-

The Aquariva by Marc Newson was unveiled in 2010.

-

The enchanting scenery of Portofino, Italy, where Riva boats are a staple.

-

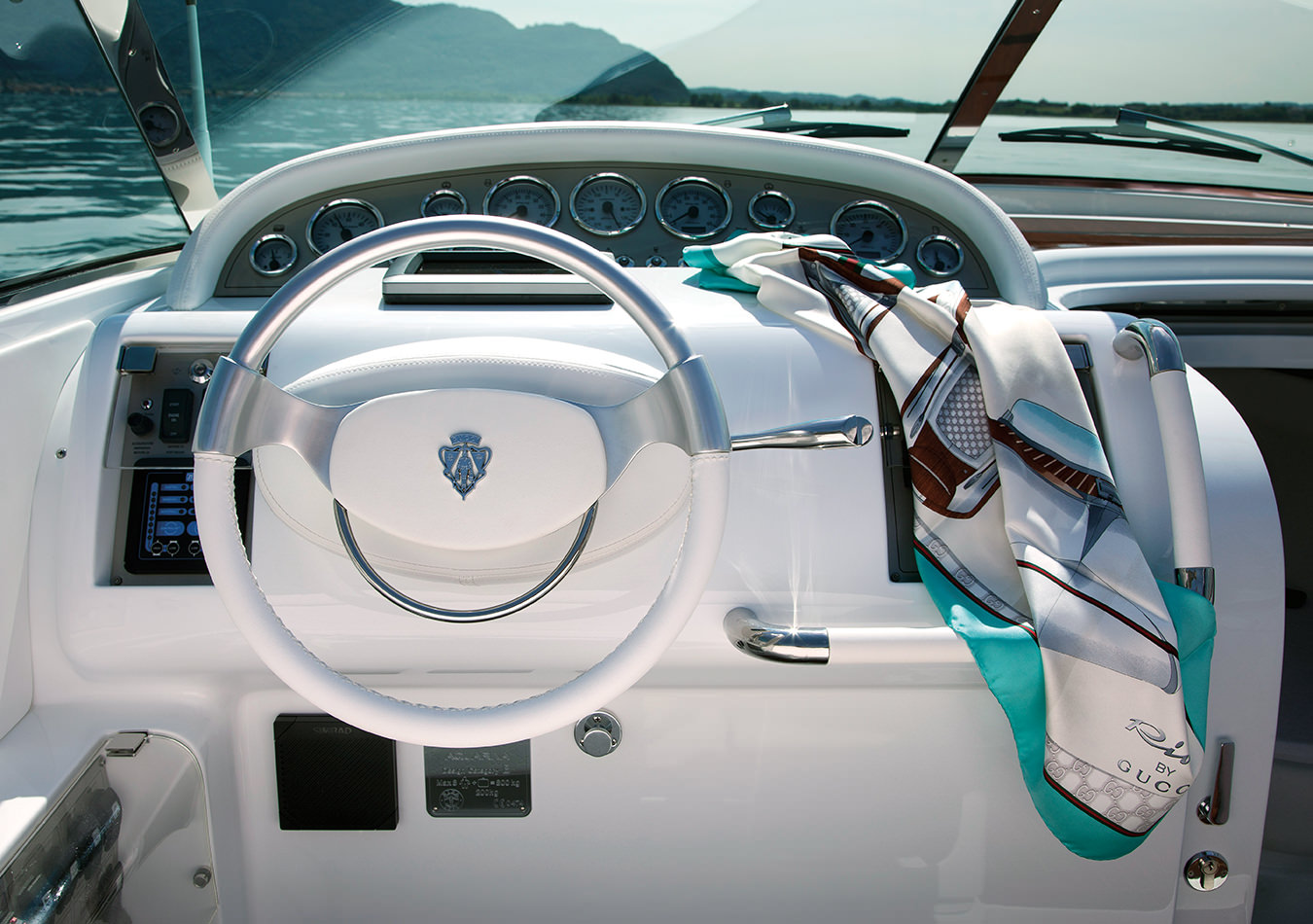

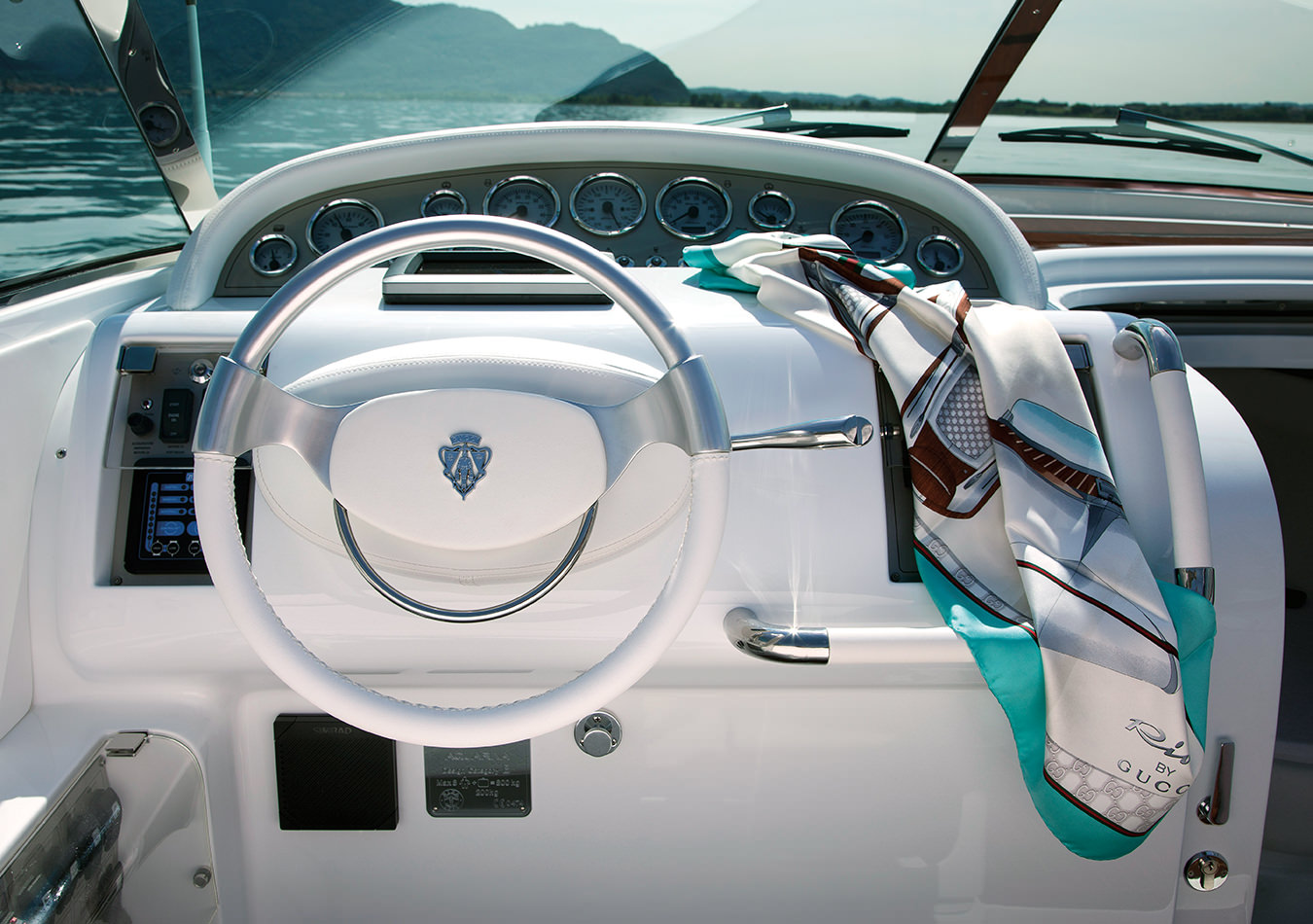

The Aquariva customized by Gucci creative director Frida Giannini.

-

The elegant interior of a Rivarama.

Riva Yachts

The legend continues.

