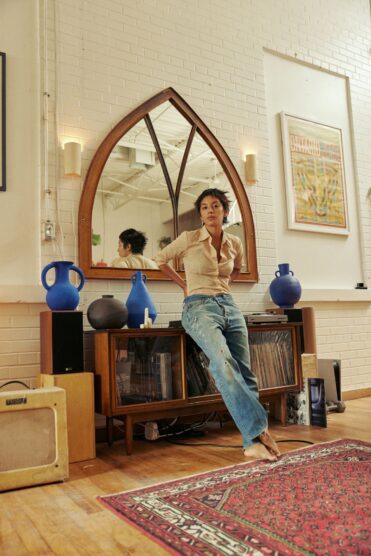

Tamara “Solem” Al-Issa Dives Below the Surface With Her Ceramics

The Syrian-Filipina sculptor based in Toronto hand-builds ceramics inspired by her multicultural roots and tradition.

Photo by Kayla Rocca

For Toronto-based sculptor Tamara “Solem” Al-Issa, ceramics started as an escape. “I was studying at the University of Toronto and working as a human anatomy teaching assistant, so my life revolved around biomedical science,” she says. “I needed to break up my schedule, and pottery is what I chose as my relief.”

After some introductory ceramics practice at the Gardiner Museum in Toronto, she found an artist mentor who let Al-Issa practise out of her studio on weekends. “I never thought I would take up pottery as a career,” says Al-Issa, who was born in Jeddah and grew up in Saudi Arabia. While it was initially only meant to be a hobby and a creative release, ceramics soon took hold of Al-Issa’s heart and mind, and by the time she graduated in 2019, she was ready to dive in, opening her first pottery studio in early 2020.

From the beginning, Al-Issa’s attraction to ceramics has been more than surface level. “I’ve always been interested in the anthropological side of pottery and how it historically tells such detailed stories about civilization,” she says. The primordial nature of ceramics and its history find form in Al-Issa’s vessels, which often give subtle reference to the traditional styles and shapes of her family’s roots in Syria and the Philippines.

Photo by Kayla Rocca

Photo by Kayla Rocca

More than the cultural resonance, Al-Issa finds that the act of throwing pottery on the wheel and hand-building larger clay forms and vessels connect to something deeply personal. “I love how hands-on this craft is,” she says. “You barely have to think when you practise—your body becomes your mind.”

Although she started out throwing clay on a potter’s wheel, eventually Al-Issa scaled up her sculptures and turned to hand-building. “I coil and slab build my vases,” she says, referring to the technique of rolling out clay into thin ropes and winding and stacking them around one another to create a hollow vessel. Rather than shaping the vessel out of a solid block of clay on a spinning potter’s wheel, hand-building allows for more organic shapes, a larger scale, and more evidence of the artist’s hand.

“It usually takes a few days to hand-build a vase, and another two to three weeks to paint, fire, glaze, and fire them again,” says the artist, who uses a custom blue underglaze recipe to achieve her signature ultramarine Yves Klein-esque blue. “After the initial bisque fire, I glaze the interior, then fire again at a slightly lower temperature than my clay requires, which keeps the surface velvety.”

Photo by Mattea Marrese

Photo by Tamara “Solem” Al-Issa

These days, Al-Issa is experimenting with larger sculptural forms like light fixtures and concreting structures and is honing her craft to achieve more consistency with her work. “There are some variables you can’t control with ceramics, though, so I hope to go easier on myself at the same time,” she says, referring to the reason she started experimenting with ceramics in the first place.

___

“Making ceramics has always been a meditative tool for me.”

As she prepares to present her work at the Scope Design Fair at Art Basel Miami in December, Al-Issa is also developing a new collection of sconce light fixtures and working on some new collaborations that are still under wraps. No matter the outlet, it’s clear that for Al-Issa, ceramics will always be a profoundly personal endeavour. “Years ago, my goals were based in achieving some sort of esteem and to prove to myself I could become good at ceramics,” she reflects. “Now, I mostly crave the freedom to create and share and learn.”

Photo by Kayla Rocca