-

“Clay, clay for the hands to play the mind serious.” —Sorel Etrog.

-

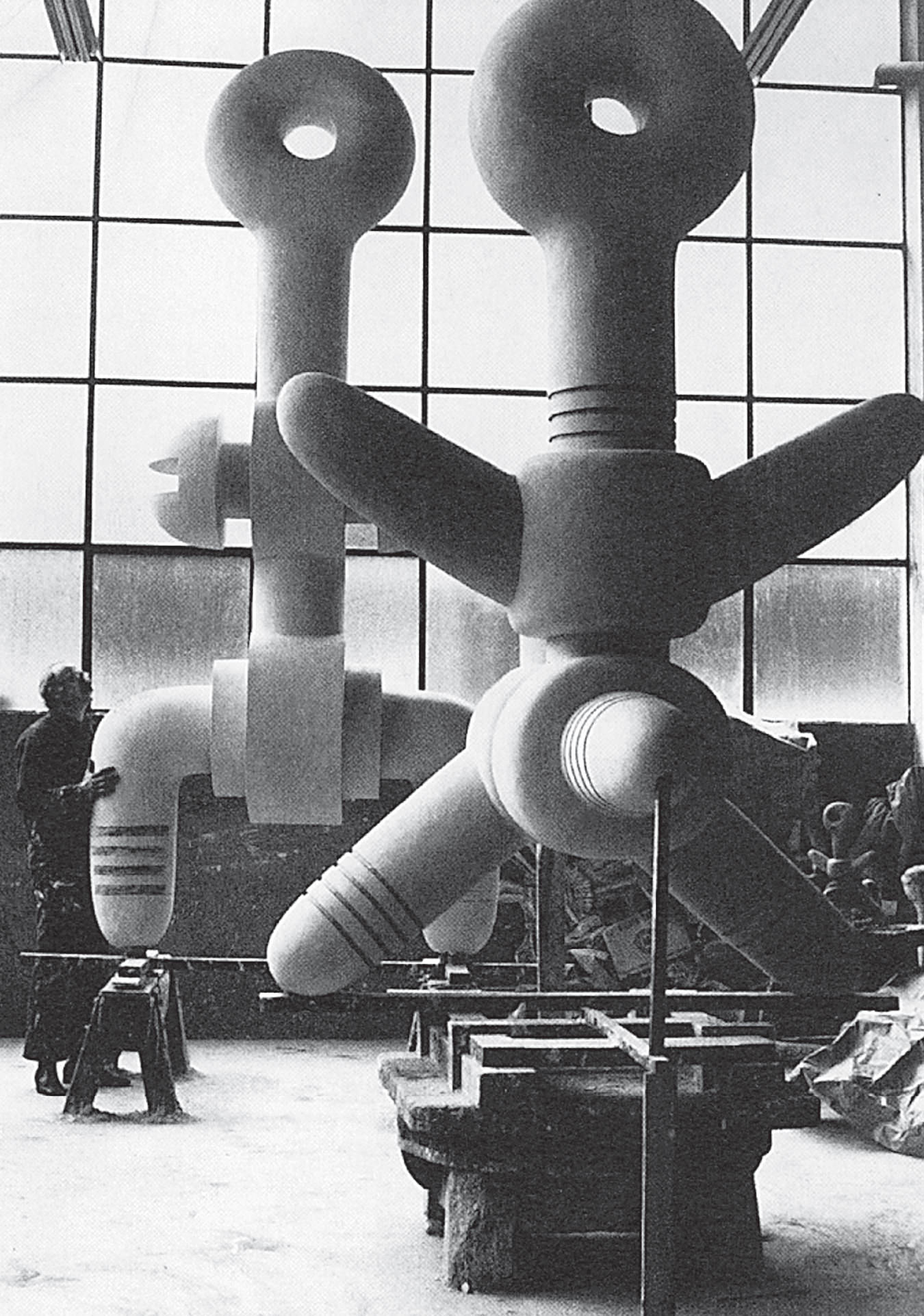

Dream Chamber by Sorel Etrog, now in the Prime Minister’s residence at 24 Sussex Drive.

