-

Rachel Feinstein at her studio in New York.

-

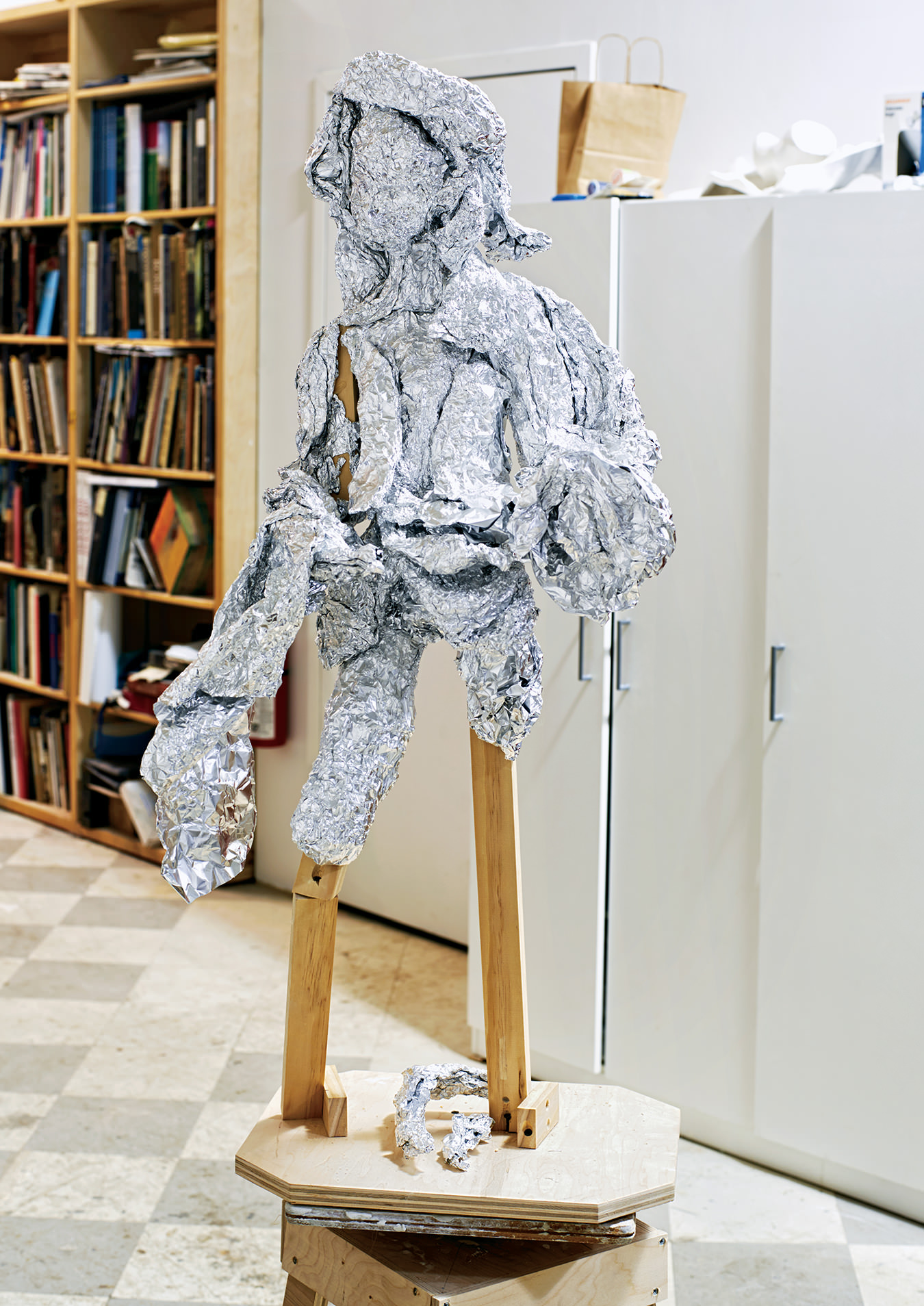

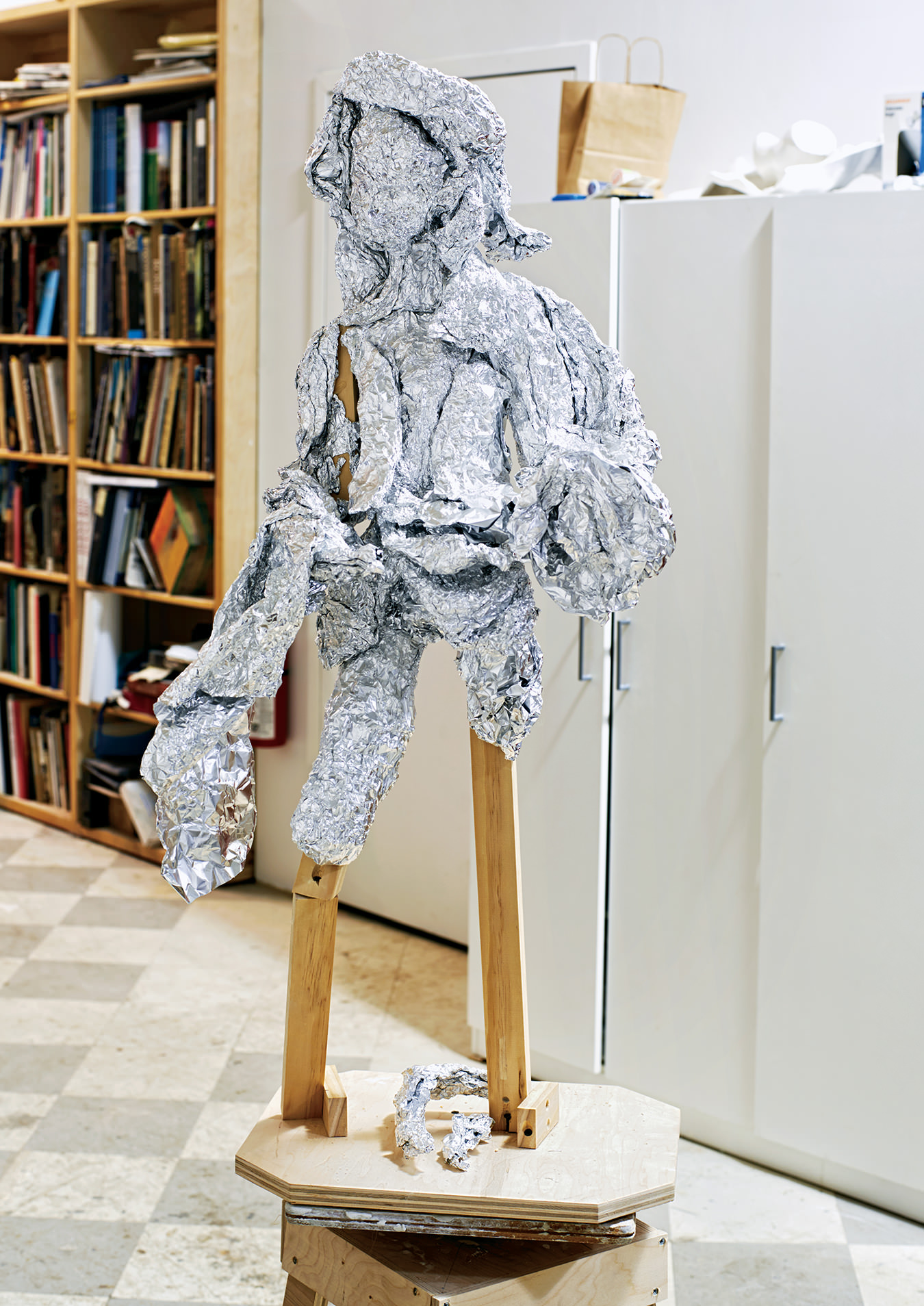

Artworks in progress at Rachel Feinstein’s New York studio.

-

-

-

-

-

Rachel Feinstein

Fantastical art.

The bright, white Tribeca space of Rachel Feinstein’s studio is clean and organized, packed with books, notes, and massive sculptures. There’s also a puppy that jumps onto Feinstein’s lap and contentedly passes out. “This is Mr. Green Jeans,” she introduces. With her wavy hair pulled back, Feinstein exudes wisdom and strength, but also an innocence and openness that belies her 43 years.

