The artist poses mid-performance in a polka dot outfit by Fiona Curtis of SNAKES (@snakesuits).

Shary Boyle Creates Art That Holds a Mirror to Audiences. What Is There to See?

The stage of self.

_________

Self-consciousness is the enemy of art, Shary Boyle tells me. “It’s always a battle of not letting that creep into your studio,” she says. “Which really is just always having a mirror in front of you.”

Perhaps it’s fitting that I meet the artist over Zoom. My face shares the screen with hers—a slightly pixelated mirror of myself in the top left corner that my eyes dart toward intermittently. I pat down my hair, a movement that recurs subconsciously, as Boyle talks about the layering nature of consciousness. “You are who you are, but then there’s also the you that you’re aware that other people are looking at,” she says, likening the experience to W.E.B Du Bois’ notion of double consciousness. “If that stuff starts to ricochet too much, you’re just endlessly in this double space of confusion and torture because it’s too many ‘you’s, and it’s all judgemental, and they don’t match you as a person.”

The Sculptor, 2019, terracotta, porcelain, china paint, 30 x 28 x 26 cm. Photo: John Jones.

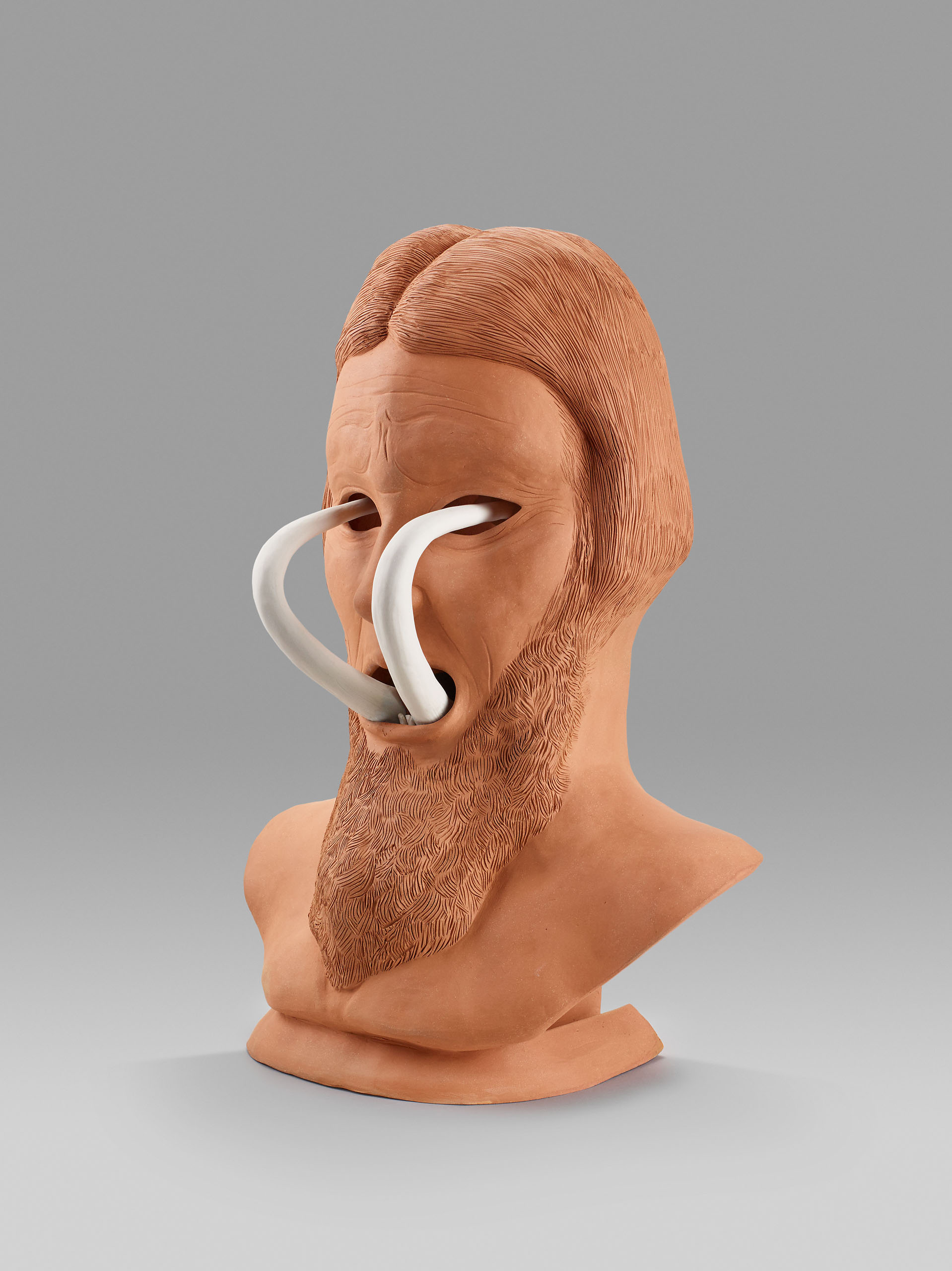

Tusks, 2020, terra cotta, porcelain, glazes, epoxy, 52 x 36 x 24 cm. Photo: John Jones.

Pupils, front and rear view, 2019, porcelain, stoneware, 50 x 41 x 20 cm. Photos: John Jones.

o

Boyle has reckoned with her own reflection throughout her career, responding with visuals, sculptures, and forms drawn from rich mythic worlds and her own imagination. For all its fantastical and almost gruesome qualities—hybrid animal-female forms, faces with tusks curling out of the mouth and into the eyeholes—Boyle’s art is deeply personal. “[Art-making] is how I process life and ideas and philosophy. I work it out through my practice, which is a lot of solitude and reflection and trying to get more and more in touch with myself,” she says. “That’s actually really useful in terms of building confidence as I get older and become more myself.”

Still, Boyle says, it is a continuous battle to create work purely and freely in the face of an unending conveyor belt of eyes, comments, and reviews from outsiders on her works—particularly as a bit of an outsider to the conventions of the art industry.

_________

“We’re always presenting a performance of the self.”

