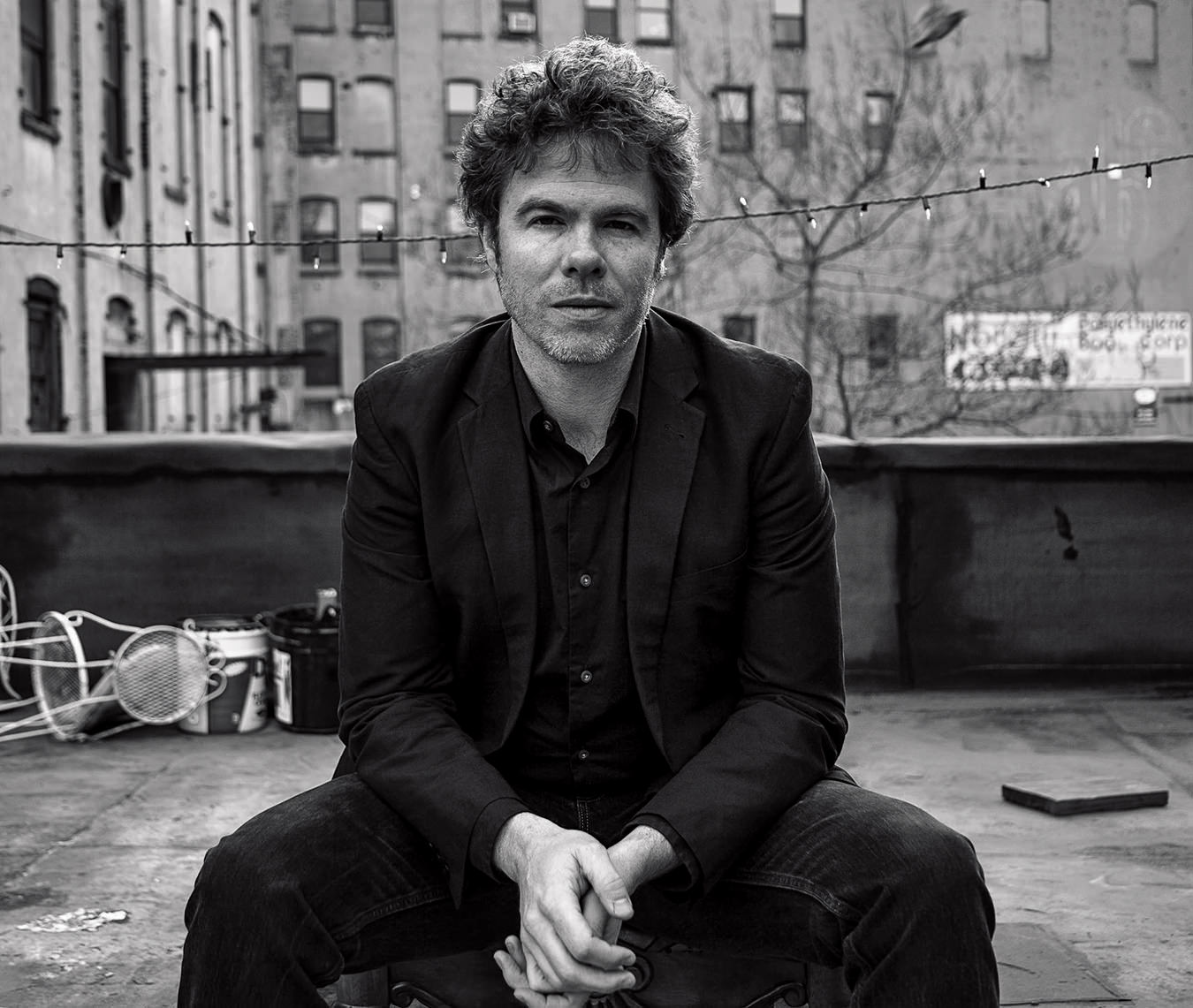

Chris Botti

Top brass.

Chris Botti, jazz trumpeter, looks like the sound he makes.

It’s a Sunday night just before Christmas. Chris Botti is in New York playing the famous Blue Note jazz club in Greenwich Village, as he has every holiday season for the past several years. The second show is about to begin, sold out just like the first, just as all his shows are during this three-week run. His four band members are already on stage when Botti strides in wearing an elegantly tailored dark blue suit, a long black tie, and a white shirt open slightly at the neck. He puts his trumpet to his lips and opens with a meditative but almost blasphemously sensual “Ave Maria”. The audience, crowded elbow-to-elbow in the long, narrow room, is spellbound. The crowd is in love, with the man and with the sound, fused in such startling symmetry.

It is a remarkably young and atypical jazz audience. At my table are a quartet of young professionals and a matronly psychologist from New Jersey. Celebrities abound: actor Gabriel Byrne is here on this night with some beautiful friends. Susan Sarandon was a guest the night before. There is Mami, a woman from Tokyo who came to New York for Botti’s entire three-week run at the Blue Note, and sits at the same table every night. There is a six-year-old boy named Lukas who is studying the trumpet and came with his parents. At the end of the show a woman fanning herself with an autographed Botti CD says to her companion, “Now I can breathe again.”

Along with his other charms, Chris Botti (pronounced boat-tee) turns out to be a naturally personable and engaging show host. He talks to his audience, tells stories, kibitzes with his band mates, recognizes return fans, and comments on the music. Botti manages the show like a maître d’ with a horn. And afterward he is patient and accessible, signing autographs and posing for pictures with a long line of ardent fans.

The next day, over lunch at the casually hip West Village bistro Barbuto, Botti talks about his life and music. He was born October 12, 1962, in Portland, and, apart from two childhood years spent in Italy, he grew up in Corvallis, Oregon. At age nine he started playing the trumpet, and three years later, he says, “two things coincided. I knew I wasn’t going to be Michael Jordan, and I was thinking, well I’m not too bad on the trumpet. And then I heard a recording of Miles Davis playing ‘My Funny Valentine’ and bang, that was it. That really spoke to me.” His mother, a classically trained pianist and teacher, recognized early on that her talented son would need a special teacher. “She conned the principal trumpet of the Oregon Symphony into giving me private lessons at age 15, and drove me the 70 miles to Portland each week,” says Botti. From there he went on to Indiana University’s famous music school, where he studied jazz with David Baker and jazz trumpet with Bill Adam.

In the middle of his senior year at Indiana, while worrying about how he was going to earn enough money to move to New York, he was offered a two-week gig with the Nelson Riddle Orchestra and Frank Sinatra at the Universal Amphitheatre in Los Angeles for a fee of $300. He leaped at this “fantasy trip”, as he calls it, quitting school with his mother’s blessing. Botti recalls, “I arrived in Los Angeles and I got to the first sound check, and Sinatra walks in. The most hilarious part? He introduced himself to the band! Then he called the song ‘Fly Me to the Moon’, and in the middle of it there’s a well-known trumpet solo. I couldn’t play—I mean I was so nervous. I barely got the solo out. And Sinatra at the end of it said, ‘Nice solo, kid,’ because I think he knew I was nervous. And that’s all it took for a kid who had just dropped out of college. I was delusional. Took my fee and headed to New York.” The year was 1985.

At first, Botti “scuffled, playing rap gigs in the worst neighbourhoods, starting at 3 a.m.,” he says. “I looked like Opie driving into the Bronx in my red VW. But just having enough money to pay the landlord at the end of the month was like winning a Grammy. I thought I was on top of the world.”

He’ll play through the tune for the first time slowly, savouring its plaintive optimism, caressing it with his rich, opulent sound but never losing the beat, embellishing the simple tune just enough to make it fresh. Then the trumpet sound bites, and the real jazz soul of Chris Botti emerges.

Lean years though they were, word about Botti got around and he quickly found work in the rich New York jazz world, playing in saxophonist George Coleman’s band and with the Newark trumpet legend Woody Shaw. By day he developed into a highly regarded studio session player. After five years in New York, his first big break came when Paul Simon asked him to join his band, and within the year he played in the famous Central Park concert as part of Simon’s Rhythm of the Saints tour, and he played with Simon for much of the nineties.

In 1999, he joined Sting’s Brand New Day tour as a featured soloist, and the two have remained close ever since. Late in 2001, he made the decision to go out on his own. He made his first recording for Columbia Records that year and since then has added seven more, the latest of which, Chris Botti in Boston, is also a DVD and a celebrated PBS TV special, and was nominated for three Grammy Awards. The success of these records has made him the best-selling jazz instrumentalist today.

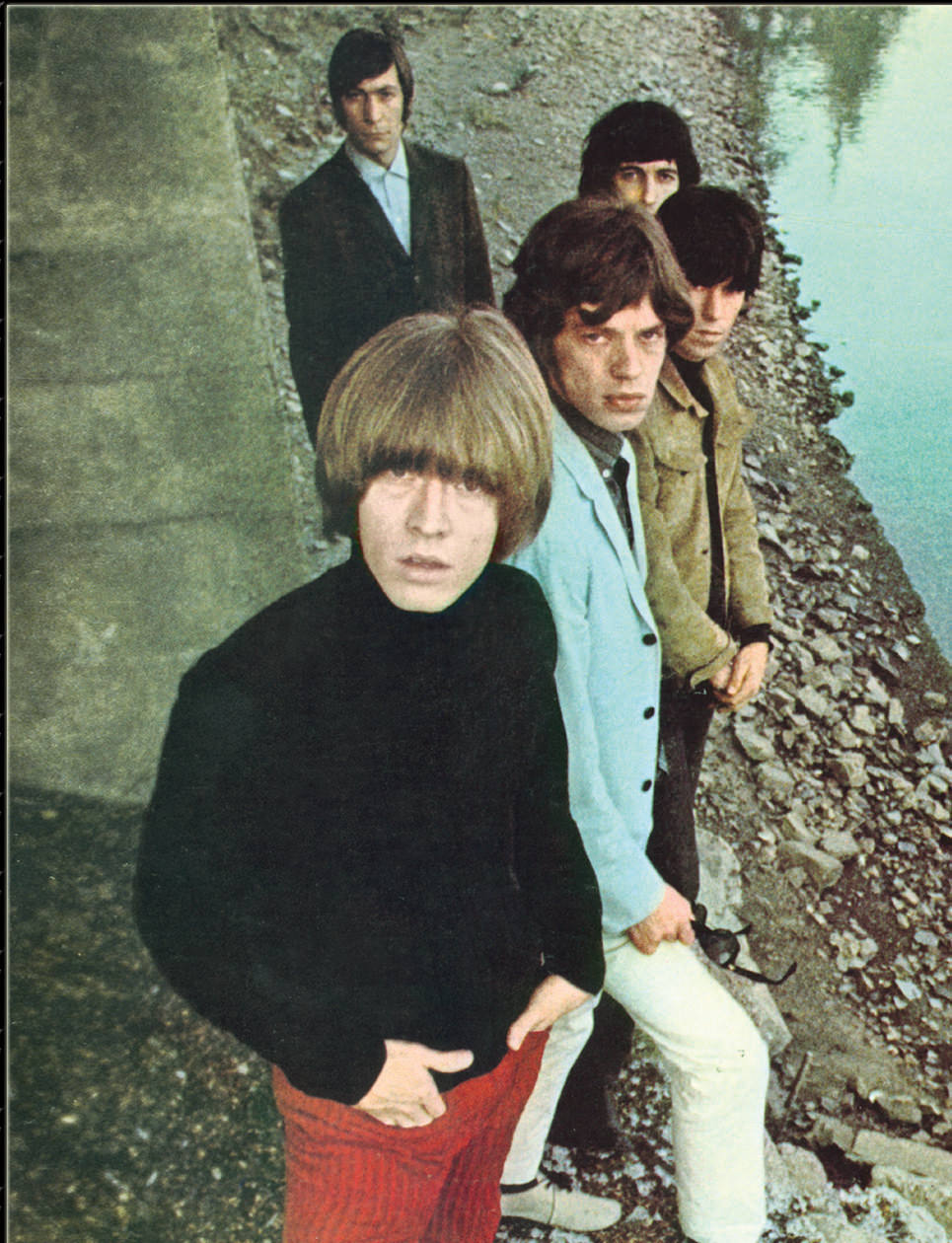

As driven as Botti was in his 20s, he is no less so today at 47. Behind the look and the sound is a man who obsesses about making music his way. His well-travelled trumpet, a vintage 1939 Martin Committee Handcraft, is the same brand that his hero Miles Davis played, as did Chet Baker. The exacting, laser-beam sound of some is not for Botti; he wants that Miles sound, that warm core, that bloom. “It allows me to play melancholy through the instrument,” he says. Melancholy, but cool and elegant at the same time.

His approach is to take a familiar romantic standard, say “When I Fall in Love”, and establish it. He’ll play through the tune for the first time slowly, savouring its plaintive optimism, caressing it with his rich, opulent sound but never losing the beat, embellishing the simple tune just enough to make it fresh. His pianist, Billy Childs, will thread some unusual harmonic colouring in and around the trumpet sound. Maybe they’ll repeat it a second time with some variation. Then the trumpet sound bites, and the real jazz soul of Chris Botti emerges. He hesitates, bends the sound, plays with it, and then takes off with a dazzling array of bebop flourishes reminiscent of the great Dizzy Gillespie.

Unlike many jazz musicians, Botti also obsesses about getting the right sound on his recordings. He talks lovingly about the “space” on Sinatra’s In the Wee Small Hours record, or the “reverberant haze” on Miles Davis’s famous Kind of Blue album. So he selects the best recording studios, the best arrangers, and the best musicians, knowing that this—not a light show or an extra tour bus or an extra assistant on the road—is the key to his success. He is proud of the four band members he’s assembled. (He keeps them busy, he says, so they don’t get stolen away “by crafty, charismatic musicians like my friend Michael Bublé.”)

Whether in concert or in making a recording, Botti is generous in sharing the stage, and here again he takes his cue from the past. “You look at Kind of Blue and you analyze the percentage of time that Miles Davis actually plays trumpet on that album,” he says. “It’s going to be about 18 to 25 per cent. There’s Bill Evans, too, there’s John Coltrane, there’s Cannonball Adderley. You compare that to a Seal album [today]—Seal’s probably singing 75 per cent of the time. I try to forget about my place as a trumpet player and think of me, the listener. What do I want to hear? What would make me feel emotional? That’s what I go for.

“Music in general has unfortunately moved away from Sinatra and Basie, the collaboration between the two of them. Nowadays pop music is just about the guy there and the people in the background with inner ear monitors and they’re playing parts. It’s the same every night. Music has become so rigid.” And so Botti’s band members get part of the spotlight every night, and no two performances of “The Look of Love” or “Indian Summer” are ever the same.

At age 12, says Chris Botti, “I knew I wasn’t going to be Michael Jordan, and I was thinking, well I’m not too bad on the trumpet. And then I heard a recording of Miles Davis playing ‘My Funny Valentine’ and bang, that was it. That really spoke to me.”

He is also known for his collaborations. Chris Botti in Boston features duets with Sting, cellist Yo-Yo Ma, and singers like Josh Groban, John Mayer, and Steven Tyler. For this project, he also got to work with the Boston Pops orchestra and conductor Keith Lockhart. “It ultimately comes down to great casting,” Botti says. “Casting in music is so important, so overlooked, so underrated. Miles was ultimately a great casting director. In pop music, Sting has been a great casting director. That sort of thing is very, very important.”

Like these other “casting directors”, Chris Botti has to be able to play with a wide array of musicians, and he has to believe in their music. His versatility and his comfort level going beyond jazz comes from those early days in New York as an on-call trumpeter for local bands, great pop artists, and recording studio sessions. Long ago he stepped out of the jazz silo and embraced other kinds of music, and adopted Duke Ellington’s philosophy: “If it sounds good, it is good.” Like Yo-Yo Ma in classical music and Sting in pop music, Botti has transcended his genre and has become an artist whose audience is that coveted “we love all kinds of music” group, the closest thing to a general audience that exists today.

Chris Botti is not so much retro as classic. His is a meticulously crafted and sculpted approach to music that looks back to those days when performers obsessed about quality and about doing it their way, and who knew how to dress the part. And, as he’s proving, it never really went out of fashion.

A significant factor in Botti’s success is his constant touring. He plays some 250 to 300 dates a year, which leaves time only for travel between concerts and just a few days off here and there. “Touring is the last great hope for professional musicians,” he says. “What I’m doing is what every jazz musician dreams of—to be able to tour around the world as a jazz act and play for 2,000 or 3,000 people a night. You can’t get any better than that. The music world is littered with guys who had a chance but who screwed it up. I don’t want to be one of those guys. I love it, it’s fantastic.”

But what about having a life? “I’m not great at life. I don’t tour so that I can afford to go chase my life. My life is the tour. When I go home for a life, I’m home for three days and then I’m saying, ‘Let’s go back on the road. Can we please?’ ” What about a relationship? Botti pauses before he answers. “That’s very difficult—very, very difficult. It’s fun if you just want to go have dinner with someone, be superficial, but a couple of times I’ve gone out and it’s been really great, and the woman will be like, ‘You’re coming back when?’ So that’s been really hard.” A few years ago he and CBS News anchor Katie Couric were a celebrity dating couple (“We’re still very good friends. I just saw her last week for dinner”), but now, a committed relationship is just not realistic. “I think a lot of musicians and actors get married and they’re not being honest with who they are or what they want, to have another person share in their life.” He adds, “This is hard for me to say in an interview but I think musicians at the core are selfish. The other person has to know that.”

Until a few months ago, Botti was living out of hotels, his only possessions a suitcase, a yoga mat, and his trumpet. When the seasons changed, he gave away his clothes and bought new ones. Late last year he bought a house in Los Angeles, in the Hollywood Hills—but he still won’t spend more than 10 days there every six months, and he doesn’t see the purchase as changing anything about his peripatetic lifestyle.

And yet he doesn’t see it as onerous. “The only complaint I ever have is lack of sleep,” he says. “In every other way I can’t imagine my life being more fulfilled from what I’ve wanted to do since I was nine years old. I view this point in my life as having the freedom to do anything I want—to have the band I want, the projects I want. I can do any of that now and I’m still healthy enough to tour around the world and gain new fans. What can be better than that?”

Styling by Christopher Campbell for Atelier Management. Grooming by Mateo Ambrose for Warren-Tricomi Artist Management.