-

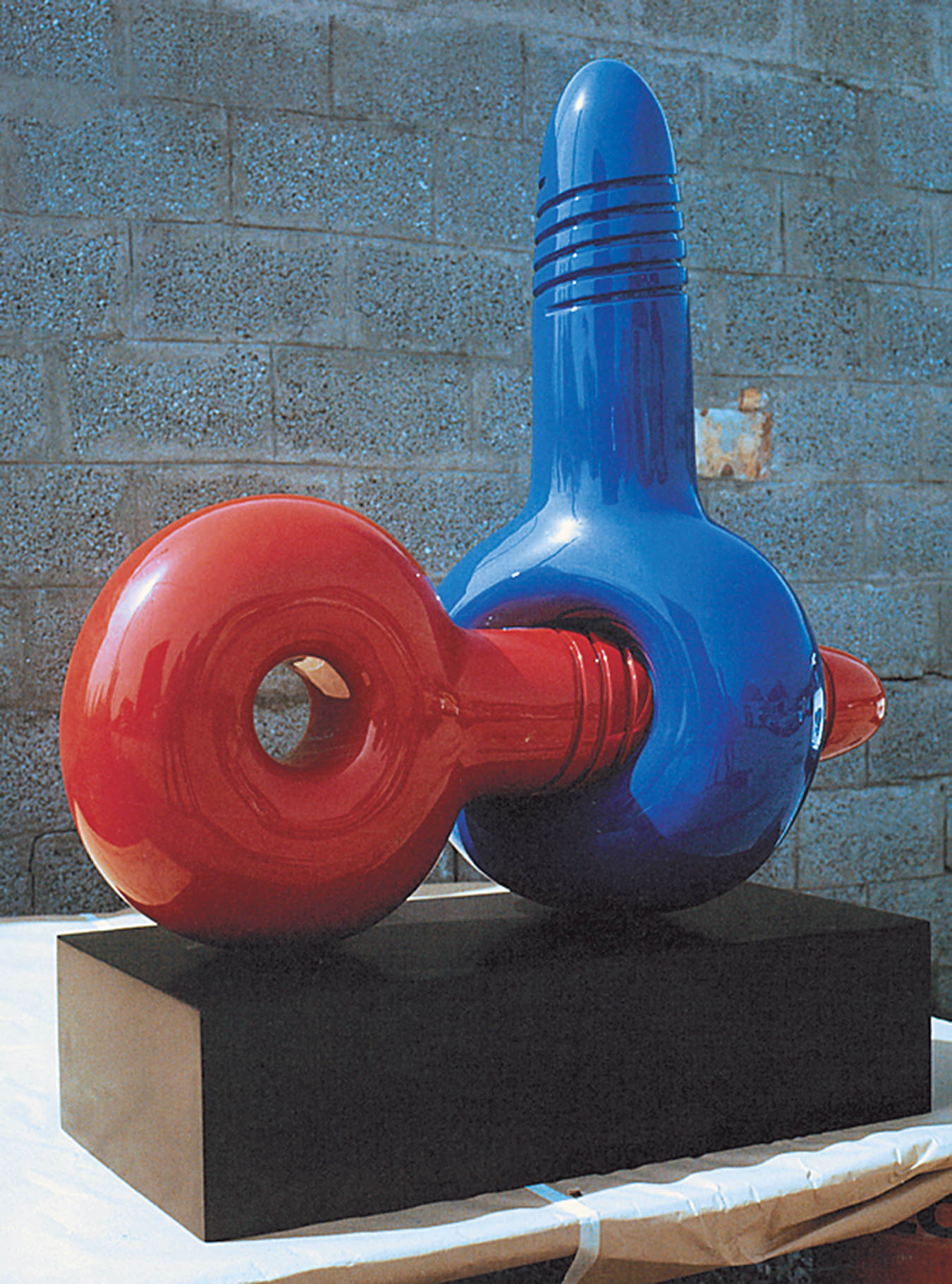

Castor and Pollux by Sorel Etrog.

