Curator Nya Lewis on the Role of the Art Institution in the Aftermath of the Black Lives Matter Protests

Where do we go from here?

In the summer of 2020, the Vancouver Art Gallery was planning an exhibition on Emily Carr and the Group of Seven. It would have been roughly the 17th exhibition featuring Carr’s work in the past decade. But that summer, as the protests following the murder of George Floyd rippled through the world, the VAG set aside the Group of Seven to focus on a new concept along with a written statement of solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement: an exhibition titled Where do we go from here? that acknowledged the VAG’s 90-year history of underrepresenting African diasporic art and artists while looking forward to a more inclusive future.

Common to the thread of corporations and institutions jumping on the trendiness of racial equality following the summer of 2020, initiatives like Where do we go from here? should be scrutinized under a microscope: Is it performative? Is it tokenizing? For Nya Lewis, brought on as a guest curator for the exhibition and notably the first Black curator at the VAG, an exhibition like Where do we go from here? is not enough—and never will be. “I think in that moment for those associate curators to make a decision to reconsider the show that they had been planning and extend the invitation to me was quite brave,” she says.

As an independent curator, Lewis highlights the histories and identities of Black Canadian artists. “Not just a proof of [Black] existence,” she says of her work’s objectives. “But a practice that is really grounded and rooted in Afrocentric themes and ideas.” Lewis is also the founder of BlackArt Gastown, a nonprofit organization that facilitates opportunities between Black artists and public institutions—providing artist mentorship.

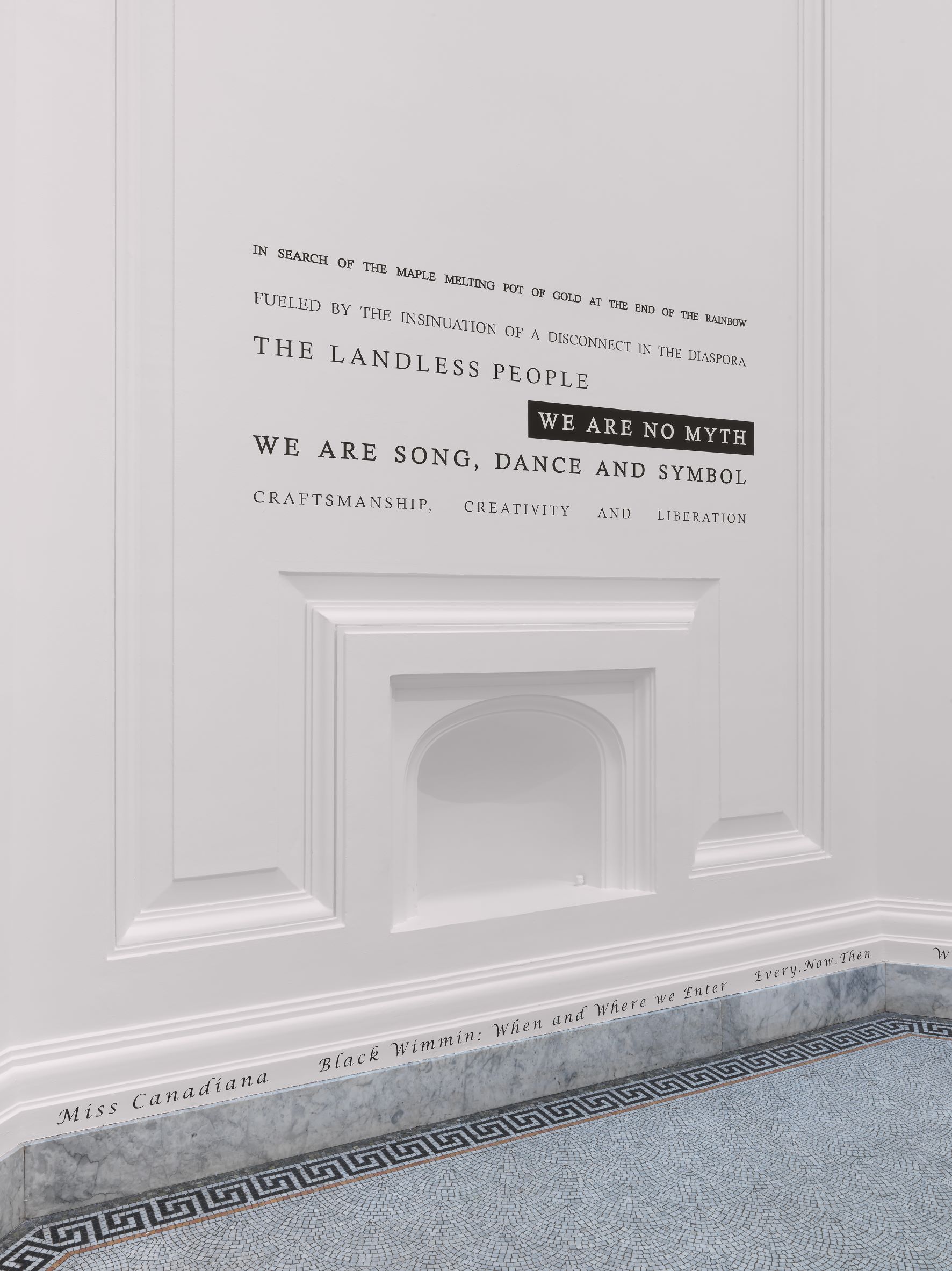

Installation view of Nanyamka (Nya) Lewis, Commit Us to Memory, 2020, in Where do we go from here?, exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery, December 12, 2020 to June 13, 2021. Photo by Ian Lefebvre, Vancouver Art Gallery.

Installation view of Nanyamka (Nya) Lewis, Commit Us to Memory, 2020, in Where do we go from here?, exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery, December 12, 2020 to June 13, 2021. Photo by Ian Lefebvre, Vancouver Art Gallery.

For Lewis, the role of guest curator for Where do we from here? was a request complex in connotation and intention. “I think that they [the VAG] were in a moment where they were being called to task. I think all institutions were being called to think about how they were perpetuating anti-Black racism,” she says. “I felt that tokenism was almost impossible to get around. I was being called into this moment because I was a Black woman curator. But what I also know about being Black in this world is that if I wasn’t absolutely excellent, I wouldn’t have been called. When given the opportunity to shift performative allyship into something meaningful, you do it.”

In her position, Lewis could actively work against the structural inequalities affecting artists of colour in institutional settings. She could—in line with her ethos in general—“shift the way Black production is engaged with, deserving of critical analysis and scholarly discourse,” she says.

“I said yes with very certain terms that Black artists would be up for consideration when acquisition time came around, that the gallery would continue to build sustainable relationships with Black artists, that Black artists would be the centrepiece of the show, and that even though they wanted to include other multicultural voices, it was very clear that this was in response to the murder of George Floyd, and global racial reckoning,” Lewis says.

We Are Not Who We Are Oppressed To Be (Black Speaker, White Walls), Rebecca Bair. Photo by Ian Lefebvre, Vancouver Art Gallery.

Many of the artists featured in Where do we go from here? were exhibiting at the VAG for the first time, including Jessie Addo, Chantal Gibson, Jan Wade, Tafui, and Rebecca Bair. Their work—through mediums of photography, painting, installation, and mixed media—reflects the depth of their individual experiences, and for Lewis, this was important in actively presenting a cohesive collection of Black artists with nuanced and varied identities.

Among the works on display was We Are Not Who We Are Oppressed To Be (Black Speaker, White Walls), an installation piece by Bair. “I asked 10 of my friends to come hang out in a recording studio with me, and we would just chat about our experiences as Black women on Turtle Island,” Bair explains. Ten speakers, facing outward from the circle, each played a different recording. From a distance, the voices melded into each other in a cacophonous arrangement, but closer to a speaker, the individual voice became isolated. At the centre, surrounded by the circle of speakers—who acted as stand-ins for a protective community—hung illuminated photographs of the women, who were purposely blurred. To Bair, the piece, created in 2017, is an exercise in listening and being heard. The installation is not a welcome invitation for dialogue but a space for Black women to speak and share with each other. And in the strength of community, these women can take over physical and auditory space. “We’re going to occupy space and we’re going to make noise and we’re going to make our presence known,” Bair says of the piece. “That’s why I think this work fit in so well with what Nya’s [Lewis] mission was. It’s about reclaiming a sense of presence; it’s about denying all of these other kind of outside factors that are trying to reduce our participation and our presence.”

