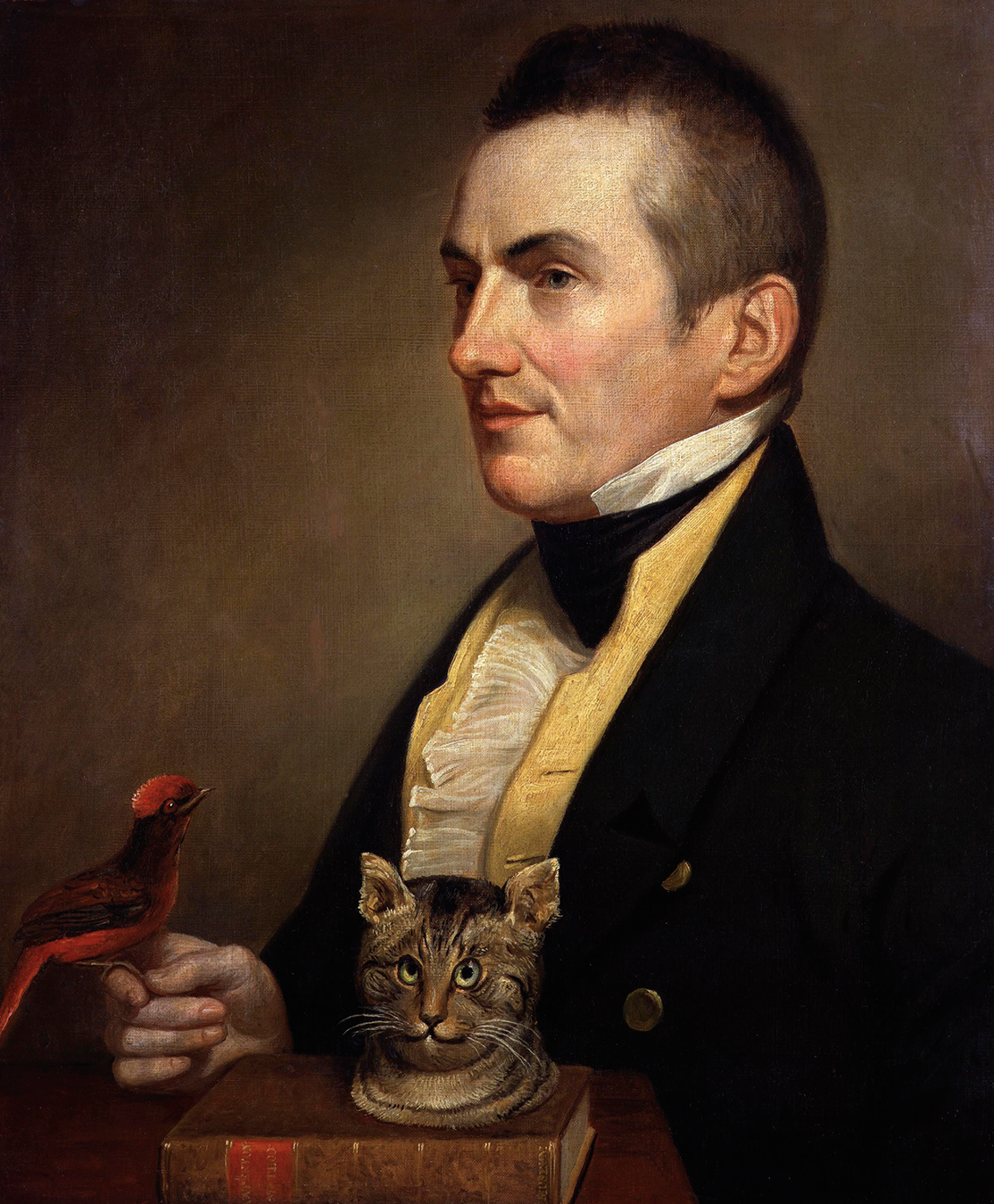

Before the Tiger King, There Was the Rat King: Charles Waterton’s Bizarre Mansion and Game Reserve

A natural oddity.

Charles Waterton only spent a few days in Canada, in 1824, visiting Quebec City, Montreal, and Niagara Falls; although there are lakes and a national park in southern Alberta named after him, he never actually ventured that far. A surveyor named Thomas Blakiston, who respected the great explorers and naturalists of the time and commemorated them with mountain peaks and mountain ranges, did the naming. Officials, however, resented Waterton getting such an honour. He was, after all, a disreputable aristocrat who had wandered South America barefoot, sported a crew cut when such a hairstyle was decidedly not in vogue, was rumoured to bite dinner guests on the ankles, and was given to walking through his mansion on his hands—a mansion in which he spent most of his time not in one of the grand rooms but in a tiny one in the attic, where he kept a preserved baboon hanging from the ceiling and his own clothes hanging over a rope, a room where he slept on the floor with a piece of wood for a pillow. This was a man described as resembling “a spider after a long winter” and, when he spoke, sounding as if he was simultaneously munching on a mouthful of walnuts.

Waterton was eccentric, but he was also much more. His earliest biographer emphasized the oddity of his character and tried to minimize his achievements as a naturalist, and ended up appearing ridiculous because his accomplishments are undeniable. Conversely, a contemporary biographer, striving for seriousness and wishing to concentrate on Waterton’s scientific accomplishments, couldn’t keep her book from being enlivened by his undeniable idiosyncrasies. There was no duality to his nature; there was more to him than just a serious side and a nutty side. Instead, the complexities and contradictions made the man, and rendered him less eccentric than scalawagish.

