At Home With Perfumer Serge Lutens at His Palatial Riad in Marrakech

The fragrance impresario speaks candidly about his life and work.

When Serge Lutens first visited Morocco in 1968, he intended to stay for 10 days. “I needed distance from Europe, from France,” the octgenarian says. “It truly was un autre monde, a different world.”

Geographically, Morocco is close to France, but in feeling, it is far away. It is a sort of refuge. Morocco is where the jagged peaks of the Atlas Mountains bite the blue of the sky; where dust and light meet; where the mélange of smells—spices, wood, flowers—bewitch the air. For Lutens, it is “the place to find the solution to ourselves.”

He stayed for three months. When Lutens did return to France, the desire was stronger than ever to make Morocco home, and in 1974 he set out to find a riad in Marrakech in the heart of the medina. “At the time, the eccentrics lived here. It was enchantment,” he says. Although the riad Lutens fell in love with was in ruins, he thought he could complete the necessary work in a year. Eventually, he purchased enough adjacent riads to create a palatial ode to beauty and artisanship. Nearly half a century later, the restoration is still going on.

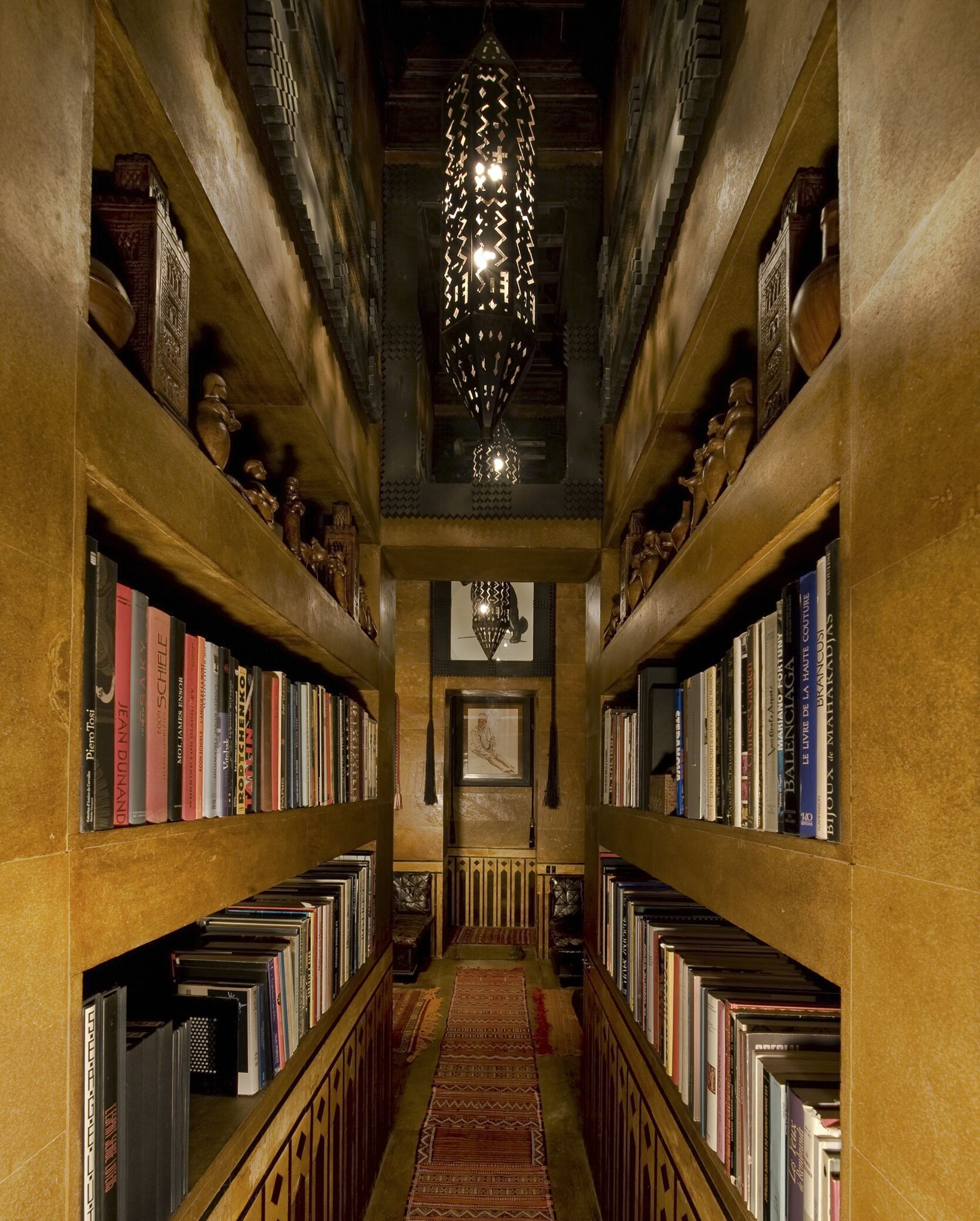

The office library, photo courtesy of the Serge Lutens Foundation.

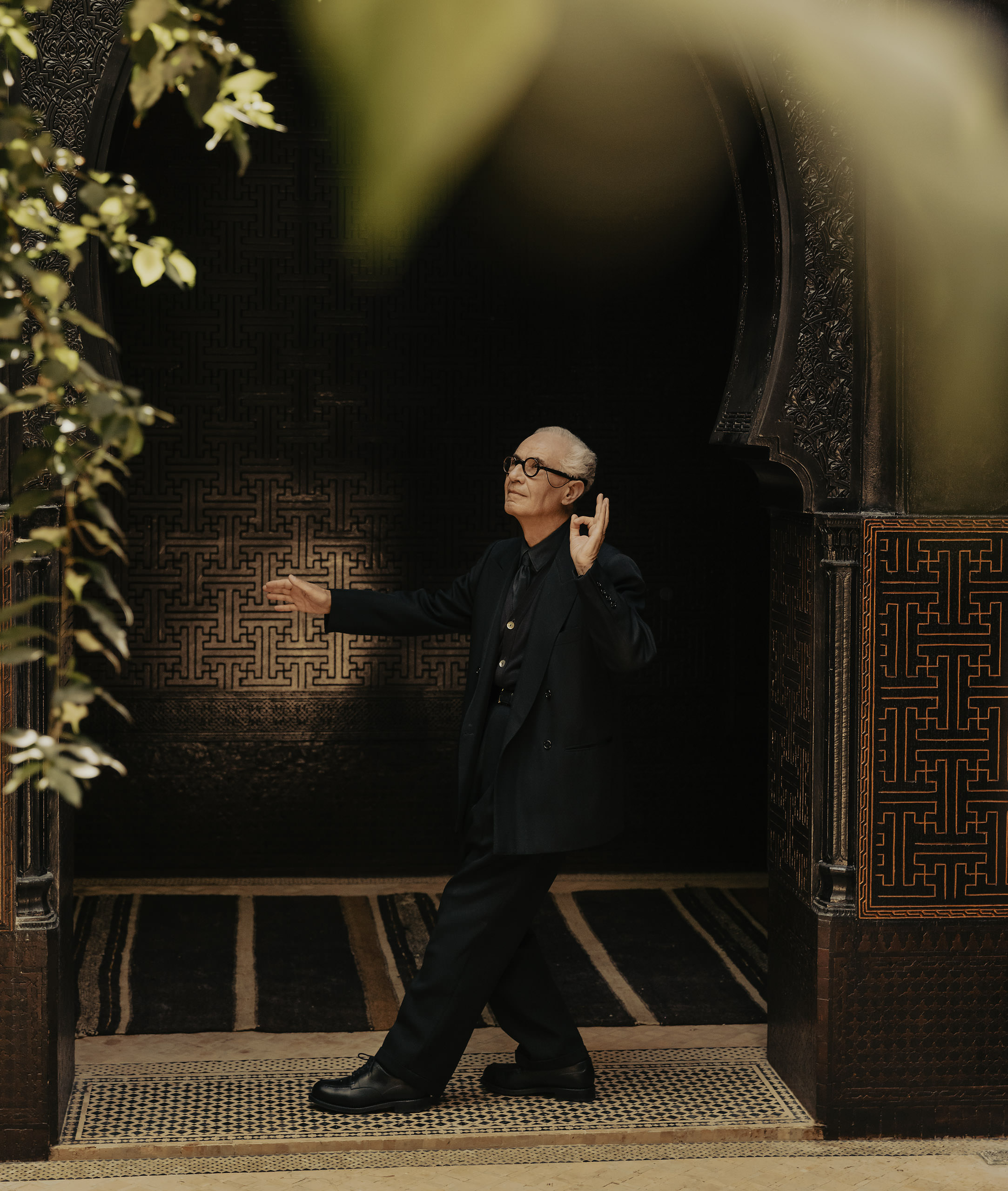

One of the many gardens, photo courtesy of the Serge Lutens Foundation.

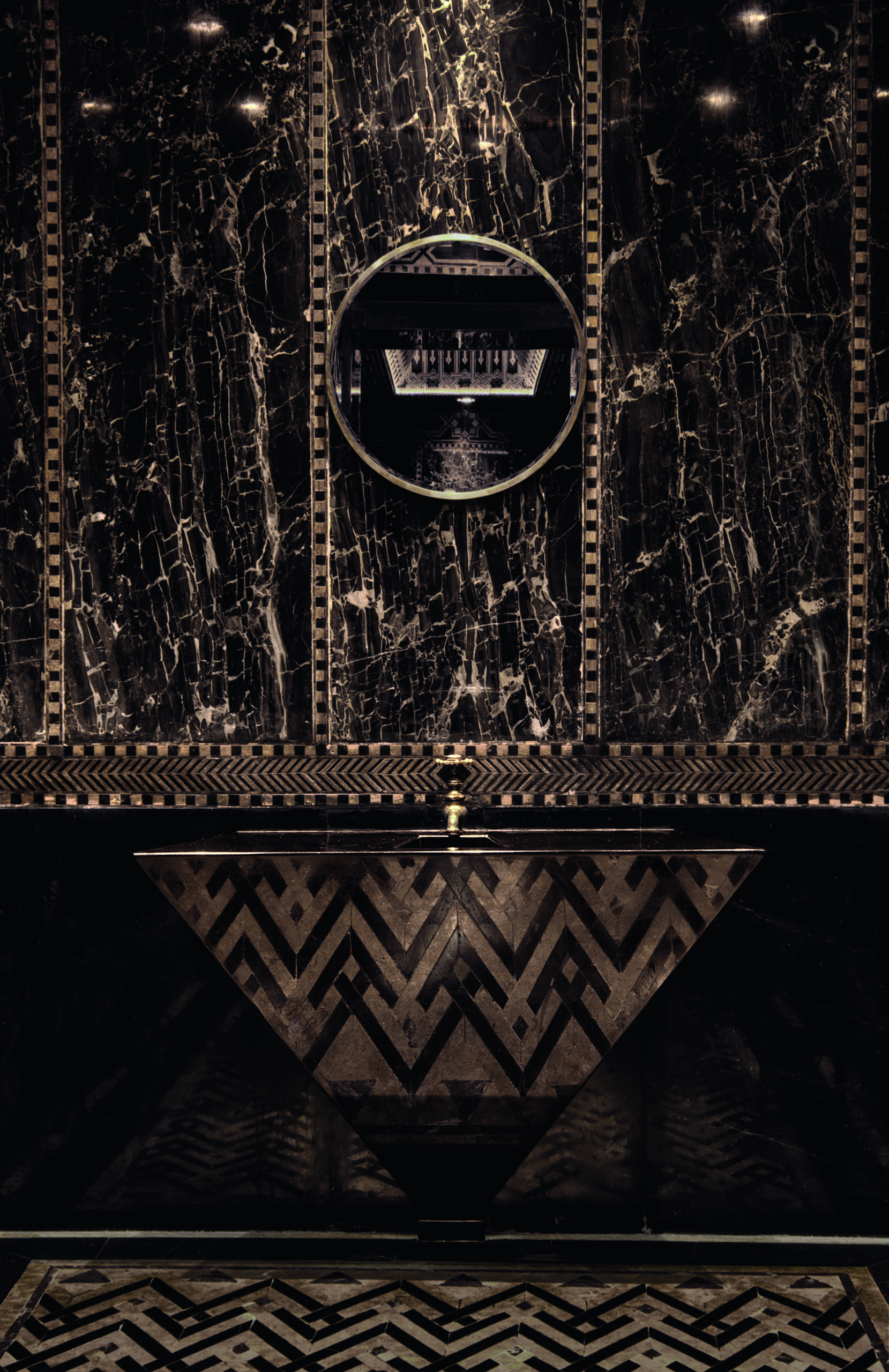

A Sitting Room, photo courtesy of the Serge Lutens Foundation.