In an age when luxury brands make much of building emotion and stories around their products, Riva has the kind of history and the deep emotional power that are worth untold millions of marketing dollars. Its status as a legend is far from hyperbole; the name is right up there with Rolls-Royce, Ferrari, Fabergé, and Cartier. Indeed, in the same way that Savile Row is shorthand for a set of codes that, along with defining bespoke suits, suggest the kind of people who would wear them and the way of life they might lead, Riva is instantly understood to mean more than just a boat.

Riva is a racy, heady cocktail of glamour laced with a touch of nostalgia for those days when being a member of the jet set meant something really special. It’s the golden age of the French Riviera—Monte Carlo, Cannes, Saint-Tropez, Portofino. It’s princes, playboys, and players—Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, Gianni Agnelli, Prince Rainier III and Princess Grace of Monaco, the Aga Khan, Brigitte Bardot, Sophia Loren, Gunter Sachs. In short, it is la dolce vita wrapped up in nine-odd metres of highly polished mahogany.

Given its somewhat rakish connotations, it is no surprise that Riva’s boats have featured in the original version of The Italian Job and in several Bond films; in Ocean’s Twelve, Clooney, Pitt, Damon, and company zipped around Lake Como in a Riva boat.

The Aquariva customized by Gucci creative director Frida Giannini.

Riva’s history dates back to 1842, when Pietro Riva established a small boatyard in Sarnico, on Lake Iseo, turning his skills from boat repair to building boats for the lake’s fishermen. Each subsequent generation made great strides and expanded the business: Pietro’s son Ernesto introduced the internal combustion engine in 1880; third-generation Serafino began designing boats for speed, breaking many motorboat-racing records and thus spreading Riva’s reputation well beyond the lake’s shores. But it was one man, one boat, and one decade that catapulted Riva to the status of 20th-century cultural icon. The decade was the 1960s, the boat was the Riva Aquarama, and the man was Carlo Riva, fourth-generation scion of the family.

In 1950, after taking over what was a financially precarious business, Carlo Riva decided to focus on series production of pleasure boats; this would optimize production costs while still harnessing the shipyard’s exceptional handcrafting skills. Fascinated by American boats, he took inspiration from Chris-Craft’s production methods, which at the time dominated the market for high-end runabouts on both sides of the Atlantic. In 1951, he began buying engines from Chris-Craft, believing that postwar Italy was producing nothing of the requisite quality.

But first, Carlo had to sell some boats. He knew that extremely high quality and distinctive design were not optional, and said that he was prepared to “risk everything if necessary” to expand the company—including his business relationship with his father. An overly traditional man, Serafino, Carlo’s father, resisted his son’s ambitious ideas. Carlo persevered and bought out the yard (supported by advance payment for a new boat from the Beretta family, of firearms fame, who were neighbours of Riva on Lake Iseo), and immediately and strategically doubled the price of his racing boats, which were not very profitable, to deter his father’s old clients. The gamble worked.

Riva’s history dates back to 1842, when Pietro Riva established a small boatyard in Sarnico, on Lake Iseo.

Key design cues for the new generation of boats came from the two-seater Riva Corsaro, introduced in 1946: based on the concept of a “water-borne sports car”, it had an automotive-style dashboard and steering wheel, and its streamlined flanks wrapped over the bulkheads—design codes that became inseparable from the Riva name. Two new models, Riva Tritone and Riva Ariston, were shown at the 1950 Milan Trade Fair, where Carlo rented a booth on credit and stayed overnight in the attic of a convent to save money. (With his innate understanding of the power of image, he arranged meetings in front of the city’s smartest hotels, always sure to arrive first.)

A year later, the first true series-production boat, the Riva Sebino, was introduced, followed by the larger Riva Florida; movie appearances followed, among them Mambo and Some Like It Hot. The brand was well on its way, enhanced by Carlo’s grasp of image and branding: even the delivery trucks had chromed hubcaps and were painted in the company’s two-tone turquoise and white; the drivers—like the shipyard workers—wore white overalls with the distinctive “handwritten” logo embroidered in corporate blue.

