-

-

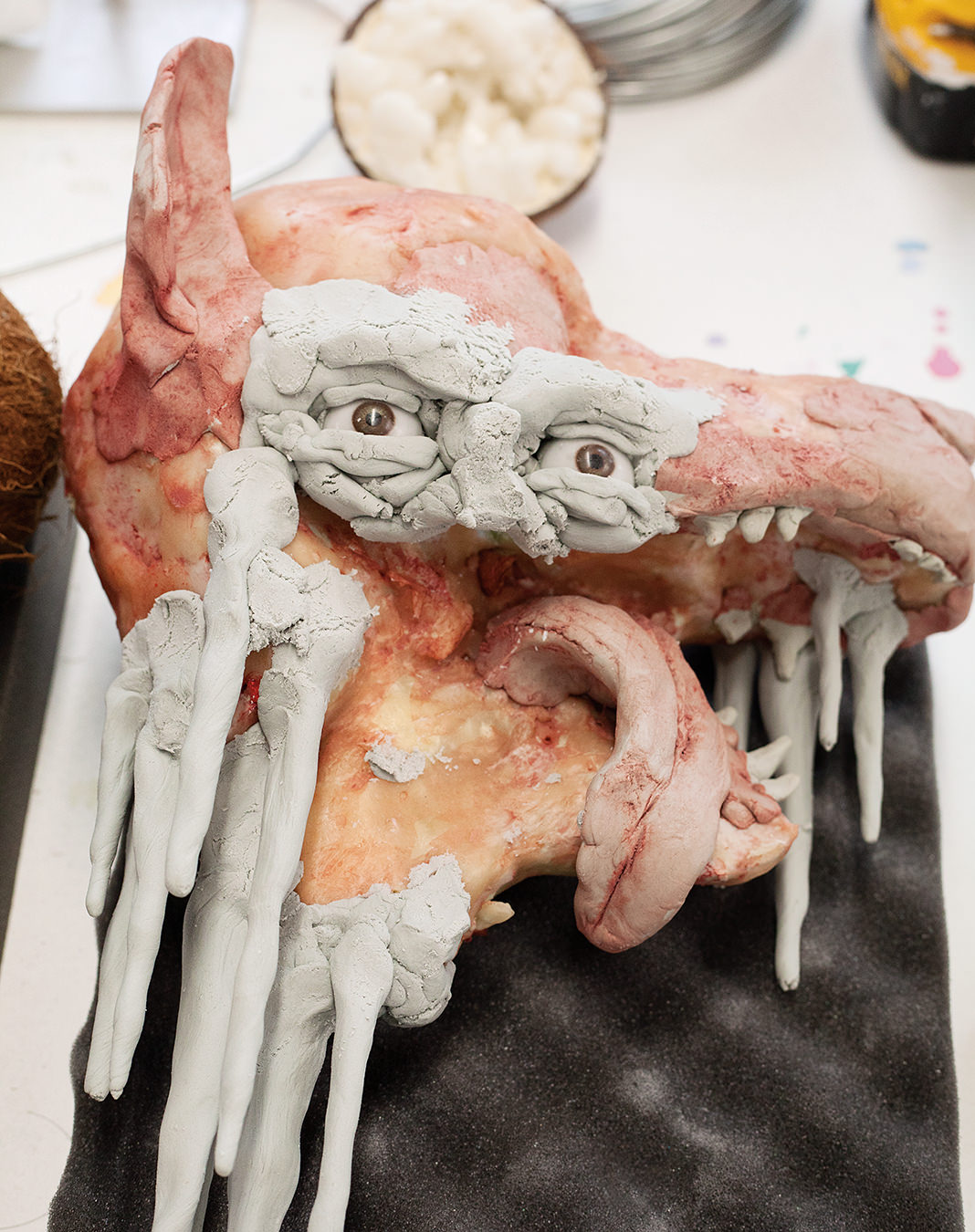

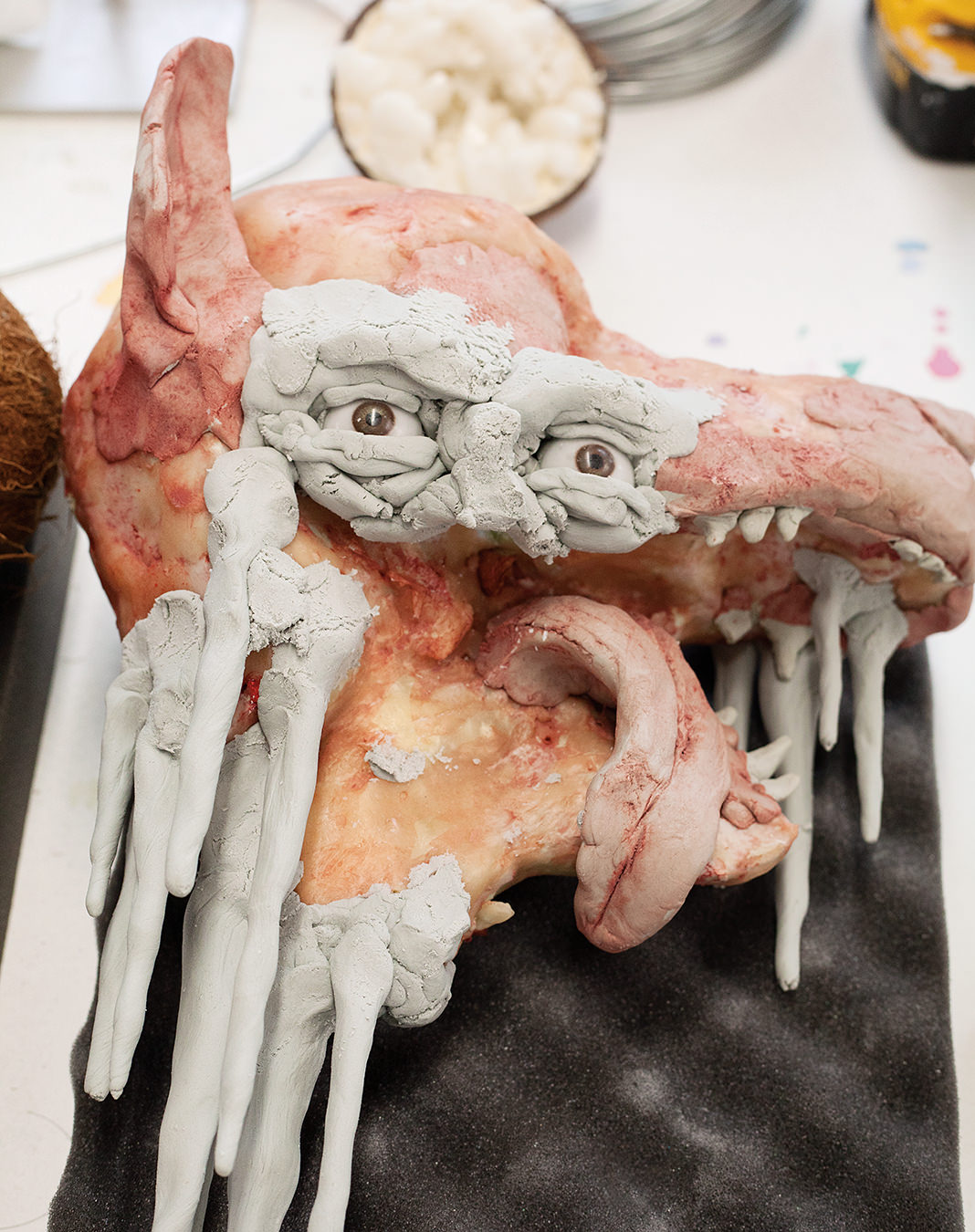

Artworks in progress at Altmejd’s studio in Long Island City, New York.

-

-

-

Altmejd’s large, bright studio space is a hub of activity.

-

-

-

David Altmejd

Artist's wonderland.

Walking into David Altmejd’s studio feels like falling down a rabbit hole into some strange wonderland. Hidden on the top floor of a Long Island City warehouse that’s just one subway stop from Manhattan, the large, bright space is a hub of activity in preparation for the friendly, bright-eyed artist’s big (untitled) solo show at the Brant Foundation Art Study Center in Connecticut.

Four cheerful assistants scurry about, putting finishing touches on sculptures in various states of inhuman condition. One glues hair upon the thigh of a 12-foot giant. Another voraciously hammers a wooden skeleton that will become a plaster mannequin. Yet another collects countless tiny resin grapes, and dozens of disembodied heads—an Altmejd specialty—look on, duly impressed.

“Be careful, Lucas! Careful with your fingers,” the 37-year-old artist calls to an assistant who looks like he might cut himself while slicing a block of foam into the shape of an enormous hand.

Altmejd’s acclaimed work often delves into themes like transformation and containment, and his inclusion of mythical creatures, including giants, werewolves, and angels, invites science fiction and mythology references. Ultimately, it resists definition or narrative, and is all about potential. His sculptures and installations have shown at prestigious museums such as Grenoble’s Le Magasin Centre National d’Art Contemporain and Barcelona’s Fundación la Caixa Museum, as well as throughout the United States (where he is represented by New York’s Andrea Rosen Gallery), in London, and in Canada.

In 2007, the Montreal expat represented Canada at the Venice Biennale. The Giant 2 was a decaying aria of mirrors, taxidermy, and plants centred on a werewolf. A second piece, The Index, featured a cacophony of life-sized human figures with bird heads, more foliage and mirrors, and werewolf heads. The following year, his installation The Eye turned heads at New York’s Metropolitan Opera House. In 2009, Altmejd won the Sobey Art Award, and recently, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts unveiled The Eye (another work with the same name), an outdoor bronze sculpture commissioned for the museum’s new wing.

Altmejd’s acclaimed work often delves into themes like transformation and containment, and his inclusion of mythical creatures, including giants, werewolves, and angels, invites science fiction and mythology references.

“It was extremely meaningful for me,” he says of the hometown coup. “Also, it was unlike everything I’ve ever done. Just the fact that it’s a public sculpture, it’s a totally different logic. I had to think of things like timelessness, not just in terms of material but in terms of form.”

Yet having no constraints also gave him a sort of vertigo. “I felt I was in space. It’s hard to describe—I just feel like usually I’m not really responsible for the work, because the work is the result of every constraint that surrounds it. But for that piece, I feel really responsible. That piece is very connected to my work but it’s also very different in how I conceptualized it: I thought the idea of the symbol was extremely important. Symbolic potentiality—shapes and forms and holes that were potentially symbolic.”

Perpetually concentrating on the present moment, Altmejd has never really been able to step back and look at his career. “I’m just focused on the now. I don’t have choice; that’s all I see,” says the artist, who studied biology at McGill University before switching to art school at L’Université du Québec à Montréal, and then moving to New York to earn his MFA at Columbia; he’s lived there since. “I’m fascinated with the living, with biology—especially evolutionary biology. I don’t see big pictures—I never really step back—but I think my focus on details makes it possible for things to be made.”

The past, not the present, used to occupy Altmejd’s attention. “When I was a kid, I was totally obsessed with the past, with the idea of time passing. I started experiencing nostalgia when I was, like, seven or something,” he says with a laugh. “That made me really, really, really sad. When I was eight and looked at pictures of when I was five, I was tearing up. Then when I was a teenager, everything changed and I became obsessed with the present.”

Featuring new and old work, the massive scope of his new Brant Foundation show reveals Altmejd’s hyperfocus to be a prolific one. “I decided to make as much work as possible so I could have something to play with, to give me options when I started installing,” he says about the new pieces. “Midway, the direction clarified itself, so I decided to finish certain pieces.” The Brant show includes The Swarm (2011), the largest Plexiglas installation Altmejd’s ever done (2.6 x 6.2 x 2.1 metres).

His studio is filled with countless imitation body parts, which are magic ingredients in his baker’s pantry. Plaster ears are laid out on a table, organized in pairs for easy access. Buckets of extra ears sit nearby. “They’re casts of my ears,” Altmejd confides. “Once you make a mould, you can make as many casts as you want.” There are also baskets of fake ants, resin pears, and lots of coconuts. Real coconuts. A little man made of coconuts delivers a jaunty salute. Where does one procure so many coconuts?

“Ask April, she went coconut shopping,” Altmejd quips, referring to the charming assistant with a faint Southern accent who combed New York markets for all the coconuts she could find. Besides their aesthetic qualities, Altmejd likes coconuts because they suggest containment—as do heads.

“I dunno, I’m really into fruits,” he says. “Sometimes I make decisions just because it’s weird and fresh—there’s this idea of freshness or a caricature of the exotic. And there’s this game I have on my iPhone, Fruit Ninja. It’s exotic fruits and you have to slice them. It’s very satisfying.”

Which brings us to the heads. “Oh, the heads are here,” he says, striding off to a table covered with them, mounted on sticks. Zombie-like, they are both creepy and, some may think, seductive, with rocks and minerals peeking out from gaping holes in their skulls. They slightly resemble Altmejd.

One wonders: Are these going to be on bodies? “No, I think these are going to be just stand-alone heads,” he says confidently.

Does he ever do female heads? “Actually, no. That’s really interesting. It’s probably what I am, and also what I’m attracted to, to end up with an object that I find sexy in a way, you know?” The heads aren’t modelled after anyone’s visage, but inspired by the materials from which they are crafted.

Altmejd is obsessed with materials. He frequents an odd little Midtown shop that specializes in minerals. “Usually it’s people who are interested in crystals for their New Age aspect. Not me,” he says. “Very often I go through the store and I try to recognize the shape of a body part in a rock and that can become the start of a piece. The wig store is also a place I go to very often. They say it’s human hair, but it’s not—it costs $15, it’s not human hair.”

Even with the giants, the artistic process is less about the sum of the parts and more about each little piece. “I focus on the microscopic, even if I make gigantic pieces,” he explains. “I make it so big you can focus on each individual part as an end in itself. I’m like the ant that’s not intimidated by us because it doesn’t really see us, it’s focused on the inch by inch. When I work on [a giant] up close, the hole in the thigh can become a world. So it’s an architecture and it’s also a landscape. You know the cliché of seeing chains of mountains and seeing a giant in it, a fallen or sleeping giant—there’s also that mythological aspect. But it’s also what it permits me to do in terms of process: each little area becomes a space where I can have a relationship with material.”

For an observer, the beauty of a sculpture is that it’s different from every angle. Stand somewhere else and the giant acquires another shape, a new meaning. As with life, it’s a question of perspective.

Of course, once in a while he stands back and says, “Oh yeah, it’s a whole.” For an observer, the beauty of a sculpture is that it’s different from every angle. Stand somewhere else and the giant acquires another shape, a new meaning. As with life, it’s a question of perspective. Which might explain Altmejd’s obsession with The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills.

“Oh, I love it,” he says. “I love the drama. I don’t like to live the drama—I’m not very sociable—but I love looking at it. I look at them like they’re birds, you know? It’s the best television I’ve ever seen. What’s amazing is, there’s real reality in that fake reality. They’re having real nervous breakdowns. I seem like a horrible person or like a voyeur, but I can’t stop thinking about it. I think it’s the same as when I was in biology and I observed micro-organisms in a petri dish, or if I’m focused on materials and the way they react together on the giant’s thigh. For me, it’s all as fascinating. I like observing little things moving and reacting unpredictably and trying to understand why they reacted like that, and seeing beauty and drama and horror. Same thing with materials. I like to combine one type of paint and one type of mineral and see flesh come alive.”

This fascination was particularly reflected in his recent plaster sculpture series “Bodybuilders”. “I use plaster casts of my hands as a way of dragging matter from one part of the [sculpture’s] body to another. Usually, these figures are filled with hands and they reshape their body by taking matter from one part of the body and bringing it somewhere else. So some of them have big holes in their abdomens because the hands are taking the matter from the abdomen and dragging it upwards on the head.”

In a similar series called “The Watchers”, angel-like figures sport wings “made from taking the matter—which happens to be plaster—from the body and dragging it upwards to shape wings.”

Altmejd creates unity in space through materials, energy, and contrast, and incorporates many pieces, new and old, into each show. “It’s important for me that an object is able to generate energy,” he says. “The fact that contrast leads to tension, which leads to the production of energy, makes the object function more like a living being. In the giant, for example, I could fill a cavity with ants,” he says pointing to the figure he’s currently working on. “They could actually go down his leg and start travelling in space. I’m not sure yet.”

Mirrors are another obsession. “I like the idea that one object can create two experiences,” says Altmejd. “Objects that are covered in mirror tend to visually disappear. They sort of become invisible, immaterial. It’s a non-physical film. You can’t light it—if you aim a spotlight at a mirror, you’re just reflecting. But then I take a hammer and I smash them and all of a sudden the object becomes real and ultra-physical. Oh my God, I love this idea.”

Considering his vivid inner life, fantastical imagination, and creative connection to mythical archetypes, it’s no shock that Altmejd has been lucid dreaming since his teens. “I’ve never trained myself to lucid dream. It came naturally as a way of getting out of nightmares. I first found out that closing my eyes and counting—inside a nightmare—would wake me up. Then I guess I figured out that if I ever got to the point of closing my eyes and counting, for any reason, I must be dreaming, because I would never do that in real life. So from that point, I was conscious in about half my dreams.” Recently, though, his nocturnal jaunts took an unexpected twist.

“As a teenager, it was all about sex,” he explains. “I’d just look for people to have sex with. Now, I lucid dream less and less, but it happened a year ago, and for the first time I said, ‘I’m not gonna have sex, I’m just going to use this dream to make an experiment. I’m gonna make art to see how it looks, to compare the art in the real world and the art in my dream.’ So I tried to look for a piece of paper and a pencil but I wasn’t able to find one or the other. The next night I lucid dreamed again. I said, ‘I’m gonna do a different experiment now, I’m gonna look at myself in the mirror.’ So I tried to find a mirror, and I found one. I had the courage to actually look at it, in this mirror inside my own head, and I saw myself but in a crazy, exaggerated caricature way. It really gave me goosebumps. So I said, ‘Oh, maybe it’s a funhouse mirror.’ So I looked for another one and I saw the same thing!”

The next day, he did some online investigating and discovered that the consensus is to never look in the mirror while lucid dreaming. “I did and what I saw was horrible.”

That night, he lucid dreamed again. This time, though, he decided to go back to his teenage strategy: sex. “I saw someone and I went up to them and turned that person around, and that person had totally black eyes and was horrible and started scaring me and confronting me and said I am the devil. It’s the first time in my life that I lucid dream and someone is not cooperating. They’re supposed to be zombies—they’re in my head, I’m the master, it’s my territory. Maybe when I looked in the mirror, I opened a door that I shouldn’t have.”

In Altmejd’s wonderland, the intersection of good and evil, of fantasy and reality, of dream and wakefulness, is perhaps the subtle undercurrent of both art and life.

“The most amazing thing about making art is to realize that your work really exists in this world,” he says. “Not just for you, but for other people. I’m sort of a loner and I don’t really feel I exist physically in the world. I don’t feel like I’m in my body—I grew up not being aware that I had one. Doing sculpture was a way of existing physically, not through my body but through a body I would make. Like a kind of avatar. That’s why I want objects to be as intense as possible, to exist intensely in this world.”