Lutens may best be known as the reclusive Frenchman who launched niche perfumery. His boutique in Paris’ Palais Royal has attracted those in search of the extraordinary in fragrance. He was the first to create a unisex fragrance, Féminité du Bois, even though “it was not created as such,” he admits, saying it depends who is wearing it—if rose is worn by a man, it is a fragrance for men and if it is worn by a woman, it is a fragrance for women. “I do not fixate on a person,” he says. “It is not an affair of gender but of taste, of style.”

Lutens, born in Lille in northern France, is artistic in so many ways: makeup artist, photographer, filmmaker, creative director. His first job was at a hair salon, although he admits his dream was to become an actor. He came onto the fashion and beauty radar for his collaborations with Richard Avedon, creating some of the most striking photographs of the ’60s. He thought up the designer makeup line for Christian Dior at the beginning of the 1970s and revamped Shiseido’s image campaigns in the 1980s. He gravitated toward fragrance because “fragrance leads you to memory; memory leads you to words.”

Serge Lutens is artistic in so many ways: makeup artist, photographer, filmmaker, creative director. He gravitated toward fragrance because “fragrance leads you to memory; memory leads you to words.”

The streets of Marrakech are a bustle of activity. Behind an anonymous latticed black wall is a Lewis Carroll–like rabbit hole that engulfs the visitor. This architectural marvel, the Serge Lutens Foundation, is a tribute to Moroccan craftsmanship. Some 500 workers, at times entire families, took turns working on the ceremonial salons of marble and precious wood. Rachid, the major-domo, who has lived onsite for 20 years, points to skylights that had to be encased because drones would hover and take photographs. The maze of a home is a peek inside the mind of a creative genius—the intricate details are dizzying, the rooms increasingly opulent, the smell of wenge from all the wood intoxicating. The sculpted ceilings reach heights of 10 metres, and in one bathroom there is a sunken marble bath that has never been used, but could be. Lutens designed every single detail, from the Moorish patterns on the walls to the filigree of each lamp and the traditional hammam. The house grew without an architect’s plan, almost following instinct. “This is a home that has no end. It is never finished,” Lutens says. “It is not really a home but an obsession.”

Often, Lutens will finish a room only to redesign it. The main courtyard has had three renovations—and it took four years for the geometric carvings of a closet-sized salon to be completed. Lutens’ personal collections include paintings by Jacques Majorelle, Paul Jouve, and Edy Legrand along with one of the largest collections of Berber jewellery and objects that combined are like a cabinet of curiosities brought back from travels. In the library, rare art books reside alongside the complete works of Baudelaire, Proust, and Cocteau.

To an observer, the home seems manic, a suggestion that causes Lutens to pause before saying, “It is very difficult for me to explain. It is a result of my childhood. I was born in 1942, during the war. My mother was an adulterer. I am her son. I am a mistake. I am l’incarnation de la faute.” He is the embodiment of adultery, and this house, in some way, is perhaps a way to repair it. He says it wasn’t his mother’s fault, but the society she lived in. “She was blamed. She was excommunicated.”

___

The architectural marvel that is the Serge Lutens Foundation is a tribute to Moroccan craftmanship. The maze of the home is a peek inside the mind of a creative genius—the intricate details are dizzying, the rooms increasingly opulent, the smell of wenge from all the wood intoxicating.

Beauty is Lutens’ defence to the world, but he says it cannot be defined. “Part of it [beauty] is betrayal. It is something that is not permanent and thus it is a perception.” Serge Lutens the brand has found commercial success while avoiding conspicuous consumption. The perfumer says he is not driven to see Serge Lutens on the labels. What interests him is the process of creating, to continually be doing something. To date he has created around 70 fragrances, and while it takes him a year, on average, to create a fragrance, Chêne and Vetiver Oriental were 15-year processes. “To create a fragrance, we want it to smell good, for it to be personal, on you, on me, with a large quantity of natural ingredients,” he notes.

A Serge Lutens fragrance has the power to transport with a hint of a scent. The perfumes he composes are accompanied by descriptions that give insight into the thought process and composition. For Fleurs d’Oranger: “It’s within us. A single whiff of this fragrance, drawn from the highly scented blossom of the bitter orange tree, augmented by a hint of civet, resonates with us.” Lutens’ first trip to Morocco in 1968 was inextricably influenced by the scent of orange blossom. It was a visual and olfactory shock for this man from the North of France, accustomed to the grey of cities, to watch groups of white-clad women beating orange trees with sticks and gathering the silky and sun-kissed flowers in immaculate sheets. “Unquestionably the scent of happiness!”

