearheaded by homegrown designers like Claire Haddad, the first Canadian honoured with a prestigious Coty American Fashion Critics’ Award, and Arnold Scaasi, the Montrealer born Arnold Isaacs who created gowns for first ladies in the U.S., including Mamie Eisenhower, Barbara Bush, Hillary Clinton, and Laura Bush, as well as A-list celebrities, among them Elizabeth Taylor and Lauren Bacall.

These Canadian fashion innovators broke ground for the designers who follow after in the 1970s, the focus of the final display, The Canadian Brand, which is where in the Lucian Matis dress is, among other pieces. The colours and shapes are as plentiful here as the names assembled, Wayne Clark, Simon Chang, Lida Baday, Jean-Claude Poitras, and Bernard McGee and Shelley Wickabrod for Clothesline to name a few.

Walford says this eclecticism mirrors Canada as a whole, a country not cut from a single cloth but representing many threads from around the world to form an attractive cosmopolitan fabric. “The fashion tells its own story,” he says.

Photos courtesy of the Fashion History Museum.

_________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter.