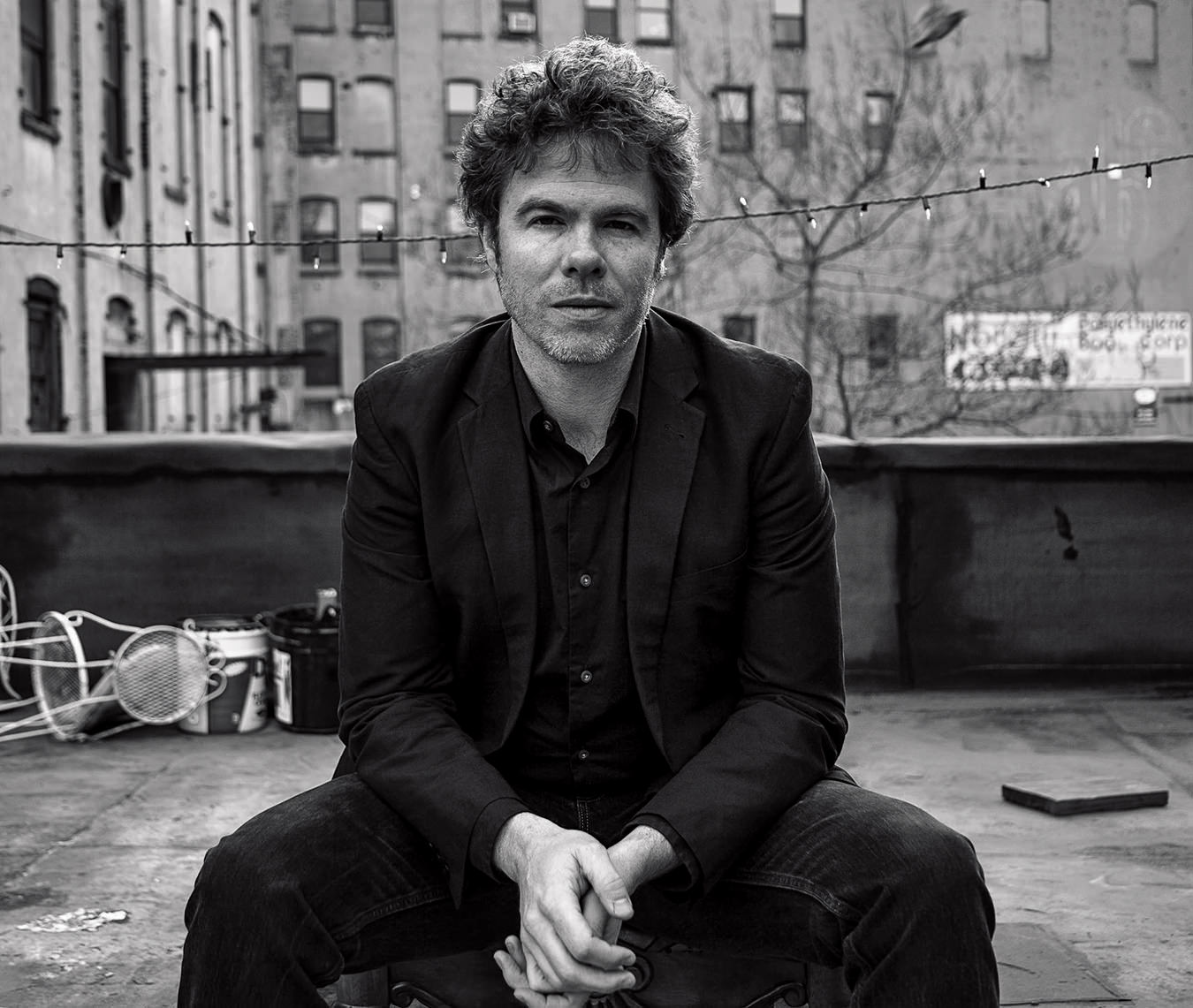

Making Memories With Casey MQ

The singer-songwriter on turning from COVID-era dance party phenom to cerebral crooner.