From his early days, Waterton had an obsessive hatred of the brown rat. This was possibly connected to the story told in those days that when the Protestant King William III of Orange arrived in England to oust the Catholic King James II, his ship was filled with brown rats, which upon landing immediately set to destroying the native black rat population. Waterton’s family had always been Catholic (he was proud to have several saints in his family tree), and while most people took the story as metaphor, he dedicated himself to eradicating brown rats, which he saw as being imbued with the same self-righteous zeal as their Protestant shipmates. He concocted poison potions to kill them, and was seen swinging them by the tail and bashing their heads against trees.

Enrolled at a Catholic boarding school, he was soon expelled for climbing trees to watch birds, and for killing brown rats. At 14, he was sent to Stonyhurst College, a Jesuit school in Lancashire, where the good fathers recognized his talents and made him the official rat catcher.

After his formal schooling, he went to Spain to live with two uncles who had chosen to live in a Catholic country rather than be outcasts, like the black rats, in their native land. He wandered the country observing nature, particularly the quails that migrated from North Africa and the apes of Gibraltar. Waterton learned Spanish, read Cervantes, and became acquainted with Don Quixote, a man after his own heart.

In 1804, he left on his first trip to British Guiana, ostensibly to manage family estates. His jungle wanderings were conducted part-time for the first four years, after which he traversed the country full time for years, returning to England only now and again. He became interested in curare, a poison that the indigenous people of South America used on their arrows. He took different mixtures of it back to England and used them in experiments, in which he would poison animals and revive them by ventilating them with a bellows. He was thwarted in his attempts to try the potions on humans.

Returning to England from British Guiana, Waterton found himself famous because of his wanderings. Rant as he would against the Protestant establishment, he was nevertheless offered a chance to be respectable, to undertake an exploration of Madagascar. He refused, and he would never get another opportunity. Later, he regretted his choice: “My commission was a star of the first magnitude … and the star went down below the horizon to appear no more.”

Waterton spent most of the rest of his life at the family’s 300-acre estate, Walton Hall, in West Yorkshire. On May 18, 1828, Waterton, at the age of 46, married the 17-year-old daughter of a friend from British Guiana. Anne Edmonstone was half Arawak Indian, and had spent the night before her wedding in a convent. She died in childbirth less than a year later, and Waterton, believing himself responsible, never got over his guilt. He brought Anne’s two sisters, Helen and Eliza, from South America, and they remained with the naturalist until his death. They looked after his son, Edmund, and hosted numerous dinner parties during which Waterton would occasionally get up from the table to swing from the doorframes or entertain his guests by acting like a dog and scratching the back of his head with his foot.

There was no duality to Waterton’s nature; there was more to him than just a serious side and a nutty side.

Waterton built a stone fence around his property and turned it into one of the world’s first game reserves. He continued his experiments with curare; perfected a revolutionary method of taxidermy using bichloride of mercury; prepared specimens for museums and private collections, including his own; and, most notably, put together mock animals, often with satirical intent. Typical of the latter was a creature called “John Bull and the National Debt”. It was a porcupine with a tortoise shell and a human-like face surrounded by snakes and lizards. Another, pieced together from the head of an owl, the legs of a bittern, and the wings of a partridge, was called “Noctifer, or the Spirit of the Dark Ages, unknown in England before the Reformation”. But most notorious of his creatures was the “Nondescript”, a creature with an apparently human face that was, in fact, made from the hindquarters of a monkey. Waterton put a photograph of this creature into one of the editions of his most famous book, Wanderings in South America, and many people assumed it was a real animal that he had discovered in the jungle. When the truth got out, Waterton’s reputation as a serious naturalist suffered immensely; he was not unduly disturbed.

Waterton was greatly admired by the famous naturalist Sir Joseph Banks, who in his youth had sailed with Captain Cook and, in his old age, was president of the Royal Society. Waterton’s books were also avidly read by the likes of Charles Dickens and Charles Darwin. But his relations with some of the other famous naturalists of his time were tempestuous, to say the least. He met James Audubon in New York in 1824 and both men hated each other on sight. And Waterton went after Paul du Chaillu, one of the first Europeans to observe a gorilla, calling the French anthropologist’s adventures in Africa “nothing but fables”.

Waterton allowed no shooting on his estate, which he opened up to visitors in the last years of his life. He paid sixpence for every live hedgehog brought to him, built nesting places for birds, and made commodious lairs for foxes. He convinced officials at the local lunatic asylum to allow inmates to come to his property, where he let them wander about and look through his telescopes. The upright citizens of the area deemed this activity proof of Waterton’s own craziness; in our own time, we’d deem it excellent therapy.

Whenever Waterton heard of a freak of nature, be it a two-headed calf or a web-footed cat, he went to see it, or had its body sent to him. Likewise, he’d set off at a moment’s notice to observe unusual human afflictions. Giants and dwarfs were welcomed at Walton Hall, as were those with hydrocephalus.

Forever wandering his property in shabby clothes, Waterton was often mistaken for a particularly unkempt groundskeeper or a recently released convict. In his latter years, he was involved in lawsuits against the owner of a nearby soap manufacturing plant, whom Waterton sued for polluting the water and air for miles around. One suit led to another, and the affair carried on for years, the manufacturer hoping that Waterton would just die. This he did in 1865, after he fell while escorting visitors across his property. He was 83.

Edmund, who evinced absolutely none of the interests or predilections of his father, assumed control of Walton Hall and immediately threw his two aunts off the property. After a couple of seasons of hosting lavish dinners, allowing hunters to massacre the birds and animals, and running up massive debts, he sold the house and land to the offending soap manufacturer.

Portrait from the National Portrait Gallery, London.

________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter here.