-

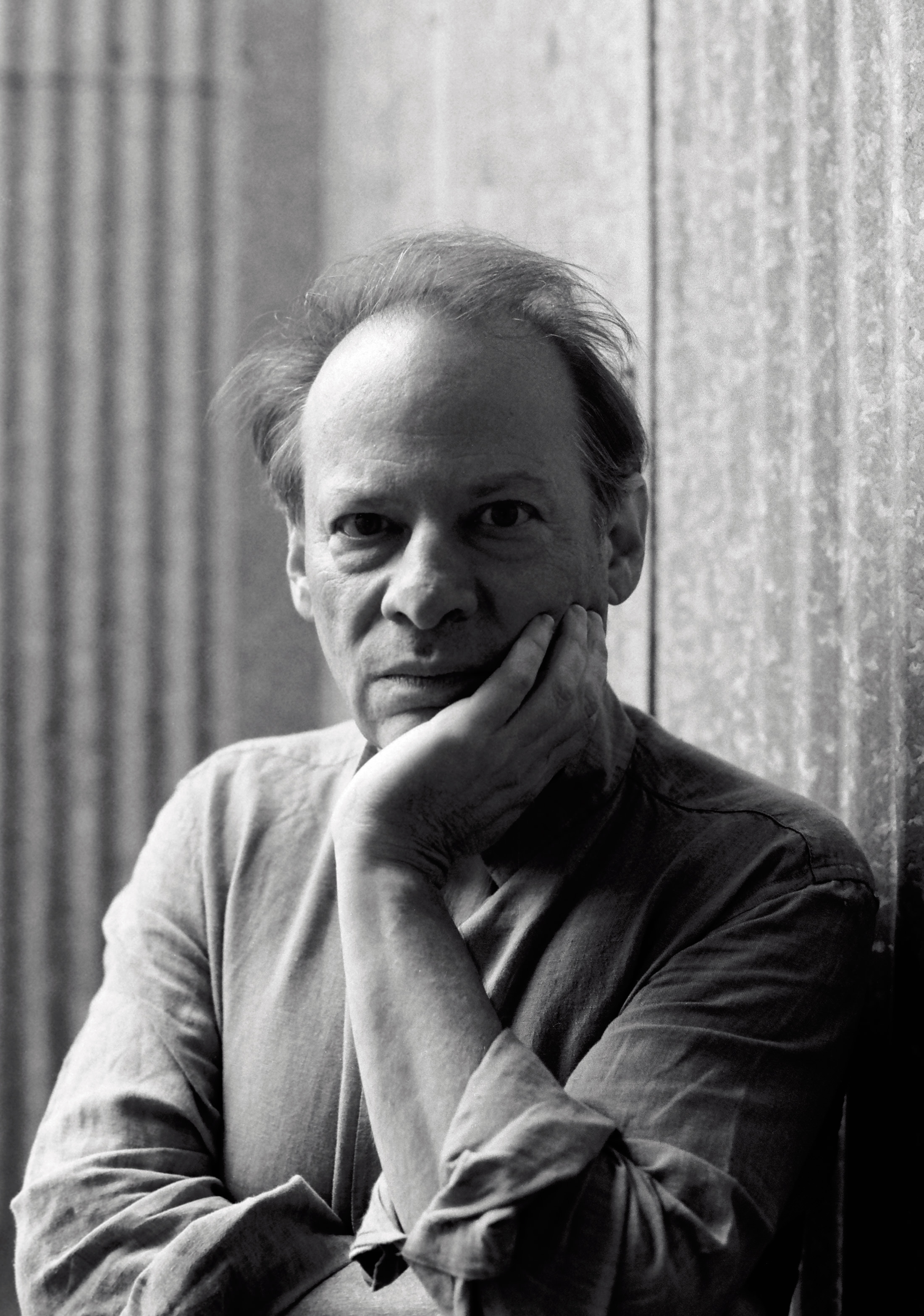

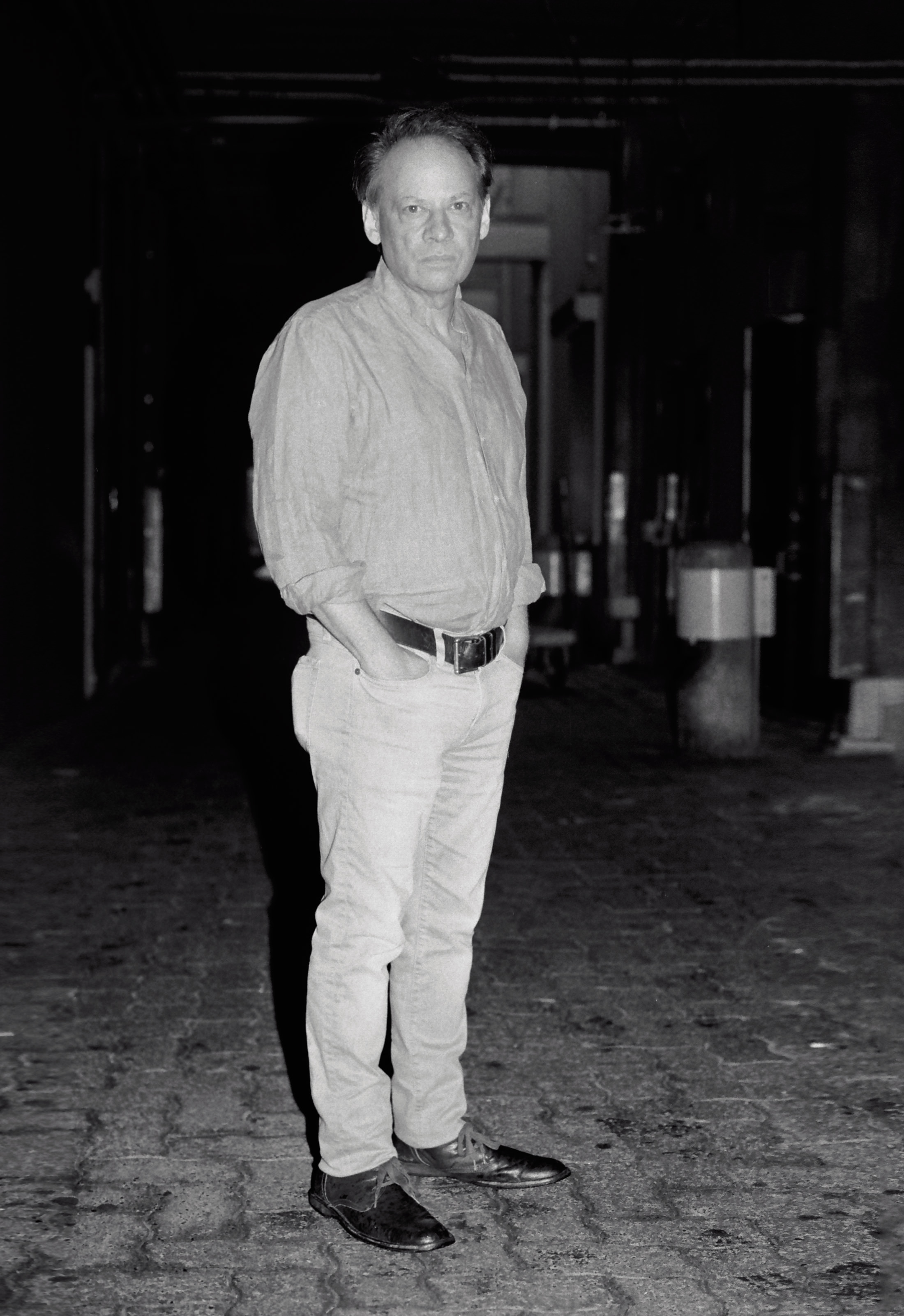

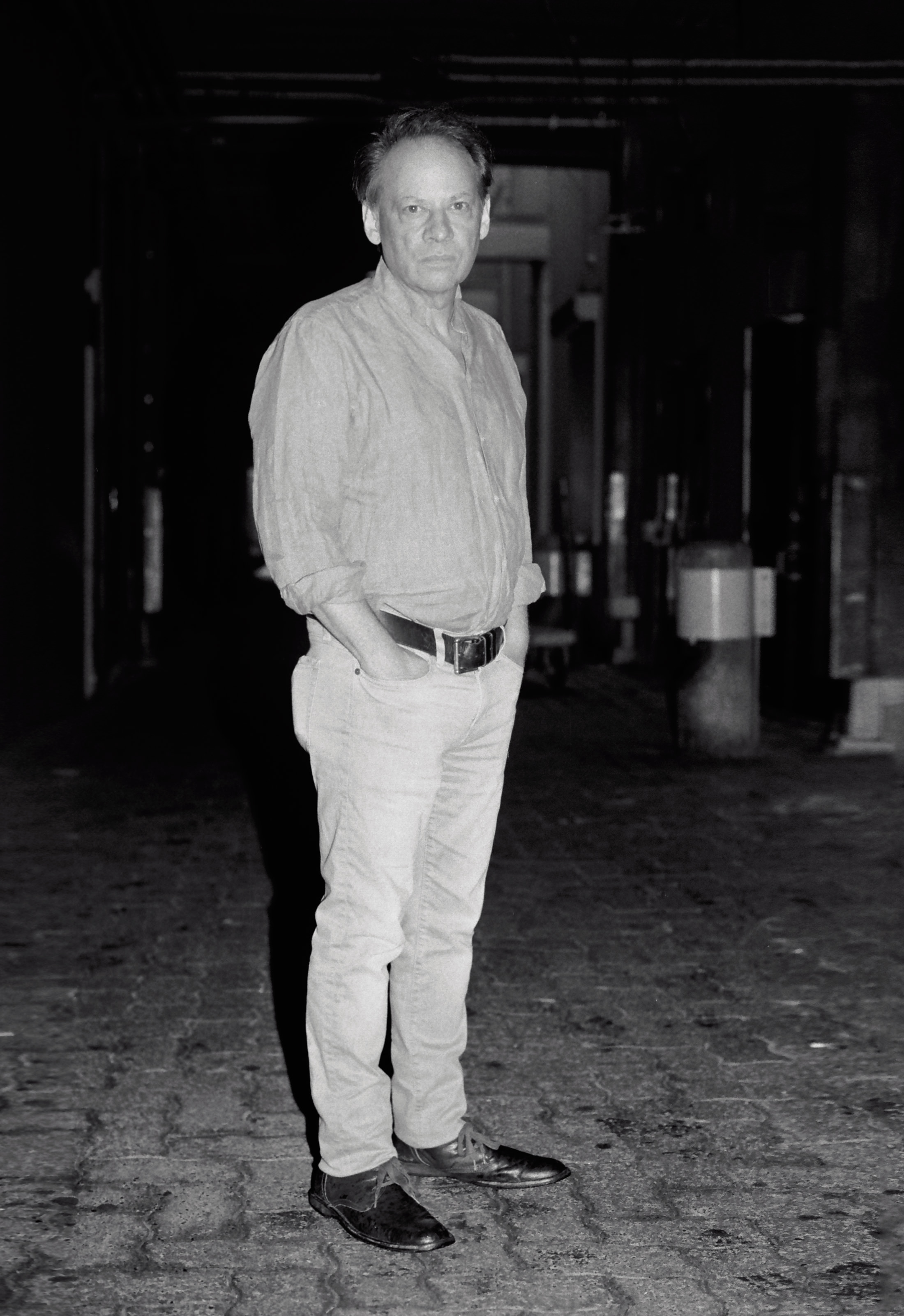

The New Yorker essayist Adam Gopnik meditates on Manhattan, marriage, and a life of letters.

-

Born in Philadelphia and raised in Montreal by professor parents, Gopnik graduated from high school at the age of 14.

-

Adam Gopnik speaks as he writes. His conversation is animated, lyrical; he is prone to circuitous ruminations, forever wandering off topic.

Adam Gopnik

Empire state of mind.

Adam Gopnik often has dreams about the apartment he and his wife, filmmaker Martha Parker, shared when they first arrived in New York, almost 40 years ago. It was a 9×11 basement studio on the Upper East Side, on 87th Street near First Avenue, and cost $379 a month. They referred to it as the Blue Room, after the 1926 Rodgers & Hart show tune (“We’ll have a blue room/a new room/for two room…”). Cramped, cockroach infested, and with bad air circulation, it was nevertheless magical for the 23-year-old Gopnik, serving as ground zero for three of his lifelong loves: marriage, Manhattan, and the literary life.