Still Carlo was not satisfied. Obsessive about detail, he was deeply involved in everything: styling and design, engineering, buying materials from suppliers, every stage of fabrication—even casting the patterns for the metal fittings. When the company outgrew its original boatyard, Carlo designed new premises a little farther along the Sarnico shore, which opened in 1954. He laid out the production sheds to combine efficiency with stage-by-stage quality control, and designed his own office, still in existence: perched on steel stilts above the concrete jetty and resembling a ship’s bridge, it has a row of rounded windows facing the lake, and internal windows with a direct view into the production sheds. Thus, just a couple of strides from his desk, Carlo had a birds-eye view of the craftsmen at work. For him, paying constant attention was crucial. “My boats must be perfect,” he said. “Anything less would ruin my name.”

In 1962, at the International Nautical Fair in Milan, Riva presented the prototype for what many people considered to be that perfect boat: the Aquarama. A synthesis of all the wooden power cruisers he had developed since 1950, it was harmonious and elegant—a triumph of form following function. But not only was it a thing of great beauty and immaculate build quality, it was a technical tour de force: its specially tuned twin V8 engines propelled it to 70 kilometres an hour, and its ride was entirely balanced.

When the first Aquarama reached the Mediterranean Sea, Carlo—ever the showman—made a bet with his client Gianni Agnelli (the founder of FIAT), who said that the boat looked as if it could be unstable at high speed. Carlo told him to drive it as hard as he could, and if he managed to turn it over, he could have it for free. Agnelli lost the bet, and soon Riva had a queue of tycoons, stars, heads of state, and ordinary not-quite-millionaires buying. No matter the purchaser, Carlo made it a policy that a boat was to be paid in full before delivery.

“My clients are paying for quality, not luxury,” Carlo insisted. For him, that meant not just an average of 3,000 hours of work (the range is from 2,000 to 9,000 hours for each boat) from the laying of the hull to the final coat of mirror-smooth varnish, but also keeping a store of 283 cubic metres of mahogany (which he seasoned for four years before use), building his own plating factory, and, when he introduced the signature lobster-coloured upholstery fabric for the Aquarama in the 1960s, having 3,000 metres of it dyed in a single batch to ensure consistency. It’s little wonder that a Riva cost at least 20 to 30 per cent more than any similar boat—and that being photographed on a Riva secured one’s image as a member of the smart set.

But the glory days were not to last. As the 1960s ended, labour strife throughout Europe infiltrated even the Sarnico shipyard, while the advent of fibreglass threatened to do to boat building what quartz movements did to the fine watchmaking business. Disillusioned, Carlo sold the business to the American company Whittaker, together with his naming rights.

The company’s transition to fibreglass was not a happy one, and a move to larger boats diluted Riva’s identity even further. Although the power of the name continued to draw customers, for the next three decades—even including a period under Rolls-Royce ownership throughout most of the 1990s—it floundered. Carlo Riva could only watch, sadly, from the sidelines, until, in 2000, the Ferretti Group acquired the business. For Norberto Ferretti, it was clear that Riva’s DNA was its greatest asset, and returning to the thread established by the Aquarama and its 1960s peers was the key to its future. He briefed Mauro Micheli (who, through his studio, Officina Italiana Design, has been Riva’s sole designer since 1994) to reinvent those Riva codes for the 21st century.

In 2001, the Aquariva was unveiled, and its success made clear that the power of Carlo Riva’s original vision was undimmed. At just over 10 metres long, with a fibreglass hull, mahogany topsides, a traditional washboard deck, and a chrome-rimmed split windscreen, it paid homage to Carlo’s eye for detail, and at 42 knots, it gave a nod to Serafino Riva’s racing prowess.

“We wanted to create a sophisticated runabout, ideal for both lake and sea, that meets all the requirements of comfort … distinguished by her unmistakable design, stirring emotions, and to be appreciated not only by nautical enthusiasts,” said Mauro Micheli. He could just as well have been describing the Aquarama.

The 13.4-metre Rivarama was launched the following year, cementing Riva’s new direction. It was named the best boat of 2002 by Boat International magazine, and again in 2003; in 2004, it was named one of the most beautiful boats of all time by Motor Boat & Yachting magazine. In first place? The original Aquarama.

Riva is a racy, heady cocktail of glamour laced with a touch of nostalgia for those days when being a member of the jet set meant something really special.

