Omega at the Olympics

Keeping time.

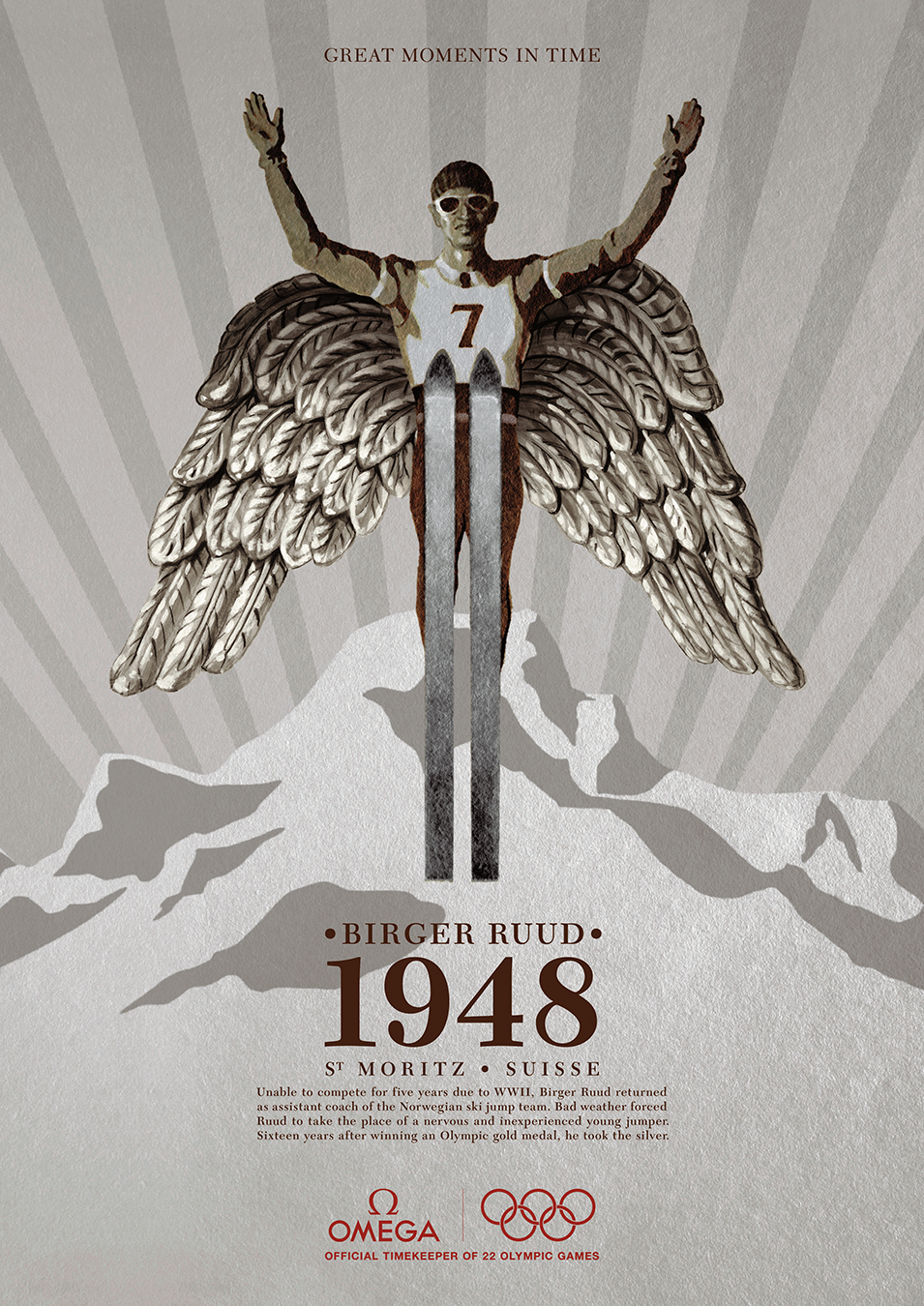

1948 Omega Olympic poster.

It is possibly the one commodity that we most take for granted.

The tracking of time began as early as 4000 BC with the sundial. The Egyptians measured time by the direction of the shadows cast by the sun, dividing the day into 12 equal parts, giving us the familiar 24-hour day. Astronomers around 200 BC invented sophisticated astrolabes that plotted the movement of the planets and the moon relative to the stars. Other advancements in marking time included the obelisk, the hourglass, the water clock, and the candle clock. The 13th century saw the invention of the mechanical clock. And although there are a few watchmakers who claim to have invented the first wristwatch, Louis Cartier is responsible for popularizing it over the traditional pocket watch in the early 20th century. (In 1904, Alberto Santos-Dumont, an early pioneer of aviation, asked his friend Cartier to create a watch that he could wear on his wrist during flight.)