-

Sadko and Kabuki by Sorel Etrog.

-

Northeast by Sorel Etrog.

-

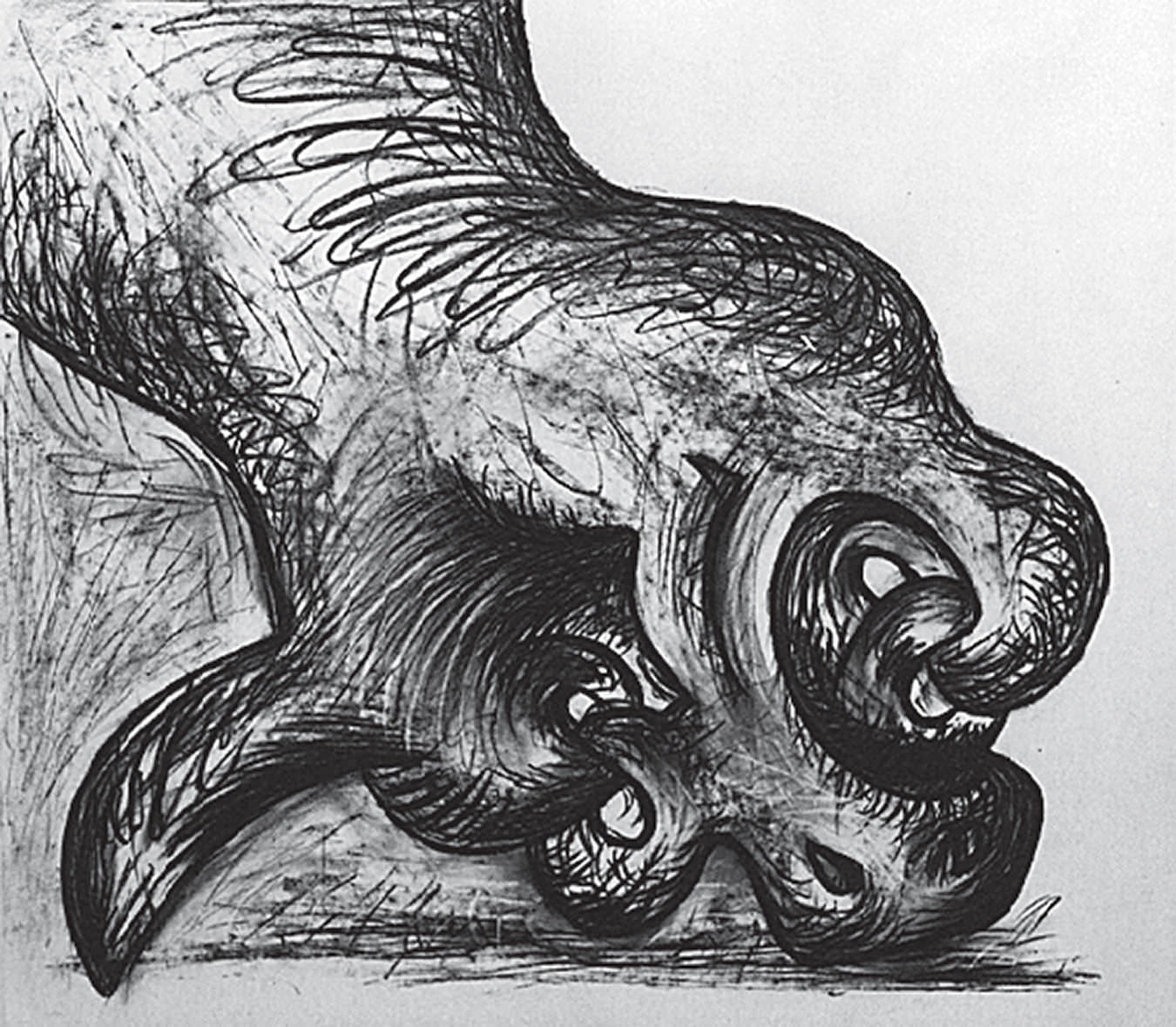

An homage to Picasso by Sorel Etrog: a detail from Targets.