Where do we go from here? closed this June, a year after George Floyd’s death. A year on from the flood of PR statements, social media posts, and promises to listen from corporations and institutions, how much has changed? In the case of the art institution, the Vancouver Art Gallery has sustained a decent level of inclusive programming. Last summer, the institution partnered with nonprofit Afro Van Connect to support a symposium to provide artistic resources for Black youth. And this summer marked the opening of Soul Power, an exhibition highlighting the art of Jan Wade, who is of African descent. But where is the line drawn between the topical and the foundational when it comes to real change?

“To be very honest, nothing has changed,” Lewis says. “And I say that still with so much hope. There’s an intergenerational approach to the erasure. I think about my mentors and all the other Black women curators that are in their 60s or 70s that have been fighting and have never had the opportunity to curate, how do I bring them into the conversation?”

It’s a sentiment Bair also shares when it comes to making her own art. “I cannot move through this world without giving the props to the Black artists, thinkers, makers who came before us and who paved the way for us to do what we’re doing today,” she says.

The VAG’s solo Wade show is a step in the right direction: as an artist with a 30-year career, Wade is an established and significant voice in the community of Black Canadian artists. This is the first time she has been recognized by the Vancouver Art Gallery; similarly, the work of 77-year-old Jim Adams is being shown for the first time at the VAG in the current Vancouver Special: Disorientations and Echo exhibition, on until early 2022.

Diversity is a word often thrown around with aesthetic connotations, but true equity requires more than representation for representation’s sake. Art institutions have long perpetuated Eurocentric standards, and both Lewis and Bair, as master of fine arts graduates at OCAD and Emily Carr respectively, experienced the colonial values that continue to shape the ecosystem of art in the Western world. “Both of us have struggled to find Black teachers and mentors; both of us have struggled to have Black art be represented in the curriculum,” Lewis says.

Diversity is a word often thrown around with aesthetic connotations, but true equity requires more than representation for representation’s sake

Following last summer’s BLM protests, art became an important vessel for messaging. But what does it mean when that art is being commissioned by the power structures built on colonial values? The transitory nature placed upon Black art also calls into question the role of exhibitions like Where do we go from here? While the voices and minds behind the scenes, at the head of the table, or in the boardroom have remained the same for the past 25 years, how much meaningful change can really be enacted? For Lewis and for Bair, it’s more than having exhibitions centred on Black artists, and it’s much more than hiring guest curators of colour.

Installation view of Where do we go from here?, exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery, December 12, 2020 to June 13, 2021. Photo by Ian Lefebvre, Vancouver Art Gallery.

“It is still very performative in the sense that we are talking about giving [Black] folks shows, and we’re not talking about hiring on Black curators. We’re still taking the position that Black creators and academics are guests in the space. What does that mean for the artists of colour that we are constantly in a position to be guests? Which means that we’re constantly in conflict or in an interrupted conversation,” Lewis says. “The real institutional change has yet to happen. The exhibits are wonderful, and we want those to continue. But what we actually want is a conversation and then action about how we can restructure.”

But the art institution is no longer the sole place for underrepresented artists to reach public audiences. And while institutional structures continue to be challenged, spaces specifically carved out for Black and/or Indigenous artists can foster community while providing vital resources: spaces like BlackArt Gastown or the Black Arts Centre (BLAC), of which Bair is a director. BLAC is a Black-youth-owned facility operating as a gallery, studio, and communal gathering point in Surrey. Set to open later this year, the centre will offer workshops, exhibitions, performances, and mentor opportunities for BIPOC artists of all ages.

“We’re doing the work to really connect with the community and understand what the Black community needs as a space to show art, and no other institution is really doing that,” Bair says. “BLAC is supposed to revolutionize this idea of a space where art goes up, because the community wants to put art up, where it’s used for community gatherings, for education, for mentorship.”

“We are not going to replace 90-year-old institutions in a year,” Lewis says. “But what we can do and will do is take what we have skill-wise as facilitators, as educators, as curators, and create our own spaces.”

When it comes to the historical blind spots of art institutions in recognizing Black art, the answer is not to just look toward more inclusive futures. It is to shift the current foundational perspectives while honouring the overlooked perspectives. “Back to the start is where do we go from here,” Lewis says. “Right back to the start, gather everyone that we strategically left out, and keep going to reimagine a future for Black cultural production.”