She and her husband, artist John Currin, are considered a power couple of the New York art scene. Feinstein met Currin at the peak of her wild days, when she was fresh out of Columbia University School of the Arts and already quite successful (thanks, she says, to her teachers and mentors putting her work in shows). He was 32. She was 23, immersed in the aggressive, in-your-face feminism of the eighties (think Kiki Smith, Sue Williams, and Madonna). “I would wear a see-through dress, and put a big fake black pubic wig on that would have hair coming out from my underwear, and I did casts of my vagina and [would] wear it as jewellery, and wear drop earrings that were casts of my anus,” she says. “The funny thing is, there was a part of me that was that way, and a part of me that wasn’t that way. When I met John, I kind of let that all go because it took so much energy to be that person, and I wanted to put that energy into sculptures and objects, versus myself as the sculpture.” Two decades and three kids later, they’re both enjoying thriving careers.

Artworks in progress at Rachel Feinstein’s New York studio.

Feinstein’s creative curiosity seems to extend beyond herself, her family, even her art, and deep into the interconnectedness that links us all. Between past and present, fact and fiction, imagination and reality, and into the murky zones of consciousness and imagination. One might say it’s all about layers—the many different realities within a piece of art, and within a person—and the delicious process of unearthing each one.

“That’s why I loved showing in Rome,” she says of her eponymous 2012 Gagosian Gallery show. “You literally are making art on top of layers of other buildings that have been there for a thousand years. It’s just amazing. I made seven [mirrored] panels of this continuous panorama of a made-up Rome that I painted here, and then we made it into mirrored wallpaper, full scale, to go around this entire oval room.”

Before the Rome exhibition there was her 2011 Lever House Art Collection installation (inspired by “The Snow Queen” fairy tale), and just after, the excitement of designing and building the 9-by-18-metre sets for Marc Jacobs’s fall/winter 2012 fashion show (on which teams of more than 50 carpenters worked 24 hours a day for 10 days); and then there was her 2014 sculpture Konchakovna, at the Metropolitan Opera’s Schwartz Gallery Met as part of the Imaginary Portraits: Prince Igor group exhibition, and her most recent coup, an outdoor public sculpture installation in New York’s historic Madison Square Park—Feinstein’s fascination with fantasy, fairy tale, and theatrical settings is quite a contrast from the minimalist aesthetic that’s popular in today’s contemporary art world.

Feinstein and Currin share a passion for the Old Masters, the baroque, and the Gothic, which she initially learned from him. “I haven’t been to a Chelsea gallery in, like, 12 years,” she says. “I just go to the Met, to the Frick, to the Guggenheim sometimes. So I’ve gotten a great vocabulary of all the old Gothic sculptors, and [Gian Lorenzo] Bernini, and I know more about that stuff than most contemporary sculptors. But sometimes it makes me feel like an old fuddy-duddy, and not being in touch with my generation.”

Represented by Marianne Boesky Gallery (a solo show is planned for next winter), Feinstein and her creative tunnel-vision have produced a unique and highly acclaimed body of work that bridges the worlds of fantasy, iconography, magic, and decay. Folly, which opened May 7 in Madison Square Park and continues through September 7, takes these layers of reality to new depths. Three large-scale white aluminum sculptures or “follies” are installed throughout the park: a rococo hut, a house on a cliff, and a flying ship stuck in a tree. At once powerful and fragile, these delicate-looking structures feel as though they’ve been kidnapped from a fairy tale, all graceful lines and lyrical details that invite the public to dive into this in-between wonderland.

“They really are fantasy little huts that are purely non-functional,” says Feinstein, pulling up on her iPad 3-D images of the allegorical pieces, which she first conceived as tiny paper drawings in her studio—and which now measure between eight and 26 feet tall. “That’s what a folly is, you know? Originally, we were thinking about having people populate all these little beautiful villages, but I realized that real people are going to be the people populating the villages.”

And so, New York assumes the role of set, and passersby are characters. As the real world—the world of New York, no less—collides with her fantasy one, Feinstein is fascinated by the clash and alchemy of these different realities. Indeed, it inspires us to question our own concepts of reality and, perhaps, the roles we play within our own worlds.

“It’s the weird thing of the fakeness of the set,” she explains. “It’s like going to Disney World and having this thing displayed that you identify with—like, this is what it is, but then, it really isn’t this thing. It’s a fantasy placed into our own reality.” She points out, “How can you get more real than a park within the Flatiron District? There’s all this history, and I can put these props up—strange ruins in this place that has the layers of other people on top of it.”