With the new direction—innovation combined with instantly recognizable homage to the brand’s traditions—firmly established, and Carlo Riva welcomed back to the shipyard as a de facto ambassador and éminence grise, the company launched a series of larger boats (the 68’ Ego Super, Rivale, 63’ Vertigo, and 85’ Opera Super), all of them more successful in capturing the essence of Riva than any of the boats from the 1970s to the ’90s.

“We love a classical, essential, clean design style, where the keyword is remove, not add,” said Micheli. “Our aim is to achieve the essence of a unique, unmistakable style, where innovation meets and develops in harmony with a tradition that has become legendary.” In 2006, the hundredth Aquariva left the shipyard in a commemorative limited edition called Aquariva Cento. (The hundredth Rivarama will come off the line this year.) Sensing the extra value placed by buyers on special editions, Aquariva by Gucci was unveiled in 2010.

Customized by Gucci creative director Frida Giannini, with a white hull and the brand’s distinctive red and green stripes at the waterline, it celebrated the fashion house’s 90th birthday. (Gucci is only a year older than the still-spry Carlo Riva, who celebrated his own 90th with the entire shipyard family this February. And, note, family is no corporate platitude; many employees are the third generation of their family to work at Riva.)

Also in 2010, the celebrated industrial designer Marc Newson was commissioned to design a special-edition Aquariva. Not so unusual, perhaps—except that, instead of being unveiled at a boat show, it was presented by Larry Gagosian at his eponymous Manhattan gallery on West 21st Street, thus according Riva’s new status as works of art.

For Newson, the opportunity to reinterpret the Aquarama iconography “seemed like a no-brainer to do.” The romance got his juices flowing, he says. “I was aware of Riva even as a child growing up in Australia … If you had asked me when I was 15 what is the most famous and beautiful boat in the world, I would have said, without hesitation, the Riva Aquarama.”

Last spring, at the Cannes Boat Show, Riva’s newest baby, the Iseo, was unveiled. Baby it was, at just eight metres long, nestled behind a lineup of Riva’s bigger, grander boats—and yet its presence belied its size. It captures the indefinable “Riva-ness” of its 1960s ancestors without the faintest trace of retro or nostalgia. The engine is hybrid and in every detail it’s a Riva: the mirror-varnished woodwork, the judicious touches of chrome, the leather work, the quality, and the lines—that flared bow and the signature downward sweep of the stern.

In a shed at the Sarnico yard, half a dozen Iseos in various stages of construction are perched on low metal cradles, looking like beautiful flightless birds. Here, it’s easy to see the Riva quality at every turn: a worker dusting down a hull with paper tissues, despite the fact that it is barely half-finished; the 40-millimetre foam core in the bulkheads of the Rivarama (32 millimetres is “normal” high quality); the carpenter hand-sanding a mahogany deck section—stroking might be a more accurate word, so gentle are his movements. In another shed, there’s a new model that will be unveiled later this summer: the Riva 63’ Virtus open. Elegant and smooth-lined, its subtly metallic fiberglass hull is the epitome of modernism.

The global financial crash, which coincided with a period of major acquisitions, led to the debt-laden Ferretti Group being bought this January by a Chinese conglomerate, and the question is inevitable: Will any of this be compromised? Time will tell. The consequences of poorly judged decision-making have been proved before.

Everywhere in the workshops, Carlo Riva’s signature is writ large: wooden work benches and tool cabinets painted in the signature Riva turquoise; the wide concrete-floored corridor down which so many boats have passed over the years, on the way to the darsena (a small enclosed dock where the first in-water test was done), its walls painted in the classic turquoise-and-white stripes.

Carlo’s office, while also known as la plancia (the bridge), will forever be “Carlo Riva’s office”, say staff, and it remains virtually unchanged since he ran the business: the polished timber floor glowing in the reflected light from the lake; Carlo’s huge, curved mahogany desk and black leather chair; the black-upholstered banquette stretching the entire length of the window wall, where so many great names of 20th-century culture, power, and politics have sat. Its atmosphere is heady with the power of the Riva legend and the man who created it. The Aquarama is celebrating its 50th birthday this year—buon compleanno.