-

A metal bull’s head, another homage to Picasso by Sorel Etrog.

-

Sorel Etrog’s sketch of Samuel Beckett.

-

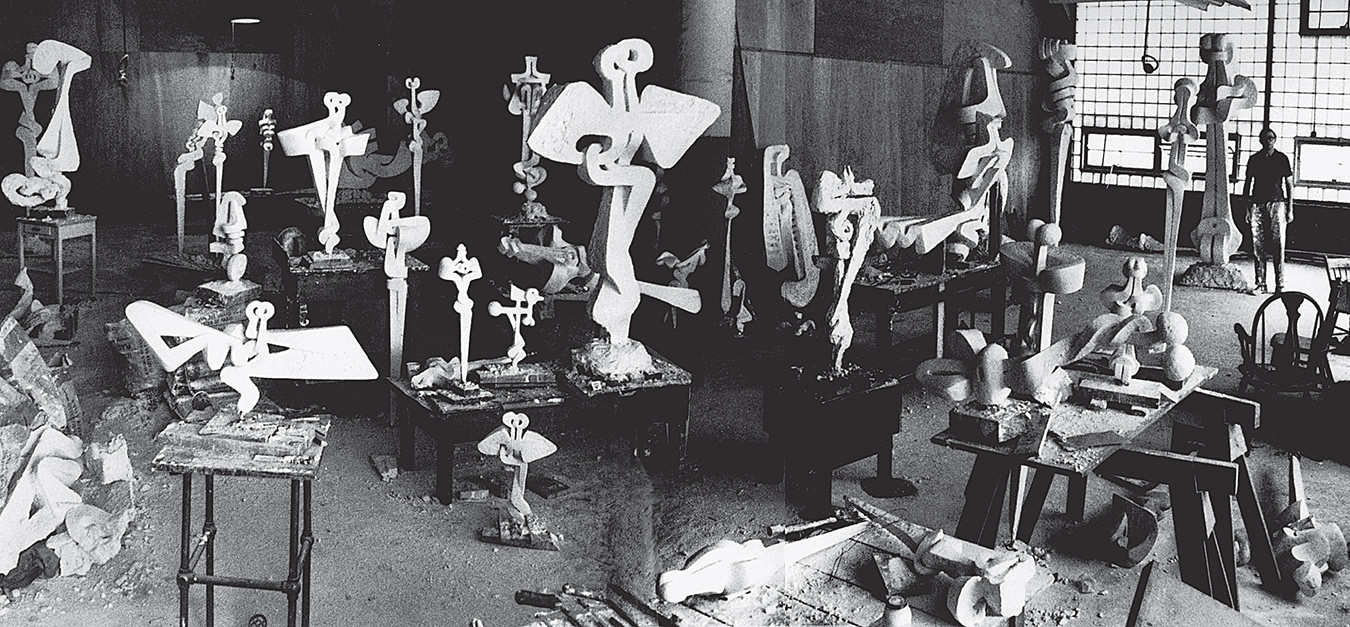

Sorel Etrog’s studio.

-

Sorel Etrog with Eugene Ionesco.

-

Picton, from Sorel Etrog’s Hinge period.