It comes as no surprise to learn that cinema, particularly the directors Fellini and Kubrick, are among Feinstein’s inspirations. “I just love the idea of different realities imposed on you,” she says. “I love 2001—the last scene where the guy’s in this room, and he’s dying, and the floor’s like a 1970s disco floor, but then there’s like rococo plasterwork. The combination of all these layers of different times—it’s space and it’s death, this infinity of not knowing what’s happening. I’m interested in ruins, and certain iconography—things that mean something to different people. Rococo to Americans is Liberace, but it’s also Disney World, it’s ‘Sleeping Beauty’—this Grimms’ fairy tale, Black Forest aspect of stuff.”

Consistent with this theme of layers, a significant element of Feinstein’s current work is the display of the nuts and bolts behind these fantasy creations—the figurative person-behind-the-curtain. “I like that you have the three-dimensionality of the castle in front of you, but if you walk [around], you’ll see the sub-structure,” she says.

Certainly, from the viewer’s standpoint, seeing the “little pieces of wood holding the whole thing up from behind” causes one to ponder the subjectivity and fragility of what, at the surface, seems so solid—be it society, relationships, or even life itself. This is the stuff not only of layers of consciousness but also of archetype, myth, legend, and religious iconography, all of which have served as Feinstein’s gracious muses as she creates her colliding worlds.

Archetype, myth, legend, and religious iconography have all served as Feinstein’s gracious muses as she creates her colliding worlds.

Surveying the scene within Feinstein’s long, narrow studio space are several large, 3-D sculptures, exquisite from every angle, no matter where you might find yourself standing. There’s a nine-foot-tall woman made from wood, her body all curves and movement, two concave valleys in her chest. “That’s Agatha,” Feinstein says of her sculpture, which was part of the aforementioned Rome exhibition. (Saint Agatha was a virgin martyr remembered for her resistance.) “She was killed by having her breasts cut off, so that’s why she has the holes in her breasts.”

Born and raised in Miami—being a tall, pale artsy type, she stood out—Feinstein always wanted to be an artist. Her grandmother would pick her up from school and shuttle her to drawing, painting, and sculpture lessons. “My father’s a doctor, my mother’s a nurse, and my sister’s a veterinarian,” she says. Her father is a Brooklyn Jew, her mother an Irish Catholic. They met in college, and it was love at first sight. “I grew up in a house where visuals did not matter. They would buy all their furniture from Rooms To Go. It was nice stuff, but it wasn’t this obsession over everything has to be beautiful—where if you’re a visual person, you are aware.”

Aware, certainly—not only of the beauty of fine art but also of more common cultural icons.