Like a puzzle piece that doesn’t quite fit right, Boyle has always felt a little out of place. The youngest in a large patriarchal family of “aggressive sports men,” Boyle was a highly creative youth—a “weird duckling” as she calls her childhood self. “I just felt so alone so much as a kid. It almost felt like conformity was going to be beyond me,” she says. “And what was saving me and my sense of self was really just my imagination, retreating into it.”

Boyle took to drawing her elaborate inner workings, a form that’s remained the core of her artistry today. “That’s the first language of my imagination,” she says. “If you look at [my craft] like a tree, drawing is the trunk, and then everything else are the limbs coming off.” A multidisciplinary, Boyle often thinks out a piece through drawing, then turns to other mediums: sculpture, painting, live performance, or film.

Grounded in feminist perspectives, Boyle’s art borrows symbols and motifs from mythology and folklore to consider larger universal themes: gender, sexuality, death, youth, injustice. Her work has an uncanny ability to revolt and yet exude a remarkable sense of beauty. A hand lies flat with fingers looped in circles in her 2014 porcelain sculpture Clover Leaf; a bust of a woman’s head gazes morosely in the distance as long strands of black hair grow out of her eyelashes in 2015’s Regret. Bizarre, whimsical, and strangely sexual, her works provoke and disturb, or depending on the audience, comfort and excite.

The Collaboration, 2019, ink, gouache and acrylic on paper, 94 x 108 cm. Photo: Imagefoundry.

Goddess of War, Fear of Death, 2019. Ink, gouache and acrylic on paper. 88 x 105cm.

Perhaps it’s this reputation for oddity that found Boyle invited to partake in this year’s Kaunas Biennial in Lithuania, responding specifically to the world’s oldest museum dedicated to the devil. Filled with folkloric figures and sculptures, the museum and its potential must have felt like a fever dream for Boyle, who stepped away from her usual medium of sculpture by creating and performing in a 10-minute short film, The Trampled Devil,for the biennial. Dressed in elaborate costumes of her own design, she embodies various spirits meant to interact with the sculptures of the museum.

“[The film’s] narrative is around the grey areas between good and evil, because I’m not Christian, and I don’t follow that idea of the devil. It’s a very strange thing in a way to respond to. But I’m very interested in morality and ethics. I can use the archetypes of angels and devils to stand in for our best selves and our worst selves,” she says of the work, which, like much of Boyle’s art, offers a reflection of the viewer’s inner workings.