-

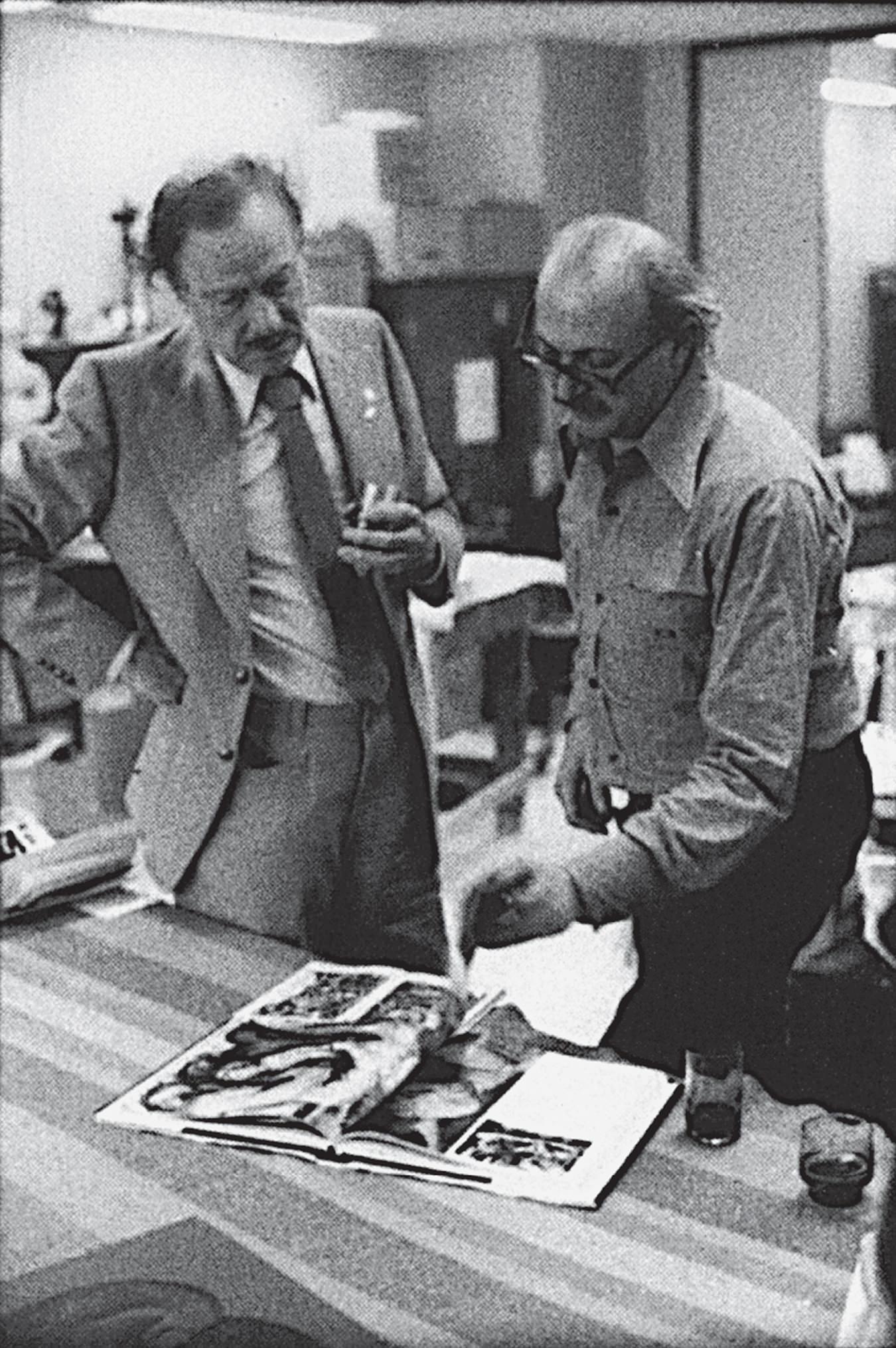

Marshall McLuhan with Sorel Etrog.

Sorel Etrog

Recollecting things to come.

Standing in Sorel Etrog’s labyrinthine studio in downtown Toronto, I am overwhelmed by the extraordinary archive before me. I have come to assist Etrog in the final image selection for his long awaited monograph. The book, Sorel Etrog, published by Prestel of Germany, was due for release in autumn 2001. Before we begin, Etrog takes me on a tour, his habitual cigarette, with an implausibly long and tenacious ash, hanging crookedly from his lips.