And for Ambre Sultan: “This fragrance is not an Oriental, but an Arab and a Lutens. That being the case, don’t expect it to fit in. The point of departure was a scented wax, found in a souk and long forgotten in a wooden box. The amber only became sultanesque after I reworked the composition using cistus, an herb that sticks to the fingers like tar, then added an overtone that nobody had ever dreamed of: vanilla.”

In Canada, La Fille de Berlin is the bestseller (retailers include Holt Renfrew, Saks Fifth Avenue, and select Hudson’s Bay stores). “She’s a rose with thorns, don’t mess with her. She’s a girl who goes to extremes. When she can, she soothes; and when she wants … ! Her fragrance lifts you higher, she rocks and shocks.” The description continues: “A city, a history, an experience… nothing less is required to evoke a woman whose beauty renders her as notorious as her thorny character. Strong willed, explosive—one thing is certain: she will never allow herself to be taken for a ride! … Through a colour, a temperament, and a city, here he paints a portrait of an extraordinary femininity! From a flower to the woman, or a woman to the flower, he hand picks the rose.”

___

The house grew without an architect’s plan, almost following instinct. “This is a home that has no end. It is never finished,” Serge Lutens says. “It is not really a home but an obsession.”

Photo courtesy of the Serge Lutens Foundation.

Perfumer and poet, Lutens considers women to be a force of beauty. “From their beauty I became strong. They are my mirror.” He speaks at length of the beauty of Simonetta Vespucci—“a beauty absolue”—and a portrait of her by Piero di Cosimo that resides in the Musée Condé in Chantilly, France. Vespucci died at 23 of tuberculosis, but “she died beautiful.” (Iris Silver Mist is the fragrance Lutens would have selected for Vespucci.)

The lack of a maternal figure has had a profound effect on Lutens. “Je deteste l’odore du lait,” he says. “Smells are associations.” For Lutens, the smell of milk is unpleasant because of being separated from his mother. He shares his philosophy of scent and memory. Before the age of seven, a child records 550,000 odours. These odours create a path, and when you recognize something, you assess whether you like it or not. “Among the 550,000 smells is a voyage of emotions.” For Lutens, the best smell on Earth “is the smell which we need. It can be the smell of water if one is thirsty.” Perfume is therapy, not a business.

Ironically, Lutens does not wear fragrance. When he started creating perfumes, he wore them a bit, at one point dousing himself in an entire bottle of Cuir Mauresque. But “I feel I am an imposter when I wear a fragrance,” he says. “One cannot make fragrance and wear fragrance.”

Serge Lutens is not driven to see his name on labels. What interests him is the process of creating, to continually be doing something. To date, he has created around 70 fragrances. For Lutens, perfume is therapy, not a business.

The impact of Morocco—the country, its history, its culture—is the source of much of Lutens’ perfume inspiration. Yet Morocco has become something more, this solitary man’s sanctuary and the place where he purposely goes into self-imposed exile. Behind carved cedar doors that overlook a garden of palm trees and cypress trees and bougainvillea is the Serge Lutens laboratory of research and creation and where the archives of the perfumes are housed.

When Lutens settled in Marrakech in the 1970s, “depression had fallen on me like a backlash from my childhood that catches up with you without realizing it.” After much therapy, Lutens is a portrait of a quiet, complex, incredibly talented man with a painful past. He is an inquisitive intellectual with a singular creative vision. “The demons never leave,” he admits. “They are always around. It is important to face the demons.”

Lutens never intended to open his home to the public, but when King Mohammed VI of Morocco unveiled the Royal Mansour, he asked Lutens if visits could be arranged for hotel guests. (Lutens recounts how a Russian visitor once handed him a signed blank cheque for him to write in the purchase price.) As Rachid mentions, every visit is a new experience, no tour ever the same.

Lutens has created this palatial house but has never lived in it, choosing rather to live in a conservative home in the palm grove. “Owning does not interest me,” he says, and he has secured the Serge Lutens Foundation its future as a museum. While “legacies are for kings and gods,” Lutens hopes to leave “un bon souvenir” (a good memory), vowing not to abandon the people who work for him even after he dies. “That is the sense of this foundation. For those that have lived this story with me can continue on living, to keep this in their memory.”

The enigma that is Serge Lutens is to remember that his fragrances are a search for identity—in himself, one he does not always understand.