She studied at Ontario College of Art (now known as OCAD University), first in the experimental department—where she immediately felt crushed by the European and male-dominated standards—before switching to the fine arts department, where things were more open. Still, the experience taught her how judgemental and trend-concerned the art world was. “You have to fight really hard to preserve your own voice, because it’s so easy to get sucked into the kind of crowdsourced idea of what the avant-garde is,” she says. “Which is funny, because you can be incredibly educated and well-travelled and all sorts of things to be a sophisticated person, but if your work isn’t looking like the genre of the moment, you can really be pushed down the ladder.”

Watching some of her peers walk out of master’s programs with a “homogenized voice,” Boyle found alternative ways to expand her oeuvre. “I went through sideways routes to apprentice with either craftspeople, hobbyists, or tradespeople—and that’s been a fascinating way to engage new materials,” she says, explaining how she came to discover porcelain, a significant material in her work, through elderly hobbyists in Seattle. “I heard about a basement class that this 81-year-old woman was hosting on Royal Doulton–style figurines, decorating them and painting them. As soon as I went in and did it, I [discovered] the potentials of this medium and how I could subvert it and take it into a whole new place.”

The scene feels natural for Boyle: sitting in a basement, a newcomer amongst a niche subculture of porcelain-enthralled grandmothers, and working away on forms. Perhaps it’s a penchant inherited from her trades-working family, she wonders, but working with her hands has always felt comfortable. For her, the process of creating is sacred. “Most of the energy of any artwork is in the studio when it’s being made,” she says. “That’s when it’s truly alive.”

Bridging the emotional energy of creating a work with the immediacy of performance, Boyle began to put on live drawing performances through an overhead projector. Using ink on acetate, she draws slowly, with an air of suspense, as a rapt audience follows along. People gasp as the image emerges. These live performances offer a collective interaction with viewers that, as a visual artist, Boyle doesn’t always get to experience. She doesn’t get to see people’s physical reactions to her work that other mediums provoke—the way music evokes dancing, for instance. It’s why she often incorporates sound in her performances as well.

The Sybarites, 2020, porcelain, underglazes, china paint, lustre, 48 x 34 x 34 cm. Photo: John Jones.

_________

Grounded in feminist perspectives, Boyle’s art borrows symbols and motifs from mythology and folklore to consider larger universal themes: gender, sexuality, death, youth, injustice. Her work has an uncanny ability to revolt and yet exude a remarkable sense of beauty.

“I’ve worked with musicians over the years as collaborative partners,” says Boyle, who’s created with Canadian pop icons like Feist and Peaches. “It’s like this third thing that we develop between the two of us, where image and sound meet. And that really cracks open people because we have different parts of our brain that [music and images] trigger, and the combination of both when done well, it just surpasses what either one of them can achieve alone.”

This sentiment is ingrained in her upcoming major solo exhibition next year, Outside the Palace of Me, which has an entire soundtrack created by Boyle to accompany each artwork. The title of the exhibition is drawn from lyrics off a track called “Europe is Lost” by British nonbinary poet and rapper Kae Tempest. “It’s probably the most succinct ballad to the imminent social, political, and environmental apocalypse of the world that I’ve ever heard,” Boyle enthuses of the track. “[Tempest] is such an extraordinary writer, and in that song, there’s a moment where they’re like, ‘Selfies and selfies and selfies, and here’s me outside the palace of me.’ They’re talking about the culture we have of looking at ourselves, looking at each other, looking at ourselves again. Like it’s just becoming this house of mirrors.”

“We’re always presenting a performance of the self,” she continues, mentioning that the exhibition—set to tour to Montreal, Toronto, and Vancouver—will be shaped around metaphors for theatre and performance. The gallery will be built like a theatre stage, she says, and viewers will have to enter through a “backstage dressing room” to emerge on the lit-up stage. All around there will be artworks, including 10-foot-tall pieces, coin-operated works, and motion-sensored animatronics—akin to an old-style amusement park aesthetic.

“I wanted to mix up the audience and the maker,” she says. “I wanted to ask everybody: Who’s performing for who?”

In the era of the selfie, the Zoom meeting interface, the unending stream of self-promotion on social media, what does it mean to really look at oneself? To sift through the many layers of our self-consciousness? I close out of the Zoom window with one last glance at my pixely face and wonder.