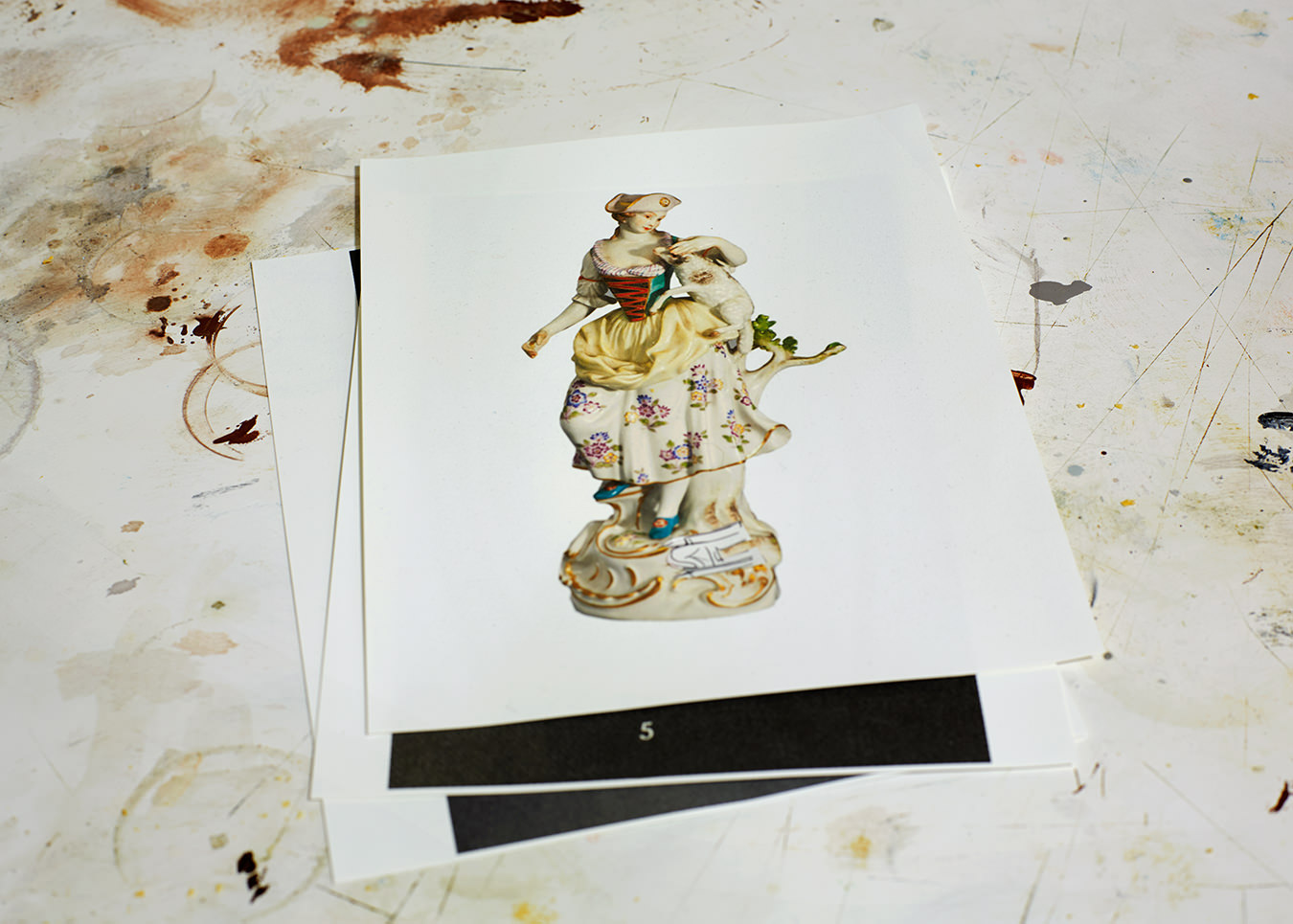

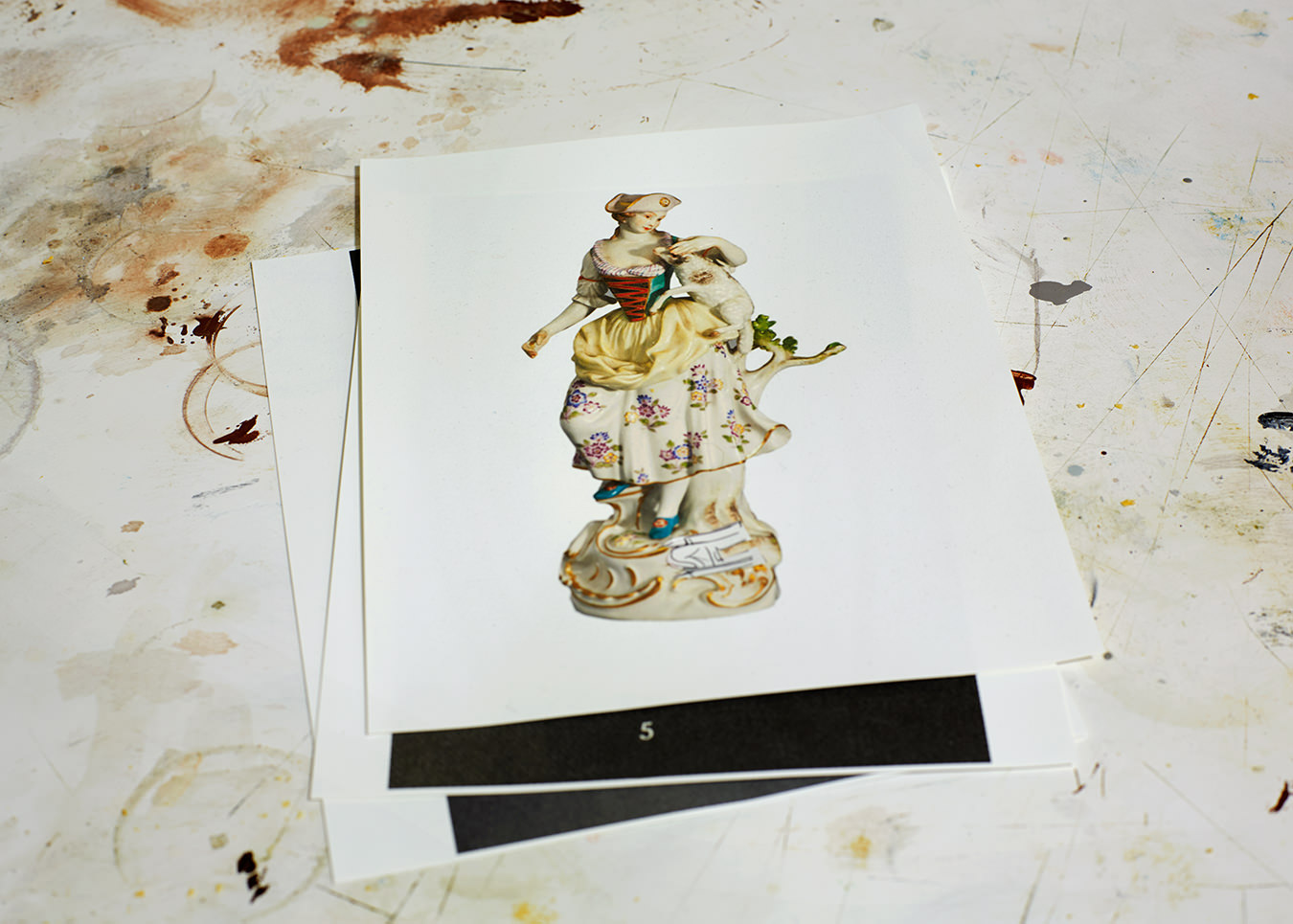

Funnily enough, the initial spark behind Feinstein’s wave of graceful, kinetic sculptures was nothing holier than the humble porcelain figurine. “They’re so colourful and very pretty, and I liked the subversive aspect of them being considered kitsch, and that old women on the Upper East Side are the only ones who like them,” she explains.

Regarding her process, she says, “I do the drawing, then I scan the drawing before I cut it up, then I end up just free-floating the making of these things in three-dimensional. The problem with that is, as I’m making them, I’ll make up new pieces that aren’t in the drawings, so it’s a little bit confusing, because then I have to go back and rescan all the [new] pieces.”

To make Folly’s sculptures, Feinstein worked with a fabricator whose team used the Rhinoceros 3D software program to build the structures architecturally after the various pieces had been cut. “So then the fabricator literally has to just put it together. It’s basically being built like a real house would be built,” she says. “It’s a whole new way of doing it. It’s the first time I’ve ever done it this way.”

Feinstein is hyper-focused on each and every step, and her approach to her work (after she’s developed the broad strokes of a concept or piece) is extremely detail-oriented. Yet before giving birth to their first child at 32, Feinstein says she wasn’t obsessive—on the contrary. “I was a mess,” she says, laughing. “I would sleep till 11, have breakfast at 1, get to my studio at 3 and work till midnight or 1, and have dinner at 2 in the morning. That was my life.” Today, she says, “I think now I’ve gotten to be good at [motherhood], but it didn’t naturally work with my personality—because it’s all about scheduling, and things that kids need.”

Certainly she loves being a mom, and she’s devoted to her family. But Feinstein feels her career might just be beginning. “I have a very strong feeling that women artists do get better with age, and they become successful with age. [French-American sculptor] Louise Bourgeois, all the big ones, came about postmenopausal. I think you have to get the veil of reproduction out of your system to be able to compete with the men. Because you’re no longer a slave to your period and thinking about having kids. By the time you reach your early 50s, you’re like, ‘Okay, that’s over and done with, now let’s get our nose to the grindstone.’ I’ve talked to other female artists that have gone through that and they say it definitely happens to them.”

Ultimately, though, within the intertwined worlds of Feinstein’s art and life, what better discovery could there be than to unearth the layers of her own childhood? “Having children brought me back to that beginning of making things, which goes back to my belief that childhood is where you form everything for the rest of your life,” she explains. “When I was eight, I would sit in my closet and just make things. I was always by myself and always involved in creating, and [to make art] you have to go back to that original feeling.”