Goethe said architecture is frozen music. A Joni Mitchell song is a liquid painting. If you want an ideal, long-range view of Joni Mitchell, from her pure-voiced beginning to her sultry, seasoned present, listen first to “A Case of You” on the 1971 album Blue and then the burnished version recorded three decades later on Both Sides Now. The eroticism remains and both versions have the same eyes, but one has the sad-sweet heart of a girl, while the other has the heart of a worldly woman who no longer celebrates sorrow, only witnesses it.

This later recording presents a kind of ripe, feminine sensuality sometimes undervalued in mainstream, youth-fixated North America, but held precious in other cultures, and among all those who care about Lady Day and the Little Sparrow. Tom Scott, reeds player, composer, arranger, and consummate session player broke new ground with Joni (on Court and Spark, 1972). “What an experience that was! She brings out the best in you, but you have to give her everything you’ve got.” That is true for those who have played with her, and remains true for her listeners. Mitchell structured the songs in Both Sides Now (2000) as the progression of a love affair, making these classics as affecting as the memory of a first kiss. The story rolls out like a tapestry, from the wild first moment (“You’re My Thrill”) to the philosophical aftermath (“I really don’t know love at all”). Many who grew up with Joni Mitchell’s music will relive an intensely remembered moment, as they listen to her reinvestment in this signature song.

Roberta Joan Anderson, an only (lonely?) child, was born November 7, 1943 in Fort MacLeod, Alberta. When she was six, her family moved one province east and settled in Saskatoon. She was born rare, and she’s paid for it. It’s not as if a baby asks for talent. But when it hits like lightning, where’s the choice? You’re set apart, and if you get out of that first phase of realization intact, you spend the rest of your life trying to take responsibility for the gift. Or not.

“When I was two feet off the ground,” she writes, “I collected broken glass and cats. When I was three feet off the ground I made drawings of animals and forest fires. When I was four feet off the ground I discovered boys and bicycles.” Then at age nine, disaster. Polio. Those were pre-Salk summers, and she learned a grown-up truth too soon: life can turn and strike you down. But she recovered, and soon after smoked her first cigarette. Loved it; “I took one puff and felt really smart”. We can see the archway leading to her dancin’ years. Hurry up and have fun.

Joni Mitchell with Graham Nash. Photo courtesy of Henry Diltz.

Mitchell meant to walk a straight line into a career as a painter, but along the way she bought a $36 baritone ukulele and the music began. She travelled to the Mariposa Folk Festival, and then, soon to be a struggling single mother, became part of Toronto’s Yorkville coffee house scene. Along came folk singer Chuck Mitchell, ready to take both her and her infant daughter. With mixed feelings, she married him. But something happened, and a few weeks later, Joni gave up her daughter for adoption. She had named the baby Kelly, and the song “Little Green” contains feelings from that period: “Call her green and the winters cannot fade her. Call her green for the children who made her.”

Joni and Chuck Mitchell moved to the United States. But before her own songs could emerge, they needed a container. This was to be the open tunings taught her by folk singer Eric Anderson, an open G, a drop D. “Once I got some interesting chords to play with, my writing began to come,” she said. Eric Anderson’s tunings may have unlocked the door, but Mitchell threw it wide open to the flatlands of her childhood. Her constant, haunting modal harmonies, the result of the unusual tunings and the sounds in her head, take us to those howling prairies.

After her divorce from Chuck in 1967, Joni shifted gears, moving to New York City’s Chelsea district. Tom Rush recorded “The Urge for Going.” So did country singer George Hamilton IV, who made it a hit. Buffy Saint-Marie (“The Circle Game”) and other artists with good noses began recording Mitchell’s songs, but the breakthrough was Judy Collins’s recording of “Both Sides Now.” Collins, in her 1987 autobiography Trust Your Heart: “Joni Mitchell came down from Canada to add the poetic lustre of her songs to our musical lives. Joni’s songs are delicate and feminine and strong, like she is.” Collins told Mitchell, “You can break my heart anytime you like. Just open your mouth and sing.”

___

Mitchell meant to walk a straight line into a career as a painter, but along the way she bought a $36 baritone ukulele and the music began.

Performing in Florida, Mitchell met David Crosby, who was taken with her and helped convince Reprise Records, the company founded by Frank Sinatra, to let her record a solo acoustic album without the folk-rock overdubs then in vogue. Crosby got the producer’s credit, but it was clearly Mitchell’s vision. She also painted her first album cover.