Casey MQ, A.K.A. Casey Manierka-Quaile, is comfortable talking over Zoom. Calling from his new home in Los Angeles, the boyishly handsome Southern Ontario native flits across my screen with ease, displaying the adeptness with digital communication that he developed as the organizer, host, and frequent headliner of the COVID-era queer dance party, Club Quarantine. Founded along with fellow Toronto-area creatives Ceréna, Brad Allen, and Mingus New mere days after the first lockdown was announced in March 2020, Club Quarantine experienced a meteoric rise in the weeks following its spontaneous debut, featuring pop stars such as Charli XCX and Lady Gaga, and collaborating with brands such as Absolut Vodka.

Before brushing virtual elbows with A-list celebrities over Zoom, Casey MQ had a typically Canadian childhood followed by a typically trying start to his musical career. Born in Hamilton, he grew up in what he describes as a not particularly musical household, and he found his way to the piano like many do, because he was told to. “All the kids in my family, we all had to learn piano. My mom wanted us all to learn it. I think I was, from her words, the only one who really liked it.” Balancing his passion for the piano with equally strong ones for theatre and dance, his childhood centred around the arts. But when it came time to pick one to pursue following high school graduation, music, piano in particular, won out. Similarly to when he first adopted the instrument, his decision was hardly a conscious one. “It was just natural to keep working on it,” he says.

After moving to Toronto in 2014, he began taking odd musical jobs to pay his bills while working toward his creative goals. Alongside stints playing the piano at bars, funeral homes, and retirement communities, he worked as a musical performer at local dance competitions. “I would perform during the intermissions,” he says. “But I would also be on the mic as a supplement, announcing people to come in. I would be offstage saying, ‘Judges, this is entry number 133 we’re welcoming.’”

At times, he questioned whether he had the resolve to make it as a musician. Between the funeral homes and dance competitions, much of his time was taken up trying to make ends meet.

___

“The hustle of just trying to afford being a musician, it made me question whether music was worth it,” he says, looking out of frame as if embarrassed by his former self-doubt. “Some of the jobs were fun, but I wasn’t finding a creative joy in that. I was trying to afford being a musician.”

At the same time, he was finding joy in Toronto’s lively club scene, where he would regularly DJ before beginning to write his own electronic music, which culminated in his full-length debut album, Babycasey.

Hearkening back to the manic, boy-band-obsessed music culture of the early aughts, Babycasey was Casey MQ at his campiest. Across 13 nostalgically titled tracks such as “U + Me 4ever,” “The First Song I Ever Wrote,” and “Child’s Stadium,” he celebrates the sound and styles of the pop culture that informed his childhood, all the while challenging its heteronormativity. On the album’s lead single, “Candyboy,” he takes the typically saccharine lyrical template laid out during the heyday of boy bands and puts it to his own purpose, using his trademark falsetto to sing about an imaginative safe space to explore same-sex adolescent desire. And on “Celebrity Crush,” over glitchy synths and up-tempo drums, he ironizes the clean-cut image of celebrity mythologization, speedily singing: “Celebrity crush I don’t think about in the evenings / In the daytime, in the nighttime, on a Wednesday, on a Friday, / When I cum on the weekend, my fingers on your famous body / I don’t touch myself thinking about // Leo, Justin, Bradley I love you.”

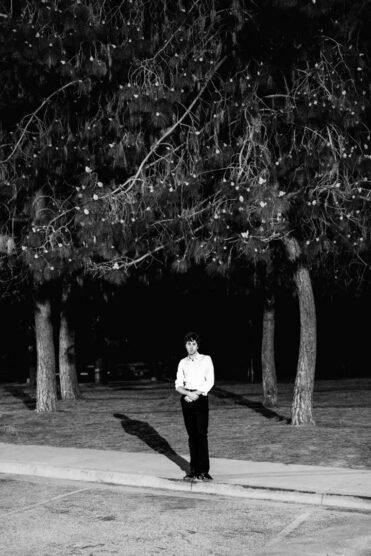

Casey MQ’s second album, Later That Day, the Day Before, or the Day Before That, out June 7 via Ghostly International, marks the start of a new musical chapter. A radical departure from the hyperpop-tinged Y2K nostalgia that coloured Babycasey, Later That Day sees him return to his roots, the synths often pared back in favour of the piano and clear lyrical composition replacing manic wails and declarative nonsequiturs. Drawing on musical influences as diverse as Joni Mitchell and Claude Debussy, there is an introspective maturity to Later That Day—while style is abundant, its elegance leaves room for the substance to occupy the foreground.