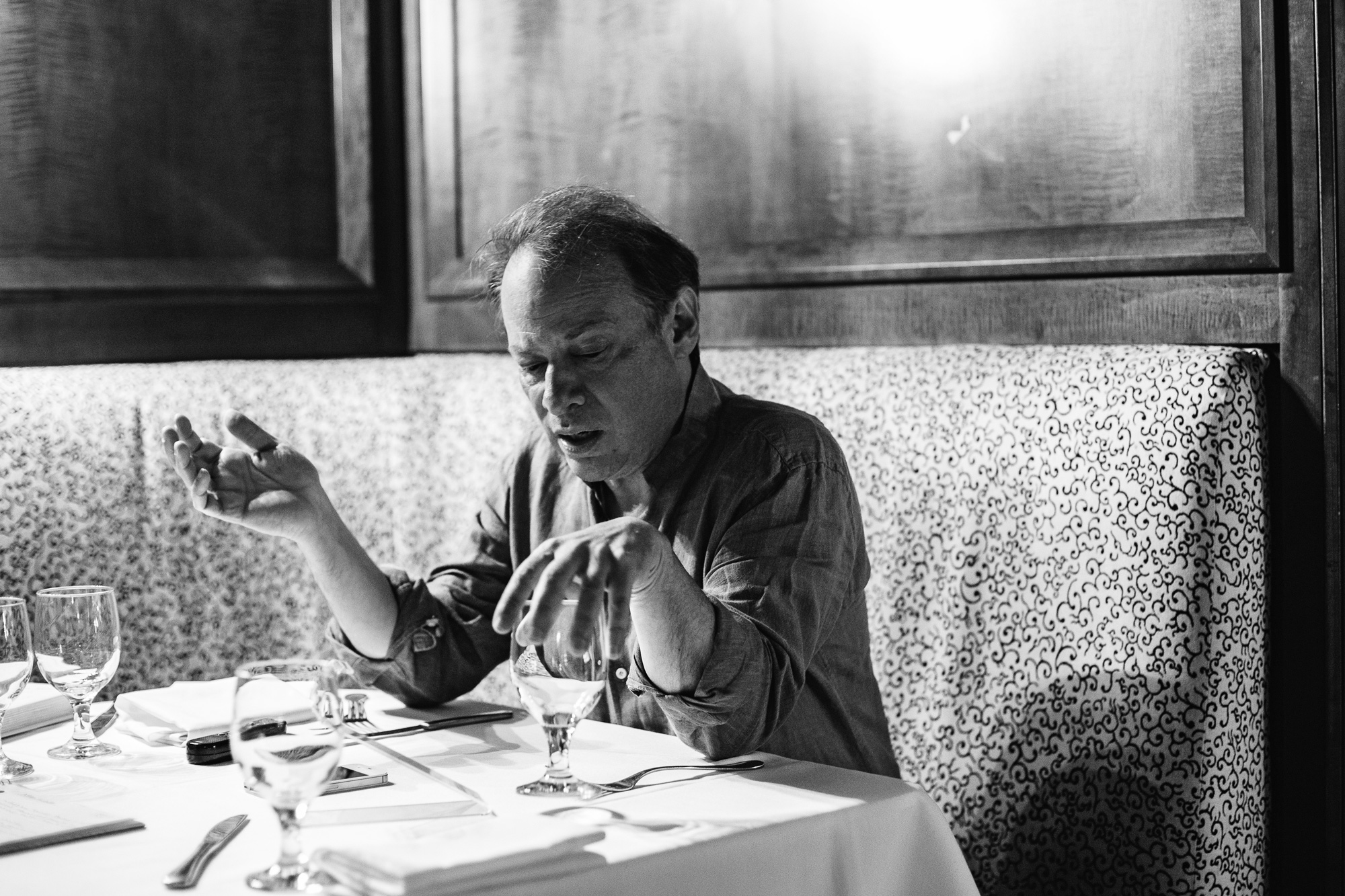

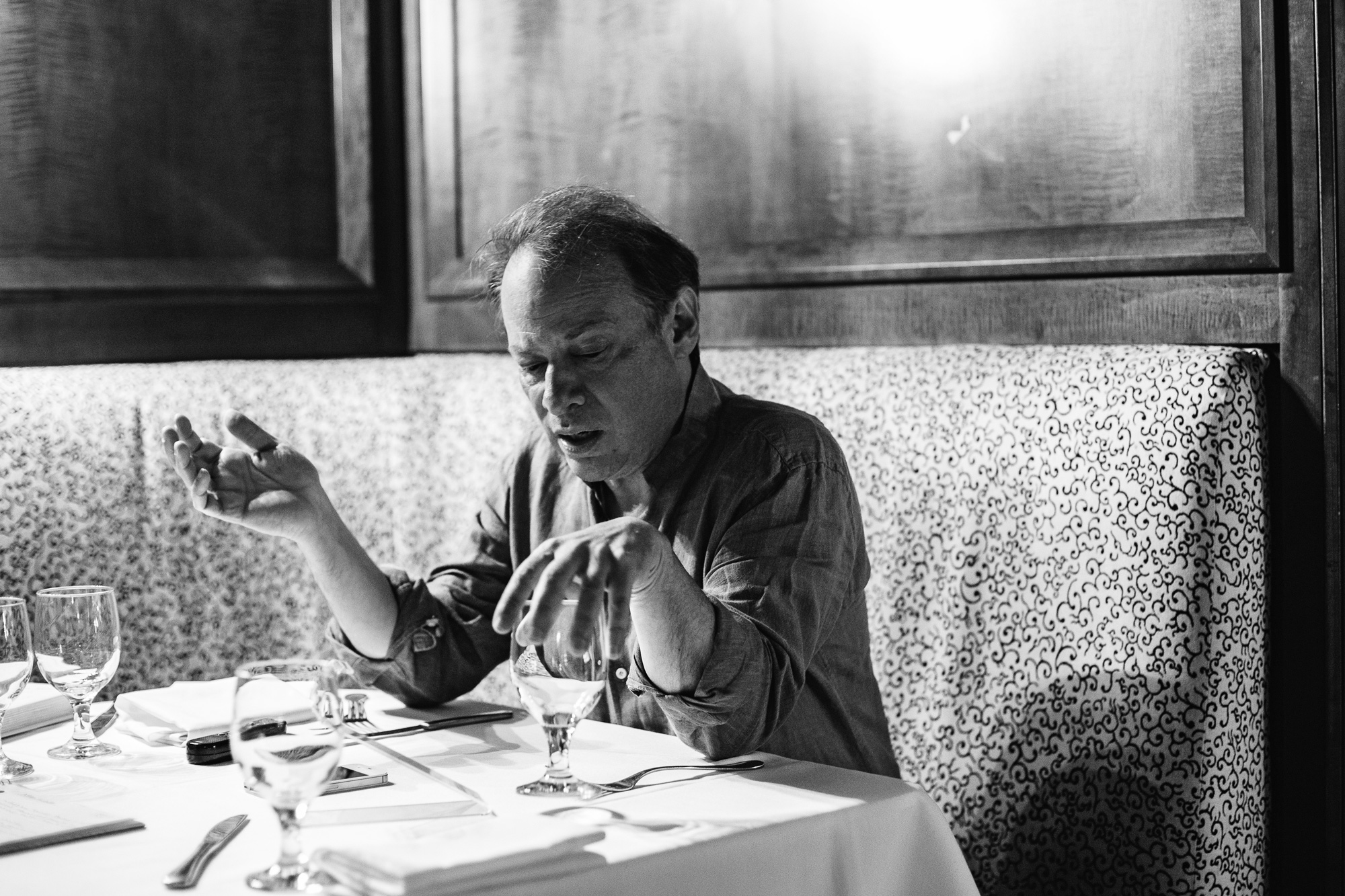

At a sold-out event at the Vancouver Writers Fest this past October, the The New Yorker scribe speaks of the three years he and his wife lived there with playful irreverence, amusing his audience with tales of the couple’s absurd attempts to sleep, eat, read, write, work, and love in such a tiny space. But earlier that day, over a bowl of seafood chowder in the nearly empty lounge of Granville Island’s Dockside restaurant, he’s decidedly more wistful—not just for moments passed in his own life, but for a moment passed, period.

Born in Philadelphia and raised in Montreal by professor parents, Gopnik graduated from high school at the age of 14.

The cosmopolitan literary world that Gopnik came of age in is crumbling. It’s a point he illustrates in his recent memoir, At the Strangers’ Gate: Arrivals in New York (published by Knopf Canada), noting his shock at seeing Lena Dunham’s character in Girls feeling stuck in the exact same place at the men’s magazine where Gopnik worked as a fashion copy editor—the job that launched his career. “We all felt that if you got your foot on the ladder of ambition, on a lower rung, the likelihood was with some gumption and perseverance, you would climb up,” he says. “And I’ve noticed very strongly in the twentysomethings I know—including my own—that they don’t feel that way.” These days, rents are impossibly high, salaries impossibly low, and opportunities frustratingly scarce. Ambition has been replaced, as his young officemate Alexandra Schwartz likes to remind him, by a desire for adequacy. Ascension is now the exception, not the rule. Gopnik’s memoir is as much about this story as about his own.

Adam Gopnik speaks as he writes. His conversation is animated, lyrical; he is prone to circuitous ruminations, forever wandering off topic.