Mitchell moved to California and moved in with Crosby, then beginning his association with Stephen Stills and Graham Nash. In 1968, Collins’s recording of “Both Sides Now” soared up the charts, fuelling momentum for Mitchell’s second album, Clouds, released in April 1969 and a Grammy winner in 1970. After yet another circle game, Mitchell bought a house in Los Angeles’ Laurel Canyon with Nash. This union inspired her Ladies of the Canyon album (1970) and Nash’s famous “Our House,” forever remembered as “a very very very fine house, with two cats in the yard.” It is on the immortal Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young album Déjà Vu. So is an electric cover of Joni’s “Woodstock.”

Joni Mitchell with arranger-conductor Vince Mendoza. Their collaboration won a Juno and a Grammy. Photo by David Mingus and Leslie Mixon.

Like most singers, Joni has two voice breaks. Unlike most singers, who work to minimize those breaks, she made art of hers, developing an otherworldly kind of yodel (as on the almost Hebraic ending of “Woodstock” and the acappella ending of “Rainy Night House.”) Her voice danced across the two-plus octaves at the end of “Big Yellow Taxi”— “they paved paradise and put in a parking lot.” She has never made a big deal of her range, but it is mighty.

Mitchell falls instinctively into onomatopoeia, singing not just notes, but meanings; for example, the stretch on “go” in “deep kisses and the sun going down” on “Lesson in Survival” (For the Roses, 1972). And it’s not just the voice; it’s the phrasing. Mitchell strings together lyrics of near-Faulknerian length with impossible grace and dizzying syncopation, never bruising a tempo. Her songs have been covered hundreds of times, but no one tries to repeat her phrasing. (Bonnie Raitt came closest on “That Song About the Midway,” because her voice has similar colour and agility.). Try to imitate her line “I was a free man in Paris, I felt unfettered and alive” while you’re stuck in traffic sometime.

Tom Scott recalls, “My first exposure to her music was when Quincy Jones suggested I listen to her version of “Woodstock” and record it, which I did. Joni’s engineer, Henry Lewy, played my version for her. Meantime, she was thinking about working with a band, something she had never done before. Henry introduced us and I worked on the Beethoven thing [“Judgment of the Moon and Stars (Ludwig’s Tune)”, on For the Roses]. It was an amazing experience; I’ve never had a better creative collaboration. Joni used to call it a Ping-Pong match, the way we bounced ideas back and forth.” (Scott’s stacked flute parts on “Barangrill” on that album amazingly mirror Mitchell’s vibrato on the line “eggs over easy.”)

“Then,” Scott continues, “she came to see me with my band at a club and asked if we’d all work on her new album (Court and Spark). Are you kidding? We went on a tour that lasted forever (producing the double album Miles of Aisles in 1974). We did over seventy-five shows, and I was never tired of it, never floating through. She said our show was one-third songs and two-thirds tuning, because of all her instruments. She was exacting about tuning. I remember standing backstage and listening to her unbelievable intensity. It was like eavesdropping on her soul.”

2000’s “All-Star Tribute to Joni Mitchell” included performances by James Taylor, Cassandra Wilson, Shawn Colvin and Elton John. Photo ©AFP/CORBIS/MAGMA.

So effortless is Mitchell’s manner that few people recognize the profound level of her skills. Among them from the start was impeccable time. A lesser player pushes and pulls the time. Equally strong is her piano playing. In 1972, recording was analog. What you played was what you got. Mitchell builds dynamic and varied rhythmic patterns, as well. Add to that the plaintive open harmonies and the deep rich sounds she cultivates on string instruments, and the effect is hypnotizing.

___

Both versions have the same eyes. but one has the sad-sweet heart of a girl, while the other has the heart of a worldly woman who no longer celebrates sorrow, only witnesses it.

Her songs can be recitatives with chords, but her sheer musicality turns most of them into melodic treasures. In “Barangrill,” a traveller stops at a diner and envies the waitresses: “No trouble in their faces, not one anxious voice, none of the crazy you get from too much choice, the thumb and the satchel or the rented Rolls Royce”; lyrics full of weariness with touring. Frustration with the demands of the industry become more explicit in “Free Man in Paris” in which the singer feels penned in by “the work I’ve taken on, stoking the star maker machinery behind the popular song.”