Timekeeping devices have similarly evolved over the centuries and now incorporate astonishing precision and reliability. Horologists work in the scope of millimetres to ensure a watch’s performance is nothing short of perfection.

Such accuracy is never more crucial than at the Olympic Games. Swiss watchmaker Omega holds the coveted role of official timekeeper for the 2010 Olympic Games in Vancouver. This is the 24th time that Omega, part of the Swatch Group, the world’s largest watchmaker, will take on the role of official timekeeper, and it has an array of high-tech innovations, including state-of-the-art timekeeping and data-handling equipment, to make sure its results are absolutely and unquestionably accurate. “Athletes train for five, 10, 15 years, and they have 50 seconds to become champion,” says Christophe Berthaud, general manager for Swiss Timing, which is also part of the Swatch Group. “We have to be accurate. We cannot make mistakes.”

Vancouver 2010 Limited Edition Seamaster Diver watch.

Omega’s tradition of sports timekeeping goes back to 1898, when it crafted the first chronograph—a 43-millimetre CHRO calibre movement in Lépine and hunter styles. A button integrated into the crown stopped the time, and a sweep hand measured to one-fifth of a second. Adhering to a frequency of 18,000 beats an hour, it included a 30-minute elapsed time subdial at 12 o’clock and a continuously running subsidiary seconds dial at 6 o’clock.

Omega first kept time at the 1932 Olympic Games in Los Angeles; it had one technician with 30 high-precision chronographs. For the 1936 Olympic Games, watchmaker Paul-Louis Guignard took a suitcase with 185 chronographs from Omega headquarters in Biel-Bienne to Berlin. Omega has introduced several innovations over the subsequent decades that are now synonymous with sports timing.

“People take this for granted,” says Stephen Urquhart, president of Omega, pointing to his watch. (In true aficionado style, Urquhart wears watches on both wrists.) “You look at a sporting event and see a little time down there [on the TV screen]. They have no idea what’s behind that. What’s behind the timekeeping at the Olympic Games … it’s a big, big investment—and I don’t just mean money but in people, in technology.”

When Omega is on the job again in Vancouver, it will be using 100 kilometres of cables and optical fibre and 200 tons of timing and scoring equipment. There will be 218 technicians and engineers to ensure that the clocks are ticking, and ticking on time.

At the 1932 Games, the official results were given at fifths and tenths of a second. Results were first recorded to the nearest hundredth of a second in 1952; the era of quartz and electronics had arrived and with the Omega Time Recorder, which was mobile and independent of the electrical network, the results were printed out on a roll of paper. And the 1968 Games in Mexico City/Grenobal, France, saw the debut of in-pool touchpads, which recorded the time precisely when swimmers touched them. This innovation put an end to a number of heated debates concerning the swimming competitions.

The Olympic Games continued to inspire innovations in sports timekeeping, and computers entered the arena in 1980 during the Olympic Games in Moscow/Lake Placid. In the 1988 Games in Calgary, all of the measured times were saved, distributed, and printed by computer. At the Beijing Olympics in 2008, Omega premiered the latest generation of digital cameras, which snapped an incredible 2,000 photos every second, to determine precisely when an athlete crossed the finish line.

1976 Omega Olympic poster.

Sports showcases rely on the integrity of their measuring and timing systems as much as they rely on their ability to broadcast ever more sophisticated programming. Today’s systems are light years away from the early days when synchronized chronographs recorded the time the skier started and finished their run, and the results were pinned to a notice board several hours later.

The Whistler Sliding Centre is the venue of the bobsleigh, luge, and skeleton competitions for the Vancouver Games. The track may look benign on television, but the athletes are barely visible as they whistle past at top speeds of just over 140 kilometres an hour. There are 42 pairs of infrared emitters and receivers along the 1.45-kilometre track that send a time-tagged message to a central computer in the on-site control/timing tower whenever the light beam is broken. There are two systems working in parallel: a master and a backup. Able to withstand extreme conditions, they are also equipped with their own heating system.

“The heart of the operation is the timing room,” says Berthaud. “There is backup upon backup upon backup, and we can switch from one to the other easily. The system does not fail.” After all, the difference of a hundredth of a second could mean the difference between gold- and silver-medal honours, or even elevate an athlete from being a winner to a record holder.

The Games offer Omega one of the most effective international marketing platforms in the world, reaching billions of people. It comes at a cost, but as Urquhart says, “It’s a cost mainly in-kind in technology. We are not giving the IOC [International Olympic Committee] millions of dollars to just put our name out there. We have the infrastructure in the group with Swiss Timing. We have all the equipment within the group, we have the timekeeping, we have the technology. And so the question is, how can we use it in the best way?”

On February 12, 2010, when the Games of the 2010 Olympiad begin in Vancouver, the world will be watching. And Omega’s timekeeping professionals will be poised and ready, recording, yet again, historic Olympic moments.

Photos ©Omega.

See more Omega Olympic moments.