While the musical delivery of Later That Day veers quite drastically from Babycasey, the shift in philosophy and content is marked only by a small but significant change in perspective. Whereas before, Casey MQ crafted music around memories of his childhood, memory itself has now become his chosen topic. “Babeycasey is a memory album. It has that perspective of looking at it like a child and being a child and sort of trying to create a childhood,” he says. “This one [Later That Day], for me it was now ‘what is memory?’ And why was I trying to create a narrative that I actually can’t even really touch? Whenever we think about those past experiences, we’re making a change, we’re making a shift.”

Littered with unanswerable questions and statements of self-doubt, Later That Day is an opulent fever-dream that explores the ambiguity of memory via impressionist vignettes that bear only the slightest hint of a narrative. On “See You Later,” Casey MQ grapples with the impossibility of sharing his life apart from a lost love, singing: “How do I tell you? / I’ve lived a whole life / How do I tell you? / I’ve lived many times.” At points such as this, the inability to live in a shared memory takes on a melancholic tone, either the symptom or the cause of loneliness. But there’s also a sense of liberation in forgetting on Later That Day. On “Words for Love,” the literally unrememberable future becomes the North Star in a relationship riddled by uncertainty. “The fight for the future / What is unknown is the answer / I can’t tell you what love is / But I know that I felt it,” he sings.

Later That Day is also a paean to Toronto, the city he credits with his musical development and where the memories he uses as a frame took place. “Grey Gardens,” the album’s glittering, cinematic piano ballad opener, was inspired by a dream he had about the acclaimed restaurant in Toronto’s Kensington Market neighbourhood rather than the 1975 documentary of the same name. The song itself sounds as if it was recorded within the slowly dilapidating house from the documentary, its simple piano movements fluctuating in speed and his raspy voice struggling to fill the hollowed-out space. Grey Gardens the restaurant is also a cavernous space for Casey MQ—compared to Alice’s Wonderland, it is a means to explore the unnavigable depths of a shared memory. “Reach into me,” he implores on the song’s chorus, “Take everything / Remembering is not the opposite of forgetting / It’s like the lining.”

___

The way Casey MQ talks about the shift in his music, you get the sense that he would be just as comfortable working in any artistic medium, so long as he is able to explore the inner workings of his mind.

While he hasn’t yet explored any other medium in full, he has begun to devote more of his time to scoring films. “I started to find myself more pulled to it because I found it was connected with that ‘going into world’ type of thing.’ Like using art as performance,” he explains. After attending a Canadian Film Centre program that connects musicians with directors, screenwriters, and editors, he began scoring for Toronto-area filmmakers. One such project, “And Then We Don’t,” an original song he co-wrote for Canadian director Thyrone Tommy’s film Learn to Swim, earned him the award for Best Original Song at the Canadian Screen Awards.

At the same time as he began scoring films, Casey MQ also found himself increasingly in demand for his songwriting and production work. While these jobs are far more glamorous, both musically and monetarily, than the gigs performing at funeral homes and announcing at dance competitions, they are also more formative when it comes to his solo artistry. “I’ve realized that there’s a stark contrast between previous work [Babycasey] and this work [Later That Day]—it’s inside of the landscape of being an artist and being a performer and expressing myself in these various ways,” he says. Referring to his collaborations with artists like Cadence Weapon, Flume, Vagabon, and Empress Of, he says, “It’s intrinsic to how I want to be as an artist in my life, really.”

The artist that Casey MQ wants to be following the release of his latest album is one that tours, something he wasn’t able to do with his first album due to pandemic restrictions. It feels like a full-circle moment for the ascendant songster. Whereas he once made music that was pointedly digital, Later That Day feels more cinematic and deserving of a larger stage. However, it is also a project on which a hint of his past nevertheless peeks through. On “Me, I Think I Found It,” a James Blake-esque love song that forms the emotional core of the Later That Day, he explores how the digital world informs real life love, crooning: “Me, I think I found it / Pillow face and pixel eyes / Me, I think I found it / Screenshot the perfect smile / Me, I think I found it / Digital imagination.” As with the album as a whole, the beauty of the song rests in its uncertainty, and the almost heroically resplendent soundscape that frames its repeated half-knowing claims. It may be a love song or it may be about Casey MQ discovering his voice as a musician—as always, it’s up for interpretation. Luckily, when it comes to a project as ambitious, profound, and downright sonically stunning as Later That Day, there are no wrong answers.