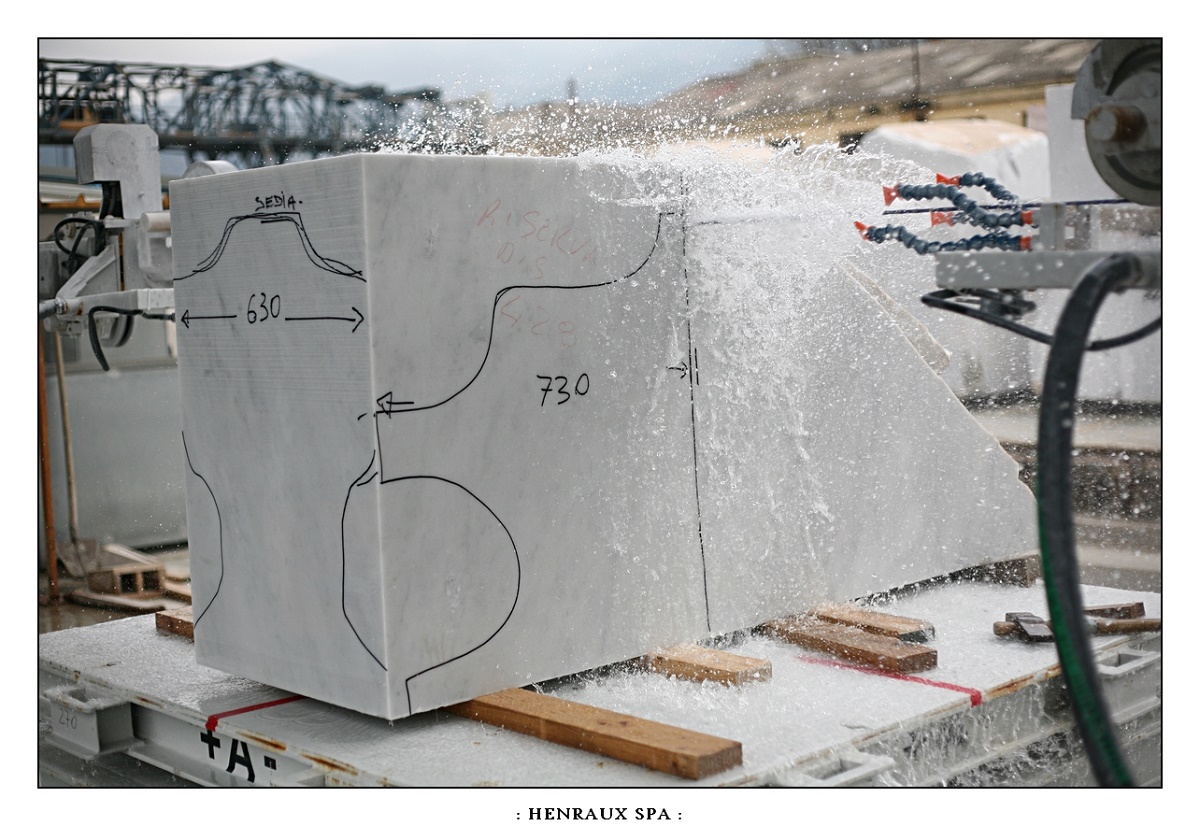

Photo courtesy of Henraux.

The Art of Nature: From the Quarries of Henraux

The Apuan Alps, a mountain range in Tuscany’s Massa Carrara and Lucca regions, is where marble is extracted and where artists, sculptors, and designers find inspiration and materials to work with. It is also the place, specifically the quarries of Henraux, where Michelangelo sourced his marble.

The ancient Romans used precious marble to pay homage to the deeds of the emperors. Michelangelo Buonarroti shaped marble as it if were living matter to create his great masterpieces. Contemporary masters Henry Moore, Jean (Hans) Arp, and Isamu Noguchi chose marble for their impressive projects. Although centuries apart, Michelangelo, Moore, Arp, and Noguchi extracted marble—a stone that embodies delicacy and strength—from the same place: the quarries of Henraux in the Apuan Alps in Tuscany’s Massa Carrara and Lucca regions.

Carrara is known the world over as the city of marble. In the 16th century, the Medicis commissioned Michelangelo to cover the façade of San Lorenzo church. “He [Michelangelo] arrives in 1517 and finds a virgin mountain, never excavated,” recounts Paolo Carli, president of Henraux. The Renaissance artist is said to have described the experience as the worst years of his life.

Transporting the marble down to the valley required arduous labour. Blocks of marble strapped in rope were pushed and pulled (a method known as lizzatura, now abandoned) to reach the port soon to be called Forte dei Marmi. After a few years, Michelangelo was called to Rome by Pope Leo X to complete the Sistine Chapel—the façade of the church was never completed and the quarry forsaken.