Born in Philadelphia and raised in Montreal by professor parents, Gopnik graduated from high school at the age of 14. Five years later, he met the Icelandic-Canadian Parker, the prettiest girl he’d ever seen. After completing a bachelor’s degree in art history at McGill, he was accepted into grad school at NYU. In August of 1980, he and Parker boarded a bus south, booking into a Midtown discount hotel. Not long after, they wed at city hall and began building a life in the Blue Room.

He was a restless insomniac, she an inveterate sleeper. Gopnik cooked her elaborate French fare (they squabbled over whether meat should be rare or well done), studied, walked the streets, gave lunch lectures at the Museum of Modern Art, and, in 1983, landed the job at GQ. That same year, the couple moved to a loft in SoHo that was overrun by rats, placing them at the centre of the art world. It was here that Gopnik was mentored by photographer Richard Avedon; Gopnik eventually became The New Yorker’s art critic.

Recalling this upward trajectory, the author speaks as he writes. His conversation is animated, lyrical; he is prone to aphorisms and circuitous ruminations, forever wandering off topic to share a telling anecdote. Thus, we move from pop culture icons like Bruce Springsteen to the current epidemic of anxiety, Twitter, his two children, the novelist Meg Wolitzer (his wife’s best friend), Lorimer Shenher’s book on the police handling of serial killer Robert Pickton (That Lonely Section of Hell), and an old GQ cover story on Donald Trump. Eventually, we arrive at the subject of the old guard of The New Yorker, known to get drunk and start furious rows, slamming fists on tables, shouting at editors, and going AWOL for 18 months at a time. (What did they do during those 18 months, Gopnik wonders. How did they pay the rent?)

In his early years at the magazine (he started there in 1986), Gopnik got to know literary luminaries like Joseph Mitchell, who famously came into the office every day for the last 32 years of his life without publishing a single piece. Gopnik recalls one particular lunch with him in which he, hungry for the secrets of success, probed Mitchell about the great writers of his generation, including A.J. Liebling, E.B. White, and James Thurber. Mitchell was always one who preferred to listen rather than talk—a lesson in itself—but he finally answered. Each one, he suggested, had a “wild exactitude” of their own.

Gopnik has become a literary luminary, the author of eight books including the bestselling Paris to the Moon.

“It captured exactly what it was that I love in their writing, but I was ambitious for in my own writing,” Gopnik says. “And that’s the ability to be kind of wildly, almost extravagantly meticulous…Every imaginable detail that you could get right, could get exact, you should do. But that it was inadequate if you didn’t have some other note of madness to it, if there wasn’t some countervailing force that made it a little crazy.”

Gopnik went straight back to the office, wrote the phrase on a 3×5 card, and pinned it over his typewriter. Fifteen laptops later, it is still there.

Adam Gopnik speaks as he writes. His conversation is animated, lyrical; he is prone to circuitous ruminations, forever wandering off topic.

In the intervening decades, he has, of course, become a literary luminary himself, the author of eight books including the bestselling Paris to the Moon, about the years he and his family spent in the French capital. He’s written musical theatre lyrics, opined on the CBC and the BBC, and cultivated a speaking career that saw him deliver the 2011 Massey Lectures (following in the footsteps of Jane Jacobs, Doris Lessing, and Martin Luther King Jr.). All the while, he continued to write for The New Yorker, on topics ranging from meditation and Hugh Hefner to gun control and mass incarceration.

He has, throughout, remained deeply in love with his wife. Dedicated to her, At the Strangers’ Gate is the story of a happy marriage, but it is also the story of an erotic one—a topic rarely broached in books. Gopnik jokes that few people want to read about married people’s sex lives; the week of our meeting, a reviewer with Britain’s Spectator confirmed this in print. But we should not dismiss this clear-eyed window into the satisfactions of long-term love, which Gopnik describes as a balancing act between lust, laughter, and loyalty. His relationship with New York has been no less steadfast. The glamour of the city has drained off, sure, as has the specificity. In the urgency of day-to-day family life, Gopnik says, he often goes whole days without noticing he is living in New York. But there are still moments, leaving the all-night drugstore across the street from his home, say, when he looks up at his apartment’s windows—six of them now, instead of the Blue Room’s one—and feels an undiminished sense of wonder. He thinks to himself, Wow, Martha and I live there? “In that way,” he says, “my sense of disbelief at having been able to do it is never-ending.”

Never miss a story, sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter, here.