Etrog’s studio occupies almost an entire floor of a residential apartment building near Yonge and Eglington, but the atelier remains quite removed from the neon clatter below. A hallway with elevators divides the studio into two sections, half functioning as the artist’s work space, library, and second home, the rest as office and warehouse (one of a half-dozen throughout the world).

A locked door reveals chamber after chamber of ghostly figures; sculptures with names like Ritual Head, Dream Chamber, Introvert, Pistoya (Mother and Child) and Castor and Pollux stand at attention as if in the quiet of a museum. Here is a collection worthy of the Tate Museum, the Guggenheim, the Hirshhorn or any of the hundreds of institutions that collect Etrog’s work. On the walls hang photographs of such friends and collaborators as Marshall McLuhan, Samuel Beckett and Eugene Ionesco.

The impressive clutter of life-size bronze sculptures and work tables holding hundreds of wax maquettes suggests feverish creativity. But despite these, and stacks of paintings, drawings and etchings, and books overflowing their shelves into great piles on the floor, Etrog has laid out a meticulously ordered plan. Step by step, every reproduction will be assessed. This is the final phase of a three-year project which had to be completed before the artist would release the book to the publisher and a very personal history to posterity.

On the floor lie perhaps two dozen images representing more than 90 works from Etrog’s Painted Construction period of the 1950s. In these, we see the groundwork for a unique visual vocabulary described by critic Pierre Restany as Etrog’s “thesaurus of theme and form.” The labour-intensive, emotionally difficult process begins, reducing a life’s work to a few images that will accurately reflect Etrog’s sense of artistic evolution; although for Etrog, favouring certain works over others means eliminating essential pieces of an elaborate puzzle which form a career spanning five decades.

Found objects, Etrog says, “provoke thoughts. I see in them potential transformation…not what they are, but what they can become.”

Keys to this multifarious output lie in Etrog’s childhood. Born into a Jewish family in Jassy, Romania in 1933, Sorel was seven years old when Nazi Germany began its occupation. By the time he was nine, Sorel says, “nothing could shock me ever again.” His father was one of only a few to survive a massacre of 10,000 men herded into a courtyard and gunned down. While Etrog’s father lived, it took him two years to walk again. Sorel would also witness a playmate shot in the street by soldiers. Such were the formative years for an artist whose work speaks always to the human condition. Although his art rarely refers overtly to the Holocaust he witnessed and survived, Etrog’s struggle to reconcile the story of human affliction is omnipresent.

Etrog credits his burgeoning interest in art to an early exposure to carpentry in his grandfather’s workshop. His precocious love of the tools he yearned to use was translated into a respect for materials, attention to detail, and a level of craftsmanship which, combined, form Etrog’s signature.

Etrog’s studio is a living archive of the artist’s evolution. Each of his seven periods is represented, all revealing something essential about their creator. And here also are seemingly insignificant artifacts, strangely shaped pieces of styrofoam, plastic milk crates, sardine can lids, each an example of something that caught the artist’s eye and intrigued him enough to collect for further consideration.

This childlike fascination with found objects has led Etrog to many of his signature motifs. Found objects, Etrog explains, “provoke thoughts. I see in them potential transformation…not what they are, but what they can become.” An eyescrew picked up on a road inspired the Screws and Bolts sculptures of the early 1970s, Etrog’s most overtly erotic works. These are at once the most mechanical and sensual sculptures of his career, while the bold and good-humoured use of strikingly rich automotive paint reflects not only Etrog’s wit, but also his need to explore the spectrum of colour. When a viewer comments on the direct sexuality of Northeast or Sadko (Bow Valley Square, Calgary) , he replies with a mischievous smile and paraphrases Freud: “A pencil is sometimes just a pencil.”