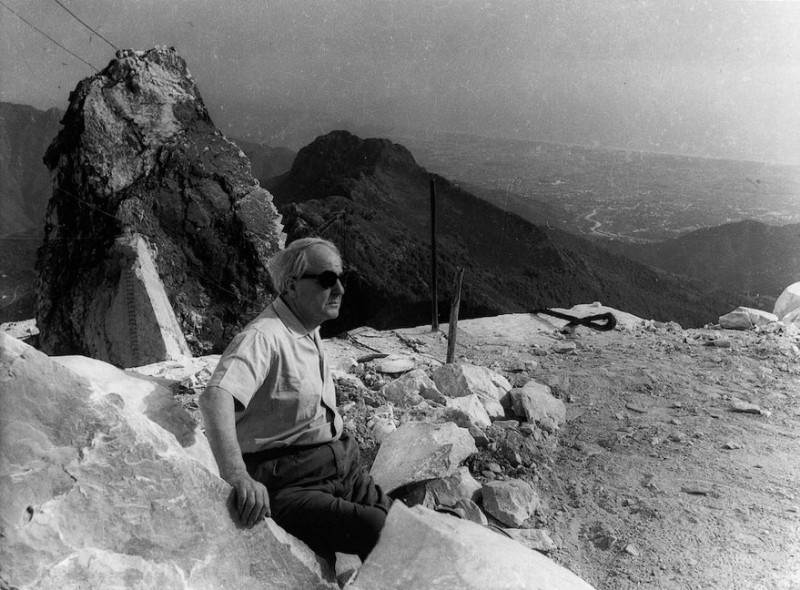

Henry Moore visiting the Henraux quarry, circa 1957.

In 1821, Jean Baptiste Alexandre Henraux took control of the quarry with Napoleon’s troops in the quest to find marble for the Napoleonic Empire. After Napoleon’s fall, Henraux became a private empire, with the company’s first major order from the czar of Russia for the construction of Saint Isaac’s Cathedral in Saint Petersburg. Soon after, Auguste Rodin became a frequent visitor to the Henraux quarries. “The uniqueness of the grain of our marble, with its compactness, makes it very durable, and its uniform grain makes for a crystalline finish,” Carli says. It goes without saying that the quarry where Michelangelo sourced makes for stone of desirability and distinction.

There is a special aura in the peaks of Carrara that connects its people to the territory and to the stone. The quarrymen speak of “cultivation” rather than “extraction” of marble to highlight the human role in the process. Despite modern technology, their work is an exercise in struggle and sacrifice. “Undoubtedly there is a passion that is involved in this daily work,” Carli says. “It is a difficult job, constantly in the face of the elements, and takes great mental and physical preparation to resist the harsh conditions.” A documentary series called Uomini di Pietra (Men of Stone), now in its second season, highlights the challenges, where the story of strength and prowess is on display, a tradition of working the quarry handed down from father to son.

Marble is very much associated with the Old World, but in the 1950s, then administrator of Henraux Erminio Cidonio decided to move beyond classical production and cross-pollinate with the modern era. In 1957, Henry Moore visited Henraux, commissioned to sculpt Reclining Figure for the UNESCO headquarters in Paris. “He [Moore] would eat minestrone, a steak, and drink Chianti even though he preferred to eat with whisky,” recounts Franco Pierotti, director of the Altissimo quarry. “Then I used to pick up ricotta cheese wrapped in beech twigs from the shepherds, on which he poured coffee and whisky and ate it as if it were a dessert.” Following suit, Henraux became the main reference for sculptors Arp, Noguchi, Joan Miró, and Georges Vantongerloo.

The industry has not escaped criticism, with environmental groups stating that quarrying has been “ruinously thorough.” No matter what side you are on, the place commands admiration. The marble mountains are a surreal landscape, shaped by geometries of vertical and horizonal planes. The rock reminds not only of the force of nature, but also the force of man as marble is sliced by machines. “We respect nature and the mountains and extract only what we need,” Carli, says, noting, “everything that we dig is directed to a project.” Henraux exports 85 per cent of its materials, present in many builds around the world including myriad New York skyscrapers, swanky hotels in Miami, London, and Monte Carlo, the Dubai International Airport, the Kuwait National Museum, and the Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque in Abu Dhabi. Last year, Henraux had a turnover of 32.5 million euros ($41.5 million CAD).

Henraux continues to diversify its offering across the disciplines of architecture, art, and design. Henraux 1821 is the parent company, which develops large-scale architectural builds. Luce di Carrara is the niche brand for industrial design (furnishings, interiors, and objects). Most recently, Fondazione Henraux, an initiative aimed at promoting marble in the visual arts, has set up an international sculpture award to promote the use of marble in contemporary art.

Much has changed since the time of Michelangelo, but the centuries-old quarries continue to be on the cutting edge.