A cast of characters comes to life in The Hissing of Summer Lawns. “The Boho Dance” is about not quite belonging: “But even on the scuffle, the cleaner’s crease was in my jeans, and any eye for detail caught a little lace along the seams.” And “Nothing is capsulized in me on either side of town, the streets were never really mine, not mine these glamour gowns.” Enter the pimp in “Edith and the Kingpin.” A girl named Edith “maybe from a small town, right? Women he has taken grow old too soon; he tilts their tired faces gently to the spoon.” But it’s Edith who haunts us, not the Kingpin. In Turbulent Indigo (1994) we hear Mitchell’s descent into energy-draining darkness, weirdly Biblical in “The Sire of Sorrow (Job’s Sad Song)” and “Sunny Sunday,” which isn’t. “Blame takes aim” is an economical and harrowing rhyme in “Last Chance Lost,” and her individuality shines on a rare non-original, “How Do You Stop,” once a pop hit by the late Dan Hartman. Don’t forget her priceless kick-ass songs: “Raised on Robbery,” “You Turn Me On, I’m a Radio,” “Big Yellow Taxi,” “This Flight Tonight.” She could always rock when she wanted to, and still say something profound.

And then there is the Mingus period. Mitchell had long been drawn to the risk-taking world of jazz (her heroes were Miles Davis and Picasso). As early as 1962, she had sung “Twisted,” quirky lyrics set to a Wardell Gray solo, with LA Express. Later she would work with Wayne Shorter, Gerry Mulligan, Herbie Hancock, Tony Williams, Don Alias, Jaco Pastorius, Joe Sample, and, most significantly, Charles Mingus himself. Her tribute to the towering bassist/composer/bandleader can be heard on Mingus (1979). And her painting “Mingus Down in Mexico” is one of her most affecting.

Mitchell and Mendel Gallery curator Gilles Hébert with Joni Mitchell; “Incredibly witty, really bright, a pleasure to be around.” Photo by Grant Kernan.

Mitchell has had astonishing consistency as a songwriter, but the going was challenging for some longtime fans, with her experimental productions from ‘88 through the mid-’90s. The sound changed dramatically, becoming edgier, more electronic. She had always been a hands-on producer, but before this, we didn’t have to notice. Production values were, to some ears, overdone.

But this era produced some of her finest work, from striking duets with Peter Gabriel (“My Secret Place”) and Willie Nelson (“Cool Water,” a prairie song if ever there was one) both from Chalk Mark in a Rain Storm, 1988, to wistfully energetic and soulful tunes (“Night Ride Home” and “Come in from the Cold” from Night Ride Home, 1991) and “The Beat of Black Wings” with its echo of “Johnny Angel” in the refrain. This period also begat “Passion Play (When All the Slaves are Free),” (“Who’re you gonna get to do the dirty work?”) and one of her best songs ever: the haunting, unforgettable “Magdalene Laundries,” from Turbulent Indigo.

Rob Bowman, a music professor at York University, Toronto, first educator to lead a course in pop music in Canada and a regular on CBC Radio One’s Definitely Not the Opera, remembers these albums “exploring places and spaces you don’t think of a woman singer going.” Bowman was at a Mitchell concert in Detroit, in which she performed with an orchestra, singing songs from the new album. “For a lot of fans, it was quite a challenge. This was pop music of its day, but no longer easy listening for people of Joni’s era. But,” says Bowman, Mitchell “has always treated herself as an artist, has always honoured the muse, remaining faithful to the art, bringing to her work integrity with intensity, realizing from the beginning that while money is never insignificant, art is paramount. And there is always that higher bar to scale: Bob Dylan, Neil Young and Joni have consistently reinvented themselves.

For the Both Sides Now project, Mitchell and Larry Klein, co-producer, music director and ex-husband, set things right, flying to London to record with a seventy-piece orchestra augmented by outstanding soloists and a driving rhythm section. Arranger Vince Mendoza’s arrangements make the orchestra seem even larger, thanks to exquisite balancing, aided by engineers Geoff Foster (UK) and Allen Sides (US).

___

“When I was a kid, the first thing I remember performing on stage was ‘Raised on Robbery’, says Brooks.

Mendoza’s introductions and codas are jewels of their own. The intro to “You’re My Thrill” bows for a moment to legendary orchestrator Gordon Jenkins and then becomes Mendoza’s own. In “At Last,” the hokey, commonly used 6/8 piano pattern, cushioned deep in the orchestral sound, becomes dreamlike. Some arrangements (especially “A Case of You”) have a solemn dignity. Others have the heavy drama of soundtracks for 1940s Warner Brothers movies. Some swing a little, or as much as an orchestra can with twenty-eight violins, eight violas, seven celli and a harp. Many are ignited by the brilliant solos of Wayne Shorter (soprano and tenor saxophones), Herbie Hancock (piano) and award-winning film scorer Mark Isham (trumpet), powered by Chuck Berghofer, bass, and Peter Erskine, drums.