The image that dominates the studio is the 1969 charcoal drawing Targets, Etrog’s homage to Picasso’s Guernica. The frieze-like drawing (365.76 x 152.4 cm) articulates pain and suffering with extraordinary candour. Etrog has replaced Picasso’s human figures with linked bulls. Locked together in a torturous chain, the bulls represent the defenceless innocence of victims and the universality of suffering. Just as animals led to the slaughter are vulnerable and powerless, so are the victims of war. With over 100 studies on the same subject, Etrog captures the turmoil and absurdity of war, while simultaneously investing his empathy with the innocent and his conviction in the possibility of hope. Etrog exhibits his tremendous ability as a draughtsman as he balances human frailty against the strength of his faith in humanity. The haunting, large-scale work resonates with visceral force and ineffable tension.

Locked together in a torturous chain, the bulls represent the defenceless innocence of victims and the universality of suffering.

Discussing the recurrent motif of the bull throughout his oeuvre, Etrog credits the influence of Picasso, but explains that as a child in Israel, where he settled in 1950, his sole exposure to visual arts was through the iconography of Catholic churches and Jewish synagogues. As Jewish law forbade figurative images, animals, invested with human dignity, served as the subjects of frescoes decorating hallowed walls. Etrog’s bulls allow him to convey many layers of meaning, illustrating dialectics between brutality and humanity, responsibility and innocence, evil and good.

Fluent in five languages, Etrog is familiar with the 20th century sense of dislocation and cognizant of its importance to his art. Speaking to the notion of exile, whether forced, as in his flight from Romania to Israel, or chosen, as in his decision to relocate first to New York, then to Toronto and to Italy in between, Etrog explains that exiles are forced to “compensate for being an outsider. Without the comfort of one’s customs, one must have the strength to adapt to the environment and develop a new relationship not just with others, but also with oneself.”

This constant re-examination of place and self has shaped his work profoundly. He credits his initial exposure to classical music in Tel Aviv with expanding his artistic consciousness. Not only do many of his works allude to musical influences, and the actual shapes suggest instruments, but he describes his work in musical terms. The dots, “chords” and arrows of his painted constructions, for example, are “soloists that jump from the piece, connect multiple planes and give the eye direction.” Etrog says that individual instruments in an orchestra are sometimes given supreme importance, and his assemblages feature elements that do the same. “Creation is part of your inner rhythm, that you carry wherever you go,” he says. “The mysterious playbacks that then recur act like a familiar and identifying gesture.”

The story contained in Etrog’s art is dialogue between different, often contending forces. The techniques and devices employed have evolved, but they always maintain this dialectical tension, whether articulated through the dots of the painted constructions, the links bonding the bulls of Targets, or the rivets adhering to the limbs of the formidable King and Queen. Describing the importance of tension and release, Etrog touches on a subject that differentiates him from such 20th century sculptors as Henry Moore, whose preoccupation with weight and mass “root them to the ground.” Etrog’s totemic sculptures appear to “grow as if from nothing.” He explains that his Standing Figures grow from the ground, are interrupted at the hips, where “something inexplicable happens” for a brief moment before the rhythm continues until the explosion of the shoulders or the head. “It is about timing; if the tension of the piece were cluttered, you wouldn’t have such release. It is the silence before the crescendo.”

His Standing Figures, growing from the ground, are interrupted at the hips, where “something inexplicable happens” before continuing to the head.

For Etrog, the human head is a landscape in which to explore and articulate the tension between the interior life of humans and the exterior reality they face. His study of the subject culminates with the masterpiece Dream Chamber (1976, bronze, 157.5 cm, now at the Prime Minister’s residence, 24 Sussex Drive, Ottawa). In his 1982 collage/book Dream Chamber: Joyce and the Dada Circus, Etrog hints at the obsessive power of the mind and his fascination with access to what is usually locked away and inscrutable:

Doors that open from the inside only;

Outsiders use other doors.