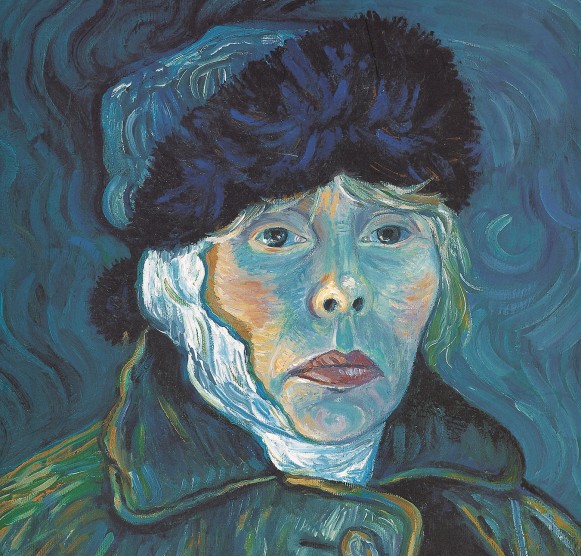

Joni Mitchell’s Van Goghesque self-portrait.

Mendoza says, “You can really hear economy in motion in [Mitchell’s] voice, and, with a seventy-piece orchestra, I put a lot of construction around her. A lot of it was about where we didn’t want to go with the songs. I tried to stay out of the way, so they wouldn’t turn into Broadway show tunes. Really, we thought of them as art songs.”

Only two of the songs on the album are Mitchell’s. The others are standards, mainly torch songs, from “You’ve Changed” to “Don’t Worry About Me.” “The biggest challenges,” said Mendoza, “were [Joni’s] songs, because I was so familiar with them. We pared “A Case of You” down to its essence and did it much slower than the original. I gave “Both Sides Now” quite a nebulous setting, a dangerous approach, because it could have floated away. But it seemed to work.”

Although you can hear echoes of Billie Holiday, Peggy Lee, Morgana King, Anita O’Day, Chaka Khan, Sarah Vaughan, and others in Mit-chell’s voicings, the album is not a cheap tribute (translation: imitation) but rather a deeply skilled appreciation of admired singers and musicians and arrangers. Authenticity is character. Mitchell and Mendoza rarely used the key change after the bridge approach to dynamics. They didn’t need it. Mendoza’s dynamics rely on exquisite orchestral balancing; Mitchell’s rely on her bone marrow. Mitchell casts musicians adroitly, many from the jazz world, but the Crosby-Stills-Nash boys are never far away. Joni didn’t always sound as much at home in jazz as she felt, but that has changed. The years, the blues, the cigarettes took her there. This album is city work, not prairie. And in her personal life, the circle went ‘round and ‘round, and Joni found her 1965 child, Kelly, now Kilauren. Both Sides Now is dedicated to her.

Love and respect for Mitchell were palpable on a television special called “A Case of Joni” (album on Reprise). Among the artists paying homage: Elton John, k d lang, Janet Jackson, Bjork, Etta James, Stevie Wonder and Sarah McLachlan. When the camera panned to Joni, she looked overwhelmed.

She is an essentially private person, not uncommon in many who live their performance lives in the public’s eye. She discourages, disdains, focus on her private life rather than her art. But she has allowed at least one excellent, comprehensive biography: Both Sides Now, by Brian Hinton, published in 1996 by Sanctuary Publishing Limited, London. And Mendel Art Gallery director Gilles Hébert, curator of voices: Joni Mitchell, says, “She is not aloof, she’s over-extended.”

Mitchell’s powerful influence continues to grow. Meredith Brooks, singer, songwriter, guitarist, exploded onto the pop-rock scene in 1998. In 1999, she was part of the Lilith tour, a surprise success showcasing the current cream of young women artists. Each night they ended the show jamming on Joni’s “Big Yellow Taxi.” “When I was a kid, the first thing I remember performing on stage was ‘Raised on Robbery’, says Brooks. “I think it’s the first song I ever learned. I got my first vocal experience listening to Joni. She crossed the line into a different kind of soul singing from other influences on me, like Chaka Khan. She’s a poet, but the cool thing is she was always conversational, so when I listened, I didn’t feel so psychologically lost. With alternative music, where writers say stuff like ‘I just write what I feel and let people work it out’ I would feel exhausted. [Joni’s] vocals were always deep, but sounded effortless.” Brooks adds, “People don’t realize what a great guitar player she is, and those tunings! On my last album, when I was layering for a really full, shimmery sound, I would first play a track in what I call the missionary position. Then we would re-tune our guitars with what they call in the studios ‘the Joni Mitchell tunings.’ Then we’d go through and add layers. So here I am, still learning from Joni.”

The last thing Joni Mitchell might have expected was her emergence as a voice of conscience during a particularly brittle cycle in pop music. But she is not afraid to speak out about today’s business approach to music, with the corporation as mentor and the artist as corporate enthusiast. Her long, unyieldingly artistic career backs her anger and integrity. You can’t get around her. “I’m a runaway from the record biz, from the hoods in the ‘hood and the whiny white kids, boring! The old man is snoring and I’m taming the tiger…nice kitty-kitty…the moon shed light as the radio blared so bland; every disc jockey a poker chip, every song just a one-night stand.” (Taming the Tiger, 1998.)

Few have ever evoked the pain and longing of love as well as she; many of us were with her every song along the way. Revisiting her powerful catalogue (all still selling) is like revisiting one’s own wild history.

“Everything comes and goes, marked by lovers and styles of clothes” (“Down to You,” Court and Spark). If we lived in a time or a part of the world that did not pay its poets and minstrels, I think we all know that Joni Mitchell would have done exactly as she did, and “played real good for free” (Ladies of the Canyon). Never stuck where she is, she continues to explore new creative territory. She does not imitate herself. She is herself. Every time.

Perhaps it was appropriate that voices: Joni Mitchell, the first retrospective of thirty-five years of the artist’s work, should open at the Mendel Art Gallery in Saskatoon. It was at the home of Frederick S. Mendel, who founded the gallery in 1964, that Mitchell first saw paintings of such artists as Picasso and Matisse.

Mendel, born in Germany, lived in various European cities and in New York, then moved to Saskatchewan’s first university city in 1940 and began what became a successful meat processing business. He amassed a large collection of paintings, including works by Canada’s Group of Seven and Emily Carr, and by American and European giants.

“I felt most touched by van Gogh,” Mitchell revealed to New York Times interviewer James Brooke, “Van Gogh was impulsive. For him, art was like sex on the kitchen table.”

There was another (unrelated) artistic Mitchell at the formal opening: actress Camille, Mendel’s granddaughter (daughter of Joanna Mendel and Cameron Mitchell, the actor best remembered as “Happy” in the original stage and film productions of Death of a Salesman). It was Camille’s oldest brother, Robert, who had taken Joni to his grandfather’s house to see the collection of paintings.

Camille Mitchell served as mistress of ceremonies at the opening, and, with her family, provided support for the exhibition. (Investors Group was the primary sponsor; the Potash Corporation of Saskatchewan and SaskTel were other supporters.)

___

“I felt most touched by Van Gogh. He was impulsive. For him, art was like sex on the kitchen table.”

The Mendel presented more than 85 works, matching them with illuminated enlargements of the artist’s lyrics and poems, and the gallery was flooded with the sound of Mitchell’s voice, in song.

All worked together, as Mitchell calls her songs “audio paintings.” In one of the most famous, “A Case of You,” she wrote “I am a lonely painter, I live in a box of paints.” Gilles Hébert, director of the Mendel and curator of voices: Joni Mitchell, told Brooke “She will talk about colour chiming or tension built up because of discord….She talks about harmony, she talks about resonance. These are the terms she uses to describe her art.”

Some of Mitchell’s paintings have a direct reference to music and musicians: Mingus Down in Mexico, Round About Midnight, Black Orpheus. Others—Homage to Matisse, Georgia O’Keefe’s Rainbarrel—salute painters. And then there are pictures that carry the titles of Mitchell’s songs and albums: Both Sides 1 and 2, Taming the Tiger.

Curator Hébert said Mitchell’s songs had a “considerable influence on me in my late teens and when in university.” And, her music’s impact proved so pervasive, “it has always been with me.”

But Hébert truly became a fan after meeting her, finding her “incredibly witty, really bright, a pleasure to be around.” He won’t soon forget being with her as she edited Both Sides Now while “bombing down Sunset Boulevard.”

There have been invitations from galleries in Canada, the US, and Europe, but Mitchell’s primary interest was having the show in Saskatoon in a gallery only a mile from her parents’ home.