Dream Chamber exemplifies Etrog’s Hinge period and, more specifically, his suggestive series of Introverts. Integral as a device for what Etrog terms “contact and articulation,” the image of the hinge preoccupied the artist through much of the 1970s, and allowed him to imply the possibility of movement or change in what seem the most immutable of materials. While the massive taut sphere suggests an impenetrable vault of memories, ideas, emotions and subconsciousness—mysteries locked within the mind—the hinges that cut into the surface tease with the potential of opening and revealing. At any moment, the mystery could unravel. Tension and release play formal and psychological roles in both his sculpture and two-dimensional work. At once elements pull together and apart, are stuck and freed. Shapes are united and simultaneously rendered independent. Works such as Castor and Pollux, where independent forms are linked and bound in order to provide a freedom of intimacy, demonstrate Etrog’s mastery in harmonizing elements that are normally discordant.

Despite multinational exhibitions, despite sculptures that reside in an astounding number of public places in Canada and other countries, and despite a list of public collections that reads like a litany of the finest institutions in the world, Canadians are relatively unfamiliar with a creator in their midst regarded as one of the great artists of the twentieth century. As early as 1967, Sir Philip Henry, then Director of the National Gallery in London, England, recognized Etrog as “one of the superb technicians of metal and bronze” of his time and declared it “high time there was a monograph on his work.”

Some 58 publications later, the release of the Prestel book and a concurrent exhibition at Vancouver’s Buschlen Mowatt Gallery afforded a unique opportunity to place Etrog in the proper context. At the October 2001 retrospective, the full range of all seven periods, including Etrog’s latest wall-mounted composites, was exhibited for the first time in Canada. The book’s release and the installation of over a hundred drawings, paintings, composites, maquettes, and sculptures life-size and monumental drew Sorel Etrog out from the shadows to assert a commanding presence on the Canadian and international stage.

To a great extent, the artist’s relative anonymity represented a conscious choice. In the last twenty years or so, Etrog has retreated from the spotlight, preferring the solitude of his studios (at various times in New York, Toronto, Israel, France and Italy), collaboration with confrères (Etrog illustrated books by Ionesco, Beckett and others), and the audience for his work. His retreat in 1963 from New York to Toronto after a masterful debut solo exhibition at New York’s Rose Fried Gallery, heralded by The New York Times as a “monumental arrival,” indicated Etrog’s preference for quiet rather than applause. “Solitude,” he says “is a great luxury. Very few people can afford it.” He admits that living like that is not easy, that solitude “has its price,” even with its artistic rewards. While a performer is nourished by the immediate response of viewers or listeners, Etrog works always with an invisible audience.

While his commitment to his work has led Etrog along a solitary path, he is no recluse. His anecdotes are full of mirth, whether he is recalling a road trip with Isamu Noguchi through Tuscany or relating how he and Restany would spend hours engaged in a random dialogue of “free-writing,” reminiscent of the automatic writing of the Surrealists, in which one would write a word on a piece of paper and pass it along for another to respond with another word and return it; back and forth it would go. But Etrog’s interests go beyond intellectual games. He is always eager for a tennis match and he is a devoted Toronto Maple Leafs fan.

At 68, Etrog is remarkably agile, but conscious of the fact that time is fleeting. The sense that he might not accomplish everything his mind imagines haunts him. As a result, the prolific artist alternates furiously between writing, modelling his wax maquettes, painting, doodling, and experimenting, always at a feverish pitch. He searches to capture the seconds of unfettered imagination, the moments of creation before the “tyranny” of judgement steps in to interfere.

He exudes passion for the continued exploration of themes he initiated as early as 1952. Guiding a visitor through his modest art collection, mainly primitive African and Oceanic sculpture, he revels in their sophisticated simplicity; his admiration evident for anonymous, inventive artists who had such an impact on much of the art of the twentieth century, including his own.

Like solitude, time is a luxury for Sorel Etrog. He confronts his half-century as a working artist, evidence of which surrounds him everywhere, and anxiously anticipates what to do next. “You see the things I’ve done,” he says. “I see the things to accomplish.”